Baluk Arts (VIC) is based in the Mornington Peninsula and represents Aboriginal artists from across Australia. While their origins are diverse their community is connected by common narratives of disconnection of family, language and country. In collaboration with Neil Aldum, a Perth-based artist, the artists have shaped a series of sculptures that speak of the connectedness of these upheavals and solace that comes from their shared experience – undulating and moving together with the changing physical and cultural landscape. Using ancient igneous rock as their counterweights each pendulum contains works that speak of their personal stories.

✿ How did the collaboration come about?

From the onset, In Cahoots has been led by the Aboriginal Art Centres, with their artists selecting and inviting an independent artist into their community to make a new body of work with them. Foundational to this process was the development of three-way agreements, with assistance from the Arts Law Centre of Australia. The agreements acknowledged Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property and ownership of the artwork and anticipated the expectations of the collaborating parties. Importantly, In Cahoots required the independent artists to make a minimum of two trips to the communities, allowing time to establish some mutual understanding and familiarity, before launching into the complex terrain of creative collaboration.

In Cahoots has engaged artists from every state and territory in Australia. The group is culturally diverse and boasts a raft of traditional and contemporary skills. The locations in which these residencies took places are separated by huge distances; from the Western Desert to Arnhem Land, to the Mornington Peninsula. The immediate overarching theme of the exhibition, collaboration, was quickly joined by a second, unanticipated, but equally important focus: sculpture, built from found materials and readymade objects. Artists in each of the six projects harvested materials directly from their surroundings, irrespective of their usual function or monetary value—discarded tin and plastic, native woods, rusted car wrecks, human hair, kelp, stones and desert grasses. The works capitalise on the form, colour and pliability of the materials, recombining them into forms with new meanings and significance. Through the exchange of skills and resourceful experimentation, each collaboration imagined a new life for the materials around them.

The Baluk exhibition evolved over two trips, with the final two focusing on producing works and getting documentation from the peninsula, i.e the video works of the community collecting stone.

Matching artists with remote/distant communities would always carry some risk. I feel this is what made In Cahoots and specifically the Baluk show so special—a gamble that paid off.

✿ What was the role of the external artist, Neil Aldum?

It was facilitated by Fremantle Art Centre’s project InCahoots, which was conceived almost three years before exhibition. In Cahoots was the brainchild of curator Erin Coates. It was an epic exhibition which celebrated cross-boundary collaborations.

According to the way the project was structured, Baluk Arts chose and invited Neil into their community. Neil facilitated a new way of making with Baluk artists. He showed a willingness to learn and share across cultures.

“Through exchanging ideas, skills and materials I believe projects like In Cahoots can create a special kind of dialogue between cultural communities. In my experience, the act of collaborative work tends to loosen up barriers and develop rich bonds between people and ways of working. After finishing my first visit to Baluk Arts, this project has already forced me to look at my practice anew—considering pace, dialogue and narrative in the development of a collaborative installation.” – Neil Aldum (InCahoots press release doc)

While the content of the exhibition was informed by all the artists, the overall direction of the show was largely driven by Dominic, Tallara, Lisa and myself. We formed a core working group to help shape the mood of the show, and refine how the pendulums would interact with the works.

As the exhibition text notes, the primary role of the artist was to bring potentially new approaches to making and showing work, however this work both ways, as myself and all the other artists grew immensely. Cross-cultural. collaborations like this have the power of creating lasting friendships and opening up dialogues that are unexpected and treasured, that was certainly the case for me.

✿ What was the brief for making the works?

The concept for the installation evolved over many months as the artists grappled with varying approaches of creating a visual landscape that spoke of both their diversity and their shared experience, and had a direct relationship with place. Many of the artists felt a deep connection to the sea, and the coastline that shaped their connection to country, spirituality and art practice. The basalt rock and the found natural materials from in and around the peninsula reference this common thread and compliment the artists’ diverse practices.

There were parameters set around the project, but not for the type of works and content. So there was no brief for the works as such, but rather the group of artists came to a premise themselves as the project progressed. The first visit involved a lot of brainstorming where we went through many ideas, then refined progressively with each site visit. It was challenging to come up with something that unified the diversity of approaches. We ended up working with very broad ideas and made the focus on making the connection between objects.

✿ Why was the rock used in the installation?

