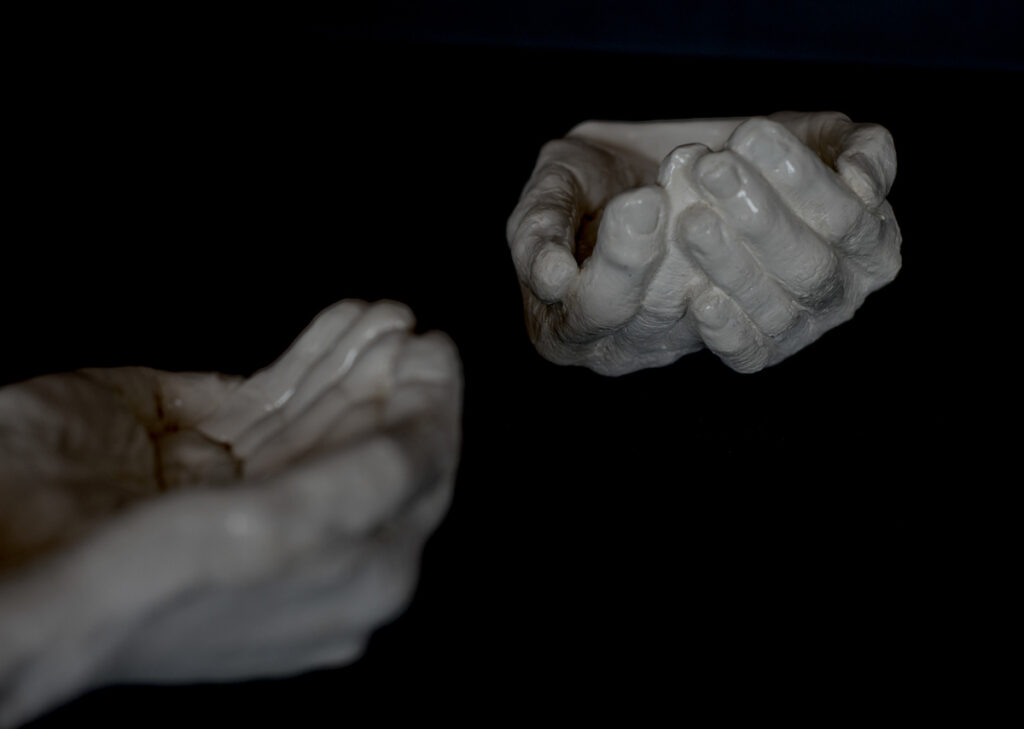

Alma & Brett Studholme, 2019, video with sound, duration 15.32 minutes, still, daughter (left) and mother (right)

Alma Studholme admires an exhibition by Jayanto Tan and reflects on her own work that bridges migration with the warmth of a teacup.

I recently encountered work by a Sumatran-Chinese Australian artist Jayanto Tan at Parallel Wanderings group exhibition in the Art Space on The Concourse in Sydney, Australia. It made me revisit my long-lasting fascination with simple, yet universal and timeless everyday ritual of sharing a cup of tea.

The exhibition is part of the 2022 Lunar Year of the Tiger Festival in Chatswood, held from 27 January to 20 February. It features Tan’s work composed of three natural-looking, bark-like “sheets.” Suspended from the gallery ceiling, they are cascading down to the gallery floor. At the same time earthy and evocative of a waterfall, they form a single installation. I was immediately drawn to this work by its elegance and its simple beauty.

Its poetic title, Sacred Gathering in the Moon Garden, further enticed my curiosity. However, finding out it was created from used teabags, as well as learning about Tan’s immigrant story, led to a deep enchantment, recognition and connection with his thoughtful and touching art offering.

- Jayanto Tan, Sacret Gathering in the Moon Garden, 2022, used tea bags, photo Brett Studholme

- Jayanto Tan, Sacret Gathering in the Moon Garden, 2022, used tea bags, detail, photo Brett Studholme

To give a background for this personal encounter, I should mention that Buddhist contemplative practices, such as Japanese Zen Buddhist channoyu or tea ritual, are a frequent subject of both my academic and my art practice. I sensed something of a shared sensibility in Jayanto Tan’s work regarding these types of meditative practices.

As an academic researcher, I am often drawn to observe them in the context of cognitive sciences. This helps deepen my understanding of the embodied mind’s inner workings in the performed contemplative rituals.

At the same time, my own art practice relies on experiences of the very processes I study. When working with clay, or engaging in a performance, I regularly feel my thoughts retreating to the pre-reflective background. My body takes the lead in the search for a complete immersion in the play that shares much of the meditative, ritualistic and repetitive features with its contemplative religious counterparts.

Whilst I would say that both Jayanto Tan’s installation and my own work emerge from similar concerns with “ritual, meditation, healing and time,” I also recognise their germination within personal liminal spaces we each inhabit in our own unique ways. Tan’s story is that of a North Sumatran immigrant to Australia, and mine of a Croatian migrant relocating with her Australian partner to his country.

Both Tan and I seem to inhabit a place-in-between two worlds: our homeland, where our birth-families remain, and our newly found homes in Australia, from which each of us dreams of and longs for the warmth of a physical connection with the loved ones far away.

