Thinker-makers

Garland first five-year journey included essays commissioned from professional writers to explore in-depth a handmade object that helped understand the location of focus. This helped scope what was happening creatively across the Indo-Pacific region from the ground up. This has achieved a unique network of key writers and makers.

The challenge of the next phase is to bring this network together. Guided by responses to our survey, Garland 2.0 focuses on the questions that have arisen during this journey. The Thinker-Maker residency is a key part of this.

The Garland network includes practitioners with a university education. This is a unique generation that combines a skilled understanding of materials with formalised theoretical frameworks.

What is a thinker-maker?

Whenever the intellectual worker wishes to manifest his thoughts, he must use his hands and acquire manual skills just like any other worker. In other words, thinking and working are two different activities which never quite coincide; the thinker who wants the world to know the ‘content’ of his thoughts must first of all stop thinking and remember his thoughts. Remembrance in this, as in all other cases, prepares the intangible and the futile for their eventual materialization; it is the beginning of the work process, and like the craftsman’s consideration of the model which will guide his work, its most immaterial stage. The work itself then always requires some material upon which it will be performed and which through fabrication, the activity of homo faber, will be transformed into a worldly object. The specific work quality of intellectual work is no less due to the ‘work of our hands’ than any other kind of work.

Hannah Arendt The Human Condition

For Hannah Arendt, thinking is a form of making. We must forge our ideas in sentences that are assembled and bound into books. Since Plato, however, it has been assumed that these material expressions are unimportant, relative to the ideas they “embody”. The role of the thinker-maker takes this further by acknowledging the agency of materials and technique in the production of ideas. For instance, while books encourage linear thinking, objects allow alternative perspectives.

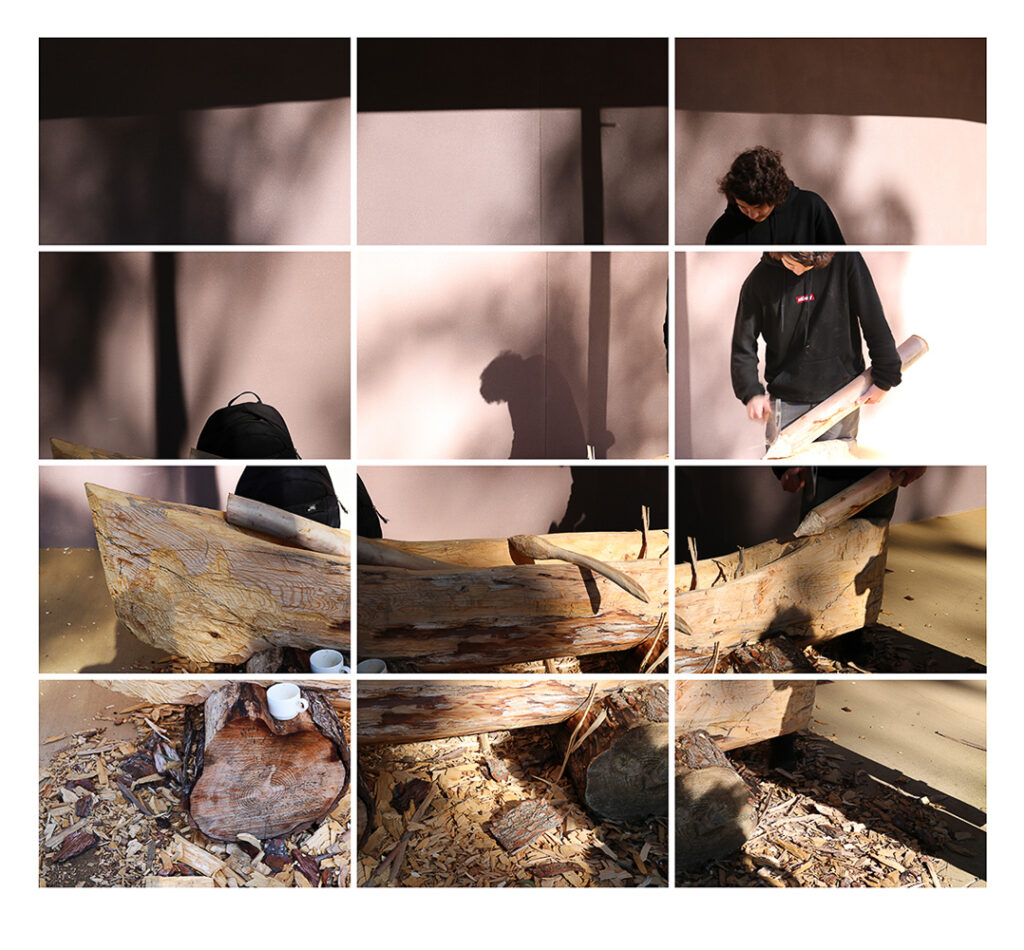

The thinker-maker is a person who creates knowledge with objects. Their engagement with materials helps answer a question. They employ the unique languages of substances such as clay, wood, glass or silver to develop an idea.

