- Nasikin, photo: Tom Nicholson

- Tom Nicholson, “I was born in Indonesia”, photo: Christian Capurro

- Tom Nicholson, “I was born in Indonesia”, photo: Christian Capurro

- Tom Nicholson, “I was born in Indonesia”, photo: Christian Capurro

- Tom Nicholson, “I was born in Indonesia”, photo: Christian Capurro

- Tom Nicholson, “I was born in Indonesia”, photo: Christian Capurro

- Tom Nicholson, “I was born in Indonesia”, photo: Christian Capurro

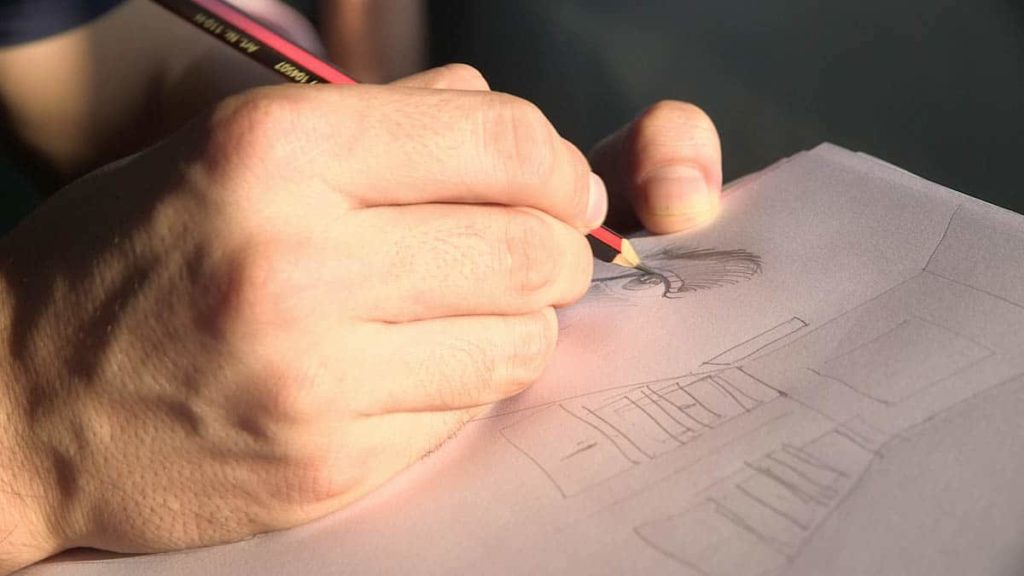

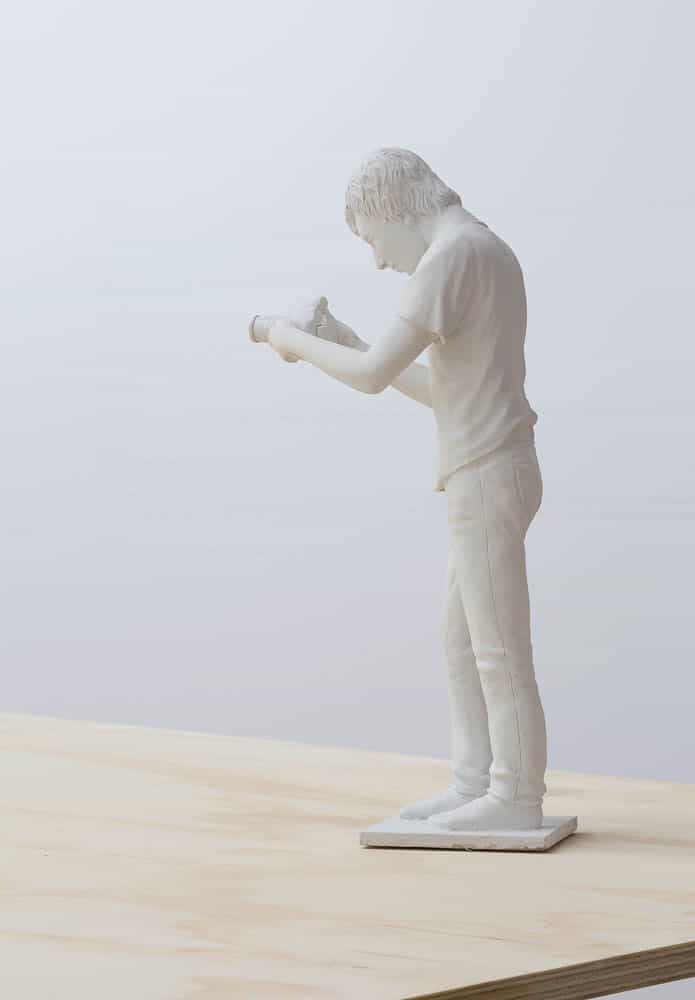

Tom Nicholson’s exhibition I was born in Indonesia engages with the material practice of history-making through dioramas. Nicholson approached Art Merdeka Studio to make figures based on drawings he made derived from interviews with Hazara refugees currently living in Cisarua, near Bogor, Java. As Nuraini Juliastuti observes, this form of monument opens up new stories beyond the official history.