We also seem to dwell inside the creative spaces inherent to art practices where imagination forges creative healing rituals. These “art rituals” become embodied attempts at re-establishing, deepening or attempting to deepen our awareness of the spiritual connection with the family across the vast “water and land divide.”

Jayanto Tan’s installation shown at Parallel Wanderings involved collecting and drying used teabags as a psychological ritual providing healing for the felt loss of his homeland and his family. Remembering plays a crucial role in this process and Tan mentions (with noticeable reverence) “memories of his beautiful mother” in the same breath as “his own healing by collecting used teabags from many cups of tea, in order to explore cross-cultural aspects between East and West.”

- Alma & Brett Studholme, 2019, video with sound, duration 15.32 minutes, still, daughter (left) and mother (right)

- Alma Studholme, Daughter’s Hands Tea Cup (bottom left) and Mother’s Hands Tea Cup (top right), 2019, ceramics, photo Alma Studholme

- Alma & Brett Studholme, 2019, video with sound, duration 15.32 minutes, still, daughter (left) and mother (right)

This very dynamic between the physical presence and absence, between deep spiritual connection and longing for its physical aspects, is also present in my own body of work which started to form soon after arriving in Australia. My own project finally came to its realisation two years ago, when my partner and I last visited family in Croatia.

In a short film Three Waters: Tears, Tea, Sea created in collaboration with Brett Studholme, my mother and I perform a deeply personal tea ceremony. The split-screen of the video shows a mother and daughter separated by the sea, yet joined by a performance of the single tea ritual. Filmed at two distant shorelines, my mother facing the Mediterranean Sea in Croatia and me facing the Pacific Ocean in Sydney, our movements are repetitive and mirrored in one another.

Two ceramic cups I made for our ceremony were cast from my mother’s and my own clasped hands. In preparation for the performance, we exchanged our “hands” and they became ritualised “extensions of our bodily selves.”

The film starts with our hands telling the story. They are joined together against the black background. This is followed by the moment of our separation. As the screen splits in two, we each appear at different shorelines, facing the vast sea between us. The sound of the ocean is hypnotic and its roar slightly terrifying. It alternates and merges with the gentle and calming murmurings of the Mediterranean Sea.

The story continues to unravel through the entanglement of repetitive ritual movements, the shape of ceramic hands/cups, the warmth of tea warming our hands and its taste providing a comforting and familiar taste of home. All of these elements came together to trick our minds into a meditative state in which we felt in each other’s presence, sharing a cup of tea.

In a strange twist brought to life by this art ritual, when facing the seas which separate us and cradling each other’s ceramic hands, these cups, warmed by tea, evoked the warmth of each other’s touch. The ritual became a way of both confronting and overcoming our physical distance.

Our personal experiences in many ways correspond to the central function of the traditional Zen Buddhist tea ceremony. When making the ceramic hands/cups, I was strongly influenced by the haptic channoyu experiences that traditional tea practitioners talk about.

The sensation of handling a tea bowl filled with warm tea is amplified by the intrinsic features of a bowl. Ceramic bowls used for a tea ceremony are often under-fired as this makes them porous and conductive of body heat, as well as the temperature of the contained liquid. Our ceramic hands/cups were made in the same way.

A tea practitioner and artist Bonnie Kemske, who studied traditional tea ceremony in Kyoto, Japan, describes this sensation, explaining: “Cradling the tea-bowl is not just a function of the Tea Ceremony; it serves as a synecdoche for the Tea Ceremony itself. It is a deliberate and considered – imbued with consciousness, self-awareness, and shared action. It is the connection, tactile and spiritual, between you and the host, and the center of your own experience of this sensual art form.”

As I dwell on the subject of tea, on bonds between mothers and sons, mothers and daughters, a little poem comes to mind… My stepdaughter wrote it when she was seventeen years old, dedicating it to her grandmother. I kept it close ever since.

I offer it here as a summary from a child’s mouth, in all its simplicity and universal wisdom:

Tea

Would thee see

Sweet simple cup of tea

Saviour of all time.

Clasped in leather hands

Unwind.

About Alma Studholme

Alma Studholme is a Sydney-based Croatian Australian multidisciplinary artist working across ceramics, sculpture, installation, performance and video. She holds a doctoral degree in Arts and Social Sciences from the University of Sydney for her interdisciplinary research in cognitive sciences, neuroscience, contemplative religious traditions and art practice. Currently she is in her last year of completing a fine art doctoral specialisation in ceramics at the National Art School in Sydney. She is also a finalist of 2022 North Sydney Prize, which will be held in May. Visit www.almastudholme.com.

Alma Studholme is a Sydney-based Croatian Australian multidisciplinary artist working across ceramics, sculpture, installation, performance and video. She holds a doctoral degree in Arts and Social Sciences from the University of Sydney for her interdisciplinary research in cognitive sciences, neuroscience, contemplative religious traditions and art practice. Currently she is in her last year of completing a fine art doctoral specialisation in ceramics at the National Art School in Sydney. She is also a finalist of 2022 North Sydney Prize, which will be held in May. Visit www.almastudholme.com.