- Todd Couper, Toi Mauri – A Rising Force, 2014, Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

- Todd Couper, Spirit of the Boar, 2013, Private collection, USA. Photo: Courtesy of Spirit Wrestler Gallery.

- Todd Couper, Toi Mauri – A Rising Force, 2014, Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

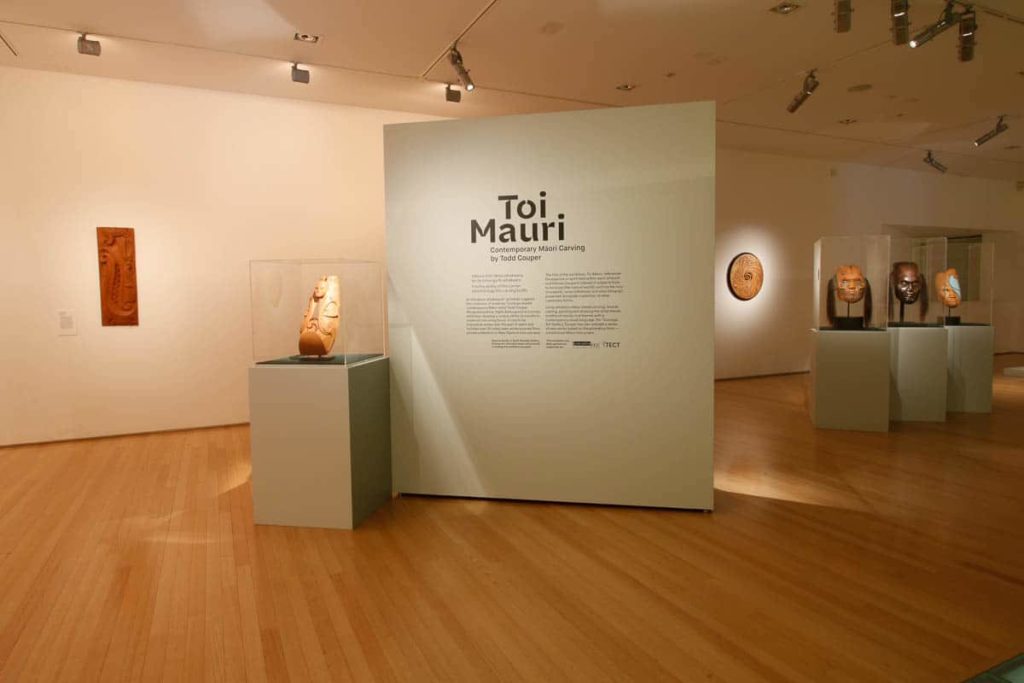

- Todd Couper: Toi Mauri (exhibition installation). Photo: Tauranga Art Gallery

- Todd Couper: Toi Mauri (exhibition installation). Photo: Sam Hartnett

- Todd Couper, Whanau, 2016. Photo: Courtesy of Anne Thrupp.

E rua tau ruru

E rua tau wehe

E rua tau mutu

E rua tau kai

Two years of wind and storm

Two years of when food is scarce

Two years of when crops fail

Two years of abundant food

This whakataukī suggests that prosperity comes with patience and perseverance, a notion that is perfectly reflected in Todd Couper’s carving practice. His careful planning and expert execution have resulted in a carving style that is assured, but also requires a significant dedication of time and attention to detail.

My first introduction to Couper’s work was when I was invited by Eugene Kara to co-curate an exhibition of whakairo rākau (Māori carving). The exhibition was called Matatoki: Contemporary Māori Carving (2014) and brought together graduates from the Rotorua based carving schools at Waiariki Institute of Technology and the New Zealand Māori Arts & Crafts Institute. One of the catalysts for this project was that many of the works produced by these now established carvers were going directly offshore, predominantly to private collections in the United States and Canada. Couper, who had begun his career working with Roi Toia, another talented carver, was quickly picked up by Vancouver based Nigel Reading of Spirit Wrestler Gallery who recognised the young carver’s significant potential.

Following the success of Matatoki: Contemporary Māori Carving I moved institutions and invited Couper to have what would become his first solo exhibition in Aotearoa after over 20 years of exhibiting internationally. The exhibition entitled Toi Mauri: Contemporary Māori Carving by Todd Couper (2017) held at Tauranga Art Gallery allowed Couper to move in fresh, innovative directions creating new works that investigate unexplored territory for the artist in relation to technique, form and subject. As part of the exhibition, Couper envisioned a related series of works inspired by the traditional Māori taonga puoro (instrument) known most commonly as the pūrerehua (bullroarer). He was interested in teasing out a range of ideas using the same basic form, “I wanted to investigate a wall-based 2-dimensional form and experiment with ways to create depth and build narratives using paint, layering, texture and pattern”. With this body of five works Couper has pushed the physical and dimensional parameters, but he also wanted to discover where he could go with the subject conceptually.

