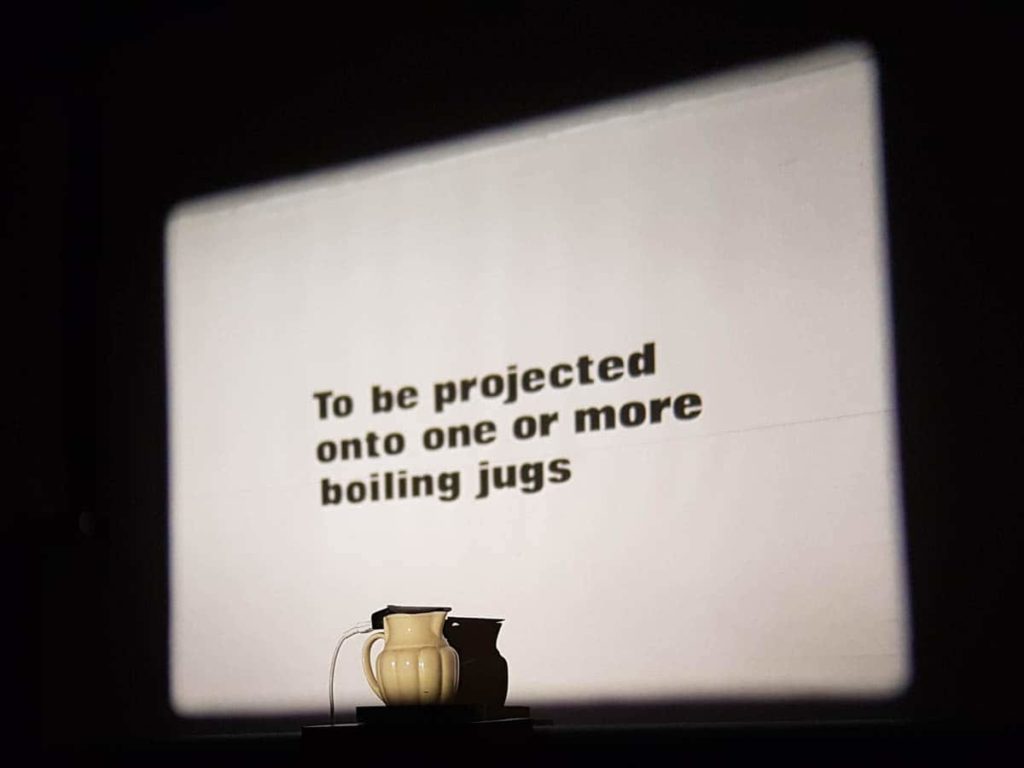

- Boiling Jug film with boiling jug

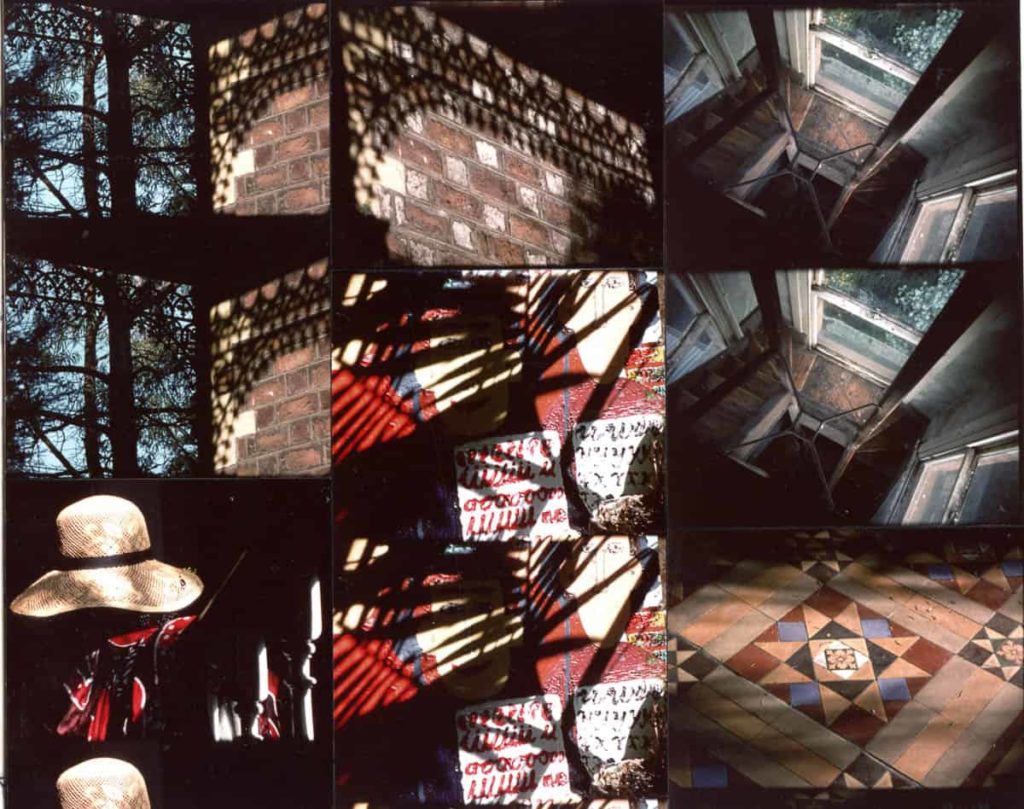

- Projected Light montage

- Ivor Cantrill pots

- Ivor Cantrill ceramic plate

Art and life are not distinct from one another in the house of the Cantrills. Is this why we make our pilgrimage out there on a monthly basis?

