Aarti Kalwa introduces the lecture by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay which advocates for the idea of world craft.

For Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya (1903-1988) and other Indian nationalists, crafts revival and independence from British rule were interlinked agendas. In her view, cultural self-determination was as much the need of the hour as political independence, to stall the economic, and cultural retardation experienced by continents like Asia and Africa under colonisation. Speaking on the role of crafts in the preservation of cultural values at the First World Congress of Craftsmen held in New York in 1964, Kamaladevi drew attention to the contemporary significance of crafts: “Craftsmanship need not, however, be bound up wholly with tradition. While it continues to draw strength from the past, it has also to be tuned to the present, evolve a new relationship with the current flow of life .…” For her, crafts were not only a way of recognising the significance of one’s own culture but also, of developing a sense of appreciation of other world cultures as well.

Like other craft advocates of her time, Kamaladevi’s aestheticization of artisanal labour over that of the factory worker was a matter of good taste but also a political choice and a cultural ethic. She believed that no mechanised operation could replace the intimate kinship between a handmade object which was created to be in perfect harmony with the user who in turn gets “as much satisfaction from the right kind of spoon as from the food to be eaten.”

Aarti Kawlra is Academic Director, Humanities across Borders, International Institute for Asian Studies, Leiden The Netherlands

✿

Mme. Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Chairman All India Handicrafts Board, New Delhi, India: “Preservation of the Cultural Values of a Society Through Craftsmanship”, The First World Congress of Craftsmen, New York, 1964

There is a growing anxiety about traditional cultures that are dying or have already disappeared, and a question whether their decay should be arrested. This anxiety (which at times turns almost to bewilderment) is all the keener in older countries such as some in Asia and Africa, where certain aspects of cultures that once made powerful impressions are disintegrating under new impacts. The main characteristic of such cultures was their hereditary nature. The major developments occurred within families, or kindred communities, and were handed down from generation to generation through practice and tradition. The younger generations grew into established patterns of faith, social living, and economic vocation. This ensured easy cultivation and avoided waste of time and effort. The valuable experiences of generations gone by, the epics, tales, parables, proverbs, and songs that their lively imaginations gave birth to, served to enrich the growing minds.

Plato identified culture with discrimination between good and bad workmanship. In India, it presupposes the qualities of memory and detachment, a capacity for stillness of mind and body (restlessness is regarded as uncultured), all of which aids in developing the power to penetrate the mere externals in men, races, and matter. In ancient Vedic times, the Hindu mind regarded culture as a view of life where true and false values are not confused. It saw reality as the embodiment and source of the three ultimate values: truth, goodness, and beauty. Man’s mission came to be seen as a search for the source of all that is good, and therefore all that is beautiful. This source is called God. Thus, “God, may we attain all things that are beautiful,” is one of the earliest Vedic invocations. The poetic mind of the early Indo-Aryan was attracted towards beauty as an attribute of the eternal order that had been wrought from the anarchy of matter. But the order is not just mechanical. It goes into a realm of beauty which lifts man above the perception of mere physical structure to a keener perception and experience of a loveliness that is believed to be the reflection of the beauty, the primordial source, from which it originated.

And so if we can accept culture as the cultivation of this kind of sensitivity, its relationship to crafts becomes obvious. In the early Hindu society, beautifying became a duty, then a ritual. Painting on walls, drawing designs in front of houses and on doorsteps, ornamenting the place where one sat down to eat was creation with a purpose. No aspect of life was too humble for it, no article of use. Where beauty became equated with truth and with God, a woman had to have certain embellishments, ornaments, beauty marks on face, hands and feet; these came to acquire sanctity, as signs of good omen, and even as a requisite minimum of decoration in the house. The use of special articles for special occasions in the way of clothes, jewels, vessels, etcetera (all of which had to have quality, even in daily life) meant for the owner a continuous outflow of creativeness, a sustained spirit of freshness, that dispelled monotony.

Craftsmanship everywhere serves to create an instinctive appreciation of beauty rather than a self-conscious striving after it with a superficial veneer of sophistication. It calls for a subtle understanding of composition even as in any work of art, to use the combinations of form and curves to advantage, avoid odd or awkward empty spaces by filling them up appropriately to form a contrast with the more ornamental parts, and making the lesser parts stand out more clearly, and also blending and highlighting the luster and mellowness of light and shade.