Early on in the planning of this installation, we established that we wanted our individual objects to sit on pendulums, and in order for the pendulum concept to work we needed a counterweight at the base. We wanted the counterweights to all be the same – to ground each of the objects in place and show a common thread. Held at the base of each pendulum was a rounded piece of basalt collected from the beaches of the Mornington Peninsula. At the end of the exhibition, the rock will be returned to country.

Basalt is an important material that pertains to creation stories on Bunurong/Boonwurrung country. Permission was granted by the local land council for us to collect and use this material. We used basalt as a material to connect each individual’s personal stories to one place – the peninsula. The collection process was documented via video and this was included in the installation.

Neil Aldum – Upheaval

Using cuttlebone and rubber, the work references my experience of listening and sharing time with Baluk artists as well as a continued interest in climate change adaptation. The cuttlefish (a cephalopod) uses its intricate and fragile bone to regulate buoyancy to navigate the waters. The prolonged process of collecting their bones along the WA coastline has been a comforting way of connecting with how Baluk artists interact with their Country. Similarly, the behaviour of the cuttlefish is a strong counterpoint to climate change where cephalopod populations will boom in warmer, more acidic water.

Kirsty Bell – ME

Kirsty Bell, ME, clay, acrylic paint, kelp, Sheoak, Tasmanian river reed, shell, emu feathers, resin, beeswax, cotton, linen thread, 66cm x 40cm x 14cm, photo: Fremantle Art Centre and Rebecca Mansell

Made of clay, kelp, sheoak, Tasmanian river reed, shell, emu feathers, resin, beeswax, and cotton, this work is the story of my emergence as an Aboriginal woman, the pain of broken songlines, and my journey of reconnecting with my culture. With each discipline I learn, it fills the void of disconnection from Country and Kin. The desert art on my torso represents my Ancestral Connection to the Arrernte people of the Central Desert. It shows my journey through life and the different directions I have taken. The kelp bodice signifies the importance of our Elders and their willingness to pass on traditional practices to the younger generations, which is vital to our survival. The weaving pays homage to the strong Aboriginal women who are the backbone of our communities – they inspire me to learn, share, and create each and every day. The shells, fibres, and feathers reiterate my deep connection to the land of Bunurong/Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation, the place I was born and raised and continue to call my home.

Dominic Bramall-White

- Dominic Bramall-White, North East Vessel (detail), 2017, Bull kelp, wood, Echidna quills, kelp, saddler’s string, hand- forged metal, 70 × 70 × 25 cm

- Dominic Bramall-White, Site Lines, 2017, wood, pyrography and hand- forged metal, 77 × 15 × 5 cm

This vessel speaks of the poetry between symbols and materials; it is formed from Hazel Pomaderris spars (a traditional spear making material), a black wattle hull, and bull kelp sails, which are balanced with a hand-forged whale harpoon. We all carry a vessel within. It is filled with intended and unintended cargo, to be called upon if required. Some are gifts, some things we pack ourselves and some are deep and part of the fabric of the ship. I hope to induce the feeling of vulnerable survival and surge forward. I wish to celebrate the deep, intelligent adaptation Indigenous Tasmanian people showed to the colonial reality and technology as well as my own and our own ongoing struggle with our new realities.

This swinging shield, balanced and centred by a rock from the places I grew up, talks of the balance we must make between what we expose and what we protect. Connection to Country has worked as a shield for many dislocated Indigenous people. I am a product of Western culture, a reclaimed Indigenous heritage and a story of dislocation through adoption. In my actions and happenstance there is a tension between white middle class education and a deep intellectual and instinctive association with my Indigenous genetic makeup. For me the symbols that are present in both ways are helpful to express this duality.

The Southern Cross is a shared symbol. A part of our land, sea and inner scapes, a cross for which the space between the lines represents my understanding of totemic, skin, flesh and spirit relationship with land and the crosses of Scotland and Ireland that are also part of my heritage. The imprint of Christian culture is part of colonial history and the colonial navy and later our colonised nation that co-opted this gathering of stars.

Glenn Forster – The Politician

Glenn Forster, The Politician, clay, resin, white enamel 30cm x 20cm x 20cm, photo: Fremantle Art Centre and Bo Wong

The figure, formed from clay and enamel, depicts a politician. He has no eyes because he only sees what he wants to see. He has no ears, because he only wants to hear how good his own ideas are. He has an open mouth to spout his rhetoric. The politician believes he knows what is right for our people.

