Surrounded by the sights, sounds and smells of saltwater and carved cliffs, the Er Pavilion rests lightly on the lawn by the J Shed – a gathering space for story, music, conversations, and performance for the three weeks of the Biennale. The Er Pavilion forms a new together-space, crafted from remnant timbers salvaged from the Fremantle Ports A Shed, anchored by limestone, and covered by a shimmering and woven ceiling – adorned with thread collected from Bathers Beach.

Atop the structure, a desalination system will siphon the surrounding salt water, with ngarngk (mother/sun) separating water and salt, so guests of the pavilion – plants, people, and the Walyalup keniny (winds) – can be replenished. Brendan Moore, Melissa Cameron, Syrinx Environmental, vittinoAshe, Er Pavilion, mixed materials, dimensions vary, photo: Rob Frith

Melissa Cameron writes about the making of the pavilion for the Fremantle Biennale, adorned with bangles of crowd-sourced beach debris, conveying a message of sustainability and reconciliation.

Early last year I was invited onto a large collaborative project to design a pavilion that would function as an ephemeral event space, for the Fremantle Biennale. The commissioned team for the Er Pavilion was architects Katherine Ashe and Marco Vittino, assisted by architecture graduate Daniel Colley, who make up the Perth firm of vittinoAshe (vA). As a conceptually driven practice, Katherine assembled a group of collaborators to establish the motive of the structure. The core team became Brendan Moore, former chair of the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council in Perth; Kathy Meney and Ljiljana Pantelic of Syrinx Environmental; and me, jeweller and interior architect.

We first assembled on a bright and hot January day for a site visit of Walyalup/Fremantle, led by the Fremantle Biennale team. They emphasised our site’s link to Wadjemup/Rottnest, and Brendan spoke of his ancestors’ travels there, via a land bridge that used to exist between coast and island in ancient times. The tour concluded at a small patch of grass, raised from the nearby ocean, and bordered by blue metal gravel, a triangle of sparsely vegetated garden, and a sandy beach path. This place, Mangaree, meaning meeting or trading place in Noongar, is now a small park. It would hold our temporary pavilion for the duration of the Biennale.

Katherine’s deep sensitivity to the area and knowledge of its recent architectural history was the background for our first big discussion, which wove in around a dozen participants. For this meeting, vA added representatives of the City of Fremantle, more of the Syrinx team and a former student of Katherine’s, Janine Moroney, who had researched Arthur Head, the post-colonial label of the location in Walyalup/Fremantle that would house the pavilion.

This discovery conversation encompassed a gentle kind of sifting and sorting, assembling impressions, facts and researched outcomes about the site. Through it, we traversed geological time, Noongar habitation and the earliest permanent structure of the Swan River Colony, through widespread settler occupation and the creation of the Port of Fremantle (which lies to the north of the site), through recent times to scheduled future changes.

Arthur Head is wedged between estuary and beach, with the Indian Ocean to the west, and the City of Fremantle east. The headland (and thus our site) has been gradually lowered in the last 200 years, in part as the earliest limestone quarry for the settlers of the 1830s. The lowering of our specific location has occurred since WWII. The site is bound by a road and adjoins the 100-year-old J Shed, currently housing artist studios. Behind the shed (to the east) is the cliff face left by the quarry, atop which sits the Round House, a former prison and the oldest colonial building still standing in Western Australia. Underneath this is the old whaling tunnel, a remnant of a longer tunnel that led through the cliff to what was once called Whalers Beach, now Bathers Beach. An assortment of heritage-listed buildings dot the bay to the south, which has hosted successive jetties. These have not always proved immune to the waves of rejuvenation that periodically strike the area.

Our visit, and our consequent discussion, was infused with salt. The salt in the breeze, the beach water, the sand, the limestone cliffs, and its force in shaping the estuary itself. The past and current local saltworks and refineries, and the just-a-bit-further down the coast desalination plant. Despite the rich layers of history on the site, salt’s influence over time was even greater than these Anthropocene changes. We resolved to work with, and against, salt.