This thinking is not just conceptual. Thinking can be more than the play of abstract ideas. We need to test our thoughts. Ideas are not only tested in writing and argument. Their viability can be proved in the crafting process.

Thinking also involves commitment. The production of an object is a testament to the commitment to the value of materials and embodied time.

Objects reveal the world. What dimensions of “deep time” are revealed in the use of petrified wood? How does the layering of textile offer a model of settler-colonialism? Does a brooch that circulates between people help us conceive of alternative economies?

Currently, makers produce handcrafted goods that are sold in markets. Designer-makers produce original goods that can be made by others. The thinker-maker has emerged from a new generation of post-graduate craftspersons who are going back to the studio.

It should not be concluded that the thinker-maker is a superior version of the traditional craftsperson. It is an evolution that adapts to the knowledge economy. Those who work exclusively in production have a particular value in the development of skill and contribution to the product market. In the same way, the emergence of the “performance artist” does not imply any devaluation of those who call themselves just “artist”.

What kind of knowledge work is open to thinker-makers? There are academic positions, but they are rare and often precarious. There are less formalised spheres of independent work, such as writing, speaking, consulting and workshops. But there is also potential to open up new forms of practice, such as object commissions or online storytelling.

Thinker-maker residencies

The thinker-maker in Iranian contemporary craft - Narges Marandi, Atefe Mirsane, Farhang Parsikia and Zahra Mottaghi reflect on the changing meaning of "craft" in Iran.

The thinker-maker in Iranian contemporary craft - Narges Marandi, Atefe Mirsane, Farhang Parsikia and Zahra Mottaghi reflect on the changing meaning of "craft" in Iran. The bauxite challenge: Bioregional thinking and place-based making - Kyoko Hashimoto's place-based jewellery practice makes visible the hidden substances that fuel economic growth.

The bauxite challenge: Bioregional thinking and place-based making - Kyoko Hashimoto's place-based jewellery practice makes visible the hidden substances that fuel economic growth. Walking, thinking, making: A weaver in the world - Through six projects, weaver Sara Lindsay interlaces the warp of solitude with the weft of community.

Walking, thinking, making: A weaver in the world - Through six projects, weaver Sara Lindsay interlaces the warp of solitude with the weft of community. dhurrung wurruki nyayl ngarrp – kunang - Tammy Gilson reflects on the combined Wadawurrung connection to Country and English sense of industry that has shaped her artistic path and social leadership.

dhurrung wurruki nyayl ngarrp – kunang - Tammy Gilson reflects on the combined Wadawurrung connection to Country and English sense of industry that has shaped her artistic path and social leadership. On joining the NFT art mania: Creative liberation or lotacracy - Abdullah M.I. Syed registers a classic Pakistani object as a non-fungible token (NFT) only to re-affirm its value as a real tangible object.

On joining the NFT art mania: Creative liberation or lotacracy - Abdullah M.I. Syed registers a classic Pakistani object as a non-fungible token (NFT) only to re-affirm its value as a real tangible object.  The currency basket: Investing in a shared world - Bridget Kennedy creates alternative ways to exchange objects of value.

The currency basket: Investing in a shared world - Bridget Kennedy creates alternative ways to exchange objects of value. Remembering Kala Pani: Presencing memory objects - Arif Satar & Audrey Fernandes-Satar create objects of offerings for the lives displaced during the practice of indentured labour when the Indian Ocean was seen as a "British Lake".

Remembering Kala Pani: Presencing memory objects - Arif Satar & Audrey Fernandes-Satar create objects of offerings for the lives displaced during the practice of indentured labour when the Indian Ocean was seen as a "British Lake". Closing the circuit: Thinker-Maker residency at Substation 33 - Pamela See reports on her thinker-maker residence with Substation 33 where our recent technological past is repurposed for a better future.

Closing the circuit: Thinker-Maker residency at Substation 33 - Pamela See reports on her thinker-maker residence with Substation 33 where our recent technological past is repurposed for a better future.  Humans as a custodial species - Tyson Yunkaporta explains how humans became a custodial species and their role to increase the connections within the world.

Humans as a custodial species - Tyson Yunkaporta explains how humans became a custodial species and their role to increase the connections within the world.