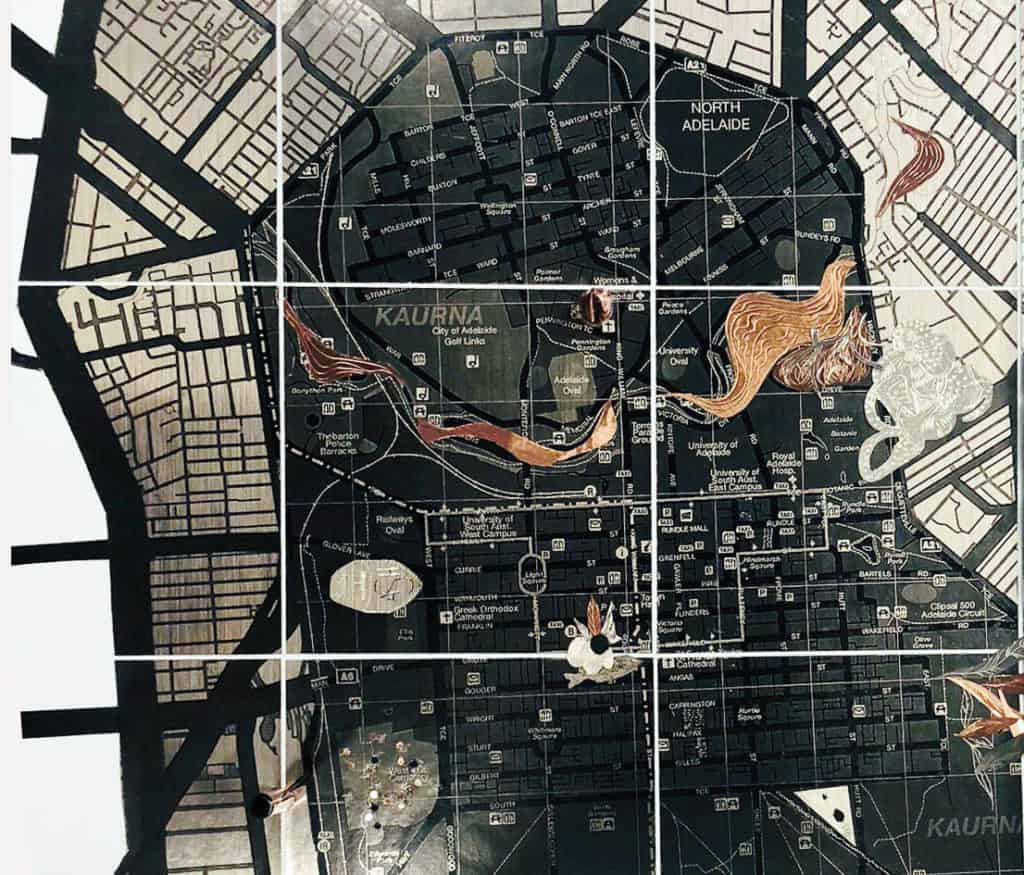

- Art Works Collective Project detailed view II, 2018, Metallic paper on board, Image Sahr Bashir

- Art Works Collective Project detailed view, 2018, Metallic paper on board, Image Guildhouse

- Participants working on Art Works Collective Project, Participants working on Art Works collective project, 2018, Metallic paper on board, Image Guildhouse

- Ela Samoraj, 2018, Metallic Paper, Approx 5×7 cm

- Jessica Stephens, 2018, Metallic Paper, Approx 5×6 cm each, Image courtesy Guildhouse

- Jessica Stephens, 2018, Metallic Paper, Approx 10×5 cm, Image Sahr Bashir

- Sonali Patel, 2018, Metallic Paper, Approx 6×8 cm, Image Sahr Bashir

- Sylvy Nguyen, 2018, Metallic Paper, Approx 3×10 cm, 5x10cm, 2x10cm each

Marcel Proust, the famous French novelist, in one of his most significant works In search of Lost Time said, “The real voyage of discovery consists in not seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes”.

Adapting to a new environment and culture can be both exciting and unsettling at the same time. As the transition begins, people, places and objects begin to offer comfort along the way transcending their physical forms to become an intrinsic part of a collage of new associations, meanings and memories. Park benches, corners and well-walked paths become trusted companions in the journey and familiar objects offer comfort in the search for a sense of belonging.

A longing for home can come in many shapes and forms: the fleeting patterns of light filtering through the curtains, the smell of jasmine, a bird song or a leafy tree offering refuge from the hot summer sun. In the face of a prolonged absence from friends, family and the familiar, my current state of displacement urged me to question the notions of ‘place’ and what lies within, between and beyond it. Seeking out familiar objects, sounds, smells and paths, I try and make connections with my new “home” as I come to terms with the change. For me, Adelaide was a challenge in every imaginable way, a gentle reminder at every step to take a pause and a deep breath, in sharp contrast to the vibrant but chaotic life I was living in the city of Lahore over the past four decades.

For an urban dweller like myself, the city features as the backdrop of life, a labyrinth of people, buildings, signs and lights. The Art Works project was initiated by the City of Adelaide in partnership with Guildhouse, previously known as the Craft Association of South Australia. The project sought to identify the diverse spectrum of experiences generated in response to the urban environment by examining the elements behind the key directions outlined in the City of Adelaide’s Strategic plan. Various artists were engaged to translate these core ideas into tangible realities by designing and developing interventions and workshops using different aspects of the city as inspiration. Focusing on an inherent understanding of jewellery as a symbol of personal expression, the conceptual framework underpinning my proposal of a Contemporary Paper Jewellery workshop as part of this initiative attempted to explore ideas to create personal objects in the context of a site or situation in the city of Adelaide.