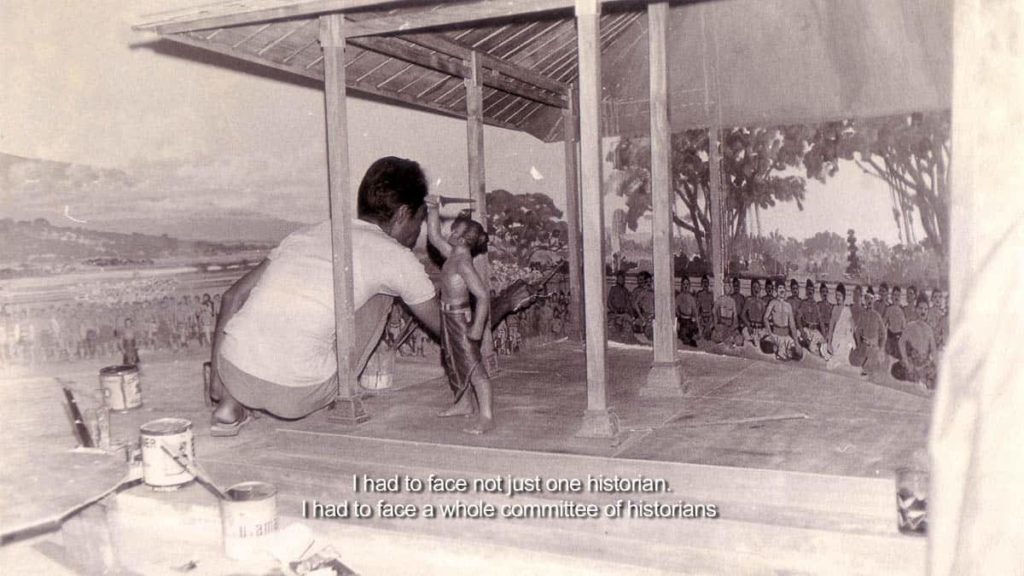

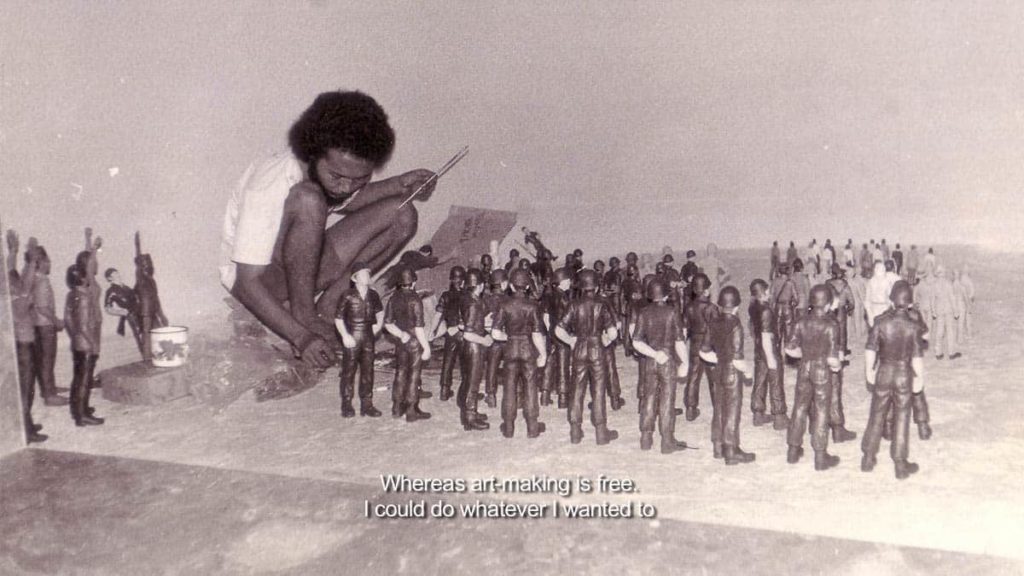

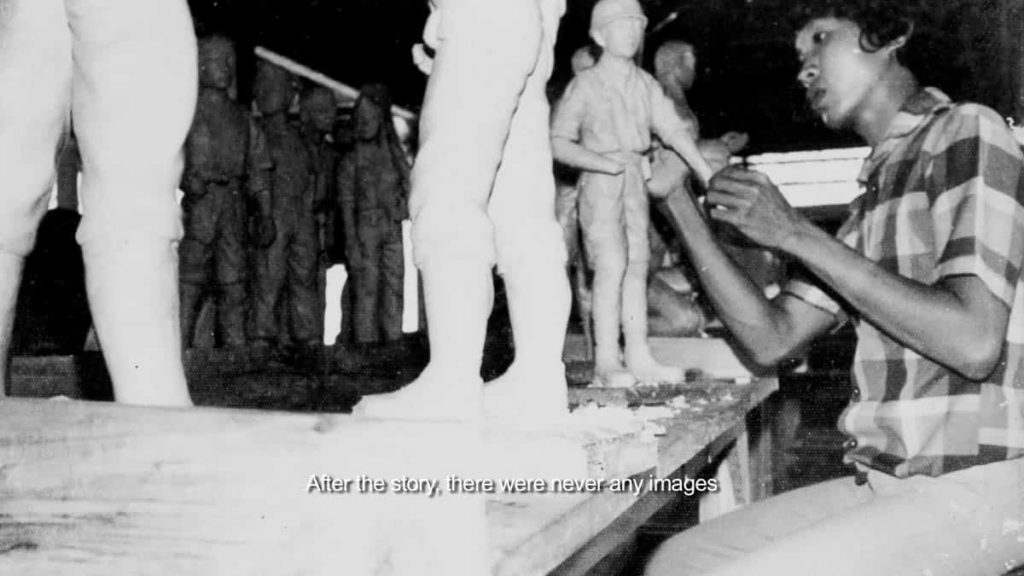

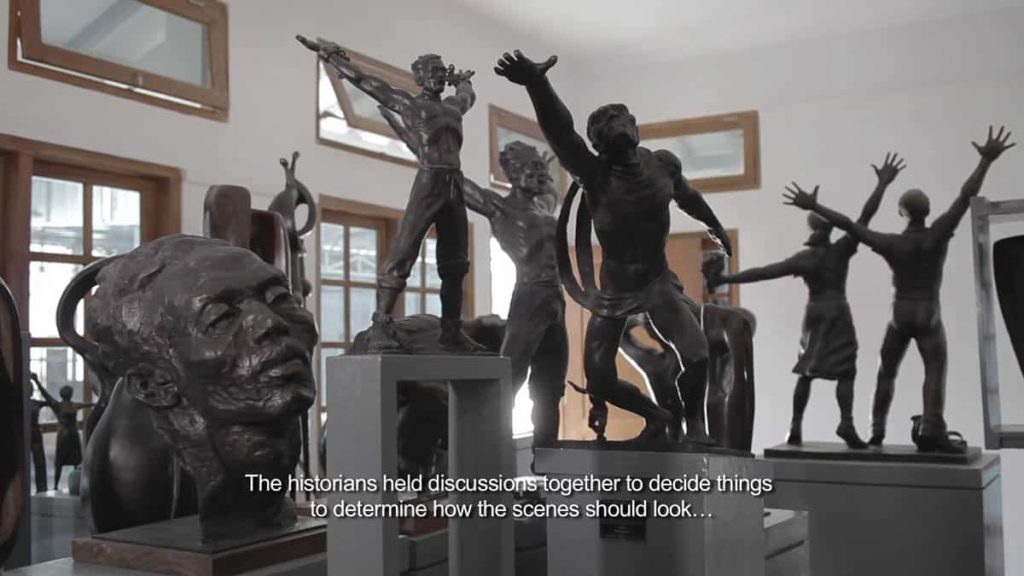

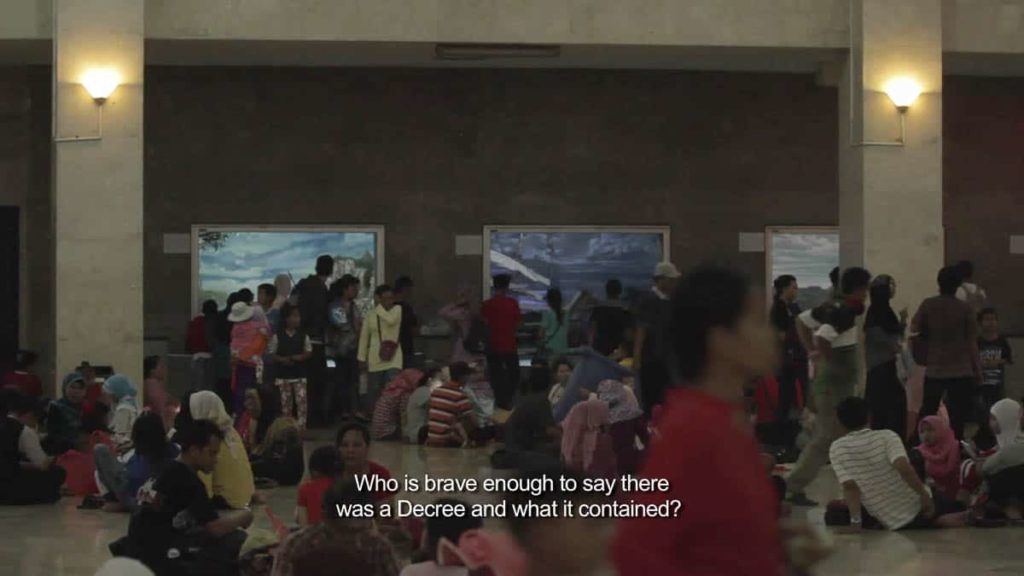

There were three ways to enter the exhibition rooms containing Nicholson’s work, I was born in Indonesia, which was exhibited at the Ian Potter Museum of Arts, Melbourne. The first way led me through a wide big table with a diorama to chronicle a series of personal events of the Hazara refugees in Cisarua. Tom Nicholson made drawings based on interviews with the refugee community that informed the diorama made by Art Merdeka studio in Yogyakarta. The second way led me through the room with a video work, made as a collaboration between Nicholson and Grace Samboh, to record an interview with Edhi Sunarso—a prominent Indonesian artist and an important figure behind the diorama making in the Monumen Nasional, or Monas, as it is usually called. The third way led to a room where single video channels were installed on the walls. They showed interviews with the Hazaras in Cisarua. My knowledge of Cisarua and the Hazara community is facilitated by the information made available for public (Nicholson’s work being the one).

