Immortalised by the likes of John Milton and John Lockwood Kipling, few cities in the Subcontinent can match the glory and grandeur of Lahore.

Bearing its name from Lava or Loh, one of the twin sons of Lord Rama, the epic hero of the Ramayana, Lahore which sits on the banks of the River Ravi simply means “the Fort of Loh”. Long before it became a capital city of the Moghul Empire under the reign of the great Moghul ruler Akbar, one of the first historical references to Lahore can be found in the journals of Hiuen Tsang, a Chinese pilgrim in AD 630. The city of historical monuments and gardens is not only the cultural capital of Pakistan, but also the backdrop to the mystical Sufi saints and legendary royal romances which include Emperor Akbar’s prized mistress, the ill-fated Anarkali (meaning pomegranate blossom) and Emperor Jehangir’s beloved and brilliant queen, Empress Nur Jehan (meaning Light of the World).

Having undergone various transformations under a myriad of invaders and rulers, Lahore is a kaleidoscope of historical and cultural facets. From a fortress of security under the Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh to administrative capital under the British Raj, it was a city sought after and was branded as “the Paris of India” by the 1930s. In spite of its new residential expansion, the nucleus of Lahore remains the Walled city, a dense honeycomb of havelis (mansions), mohallas (suburbs) and bazaars enclosed within thirteen majestic darwaazay (doors or entry gates). Throbbing with a unique pulse of its own, its integrated plan of residential quarters is intricately interwoven with lively markets peddling wares like spices, vessels, cloth, footwear and local food. Enticing visitors and local residents during the day, specialised markets like Sarafa Bazaar and Rang Mahal (meaning “palace of colours”) are the domain of jewellery craftsmen practicing and selling their enviable and meticulously handcrafted ornaments, while Hira Mandi (meaning The Diamond Market) glitters at night to provide entertainment with its residential musical instrument makers and singing and dancing girls.

Lahore as a city of diversity and contrasts boasts of rapid urban expansion which has led to congestion of the many roads and alleyways that form the fabric of the city. Often vying for attention among other vehicles which includes cars, motorbikes, wagons, buses, trucks and recently the metro tram on the chaotic roads, the rickshaws are perhaps the strongest evidence of the frantic rural-urban migration which has been steadily increasing every year. This humble machine proves to be the ideal mode of transport in terms of being suitably cheap, easily accessible and effortlessly manoeuvrable as it teeters through the twisting and turning narrow gallis (laneways) of Anarkali Bazaar, Shahi Mohalla and the Walled City. Its eccentric existence not only reflects the varied socio-economic landscape of the city but its quirky form and surface decoration is symbolic of the cultural and aesthetic values of the region.

- Rangeela Rickshaw in Walled City

- Ornamented Rickshaw back

- Embossed and perforated tin sheet decorated accessories

The traditional art of vehicle decoration is a well-known phenomenon and an integral part of the visual culture of Pakistan. Heavily ornamented trucks are an iconic representation of this vernacular form of art which stems from the cultural practice of decorating even the simplest of everyday domestic objects and spaces and can be traced back to the ancient societies of Mohenjodaro and Harrapa from the Indus Valley civilization. This particular style of expression known more popularly as “Truck Art” has manifested itself onto various modes of rural and urban transport, irrespective of scale and form, like Tongas (horse-drawn carriages), buses, wagons and rickshaws. It has made international appearances on the buses of London and the trams of Melbourne to cultivate cultural connectedness.

The conceptual underpinnings of this art form lie in the overlapping and multi-layered beliefs and customs of the land, where the vehicle is not just a form of transport but a source of livelihood and thus an object of pride for the owner. Ornamenting it is an act of invoking the blessings of God, the provider of that livelihood and thus ensuring the safety and protection of the driver from both the “seen” and the “unseen” dangers of the journey ahead. The exterior and the interior of the vehicle is a canvas for provocative imagery coupled with religious verses, Sufic stanzas and idiomatic sayings like Maa ki dua, Jannat ki hawwa (A mother’s prayer is like the gentle breeze of Paradise) to bestow good fortune on the owner of this coveted vehicle as he sets out to face the perilous voyage across towns and cities to wherever his destiny leads him.

The Rickshaw is believed to be borne in 1867 from the imagination of a Japanese trio in a bid to upgrade the horse-drawn carriage and its name originates from the word Jin riki shaw which means “man-powered car” Within a decade, Japanese streets were host to around 200,000 rickshaws, and although this invasion did not take over the streets in Japan, this humble form of transport spread to many Asian cities in the neighbourhood, each region customizing this rickety machine with intricate adornment and accessories thus giving it a distinct personality of its own. Its transition to the auto-rickshaw came when Bajaj Automobiles India was given the manufacturing license by Piaggio in Italy, whose designed utility vehicle the “Ape” was the precursor to the form we see today.