Through an investigation of how the objects we acquire, carry with us or on us can help to create a sense of home, connectedness and belonging, the premise for this activity was to re-examine the relationship to a physical or emotional space through the process of site-based thinking. The exercise of toying with the very idea of “home” as a space shared by a multicultural population, a “place” which was a complex terrain of overlapping public and private domains served as a prompt for city residents to participate and respond to make both personal and shared thoughts portable by creating a personal wearable object and a collective piece.

The workshop urged participants to explore multiple starting points such as tracking frequently travelled routes on Google maps, identifying landmarks on the city map and rummaging and ruminating through the photos folder in their smartphones. A group of strangers to one another, we stumbled upon conversations centered not only around memories of particular connections or special moments, but also reflections on how our current understanding of ‘place’ relies on a sense of “space”, a social and cultural construct which demands constant negotiation between our identity and our environment, between the present, past and the future, the familiar and the unfamiliar. Fluid and in a state of constant change, it is our navigation through these intersections of composite elements that defines and challenges our notions of identity and sense of belonging to a particular place.

The site of the workshop itself was provoking, imbued with a historical essence. Built in 1939, the Minor Works Building was a two-storey structure in the heart of the city, which served as a mechanical workshop for the City Engineer’s Department. Interestingly enough, the original space, known as Sturt Street Depot, also housed a blacksmith’s shop, a storage yard, a weighbridge and a lethal chamber to “put down” stray dogs which were caught by the Corporation’s dogcatcher! Recently refurbished by the Adelaide City Council as part of the new housing development, it now serves as a community centre, a space for interaction, reflection and bonding for the community and surrounding residents.

Using all these ideas as a blueprint for contextualizing the ordinary or the memorable, participants were encouraged to build their unique narrative using metallic coated paper, a medium with qualities similar to copper or silver metal sheet used traditionally in jewellery and metalsmithing. Mark-making techniques like engraving and stamping offered an insight into the process of jewellery making to inform the objects in combination with paper construction methods which helped to translate ideas into three-dimensional forms.

The outcomes were diverse and varied, each object a carrier of unique experiences, associations and stories. Some connected to the city through silhouettes of the familiar evoked by memories of a particular experience at a given moment in time, while others commemorated or celebrated a specific site in the city which held significant value for them. For Sonali Patel, the swirling ocean and the “cotton wool” clouds represented a binding element in her concept of home. Yet others expressed their connection to the city in a more abstract manner resulting in a pattern of lines reflecting a wandering or a quiet meditation as could be observed in Sylvy Nguyen’s outcomes. A sensitive exploration of marks, textures and lines unite in Nguyen’s work to take the viewer on a journey through a landscape of evocative sentimentality. By manipulating the metallic paper to experiment with form, Jessica Stephens was inspired to push the boundaries beyond the flat surface of the medium to physically construct her connections to the city in material terms through her dynamic sculptural objects. A profound engagement was evident between each participant and the elements of their chosen place which depended upon more than the visual, a representation of the unseen and the unspoken. Each object, whether intimate or immersive, demonstrated a careful consideration of the elements and opened up onto the vistas of memory, contemplation and understanding.

The collective activity involved working on a large-scale map of the city printed on metallic paper. This served as a canvas for participants to leave their mark on the city by applying the same techniques learnt in the workshop, thereby personalising the map. Bridging their thoughts from their earlier wearable pieces, we contemplated the ways we shared the same space with others to become a part of the bigger picture. The River Torrens and the Parklands of the city came to life as a consequence of such interpretations through a gentle tracing of the contours of the riverbank flowing through the land and the symbolic offering of a pile of glistening metallic eucalyptus leaves. Iconic landmarks like the National Wine Centre, The Central Market and the West Terrace Cemetery rose up in all their glory from the interlocking grid of lines on the map, a testimony to the wealth of experiences the city has to offer to residents and visitors alike. A visual dialogue thus emerged out of this collaborative artwork, a narrative of overlapping routes and coincidental crossings of paths. Accompanying this deep sense of awareness was the realisation that our shared spaces are zones where time is deeply embedded within and across physical, emotional, intellectual, aesthetic, spiritual, social, cultural and geographical boundaries.

“Place” is more often sensed than understood. It has no fixed identity, indeed being more of an awareness than a clearly defined notion. A familiarity with space makes it into a “place”. For those of us who reside far from our homes, the objects we chose to create and surround ourselves with reflect our identities and sense of belonging. Paul Greenhalgh notes in the introductory chapter of his book The Persistence of Craft: The Applied Arts Today how “a space filled with such objects has the potential to become a place”. Even more poignant perhaps is his definition of crafts as being “portable places” and that how an engagement with craft practices is “literally to be touching history”. It is worth pondering upon then that the objects we cherish and hold dear to ourselves are not just mute artifacts that belong to us but to which we belong to. As embodiments of our personal and collective cultural legacies, objects and places form a significant part of the tapestry of our lives, weaving a unique pattern of memories, remembrances, identities and experiences beating to a rhythm of its own.

Author

Sahr Bashir is an art educator and a visual artist living and working between Pakistan and Australia. Through her teaching and art practice, Sahr seeks to explore the symbiotic relationship between the maker, wearer and the viewer in our everyday engagement with jewellery and objects. Her role as an Art Jewelry Forum Ambassador involves encouraging conversation on a global forum through training workshops, writing and collaboration. Her website is www.sahrbashir.com.

Sahr Bashir is an art educator and a visual artist living and working between Pakistan and Australia. Through her teaching and art practice, Sahr seeks to explore the symbiotic relationship between the maker, wearer and the viewer in our everyday engagement with jewellery and objects. Her role as an Art Jewelry Forum Ambassador involves encouraging conversation on a global forum through training workshops, writing and collaboration. Her website is www.sahrbashir.com.