But I have long been familiar with the diorama. The familiarity stems from its systematic use in the state-established monuments. It is systematic because diorama installation is one of the official tools to narrate the national history. Dioramas are about which version of the history that would likely to be put at the forefront. They are about the stories that the state would like to be heard by the people. Visiting these monuments is like re-reading the history textbooks in school.

The diorama production involves a collaboration process. Its construction requires the works of a collective. The interview with Sunarso provides insights into how the collaboration in the diorama making operates. The kind of collaboration to occur in the diorama production in Monas, for example, has a strong hierarchical feature. While Sunarso was assigned as the production chief and teamed up with a group of artists to produce dioramas of Monas, he had to take advice from a group of historians who reported directly to the president. When the country was in political turmoil in 1965, the position of the president as the highest authority in the hierarchical system was also changed.

There are two things from the diorama of the Hazaras in the first room, which marks the difference from the diorama in Monas. First, the diorama makes visible and audible the stories of the refugees. It reveals stories, which would otherwise stay hidden. Such visibility is important because the stories are still underrepresented in the local context. Second, in the diorama production process, the meaning of making histories is redefined. As refugees whose stories were told in the diorama, the Hazaras also took an important role in the production process.

In Nicholson’s work, the Hazaras’ diorama is juxtaposed with the story of Monas’ diorama. It represents different logics of diorama making (and history-making). The stories contained in Monas’ diorama seem always certain, though the interview with Sunarso makes clear that there are holes in what seems to be fixed in the narration of the national history (how to represent the story of the West Papua, and how to depict the Supersemar document?). But there is no room for remaking in the diorama staged in the state museums or monuments. The Hazara diorama, on the other hand, is made based on the stories that are mined from conversations. Along with the character of the conversation that is flowing, it allows a remake of the diorama.