- Todd Couper, Purerehua series #3, 2017. Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

- Todd Couper, Purerehua series #1, 2017. Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

- Todd Couper, Purerehua series #4, 2017. Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

- Todd Couper, Purerehua series #2, 2017. Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

- Todd Couper, Purerehua series #5, 2017. Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

A traditional pūrerehua (also known as rangorango, turorohu, whēorooro, huhū, and hamumu-ira-karaka) consists of a thin, flat piece of hard material, most commonly a resonant wood such as matai (Podocarpus spicatus), or sometimes whalebone and stone. This elongated oval that resembles the end of a hoe (paddle) is attached via a muka (flax fibre) or harakeke (flax) cord to a decorated rod. The user swings the taonga puoro in increasingly swift rotations about their head, creating a deep whirring sound that is sometimes accompanied by a series of low booms. Other examples of pūrerehua are simply connected to a long harakeke rope and swung directly by the user. Utilised in a variety of ways over generations, this instrument is most closely connected with the arts of the tohunga (priest) who used his considerable skills to call on the power of the atua (gods).

In te reo Māori, a single word can also hold power and may suggest a multitude of layered meanings and knowledge. It is often not a physical description, but rather suggests a variety of relational contexts that may be metaphorical in nature. For example, pūrerehua is also the name for a bag moth (Liothula omnivora), suggesting comparisons between the insect’s loud, ruffling wingbeat and the low whirring noise of the taonga puoro.

Another name for the pūrerehua is rangorango, which is what some iwi (tribes) call the blowfly. In his work Rangorango – Lure of the Lizards Couper explores the role of the pūrerehua to assist with spiritual undertakings. A tohunga was often required to undertake rituals that would rid an individual or community of a bad omen or kēhua (ghost or spirit). He would use the distinctive oscillations of the pūrerehua which, when played correctly, resembles the sound of a rangorango, to draw out a negative spirit, often in guise of a bright green moko (lizard). The tohunga would then capture and kill the moko, which was then eaten in order to destroy its wairua (spiritual power). The word “pure” means to remove tapu (sacredness) and can also be applied to the banishing of negative powers, while “pūrere” can mean to flee or escape.

In this work Couper has depicted the moko as a universal form. The taratara (notches) along its spine are derived from the tuatara, while the shape of the body and head are more like the gecko. The two pounamu (greenstone) moko, created by carver Lewis Gardiner, suggest the conflicted nature of this creature as a good omen, precious as a kaitiaki (guardian), and also as the harbinger of bad luck and death.

In these instances, the tohunga’s role was particularly important in ensuring the spiritual and physical well-being of his hapū (sub tribe) and iwi. When environmental conditions became difficult due to natural disasters, disease or famine, the tohunga would be called on to communicate with the atua. During these times, the pūrerehua would often be utilised in rituals such as to increase rainfall to ensure good crops. Using the instrument, the tohunga would bind together the scattered clouds and with a whakapākōkō (rattle) would make the sound of rain to get the atua’s attention. Seeds were thrown over the ritual area to indicate the fall of the rain, accompanied by karakia (prayers) and the use of an atua kiato (godstick) ( Robinson, 2005, p.153, 163 & 166). In a description by Tuta Nihoniho (Ngāti Porou), he explained how a tohunga would throw a handful of ashes to the south, which was considered the rainy quarter. He would then swing his pūrerehua and at the same time expose his buttocks in that direction while reciting an insulting karakia; angering the atua who would send the desired rainstorm in retaliation (Best, 1976, p.294).

The storm has become a recurring theme throughout this series of works. Couper describes the piece entitled Mōwai Rokiroki – Calm before the Storm as “representing all of the different facets or sides of the weather—the ferociousness and turbulence of the winds and the rain, while a contrasting calmness occurs before, in the centre and after the storm”. In creating Mōwai Rokiroki Couper has used different undercutting techniques, combined with paint effects and colours, to give the illusion of depth and to show the distinct qualities of each weather pattern. The work depicts the various layers that can occur as a storm-front approaches. As he suggests there is an apprehensive sense of calm as the sheets of drizzle, mist and fog roll across the landscape. As the wind and rain increases, they are accompanied by thunder and lightning and as the tempestuousness weather passes another period of calm descends. The word pūrerehua is also used to describe the thin and often wispy cirrus cloud that are sometimes seen during the fine weather that follows a storm.

While the previous work sought to show the visceral qualities of the weather, Huhū te Rangi – The Roaring Sky explores the intangibility of the sound and motion produced by the pūrerehua. Its distinctive low reverberation that can be heard from a considerable distance is created by its shape. Each instrument must be perfectly balanced in order to give it stability in the air and to produce the right sound. Couper was keen to explore how to visually show sound, “the work is divided into two halves – the left side represents the physical motion and the spin of the instrument, while the right half represents the vibrations and oscillations that create the instruments unusual sound.” Huhū, another name for the pūrerehua, describes the physical attributes of the sound – to buzz, swish or hum, as does the term hū, which means to resound, reverberate or boom, and is sometimes used to describe the call of the rare matuku (bittern).

