I once saw a bright garland of fresh flowers placed around the neck of a stone sculpture of Jesus in Munich in the middle of February amidst the winter snow; it remains in my mind as a very poignant image.

In European history the garland is traced back to before Roman times. In the seventeenth century, there was a revival of the garland by the Flemish artist Bruegel the Elder who collaborated with figure painters to paint devotional images of religious figures surrounded by very realistic flower garlands. The garlands were painted “from life”, and due to the accuracy of the painting, the depiction of garlands also played a part in the burgeoning empirical science movement of the time.

The lei is shared by diverse Pacific cultures and one of its forms is also made out of fresh flowers. Leis are used in greeting and saying goodbye, to honour and bestow specialness and in recognition of achievement. The giving of lei is an inclusive and connected ritual and a joyful practice; on receiving it you become acknowledged. I have spent many years teaching in Otara, South Auckland, which has a large Pacific Island community, and find graduations especially moving. They are full of emotion, with spontaneous haka, singing and lei giving. People walk onto the stage to receive their qualification and will have so many lei around their necks you can only just see their faces—drowning in lei—and then they will be taking their lei off and giving them to their teachers. it’s a shared acknowledgement of achievement, really a great ritual.

“….the typology of the lei has expanded to communicate artistic, creative and critical concerns. Practitioners from New Zealand and across the Pacific are exploring the cultural significance of the lei through their own distinctive voices.” (Simone LeAmon, Lei in contemporary Pacific cultural practice).

I continue to have a fascination with the shared landscape of who we are and where we locate ourselves and how these two things intertwine and impact on what we make. As makers navigating this space, it is important to fully acknowledge the sensitivities surrounding cultural appropriation.

“The answer is about the quality of the relationship between the person doing the borrowing and the people being borrowed from” (Lana Lopesi in The Moral Argument: A Review of ‘Jealous Saboteurs’).

Central to New Zealand identity is the immersion in a bicultural discourse. The lei, however, is very visible in the strong multicultural vibrancy of Auckland. We see it in both public and private spaces. With Auckland having such a large number of Pacific Islanders choosing to make their home here, the lei, among many other forms and rituals, has also migrated here.

Auckland, like most big cities, is a melting pot. For me, this is what makes it an exciting place to be: new immigrants and their cultures joining the indigenous. Garland forms weave through many of these cultures. Within, these forms carry not only their own histories but can also resonate with the lei form and its histories.

Alongside other works and projects, I have made ten large garland inspired pieces. Each has a long incubation period and then an intense making period. Two of them are actually called “lei”, the others are “daisy chains”, “chains”, “necklaces” and “garlands”.

I have chosen four pieces to talk about here: Urban Lei, Daisy Chains, How to make a rabbit from a sock…a necklace from a frock, and My Place.

I made my first lei in 1997. After 18 years away from New Zealand I returned to live in Auckland’s then predominantly Pacific Island community in Grey Lynn. I lived with my sister and her Malian husband’s family. The energy of the cultural mix and the feeling of being home led me to attempt a piece of hybridised jewellery; a lei of large stainless steel mesh hibiscus flowers with mascara stamens. I was thinking about different measures of beauty at the time but it became a piece for my mother.

- Fran Allison, Urban Lei, 1997, stainless steel mesh, mascara brushes, silver, stainless wire, photo: Fran Allison

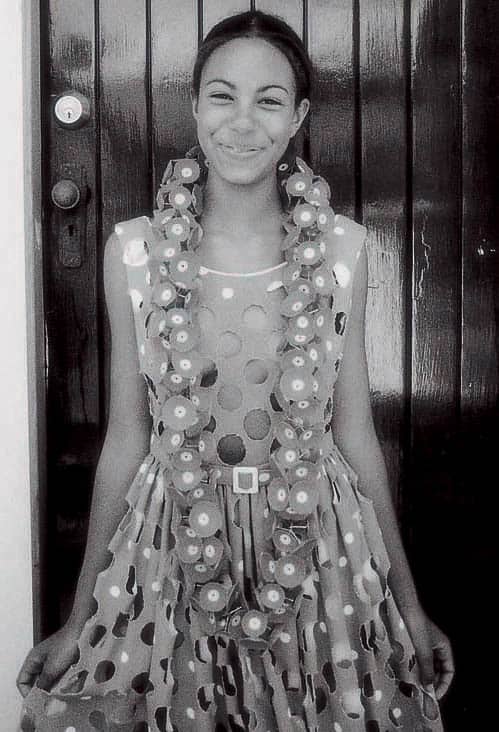

- Fran Allison, How to make a rabbit from a sock…..a necklace from a frock, 2006, 1950’s dress, lollipop sticks, silver, stainless wire, photo: Deb Smith

My practice of photographing my work on the family started with this first lei. After working all night in the shed, my mother brought me out a cup of tea at 6am just as I finished the piece. I put it on her and photographed her in the garden. This photograph has become an important link to an amazing woman and role model. I continued to photograph later works on different members of my family, my nieces and nephews, son and sisters. The inclusion of the family in the documentation has become an important part of my process.

