- Elizabeth Shaw, Fixed dog, photo: Michelle Bowden

- Elizabeth Shaw, Rotary sickle, photo: Michelle Bowden

- Elizabeth Shaw, Repaired figure, photo: Michelle Bowden

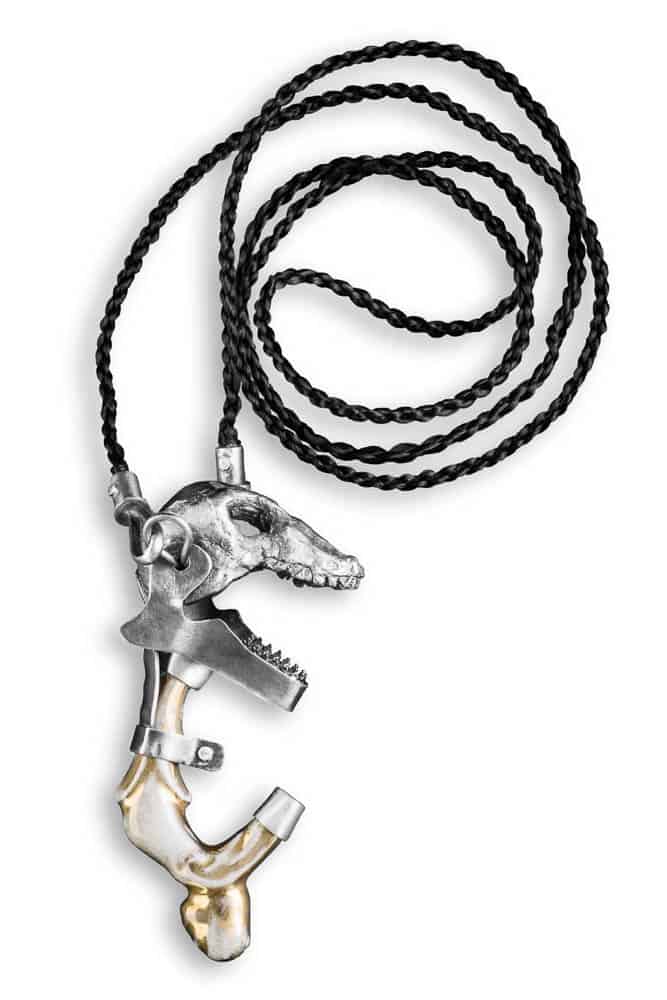

- Elizabeth Shaw, Caged arm, photo: Michelle Bowden

- Elizabeth Shaw, Bird of prey, photo: Michelle Bowden

Helen Wyatt caught up with Elizabeth Shaw to talk about her exhibition Recycled Narratives in Brisbane at Woolloongabba Art Gallery during March 2018.

Your current exhibition is called Recycled Narratives. Can you talk about the title?

The name came about from discussions with my colleague and PhD supervisor Debra Porch who is sadly no longer with us. In our conversations, she was struck by the strong sense of narrative across my work. It is not about a single narrative. It is really about materials that carry stories, mnemonic associations as well as objects that carry and evoke multiple narratives.

What is it about jewellery and small objects that attracts you?

I like the intimate scale and the connections jewellery has to humans and society. Recent studies have been pushing back the dates of earliest examples of jewellery. Some of these body ornaments are believed to have been made by Neanderthals who are now recognised to have been more intelligent than previously thought. The jewellery is being read as evidence of a sophisticated social structure.

I am also fascinated by portable objects—the fact that a traveller or refugee may take small precious things on their journey. These are items that are precious not necessarily because of their materiality, but due to associations. More often than not, this will be jewellery and that connects them to people and place. Jewellery and small objects are very real aids to memory.

Jewellery has such a close association with us as humans. It is a tactile relationship. For me, the work doesn’t have to be wearable so much as be something that is associated with the body, something that can be held in the hand.

Please talk about how your work has been evolving.

The works in this exhibition have been developed over the last seven years. While many have been exhibited elsewhere, this is the first time they have been shown together. They started with me thinking about mechanics and how society has been moving away from technologies that people could use and understand implicitly. Up until the 1970s things were fixable. That is no longer the case. We have moved away from knowing how things work in our houses and the simple mechanics that made this possible.