Craftsmanship is the indigenous creation of the ordinary people. It is a part of the common life, not cut off from the main stream. Originally craftsmanship grew up in the countryside where a community evolved a culture of its own out of the steady flow of its own life and of the nature around it. It was the product of an unhurried rhythm and the spell of serenity, as contrasted with the bustle of the present day. The products had a vitality of their own, as they were the direct expression of the craftsman and his emphasis on the functional beauty of the article. At the same time, a very significant factor was the anonymity of the product, which is in striking contrast to the present age of signatures and publicity. Beauty was an end in itself, and service to the community a source of complete satisfaction. The name of the maker added no more to the quality or value of the article. What is of great significance is the status assigned to, and the security provided for the craftsmen from the gnawings and paralyses of anxiety. A craft-oriented society was based on personal relationships, not contract and competition.

In India, the craftsmen owed allegiance to Viswakarma, the god of the crafts (one community of craftsmen even claimed direct descent from Viswakarma himself). They enjoyed high social status and were entitled to special privileges. On occasion they even acted as spiritual guides and priests. There is a week dedicated annually to Viswakarma, when the craftsmen set up his image, along with the craft tools and implements, and worship with gay celebrations. Thus craftsmanship has been imbued with idealism not normally associated with an industrial pursuit. It was not just the plying of a trade, but a social act. It was not conceived of as an accumulation of skill over the ages, but as ability continuously received from Viswakarma. Our ancient books say that when the hands of a craftsman are engaged in his craft, it is always a ceremonial. Beauty expressed in form and rhythm was regarded as an abiding entity, which enjoyed an absolute existence on an elevated plane, where all who sought could find it. Thus the craftsman was encouraged to rely more on his inward inspiration than on external force. “The craftsman must be a good man,” enjoin our ancient books. “He must be devout, charitable, free from avarice.”

Against this rich background, the ideal of the aesthetic began to take shape very early. Sensibility was called for as the basic requisite for aesthetic experience. The man of taste was rated as gifted in sensibility as the man who created. So appreciation was, in a sense, on par with creation, because a man of sensibility participates with almost the same excitement and exhilaration when he appreciates as when he creates. This concept is an important and integral part of Indian faith and thought. Insistence on good taste created a high standard for arts and crafts. Even the common terracotta showed both a vigor of muscle and a flow of line, to prove, as it were, that the earth is not a static but a dynamic rhythm, realized in flux through a continuous process. Craftsmanship involved the cultivation of an intimacy with human life, of sympathy for all living things, and a realization of the unity in diversity.

Tools were regarded as the extension of the hand to reach beyond the range of human limitations. The craftsman thus combined the functions of conceiver and executor. He symbolized for his society the outer manifestation of the creative purpose. He was the unbroken link in a tradition that embraced both producer and consumer within a social and religious fabric, so unified that anyone impairing the efficiency of a craftsman was put to death.

Craft and aesthetics were deeply rooted in function. Ornamentation and decoration were not divorced from utility. And though design was based on tradition, the productive act was freed from imitation through its source in the stream of life, which made it a dynamic manifestation of man’s endeavour to express universal emotions and interests.

In the economic sphere, village craftsman traded by an exchange with one of an equal i occupational standing. Moreover, the craftsman was considered an important entity n society, who, by performing valid functions for the community, became entitled to a certain status and freedom from care in old age and sickness. In urban areas, they had guilds to tend to their interests, since they did not live in such well-knit communities. These guilds took great pride in giving their services to build temples and monuments, decorating and sometimes even maintaining them.

In India, from very early times down to the Moghul period, the highest in the land — that is the king and the royalty — worked in crafts. There is a story about a craftsman who refused his daughter to a sultan unless he learned to practice a craft other than statecraft. A king of Ceylon, in days gone by, used to teach crafts himself to his talented subjects.

Even though craftsmanship was hereditary and was passed from generation to generation, inheritance of skill, as such, was not assumed. The emphasis was on proper education and right environment for the growing youth. Hereditary craftsmanship meant that the young craftsman was brought up and educated in the family workshop as the disciple of his father, uncle, elder brother, or whoever happened to be the head of the family. In these workshops, techniques were taught in direct relation to basic production and problems, primarily through practice. Moreover, the pupil also learned metp.physics and the true value of things — in short, culture. There was no isolation from larger life, as the aim of education was understood to be the unfolding of the personality. The quality of inspiration which transmutes skills and competence can hardly be taught. It has to be cultivated by training and experience, and this made for a very special relationship between the teacher and the pupil. The latter looked up to the former as the source from which knowledge came, great truths were learned and interpreted. The teacher educated the pupil as much by his personal conduct as through studies.