The three-wheeler with its curved bee-like body is fashioned out of a lightweight frame of metal sheet and a canvas roof, roll-up windows and doors and incorporates a handlebar steering and a two-stroke engine. With a weight of less than 300 kilograms and a driving speed of 30km per hour, it was designed as a public transport vehicle optimised for agility and efficiency and offers a “luxury” door-to-door service due to its compact form which allows it the freedom to weave through small narrow spaces to pick up and drop off passengers at random spots. The rickshaw has transformed rapidly into the preferred mode of transport in urban Pakistani cities much like its distant and not-so-distant cousins: the Tukxi in Italy, the Bajaji in Madagascar, the Tuk-tuk in Thailand, Jeepneys in the Philippines and the Auto in India.

The rickshaw owner is the patron of this creative contraption, but it is the artist who ultimately interprets its owner’s narrative of whims and desires and portrays it onto the vehicle with an unchallenged creative licence. The intricate ornamentation of the rickshaw starts at the assembly workshop and includes several mediums and techniques like oil paint, applique, tassel making, tin sheet perforation, sewing and stencilling and involves the skill and patience of the ustad or master craftsman, the mistris or apprentices and the body maker workmen. Depending on the place of origin and the budget, the decorations may include LED lights and designs painstakingly cut in chamak patti or reflective tape.

A smorgasbord of images tickles the palate of imagination inspired by virile film heroes and voluptuous damsels in distress from local cinema billboards to idyllic panoramic views with exotic Peacocks and Birds of Paradise. With the influence of the media, these neo-romantic themes are often interrupted with political imagery or display a collective socio-cultural expression. Glorifying the latest missile developed by the armed forces or the presence of a large stylized F-16 fighter jet are blatant interpretations that superimpose on the tranquil, panoramic views of northern Pakistan. More recently, bold portraits of school girls adorn the vehicle to promote rights to education for women, a much-welcomed relief from the rhetoric of war. The chand (crescent moon) and sitara (five-pointed star), elements from the national flag, further reinforce the notion of solidarity of the country.

Textual elements in the form of popular idiomatic phrases, poetic verses and advertising slogans jostle for space with each other. Portraits of doe-eyed females, a visual metaphor of the unattainable, compete against fervent proclamations of miracle treatments for infertility or inciting taunts at the “unbelievers”, coaxing them to mend their ways by attending an upcoming religious convention. Objects like a child’s flip-flop sandal or a miniature embroidered khussa (ornamental leather shoe) and a black scarf hang precariously from the lower end at the back of the rickshaw, a good luck charm believed to protect the driver from the “evil eye” and superstitious forces. For the vehicle following the sputtering rickshaw in the frenzied bumper to bumper traffic, it is a menacing distraction, swaying hypnotically to the deafening chorus of honking and tooting cars and the drone of motorbikes whizzing and scraping past like angry hornets.

One remarkable feature of this art form is the command over geometrical symmetry. Whether in the form of mirror images or a careful balancing act of integrating abstracted and stylized elements to reflect symmetrical unity, the aesthetic skill on the part of the rickshaw artist can be called none other than impeccable. Two gaudy peacocks flank a hybrid lotus flower which forms the central focal point. In some instances, overlooking these creatures of Paradise are two mischievous Mian Mithu parrots, their brilliant green plumage and gleaming red beaks outshining an innocent pair of plump pigeons in a heart-shaped embrace. A timid brown Quail huddles on the edge, content in its solitude and safely shielded from the cacophony of its housemates. Its peaceful sanctuary is sometimes intruded upon by the sharp, menacing outline of a magnificent eagle, soaring high above the icy peaks of the Himalayas.

This joyous carnival of colour is often graced by the royal presence of two elaborately rendered figures, a bejewelled Mughal raja (king) with his beloved rani (queen) enjoying a blissful moment under the glimmering starry skies. Cascading waterfalls, delicate friezes of flowering vines, fish and butterflies along with eye-catching patterns of contrasting lines and geometric shapes frame this opulent world. Rich in symbolism, it is an allegorical journey into the dizzy pursuits of mortal beings in their quest to shun worldly luxuries to focus on their ultimate goal to ascend to the eternal garden of heavenly delights – a promise which is too tempting to ignore for the majority of the population stuck in the tireless grind of everyday life.