Meeting before noon on a Sunday at Southern Cross Station, to take the train to Castlemaine, there is never a flicker of doubt about the worth of partaking in the ceremonious screenings that Corinne and Arthur organise for a faithful and rotating audience. Throughout the voyage, as much as whilst watching their films (and sometimes those of their peers), and then during the sharing of a cup of tea and biscuits post-screening, as well as the meditative journey home, there is a percolating feeling that art is important again.

If we were to speculate about the source of this feeling, it would be simple enough to say it has to do with the density and intensity of being exposed to the Cantrills’ lifework: their love of Kodachrome, their sheer diligence, and their exhaustive, kinematic explorations. This and more inspires the persistent devotion of those of us who attend the Cantrills’ fleeting yet viscous screenings.

We say “viscous” because the images stick with us. And not just the images we see on the flickering screen, but the images that flash past from the window of the V-line train. Rolling hills and eucalypt forests repeat, cut, repeat, through the glass frame, like the Cantrills’ formalist essays of landscape, travel, country. There is a rhythm to this journey. When we arrive, we are often greeted by Ivor, Corinne and Arthur’s adult son, whose autism delightfully dispenses with formality. He cross-examines guests about their names, and whether they have just had a haircut or applied lipstick as he leads us down the long corridor where many of his own paintings hang: the Cantrills’ is a living museum, not just of the moving image, but of the painted portrait, still life and landscape. Ivor’s works amaze with their bold strokes, eye-popping palette and insistently repetitive subject matter. His rough ceramics decorate the garden and every spare surface in the house that isn’t already laden with papers or bowls of fruit.

We descend into the basement, which is like a kiva or sweatlodge: searing in the summer, and toasty with a roaring fire in winter. Corinne presides over everything like a high priestess in robes, brandishing a staff (walking stick) from her director’s chair in the centre of the room, while Arthur diligently proceeds with technicalities, showing great skill in manoeuvring the 16mm and 8mm projectors, often adding his own recorded compositions to the mix. Arthur has been recognised as an avant-garde sound artist in his own right; many of these works have been released on CD with Shame File Music. On special occasions, we are treated to “expanded cinema” experiences, like the steam from a kettle set up in front of the screen which intervenes in the image, live readings of text that accompany films, or live multi-media installations such as the phenomenal Projected Light – On the Beginning and End of Cinema from 1988, which involved intermixing slides with the projection and pre-recorded voice-overs: an extravaganza that had been assiduously rehearsed for two weeks. At other times, three projectors are set up side by side, screening the same image via three different coloured filters. The light beams are then superimposed to create a full-colour picture which pops right off the screen. These are just some of the examples of the commitment and superior experiments that the Cantrills make available to the curious.

Attendees are also part of the experience. Local artists, musicians and filmmakers, as well as those who make the journey from Melbourne, sit in a motley collection of seats, amazed by the Cantrills’ seemingly endless aesthetic and technical innovations on celluloid. John Flaus murmurs his appreciation in velvet tones, others clap and exclaim. When it is time for of tea, Ivor mans the teapots and wants to know exactly how many cups of Lapsang Souchong, or Japanese Green Tea you have drunk. We sit amongst biscuits and bowls of fruit, which vibrate with a post-cinematic energy. The quotidian is made extra-ordinary: like Kodachrome, which Corinne describes in Projected Light as being “more crimson, more viridian, more ochre, more violet, more black”, everything in the Cantrills’ world is in a state of glorious, rigorous excess. Here, then, is how a life is well lived—one must push the medium to its limits: be fiercely experimental, work incredibly hard, and sustain a radical attitude of love, dedication and attention to the present.

Authors

Tessa Laird is a New Zealand artist, writer, and lecturer, and recent arrival to Melbourne. Her book on colour, A Rainbow Reader, was published by Clouds in 2013. She is currently lecturing in Critical and Theoretical Studies at the School of Art, VCA, and writing a book about bats.

Tessa Laird is a New Zealand artist, writer, and lecturer, and recent arrival to Melbourne. Her book on colour, A Rainbow Reader, was published by Clouds in 2013. She is currently lecturing in Critical and Theoretical Studies at the School of Art, VCA, and writing a book about bats.

Camila Marambio is a private investigator, amateur dancer, permaculture enthusiast, and sporadic writer, but first and foremost, she is a curator and the founder/director of Ensayos, a nomadic interdisciplinary research program in Tierra del Fuego. Since moving to Melbourne, in February 2016, she has started to play the traditional flautón chino from the Andes Mountains she so loves.

Camila Marambio is a private investigator, amateur dancer, permaculture enthusiast, and sporadic writer, but first and foremost, she is a curator and the founder/director of Ensayos, a nomadic interdisciplinary research program in Tierra del Fuego. Since moving to Melbourne, in February 2016, she has started to play the traditional flautón chino from the Andes Mountains she so loves.

Comments

hi there, does one need to be invited to your screenings? I’m a chewton resident….. can I come?

kind regards brendan