The teacher in a craft society was also a social leader, and not a servant of an institution or on the payroll of an individual. He owed allegiance only to learning, to which he dedicated himself. Moreover, teaching was enjoined upon all men of learning as a duty to society. The teacher kept no trade secrets from the pupil. He spurred the pupil to surpass himself and took genuine pride in conceding superiority to his student.

A society dominated by mechanical industrialization exalts efficiency over creative gifts, but it has to be remembered that overemphasis on techniques, as divorced from imagination, can result in lack of the exaltation which stimulates the capacity for creative action.

Also, making what are called “facts” pivotal in education can drain away all inspiration and leave life too flat to awaken any sense of wonder in the young. This obsession with facts can be as hard to shake off as the superstitions of fancy.

More and more use of automatic machines now curtail the demands on man. Less and less of him is called into action. Geared to automation, human beings increasingly conform to machines and individual opportunities for choice and decision narrow. One is gradually becoming aware of a lowering of standards in the current age, as compared with the olden days of the craft age. Taste is determined more by fashion than by the intrinsic value or merit of a product.

It is significant that the regeneration of crafts was made part of the national freedom movement by Mahatma Gandhi. According to him, freedom was not to be defined in political and military terms only, but also in the social patterns that would lead to building inner personality, the spiritual content of the nation. As a subject people, we had so long been under external pressures and compulsions that even our imagination had become captive, prone to imitate and depend on alien cultural expressions that often vulgarized our sensitivity by superimposition.

The national regeneration of the people, as Gandhi visualized it, was to come through the recreation of ideals, aspirations and dreams shaped partly through objects of craftsmanship with which they lived. For, in craftsmanship, the creative impulse that comes from the people is infused back into their undertakings. A very special word at the time was Swadeshi — “of the land.” Although normally it means “products of the land,” in Gandhi’s connotation it meant much more. It was a way of life, conforming to and upholding enduring values that enjoined gracious living and rejected unlovely utilities.

In upholding craftsmanship one does not by implication reject machines or make an impassioned plea for a return to hand production. There is, in fact, a basic relationship between small tools and large machines. Where we take the wrong turn is in failing to make the proper appraisal of the role of each in its own sphere. Tradition respects the natural limits of craf tsmanship and the harmony that is established between the craftsman, the materials he uses and his tools. The pride he derives from his creation and the delight in the perfection of his finished product sustain him. The machine, on the other hand, makes physical existence easier and more comfortable, although it tends to make a man feel rather small and ineffective, one who does not have the satisfaction of being supreme in his own sphere.

As is said, eating calls for as much satisfaction from the right kind of spoon as from the food to be eaten.

The very fact that even in our fast growing forest of machinery, far from getting smothered, crafts are once more coming into world focus, emphasizes that within us pulsates an innate yearning to use our hands and to feel the surface of handmade things. Craftsmanship embodies a depth of experience very different from studio work. The problem posed is not man versus machine but rather a harmony and cohesion between the two, a regulating of each in its own appropriate field. In large-scale industrialization, the machines carry out the mechanical processes that do not call for creative skill and can save the talented craftsman from routine drudgery. On the other hand, craftsmanship still forms part of the daily environment and fills it with rhythm and stability. The need for saving and developing craftsmanship is felt as vital even by those caught up in other pursuits, for it enables us to maintain contact with those aspects of our culture characterized by craftsmanship and to absorb some of its elegance and grace. Particularly with young people, craftsmanship is enormously important because of the personal qualities which it helps to develop. Craftsmanship has a special vitality as a direct human answer to a direct human need. As is said, eating calls for as much satisfaction from the right kind of spoon as from the food to be eaten. Craftsmanship is, therefore, an intimate kinship with, and understanding of, the human needs the products serve, that induces an intuitive sense of going with, rather than against, the grain of life. On an assembly line, it is rather man adjusting himself to the machine. Craftsmanship helps to harmonize life with nature, and there is greater freshness and spontaneity in it than in the monotony of the machine operation.

Craftsmanship need not, however, be bound up wholly with tradition. While it continues to draw strength from the past, it has also to be tuned to the present, evolve a new relationship with the current flow of life and thus create a new tradition. But there are certain values indispensable to mankind which craftsmanship reserves, and those craftsmen and craft lovers who draw on the perennial spring of inspiration as of old, can still realize and experience that same sense of fulfillment.