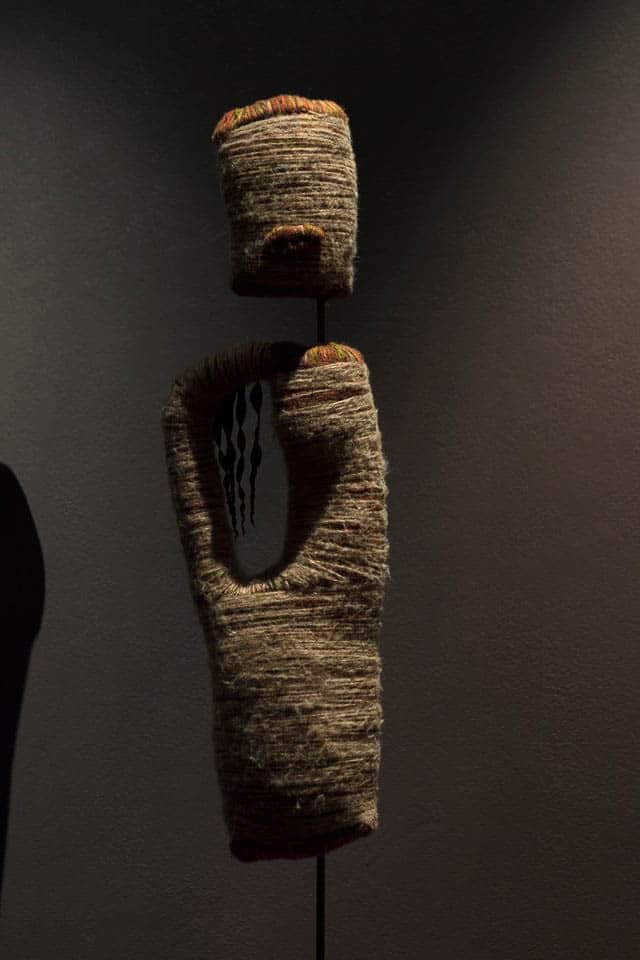

Gillian Garvie – Black on the Inside

The figure shaped from wool, hay and kelp shows a light wool exterior, however, hidden underneath it is encased in black wool – this represents my Aboriginal soul. No matter how much in my life I’ve tried to conform to the social constraints of judgemental and small- minded people I cannot deny my true self, which always reveals itself.

As a fair-skinned Aboriginal woman, I have received countless racist comments such as “you don’t LOOK Aboriginal”. I may have my grandmother’s fair English skin but on the inside where it matters, I am black. My soul is Aboriginal and when I die, I will return to my Aboriginal ancestors.

I have struggled with abuse and depression all my life, so even though my persona is that of a bright and bubbly person, underneath I am always also in pain. The empty cavity represents this hollow ache of loss, however the ever-present tug on my heartstrings remains – Country calling to me. A place where I can grow, bloom and love.