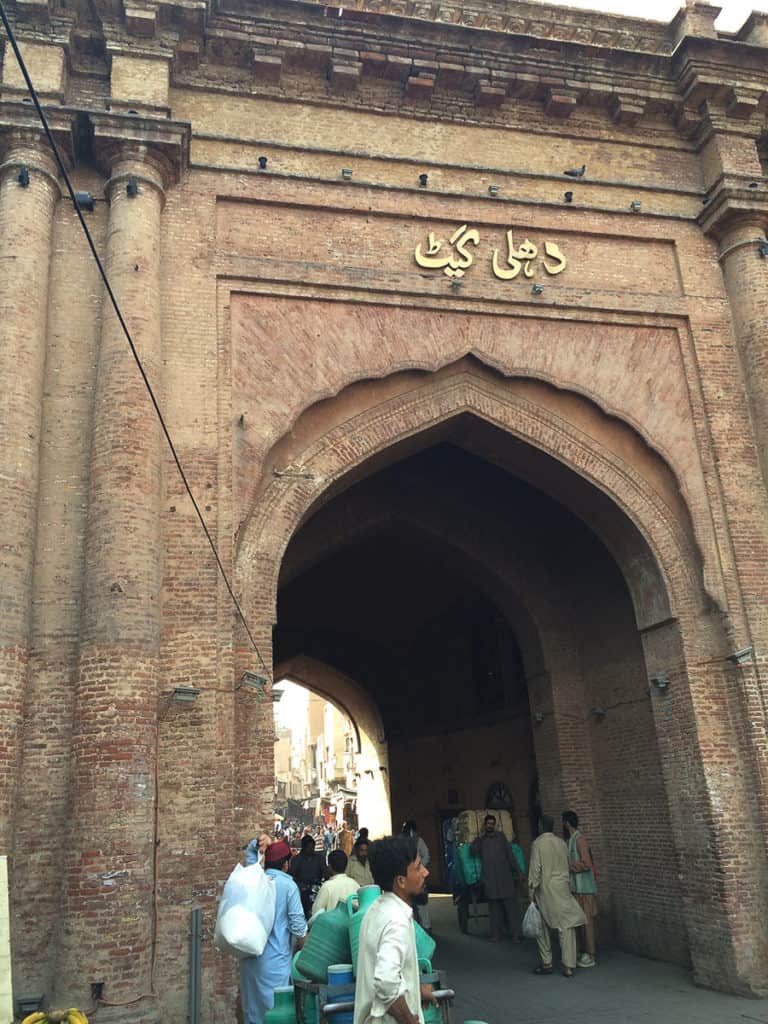

- Delhi gate entry into Walled City

- Narrow alleyways in the Walled City

- Frescoes, Kashi Kari tile work and Jharoka on the Wazir Khan Mosque

- Brass wares with repoussage

- Antique jewellery seller in Walled City

The Rangeela Rickshaw ride, an initiative of the Walled City of Lahore Authority, is a peep into this imaginary world. Inspired by and decorated in the “Truck Art” style, the rickshaw gives locals and visitors to the city a chance to experience the visual culture of Lahore. Designed as a craft tour, it aims to encompass an authentic understanding of the life and culture of the Walled City and offers a roller coaster ride of visual and sensory treats. Starting at the Delhi Gate, one of the arching entryway gates into the Walled city, it is “the best route to adopt in order to see the most picturesque portions” as Kipling & Thornton advise in the 1860 travelogue Lahore as it was. A fleet of richly ornamented rickshaws greets visitors with the promise of a ride of a lifetime. Indeed, for those unfamiliar with life in the old city, it is an eye-opener of sorts. Starting from the rickshaw itself, embellished like a bride on her wedding day, the bold display of painted illustrations and carefully crafted trimmings coming to life with blinking LED lights are just a glimpse of what is to follow. Jiggling to the blaring tunes of Punjabi-Bollywood jhankars (remixed songs and/or music), these vibrating vehicles unabashedly steal the show before the ride of fantasy even begins!

Like gaudy showgirls strutting their stuff to a delighted audience, the queue of Rangeela Rickshaws invite stares of pride, glee and excitement as they pass through the crowded lanes along a predetermined route, often braking to an abrupt halt amid the throbbing mob of traders, customers, hawkers, swindlers, beggars, unassuming pedestrians and domestic animals. As the ride winds and wobbles through the surreal and the sublime, stopping at spots like the Shahi Hammam (The Royal Bathhouse), Wazir Khan Mosque and Pani Wala Talaab before its last stop at the Food Street behind the Lahore Fort, the passengers experience a whirlwind of sights, sounds and smells unlike any they have encountered before. The jewel-like ceilings of the Shahi Hamaam, the delicate botanical wall frescos and Kashi-Kari (glazed tile work)on the Wazir Khan Mosque and the balconies and jharokas (a style of overhanging enclosed balconies in Indo-Islamic architecture) of the Haveli Baij Nath mesmerize the mind and evoke the senses as we ride along the Shahi Guzargah, the royal trail used by the processions of the Mughal emperors travelling from Delhi to the Lahore Fort.