***

To be in a faraway place from the homeland means to depend on the generosity of the others. The organisation of the Cisarua Refugee Learning Centre (CLRC) is such an example. The day-to-day management of the school is partly based on the kindness of and collaboration with volunteers, donors, alumni, and the community who live in the environment. It is also partly based on the resilience of the refugee group, which attempt at working and living well in a foreign land. In the middle of uncertainties, there is a certainty that to keep it going is a must. Children must continue their education. Adults must get on with the everyday.

In the local context, there is another type of generosity, which translated into readiness for contributing labour to fulfil a certain goal. To activate generosity is to build a form of cooperation that locally known as “gotong royong”. The Hazara community in Cisarua helps and coordinates with each other to organise their lives—from running the community school, arranging Eid or Spring festivals, to just being together during the times of uncertainty.

What does it mean to perform cooperation and different forms of collaboration in an environment where gotong royong exists? During New Order era, gotong royong was perceived as an important principle to mobilise free labour of the people to orchestrate the state agenda. On a smaller scale, gotong royong has been regarded as a mechanism to demand voluntary support from the community to accomplish a shared need. The tone of participation in gotong royong practices always feels like a moral obligation. It feels as such because the drive to participate is often imposed on the people by different forms of institutions to regulate the relation between individuals, state, and environment. Gotong royong was usually accompanied with a check-in mechanism to ensure the presence of the family representatives in the neighbourhood.

The kind of gotong royong practiced by the Hazara community is a self-organised act. It does not mean that there are not many examples to demonstrate gotong royong as part of independent initiative to achieve a collective goal. The refugees had been trained in utilising various connections and establishing new ones in order to survive. A series of interviews in Nicholson’s work reveals that generosity is experienced as something intertwined with uncertainties. The collective goals of the Hazara community are always shaped and informed in relation with the unknown course of their life journey. Inherent in their self-organising act of collaboration is the willingness to gamble on its productivity.

The Cisaruans and the Hazaras were strangers to each other. Even among the Hazaras, many of them only knew each other when they were already in Cisarua. They did not have experience of cooperation in the past. There was not enough baggage for this kind of capital to work together. From the Cisaruan’s perspective, the Hazaras were regarded as pendatang, visitors. The Hazaras too thought of their position in Cisarua as part of their unknown journey. Cisarua was the unknown land that evolved to be something that they would love and miss, when they have relocated somewhere else.

Here the Hazaras can be regarded as a group of people who are currently numpang in Cisarua. Numpang is a colloquial term in Indonesian to refer to a condition where the existence of someone or something depends on the existence of the others. Along with the passing of time, though a foreign place could grow to become home for those who are practising numpang, they would usually still be seen as visitors. There are clear lines to delineate the ownership position between those who are regarded as the real owners of the house and the rest who come later as the visitors.

The locals of Cisarua become neighbours, and perhaps some of them become real friends. They open their houses to be rented by the refugee community. Various warung, street-side food stalls and shops, in the neighbourhood, become the regular places to eat and shop the groceries for the Hazaras. People, streets, buildings, and other spaces, become a new infrastructure in the everyday life of the refugees.

The exhibition opens up questions which it cannot answer and will only be answered over time. How would the Cisarua community perceive the refugees? Are they still regarded as mere visitors from a foreign land, or part of the extended family? What aspects that would make sharing sustainable? Is the intention to share mutual? Would this coexistence lead to more fruitful collaboration or develop into friction in future? However, through retelling the memories as well as the dreams and aspirations of the refugees, Nicholson’s work evokes new narratives on how the history is made and remade. Within the established context of diorama making in Indonesia, cooperation is a tool to establish certain views on history. In Nicholson’s work, the diorama is appropriated as a metaphor to say that cooperation is a useful tool to counter uncertainties, regain a sense of agency, and reset the course of history.

Author

Nuraini Juliastuti is a co-founder and member of Yogyakarta-based KUNCI Cultural Studies Center. Her research focus is situated in between arts, alternative cultural production, and media culture.

Nuraini Juliastuti is a co-founder and member of Yogyakarta-based KUNCI Cultural Studies Center. Her research focus is situated in between arts, alternative cultural production, and media culture.