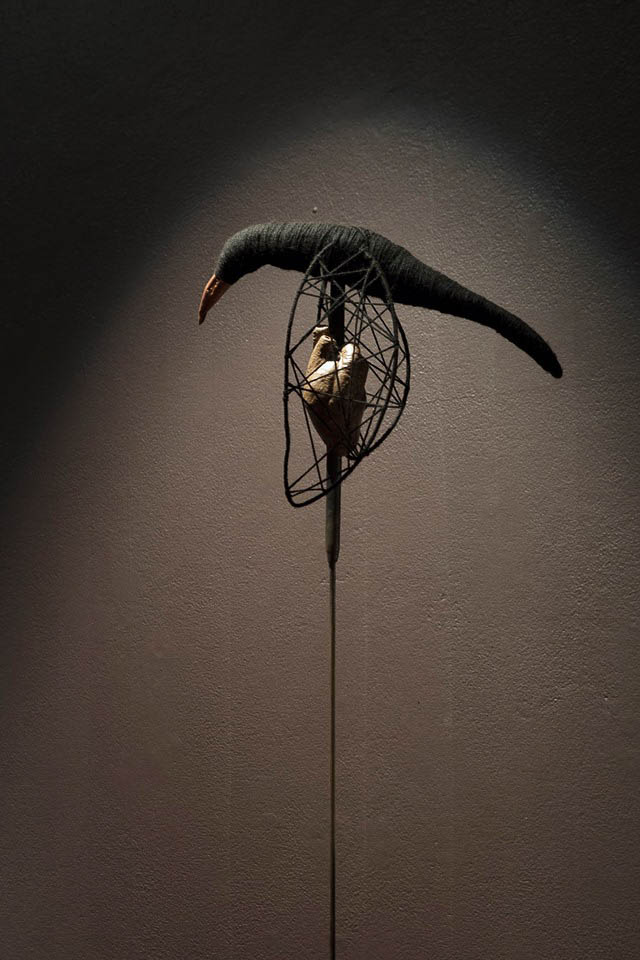

Gillian Garvie with her artwork Waa has my heart, 2017, oaten hay, wood, copper, wire, clay and resin, 32 × 42 × 17 cm, photo: Daryl Gordon

Waa Has My Heart Waa (the Crow) guides me and nurtures me to be the best me possible. He is a protector. He cradles my heart protectively and lovingly. The heart of clay represents my heart that is the earth of my Country. In this piece, made of oaten hay, wool, copper wire, wood, clay and resin, I’ve used the negative space in the wings to represent the complexity of identity and ‘looking through’ into what really lies beneath.

Tallara Gray

Family Tree is representative of family connections and the landscape. The shell, shaped from clay, is represented as an inverted family tree – each rung on the shell a generation and connection closer (or further away) from my Aboriginality, with me sitting at the tip. The crosses represent relationships with particular people in my family.

My Pa passed away while working on this project. He is the first Grandparent that I have lost, and the only one who connected to my Aboriginality. He had a very hard life and assimilated as a means of survival. Even then, his existence was a fight. The last 20 years of his life were his best and the grandchildren shared in this with him – exempt from the experiences of their parents.

Robert Kelly Law of the Land

Crafted from a single piece of native pine and local grass tree sap from the Mornington Peninsula, this shield is my depiction of protection of our culture and Country. My art is a vessel for me to connect with my culture – crafting traditional artefacts as they were made long ago. The pyrography details a main camp and its offshoots, with the central panel showing a men’s business area and the outer circular motif depicting women’s business areas. The outer linear design represents Country.

Rebecca Robinson

Rebecca Robinson, Fabric Midden, fabric, thread, Maireener shells, 130cm x 100cm x 40cm, photo: Fremantle Art Centre and Bo Wong

Using a piece of intangible landscape as inspiration, I wanted to create my own place of comfort. I don’t currently know of any particular midden in Tasmania that my family would have a direct connection to, instead of continuing to be upset about this I decided to make my own.

The oyster shell shapes represent my Indigenous family and my Dad’s ongoing connection to the sea as a place of healing and source of food. Since I was young I have always been fascinated with Maireener shells and understood their importance within Tasmanian Indigenous families. Sifting through the sands for these Maireener treasures is mesmerising, knowing the hands of my ancestors have done the same for hundreds of years before me. The stitching of my midden represents how I learned self- sufficiency, independence and pride from my Anglo grandmothers while developing my skills for making personal objects of beauty.

Living in Melbourne, being physically distant from my family and country, can be hard when I am depressed or grieving for family. The creation of my fabric midden has become a healing blanket for comfort and has given me a way to stay connected to life, to friends and to family.

Beverley Meldrum

Beverley Meldrum, Belonging, kelp, acrylic paint, oaten hay, wool, 180cm x 20cm x 20cm, Photo Credit: Fremantle Art Centre and Bo Wong

This piece, formed from kelp and wool, is a representation of me. I have a deep affinity with the dugong and salt water. In mythology, the dugong is represented as a mermaid and I have a strong connection to its presence. My family holidays consisted of times spent at the beach, camping on the dunes. The sea envelops my childhood memories, in particular the kelp – I recall smelling it rotting as a child and to this day the smell still brings me much comfort.

The dugong characterises my strength in life, while the ocean nurtures me with its many healing qualities. It is a source of food and a giver of life, which can be drawn on for strength in times of need.