Greeted by the pungent whiff of spices as we approach Akbari Mandi and passing through the noisy din of Kasera bazaar with its gleaming metal vessels and ornamental repoussage wares, we stop for a local snack of Dahi Bhalay (lentil dumplings in a sweet spicy yogurt mix) at the foot of a long chalky stairway leading to the tomb of Pir Bhalki. Overwhelmed by the fragrance of rose petals and incense, our journey continues past the three gilded domes of the Sonehri Masjid or Golden Mosque through to Baoli Bagh, the garden of the multi-levelled stepped wells, once a magnificent oasis but now barren and neglected. As we approach Langa Mandi, the melancholic lament of the harmonium accompanied by the deep booming beat of the tabla (drums) echoes the frantic rhythm of everyday life in this city. The tour officially ends at Food Street, lined with a lively array of local food shops and restaurants offering gastronomic delights that make you feel like a king as you are served one elaborate meal after another while taking in the breathtaking view of the Lahore Fort and the Badshahi Mosque.

The humble rickshaw may be the only vehicle of choice for many of the residents of the Walled city as they go about their daily lives, but the ride is akin to flying on Aladdin’s magic carpet. Seamlessly weaving our way through the grand historical sites, mystical mosques and the karkhanas (workshops) of cobblers, pipe-makers, black smiths, jewellers, bangle makers, twine weavers and carpet weavers, the multilayered facets of a microcosmic world is revealed. Home to generations of skilled artisans, once patronised by the mighty emperors, the Walled city still remains the hub of the traditional craft industry where caste nor creed matters.

Occupying a revered social position historically across many cultures, the knowledge and skills of craftspeople were associated with unique sacred or ritual qualities. The truck and rickshaw artist’s craft is a reflection of the social and cultural realm through its distinct depictions of historical, political and neo-romantic themes. Creating a narrative rich in metaphorical and lyrical expression, the images, objects, forms and abstracted elements adorning trucks and rickshaws are a distinct blend of folk, quasi-religious, rural, urban and Pop art—an ode to the poetic imagination of the contemporary artist. As “social actors”, these artists and artisans manifest the socio-cultural dimensions of craft where craft production itself is a social act and the craft producers are shapers of the system and the products they create.

Moreover, this vernacular art form challenges the formal institutions of art whose privileged positions of self-created hierarchy dominate the value chain of aesthetics. Aptly stated by Lahiri-Dutt and Williams in the publication Moving pictures: Rickshaw art from Bangladesh, the rickshaw intrudes this carefully guarded realm “by going into the most public of public spaces, the streets, (where) it resists the custodianship of the galleries and the intellectual assessment of the art critics. Consequently, rickshaw art remains fluid in meaning and resists appropriation by cultural gatekeepers who also attach values to the places where ‘proper’ art can exist. In its use of the public space, crucial in understanding its spatial and cultural politics and in locating it in places other than where art ‘belongs’, rickshaw art redefines art and the legitimization of it.”

The tinkle of the courtesan’s ghungroo (metal bells) and the wailing tunes of the snake charmers may have become a faint memory but an empire of artistic triumph continues to pulsate in the narrow alleys and dimly lit streets making Lahore live up to its reputation as the “gem” in the crown. Indeed, its glorious existence is celebrated in the popular Punjabi expression: Jine Lahore nahin vekhya au jamia ee nahin.

One who hasn’t experienced Lahore has yet to be born

Author

Sahr Bashir is an art educator and a visual artist living and working between Pakistan and Australia. Through her teaching and art practice, Sahr seeks to explore the symbiotic relationship between the maker, wearer and the viewer in our everyday engagement with jewellery and objects. Her role as an Art Jewelry Forum Ambassador involves encouraging conversation on a global forum through training workshops, writing and collaboration. Her website is www.sahrbashir.com.

Sahr Bashir is an art educator and a visual artist living and working between Pakistan and Australia. Through her teaching and art practice, Sahr seeks to explore the symbiotic relationship between the maker, wearer and the viewer in our everyday engagement with jewellery and objects. Her role as an Art Jewelry Forum Ambassador involves encouraging conversation on a global forum through training workshops, writing and collaboration. Her website is www.sahrbashir.com.