Te Ahitipua a Rangi – Forces from the Heavens once again refers to the powers of the tohunga to call on the atua for assistance. Using the pūrerehua as a conduit, the tohunga would attempt to harness the raw energy of the weather, represented through the depiction of a lightning bolt, “I wanted to show how this incredible power could be utilised. I have used the spiral to show how this power was transformed by the tohunga and was sometimes channelled into assisting with growing crops or with a good fishing catch.” Employing an airbrush for the first time, Couper has tried to visually present the energy that this communion must have created.

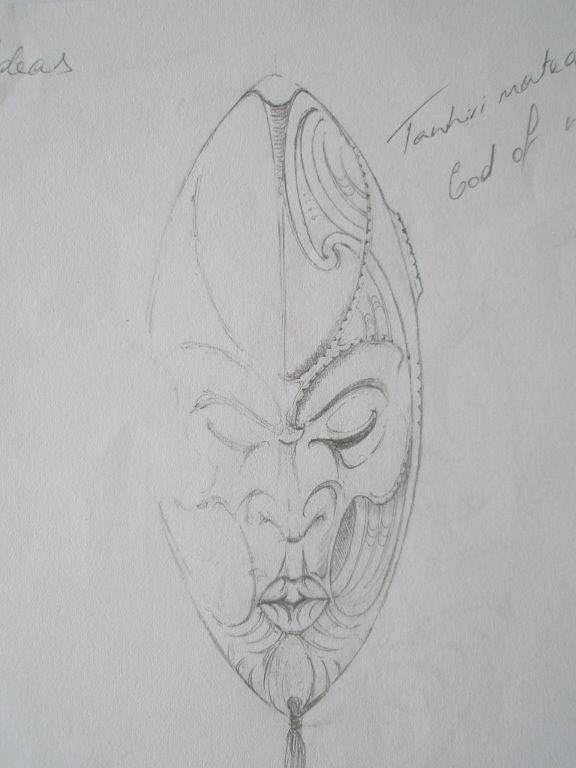

One of the gods most often called on in karakia was Tāwhirimātea, he was one the few children of Ranginui (sky father) and Papatūānuku (earth mother) to remain in the upper realms with his father and also represents a tangible link between the heavens and the earth. Māori believed strongly that there was only a thin veil that separated the realm of the gods from the physical world and that this could be bridged with the correct knowledge and tools. Some early examples of pūrerehua were heavily ornamented with carved manaia figures (bird forms). Considered a guardian and messenger, the manaia could move freely between realms. Couper’s work entitled Tāwhirimātea – Creator of Wind and Storms is the culmination of his series of new works. It is the personification of the atua and reflects many of the qualities of the pūrerehua, particularly the role of this taonga puoro in creating a connection between the physical present and the spiritual past.

The tears of Tāwhirimātea, referred to in the title of this essay, suggest a sense of sorrow and loss. However, they are not a lament, but more a celebration of the incredible potential that the future holds for those that are willing to grasp it. Using the power of the pūrerehua to guide him, Couper has used his considerable skills and knowledge, gained over many years, to explore the physical limits of this artform and to push himself to take a leap into the unknown.

References

Elsdon Best, Games and pastimes of the Māori: an account of various exercises, games and pastimes of the natives of New Zealand, as practised in former times: including some information concerning their vocal and instrumental music. Government Printer, 1976 (originally published 1925), p. 294.

Samuel Timoti Robinson, Tohunga: The revival: Ancient Knowledge for the Modern Era. Reed Publishing (NZ) Ltd, 2005.

Author

Karl Chitham (Ngāpuhi) is the Director and Curator of Tauranga Art Gallery, Toi Tauranga. He has been involved in the arts sector for over 15 years as a curator, educator, writer, selector andinstigator. Recent writing projects have included essays for Original Unknown – Suji Park and Lonnie Hutchinson: Black Bird.

Karl Chitham (Ngāpuhi) is the Director and Curator of Tauranga Art Gallery, Toi Tauranga. He has been involved in the arts sector for over 15 years as a curator, educator, writer, selector andinstigator. Recent writing projects have included essays for Original Unknown – Suji Park and Lonnie Hutchinson: Black Bird.

Comments

Good morning from ont CANADA I

So love your gallery the carving are spirtual to me thank you quick ? Are any of these pcs for sale i buy Haida products from my west coast B.C they work hard to keep their native history alive koodoos and thank you again you have touched my heart this morning with your beauty LORRAINE GARLAND