The long centuries of political and economic rule of some regions by others are giving way, and now, as the less industrially developed areas emerge from the old suppressions, they come to a proper perspective, with a growing realization of the significance of their own cultures and their contribution to a world culture. The people of the former ruling countries, too, are waking up to a greater discernment and appreciation of the gifts and qualities that the newly freed have to offer. Today, much of the old obtuseness and casualness on the part of the ruling peoples towards the less industrialized nations is giving place to a more intelligent and sensitive understanding of the old cultures, traditional values, and the need for mutual understanding, appreciation and exchange. There is also a realization that an older way of life is not to be swept away like so many cobwebs, that it reveals untold charms and subtle and restrained overtones that have abiding values and a living vibrant message. Anand Kurnaraswamy, the great interpreter of oriental arts and crafts to the world, says, “Years ago, under pre-industrial conditions, the public had perforce to accept good art, good design, good coloring, because nothing worse was available.”

Now mass production places the ignorant, aesthetically untutored at the mercy of those who seek larger and larger profits. The time for choice has come. Good taste and good opportunity to live in intimacy with beauty should not be the privilege of the few, but the common inheritance of all. This is what craftsmanship has to teach and offer us.

While we strive to cherish and develop each our own regional and national crafts, we are also becoming responsive to unfamiliar shapes and forms of other countries. While we do not desire to be steam-rollered into one common expression, we could gradually grow to the happy realization of a common and universal heritage. One is enriched by the contrasts and exhilarated by the ever new contacts and responses. The frontiers of our sympathy are extended and our human affections deepened by sharing craft creations.

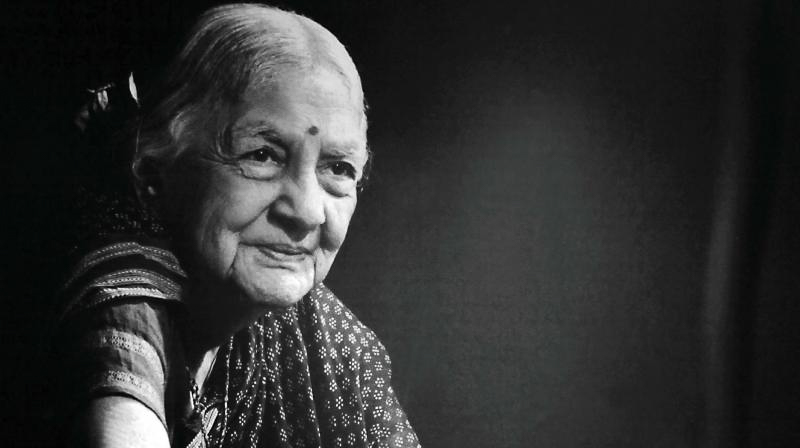

About Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (3 April 1903 – 29 October 1988) was an Indian social reformer and freedom activist. She was most remembered for her contribution to the Indian independence movement; for being the driving force behind the renaissance of Indian handicrafts, handlooms, and theatre in independent India; and for upliftment of the socio-economic standard of Indian women by pioneering the co-operation. Several cultural institutions in India today exist because of her vision, including the National School of Drama, Sangeet Natak Akademi, Central Cottage Industries Emporium, and the Crafts Council of India. In 1974, she was awarded the Sangeet Natak Academy Fellowship, the highest honour conferred by the Sangeet Natak Academy, India’s National Academy of Music, Dance & Drama. She was conferred with Padma Bhushan and Padma Vibhushan by Government of India in 1955 and 1987 respectively. She is known as Hatkargha Maa for her works in handloom sector.

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (3 April 1903 – 29 October 1988) was an Indian social reformer and freedom activist. She was most remembered for her contribution to the Indian independence movement; for being the driving force behind the renaissance of Indian handicrafts, handlooms, and theatre in independent India; and for upliftment of the socio-economic standard of Indian women by pioneering the co-operation. Several cultural institutions in India today exist because of her vision, including the National School of Drama, Sangeet Natak Akademi, Central Cottage Industries Emporium, and the Crafts Council of India. In 1974, she was awarded the Sangeet Natak Academy Fellowship, the highest honour conferred by the Sangeet Natak Academy, India’s National Academy of Music, Dance & Drama. She was conferred with Padma Bhushan and Padma Vibhushan by Government of India in 1955 and 1987 respectively. She is known as Hatkargha Maa for her works in handloom sector.

Further reading