In Australia, we used to repair all sorts of things. Quite often these were practical, not aesthetic repairs. Even ceramics were sewn together with wire in some instances and they weren’t the beautiful Japanese Kintsugi repairs with gold!

There is an ethical dimension to this too, involving the relationship between the source of materials and the lack of transparency about how things are made. I have a very real commitment to ethical and sustainable practice.

These issues continue to play through in terms of my thinking. All my works draw on found and incomplete things, even the incomplete work of others that I have acquired, as well as discarded pieces of my own. Increasingly I have been finding more and more pieces as I walk the local streets and find broken things in the garden.

In April 2016 I was in London and contacted Steve Brooker from the BBC show Mud Men. The show’s focus is mudlarking along the Thames River. He took me out and showed me how to read the way the mud moves and where one might find things in response to the times and tides. He is very entertaining and it was an extraordinary experience. Things I found were imbued with much more historical significance because they were so much older than those things I collect in Australia. There are protocols for mudlarking—protocols for who can do it. There is licensing and there is a requirement to register finds of cultural and historical significance.

This was all so different from the surprising number of discarded mass produced objects that I find on my regular walks—things that have been dropped out of cars or run over. I do a lot of walking and I see what others don’t pay attention to. Sometimes items are very large and functional. For example, I even collected a bush saw. My real interest is the small and broken.

Is your later work significantly different and how has the exhibition been designed?

When I work I am generally still thinking about the last thing I’ve made while I am making the next thing. However, I am responding to a found item so the ideas that develop while working are influenced by it. The new works may end up drawing on ideas from much earlier works. The older pieces were quite often made from components found in my lemel, so they are quite often completely metal. Whereas the newer works feature more items found outside of my studio. Consequently, the exhibition is not chronological but rather it reflects the relationships I can see between the works. It is very useful to also have the eye of an external person looking at the work as a whole. My partner, painter Nick Ashby, has been able to see strong connections in groups of pieces and suggested the exhibition design. Jewellers tend to look at things so closely and I am in tune with the thing I am making/fixing and I do not always see a broader picture. Then the work becomes a physical thing in the world, separate from me and my studio.

I note that there is a “cabinet of curiosities” as part of the show. Please talk about those.

I was discovering or making a system out of my collection and this led to the “cabinet of curiosities”. For years I had been collecting things that seemed wearable. It was mostly metal and glass. These days, though, the collecting has expanded exponentially and has become more diverse. In general, though, the shapes and forms ultimately determined the organisation in this case. I was reflecting that before there was any scientific analysis or taxonomy, people observed how things fitted into nature and it was about drawing aesthetic relationships between things. Lots of people continue to do this intuitively.

I noted that Steve Brooker did that too when we sorted out the stuff collected from the Thames. It was interesting for me to see how he catalogued things. I observed, though, that the objects from the Thames had a really different materiality, so I separated them from the other finds in the display.

At the exhibition opening I was listening in to some conversations and people would say to each other “Ah yeah, … that’s what we should do with your stuff. So it is really all just about stuff!”

There are also works that are the result of collaborations with your partner Nick Ashby.

Nick is tuned into looking for things and has been walking, collecting and digging too. He is the one who found the small terracotta body under the concrete laundry washtub that became the diver in the necklace: the body had no head and feet and was so small, it would have been easy to miss. The plastic arm was turned up by an earth mover in our front yard and he spotted it. Collecting has informed his work and he has a collection of broken frames from glasses. He has been painting small portraits that fit where the lenses would have been.

We first collaborated for a show, the Miniature Museum, at Blindside Gallery in Melbourne 10 years ago. As Blindside alumni we were invited to exhibit in a show, Curtain Call in December 2016, so we chose to collaborate again. We used broken zingers we had been collecting. These are retractable identity card holders. Nick painted small portraits of Slavoj Zizek, Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss—authors whose books we were reading at the time: thinkers in the arts. The zingers are like office jewellery. I made small silver frames for the paintings to hang them where a worker’s ID image would normally be. These are a reference to the tradition of miniature paintings in jewellery, a form that often combined the skills of a jeweller and a painter.

What is your process? Is it initially conceptual, material or both and how do you develop it?

I very much respond to the environment and the “stuff” I find, rather than try to fit it to an idea or respond to the idea. With the rotary sickle pieces, I found small forged samples in my lemel. They looked like blades and took on a new life.