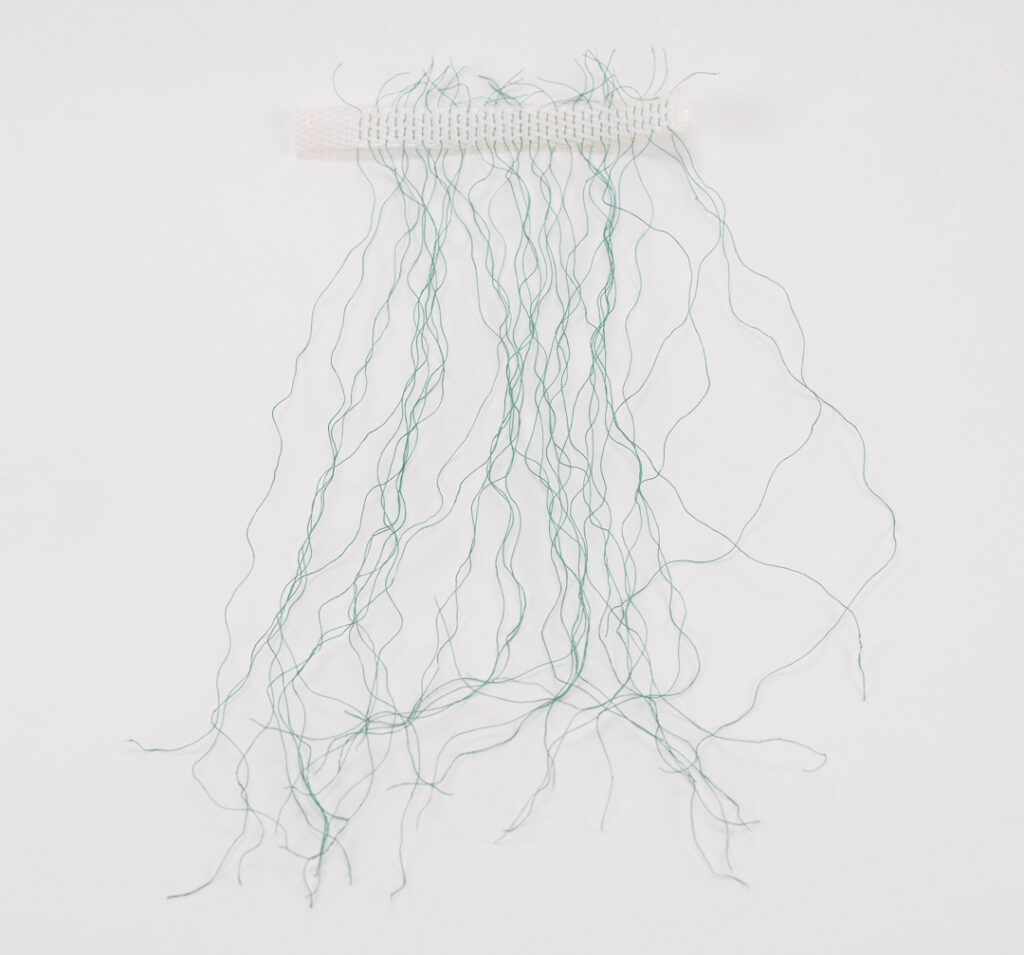

- Bruce Cooper, Courtenay Cameron and Katherine Ashe with hands of other volunteers working, Rapidly Closing Window 3 /Ngarngk WIP, 2023, found rope and waxed linen thread, dimensions vary photo: Melissa Cameron

- Piles of rope collected by Linda Davis, in Melissa Cameron’s studio. photo: Melissa Cameron

- Melissa Cameron with Brendan Moore, Rapidly Closing Window 3 /Ngarngk WIP, 2023, rope circles, found rope, dimensions vary, photo: Melissa Cameron