Nannette Shaw

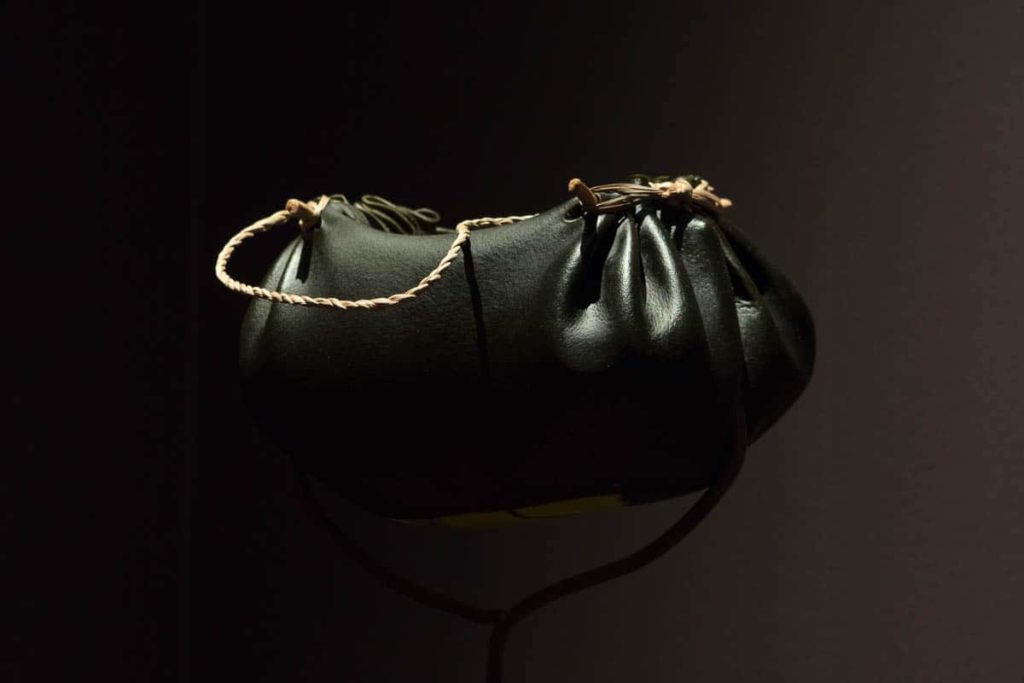

Nannette Shaw, Bull Kelp Water Vessel,bull kelp, river reed, tea tree, 20cm x 12cm x 14cm, photo: Fremantle Art Centre and Bo Wong

This water vessel represents the three family groups in Tasmania. The Bull Kelp was gathered on the north-west and represents the Dalrymple (Dolly) Briggs Johnson descendants. The Tea-Tree wood was gathered on the north- east and represents the Bass Strait Islanders (Tyereelore Island Women) descendants. And the river reed was gathered in the south and represents the descendants of Fanny Cochrane-Smith. The concept of making this is the same as it was by Tasmanian Aboriginal women in traditional days. The last traditional water carrier was made in 1851.

Douglas Smith Bundjil

Douglas Smith, Bundjil (Wedge-tailed eagle), cotton Rag paper, wool, cotton, locally sourced ochre, 60cm x 70cm x 20cm, photo: Fremantle Art Centre and Bo Wong

Using cotton rag paper, wool and ochre, I have created a soft sculpture of Bundjil – the great Creator spirit in South Eastern Australia. Bundjil created all living creatures and travels in the form of an eagle.

I created this work using ochres sourced with Traditional Owners from the Grampians and a three-layer stencil, a method taught to us by Melbourne street artists.

Lisa Waup – Finding Place

Lisa Waup, Finding Place, clay, ochre, enamel paint, cotton, shells, Coryus Skull, feathers, seeds, pine needles, pandanus, llama wool, 130cm x 100cm x 40cm, photo: Fremantle Art Centre and Bo Wong

I have created this work as a symbolic representation of my family groups coming together as a whole. The piece is made up of two separate ceramic spheres being stitched together to create an unbroken piece, encompassing the intricacies of balance in life. The open centre, delivering stability to the two family groups coming together, is me – I see myself as the join between the two and the light emanating from its connection. The bird skull found in the middle of the piece is again a symbolic representation of myself and my innate connection to birds and feathers in my practice. The earthy palette is a direct admiration and respect that I have with Country and nature.

Shane Wright – Rainbow Serpent

This work in timber honours and represents the Wanampi or Rainbow Serpent, a Creation Ancestor of Shane’s Country in northern South Australia. The rainbow serpent created all rivers, creeks and rockholes which formed paths of storylines which our people still travel and care for today. The Wanampi resides in a waterhole, is the keeper of the weather and carer of the environment. Shane was taught how to source timber, carve and burn designs to create snakes by the highly renowned Binbinga/Yanuwa artist Billy Cooley.