When I participated in the Contemporary Jewellery Exchange in 2016 I was paired with Molly Gabbard in USA. That exchange involved the paired artists finding a shared focus. We had much in common but her interest was very much in colour and all my work seemed to lack it. Fortunately, my chickens dug up some beaded red plastic which became the colour starting point for my piece for the exchange.

What is the role of the wearer and viewer in your work. Is it important that the work is worn?

Some of my work is not particularly wearable, for example, the rescued ducks and fixed dog. Some is specifically sculptural and not intended to be worn at all. You definitely wouldn’t do the washing up in the rings. They make a statement if worn rather like long fingernails do: I am not doing any physical work today.

For me, it is not essential that the objects are worn. Rather what is important is that they have a relationship to a human; that they are tactile things and that they have the capacity or potential for being worn if not actually worn. Some people love to try them on. They can sit in the hand. They are very small so they are human scale and can be held. They are things that are likely to be passed on by people and they are easy to distribute. They stand as a message or symbolise a relationship. My pieces all have elements that have associations with a prehistory; that allude to something before.

They work a little like folk stories do. The stories adapt to the culture they are in. The stories may be the same in essence, but differ in the time and the locations in which they are told. They move to different settings with different people. They incorporate new ideas and interpretations.

What I am thinking when making is not what I am thinking when they are finished as my ideas develop during the process. Meaning is not a finished thing. I enjoy responding to the found objects, how they feel and what ideas I get from them. As they evolve I respond to them as a whole and once they are out there the meaning changes again.

It is interesting when I see them all together. What does it say about how my brain works? For me, they are the continuation of a theme, but I don’t know what it is for everyone else.

Your work seems to have a medical edge?

For the Miniature Museum, I had made small limbs in calipers, but they were not consciously medical. I was using external frame works to support bent branches. They definitely ended up looking medical. They have been repaired a bit like building structuresm=, an engineering approach to fixing things. Metal bands hold the structures together and you see that in ancient structures where people have come along and enclosed an area of a structure with metal bars and big bolts.

Could you name an artist jeweler (or more) whose work you admire and who has significantly influenced your own?

As a young child, I visited the studio of Darani Lewers and Helge Larsen in Sydney, I recall being very impressed. I was intrigued by their tools and liked the feel of their workspace. Their use of materials and techniques, and regular exhibiting has contributed significantly to an Australian vernacular.

Merv Muhling was a Queensland artist who died in 2003. I inherited the contents of his workshop including his collection of found objects from his studio. Merv’s work often included found objects, my methodology is similar to his, but the aesthetic outcomes are quite different.

Don Ross is another Queensland jeweller, also deceased, whose narrative works enthralled me as a young child and continue to inspire me. Don was a dentist who taught himself jewellery techniques at a time when formal training was not available. He shared his skills generously. He had a good sense of humour that featured in his jewellery.

Muhling, Ross, Lewers and Larsen have been the primary influences for me, as I followed their works through my formative years.

Could you name one or two writers who have helped to clarify your thinking and impacted your practice? How?

Over time, the theorists who have influenced my thinking have changed a lot. Most recently I have been engaging with Vibrant Matter by Jane Bennet. She has an interesting take on thinking about the discards and materiality. Also Barbara Maria Stafford’s Echo Objects explores neurological science and its impact on how we view and understand objects and images.

Michael Crawford’s The Case for Working with your Hands deals with the satisfaction derived from manual work as opposed to screen based work. It addresses issues around transparency in manufacturing, as well as the devaluing of the labour and the value in the fixing or making of things.

Various essays and books by Richard Sennett have been influential in particular, The Craftsman.

What is next for you?

There are lots of things I am in the process of making or thinking through. Some of these are in the “cabinet of curiosities”. I have some brake and clutch handles from motorbikes I’d like to work with and I am tempted to use some bigger things. I also want to investigate more of Merv’s material that was not used. However, there is an inverse relationship between the rate of collecting and the rate of making!

I also have a thing with nails. They are ubiquitous and I have found them pretty much everywhere I have been, including Singapore one of the cleanest cities in the world, where litter doesn’t exist. Each nail is really different. Some are really old and some new; some have done nothing and some have been through fires or been torn out. The consistent thing is that they have been discarded. I could literally work on these forever, in that the supply appears endless.

Comments

Wonderful, insightful article, thank you Helen and Elizabeth.

Looking forward to more.