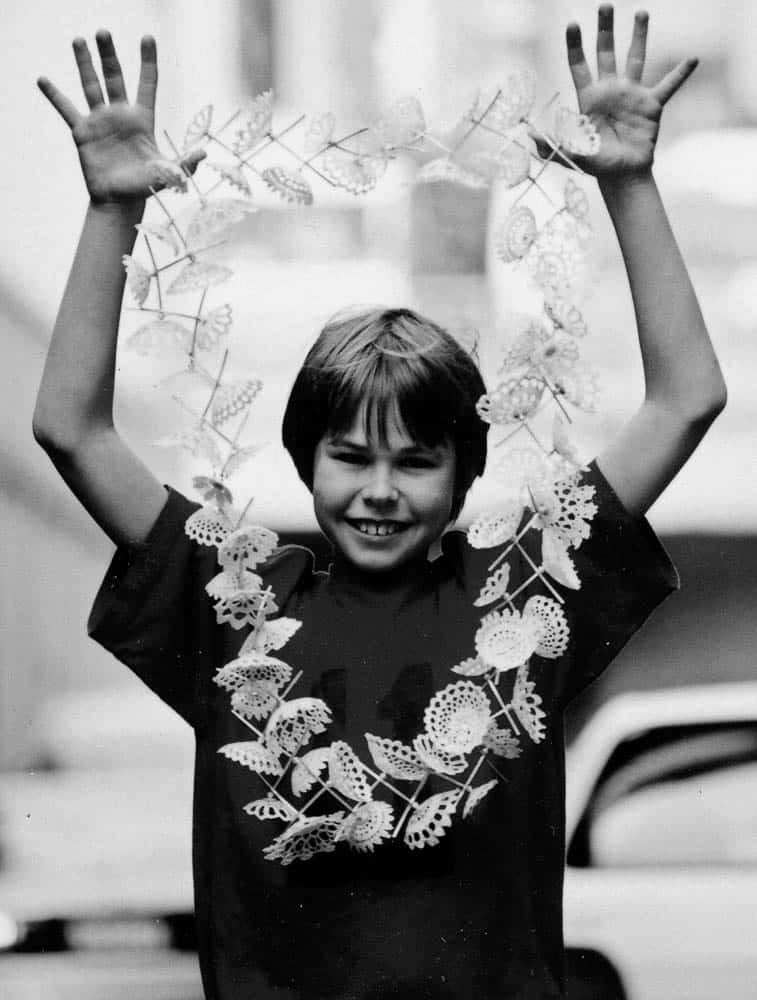

I made daisy chain works over the period of 2002 to 2010. They were made of used doilies I collected from second hand shops. They carried stains, their history of use, and allowed me to indulge in my interest in solving mechanical and technical problems with a series of ball joints and threading. They also continued an interest of mine in the role of the handmade and handicraft. They evolved out of a previous work How to make a rabbit from a sock…a necklace from a frock.

I referenced the 1950s in this particular work because that was a time of making do. I was thinking about the handcrafted hours spent making things for the home, of existing objects being transformed and altered to form new objects, and women as housekeepers. My garland was about honouring the role these women played.

The work, titled How to make a rabbit from a sock…a necklace from a frock was photographed on my niece in the garden.

Fran Allison, How to make a rabbit from a sock….a necklace from a frock – 1950’s dress, lollipop sticks, silver, stainless wire, photo: Deb Smith

Fran Allison, My Place, 6 jackets, French F2 Camo, used, 20 metre silver wire, 1 metre stainless wire, photo: Allan McDonald

In 2014 I made my second lei. My Place is one of my favourites because its subject matter is so unpleasant. The lei form is particularly important here because it is about French colonialism and its impact on the pacific.

My Place is made out of 6 French army camouflage jackets and 20 meters of silver wire. It is heavy and you become more aware of the weight the longer you wear it. It combines a semiotic reading of material and form, and the physical impact from wearing it on your body. Putting war and flowers together always creates a sense of discomfort.

Part of my artists statement includes a quote from The Epoch Times August 2012:

‘’Between 1966 and 1996 France undertook 181 nuclear weapon tests at Mururoa Atoll/Aopuni. At the time a huge toll was paid in health, lives and livelihood. Twenty-five years on, the atoll is now unstable and apparently could collapse into the sea at any time. Its collapse would release radioactivity into the surrounding area, spreading contamination across the Pacific as far as Peru and New Zealand….” The Atoll is still guarded by French forces.

I think my garlands are becoming less wearable, both physically and emotionally, as they become more political. They are physical manifestations of my mental negotiations. You locate yourself in a place, but carry with you all of your history. I am engaged in a continual unpicking, identifying my history versus my location and how and in what ratio they can mingle.

Author

Fran Allison is a contemporary jeweller living and practicing in Auckland Aotearoa New Zealand. Amongst her body of work is an ongoing engagement with the garland form which sometimes becomes a lei. The writing above came from a series of discussions between jeweller, Andrea Daly and Allison. Allison expressed her ongoing interest in how to navigate hybridised space.