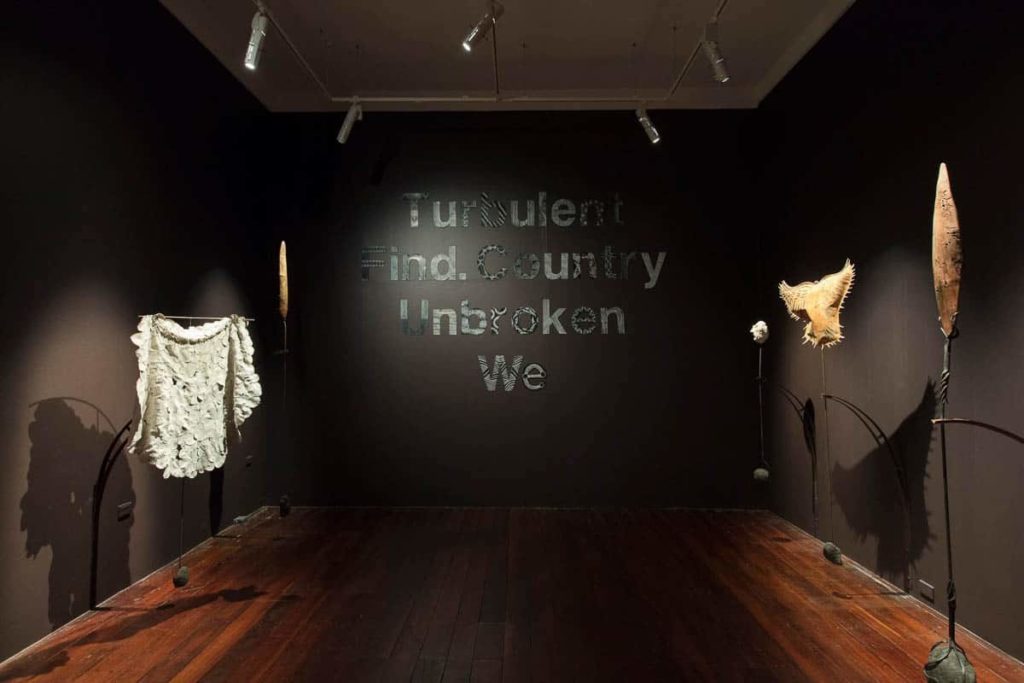

Neil Aldum, Tallara Gray and Lisa Waup – Together We Are

While the Mornington Peninsula is not the birthplace of all members of Baluk Arts, the connection and use of its elements and materials have helped shape their identification as Indigenous people. In collaboration with Neil, both Tallara and Lisa developed this text work to bind the installation and emphasise the collective experience of their community.

In Cohoots was an exhibition at Fremantle Arts Centre curated by Erin Coates, 25 November 2017 – 28 January 2018.

Authors

Tallara Gray is a descendant of the Gudang people of far north Cape York. Tallara grew up on Yuggera and Ugarapul country in South East Queensland, and has only recently moved to the Mornington Peninsula and joined the Baluk Arts team. She graduated from QUT with a Bachelor of visual art (fine art) Honors in 2015. Tallara has been and continues to be involved with Seed, Australia’s first Indigenous Youth Climate Action group, which has groups nationally.

Tallara Gray is a descendant of the Gudang people of far north Cape York. Tallara grew up on Yuggera and Ugarapul country in South East Queensland, and has only recently moved to the Mornington Peninsula and joined the Baluk Arts team. She graduated from QUT with a Bachelor of visual art (fine art) Honors in 2015. Tallara has been and continues to be involved with Seed, Australia’s first Indigenous Youth Climate Action group, which has groups nationally.

Perth artist Neil Aldum has a deep interest in both science and art, having held roles in the water industry and in climate change research. He works with predominantly raw industrial and agricultural materials, often using an unexpected combination of skills including weaving, woodworking, concrete casting and sewing. Neil has shown his work in numerous solo and group exhibitions across Australia and has received commissions from the City of Perth.

Perth artist Neil Aldum has a deep interest in both science and art, having held roles in the water industry and in climate change research. He works with predominantly raw industrial and agricultural materials, often using an unexpected combination of skills including weaving, woodworking, concrete casting and sewing. Neil has shown his work in numerous solo and group exhibitions across Australia and has received commissions from the City of Perth.