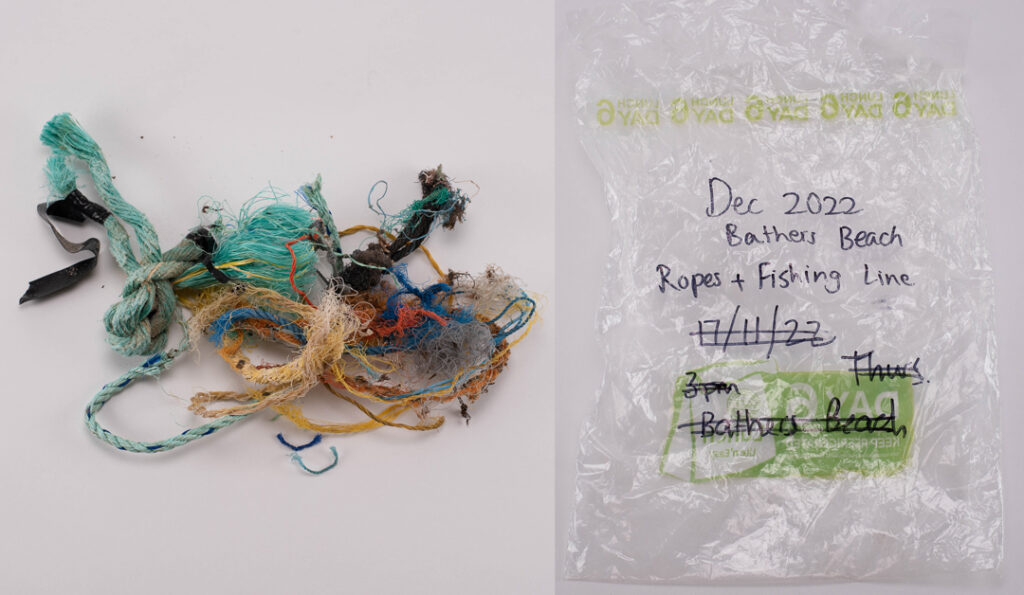

- found rope, 2022, plastic rope and fishing line (photgraphed 2023) dimensions variable photo: Mleissa Cameron

- Linda Davis’ Seahorse Bin on Bathers Beach, 2023 photo: Melissa Cameron

- sub-signal 1, 2023, found plastic strapping, found rope, 10cm x 20cm x 1cm photo: Melissa Cameron

- Melissa Cameron, sub-signal 2, 2023, found takeaway container lid, found rope, 8cm x 20cm x 1cm photo: Melissa Cameron

The saltwater and tides sent me material to investigate, in the form of discarded objects found on Bathers Beach. Collected by beach walkers, and offered up to science, they are left in a dedicated Seahorse Bin that has been a permanent resident of Bathers’ over the past year. Dr Linda Davis is a Notre Dame teacher and researcher, who created and now maintains the Seahorse. She empties and analyses the bin’s contents, gradually rehoming everything within, away from landfill. Several mounds of beach detritus thus collected allowed my creation of a set of small objects about our theme. These early investigations may not look related to the final work, but the experimentation to form them allowed me to feel for the boundaries of a material new to me.

As a jeweller, I adorn. My works pair this function with storytelling, communicating in visual languages. I use symbols and codes, floating messages on and within the adornments. In the gradual development of an adornment for this structure, we went through iterations that would be more and less disruptive to the other materials being used to define the space. Once the Pavilion design was formalised into a drawing by vA, I was given a space to embroider. At 4.5m across, epic by jewellery standards, I sensed a place for the most robust of the site’s found materials.

Fremantle is also a fishing port, so it was no surprise to find that rope was an abundant material collected at Bathers’. It was often short: a function, I learned, of boat propellers chopping it up. I could count on lengths of at least 30 cm, of varying diameter, hue, level of damage and plastic type. To make this a feature, I landed on creating small garland shapes, with the two ends heat-welded together to form a circle. I was to learn that not all plastic rope behaves the same when heated, still, welding was the most efficient way to create a robust and repeatable form. I modified pairs of slip-joint pliers and co-opted other jewellery tools to streamline the process. I made six hundred and seventy-five oversized polyethylene (and other plastic varietals) rope bangles, each with a join hardy enough to confront the Fremantle Doctor [the afternoon sea breeze] for three weeks.

With a base unit settled the design was roughed out. This determined that all the Bathers’ rope collected thus far would not be enough. We supplemented with more of Linda’s shoreline rope finds from the surrounding Walyalup beaches.

To speed up manufacture, a loose collective was assembled to grow the work, row by row. As a senior lecturer at Notre Dame University in the architecture program, Katherine connected me with a space, and Corine Van Hall from the Fremantle Biennale, a community, to complete the task. The individual bangles were laid out in colour order, an echo of the bicolour flags of semaphore signals, to reflect the 1s and 0s of a binary/ascii code. I learned, and then taught, a basic lashing, to which I added a knot. This process was repeated over, and over, to secure each circle to its mates, in sequence.

The lashing employed a waxed linen thread, robust yet slippery when it counted, from a 150m long spool that was kicking around my studio. I soon became aware of a worldwide shortage of that weight and colour, which sent me pinballing around the internet for a suitable replacement before that spool ran out. We went through roughly three more spools.

Melissa Cameron with Brendan Moore, Rapidly Closing Window 3 /Ngarngk as installed on the Er pavilion, 2023, found rope, waxed linen thread, fishing braid, stainless steel mesh, 4.5m x 1.50m x 30mm; photo: Melissa Cameron

In collaboration with Brendan Moore, affixed to the net, in a pixelated font of stainless-steel mesh circles (the same material as the Pavilion “ceiling” panels) and applied to the net using heavy fishing braid, is spelled the word Ngarngk, a Noongar word that means mother/sun apt for our coastal location, and a force which separates elements; water and salt. Its presence honours the site.

This principal and more readily legible sign overlays a binary code that I included in four separate works conceived in 2023. This time it was achieved by the colour order of the circles, with cream/natural/yellow rope representing 0s, and orange/blue/other colours representing 1s. (I snuck in a single black circle as the spaces between words, negating the need for seven more bits – characters – to represent those spaces. This saved making 91 more bangles.)

Decoded, this text reads:

rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable & sustainable future for all IPCC 2023

—

IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change. Part of C1, Headline Statements, 2023.

The finished work was affixed as a greeting to the Er Pavilion visitors, placed at the intersection of several pathways that led to the structure. The Pavilion itself was of an angle and scale that directly related to the J Shed and the cliff-face behind it, while addressing and adding to the garden that ringed the site. It was made from old, recycled timber from the nearby A-shed, which bore the markings of prior incarnations.

The roof structure was of a stainless-steel mesh, referencing the meshes used to literally sieve the salt from water in the saltworks and desalination plant. Atop each of the recycled timber ribs that held the mesh ceiling grid in place, was a desalination panel used to purify salty ocean water into drinking water. These were connected to a solar-driven system that allowed for a drum of fresh water to be gradually filled for use on-site. The grey drums held the water for purifying, as well as the pump.

The specificity of our message and our desire for a multi-layered repair of the site, informed by its history of use, helped vA shape the Pavilion. There were new plantings to tend, a no-cut rule on the timbers used for the supports (so their caretakers could guarantee future use), water collection and solar purification channels to be placed in the most beneficial locations, and the constraints of the mesh material used as shade ceiling that all had to be aesthetically aligned. Amongst competing aims and obligations, the adornment could have been lost. Instead, it became an invitation and a signal of welcome.

The process began with new collaborators and resulted in work made from a previously unfamiliar material. Not always a recipe for success. Yet by the time it came for me to start work in earnest, the messages, and their carrier, felt pre-ordained. My task then was to figure out how the pavilion could hold them, in a design able to be made with many hands. In the end, a net was the obvious answer.

Design team: Brendan Moore, Melissa Cameron, Syrinx Environmental, vittinoAshe. Structural Engineers: Forth Consulting. Industrial Engineers: Plan B Engineering. Builder: ICS Australia. Pavilion Sponsors: Alti Lighting, Archae-aus, City of Fremantle, F-Cubed, ICS Australia, Seahorse/Linda Davies, Sefar, Syrinx Environmental. Ongoing volunteer support: Notre Dame School of Architecture – Fremantle

About Melissa Cameron

I’m an Australian-born artist with Anglo-Celtic ancestry, living on Whadjuk Noongar boodjar. I spent close to seven years living in Seattle, on the Duwamish lands of Turtle Island/USA, but I’m now back in my hometown of Perth, WA. My practice is centred on my deep empathy towards our human bodies, and the narratives that link us, and is influenced by my background in interior architecture and my studies in computer science. I am preparing works for a solo show at PS Art Space in Walyalup/Fremantle in October, to coincide with the JMGA Conference and IOTA:24. Follow @melissacameronjeweller and visit melissacameron.net for further info, and to see my first permanent public artwork being installed in early 2024.

I’m an Australian-born artist with Anglo-Celtic ancestry, living on Whadjuk Noongar boodjar. I spent close to seven years living in Seattle, on the Duwamish lands of Turtle Island/USA, but I’m now back in my hometown of Perth, WA. My practice is centred on my deep empathy towards our human bodies, and the narratives that link us, and is influenced by my background in interior architecture and my studies in computer science. I am preparing works for a solo show at PS Art Space in Walyalup/Fremantle in October, to coincide with the JMGA Conference and IOTA:24. Follow @melissacameronjeweller and visit melissacameron.net for further info, and to see my first permanent public artwork being installed in early 2024.