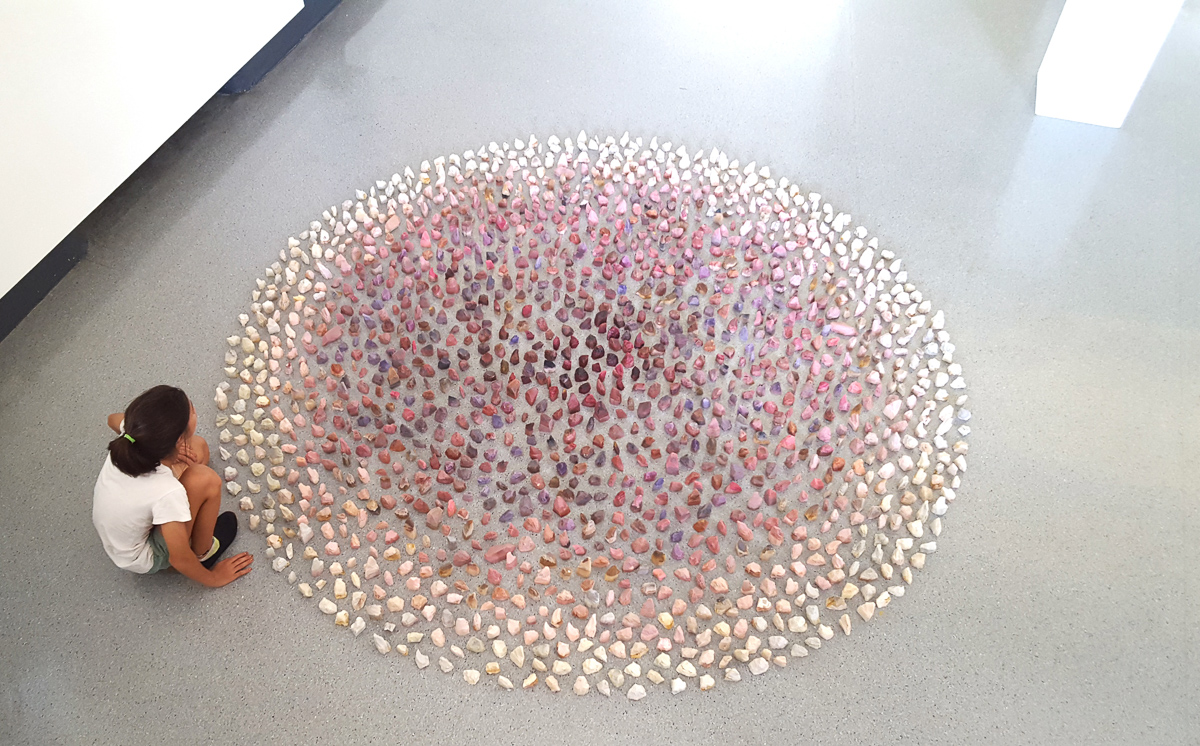

Bridget Kennedy, Just Help Yourself Why Don’tcha, 2013, beeswax, coal, silver, zinc, tin, lead, and gold, 2mx2m; photo: Luke Torrevillas

Bridget Kennedy reflects on a way of making that explores alternative ways of exchanging objects of value.

Can we redefine wealth and value? Can we subvert the traditional economic model and create new ways of transacting and redefining the value of things?

As a gallery owner and a maker, I sell things that I and others make, for money.

I used to think that running a gallery was separate from my exhibition practice but I have come to realise that it’s an integral aspect that has informed key areas of investigation within my work. The placement of my workshop within the public space has provided me with the opportunity to experience daily how people interact with objects. It’s allowed me to observe how value judgements are applied to the objects in the space differently. Sometimes it’s in the intrinsic “preciousness” of material, other times in the embedded sense of time, craftsmanship or artistic merit, or in the layers of meaning or associations attached to the object.

These interactions have resulted in an increased curiosity in exploring more deeply the potential for objects to mediate the intricate social relationships between makers, wearers, and audiences, and the perceived value of an object.

I started to explore these ideas with “Just help yourself why don’tcha” (2013), an installation of 10,000 beeswax ring elements containing coal, silver, zinc, tin, lead, and gold, all elements mined in Australia. Viewers were invited to select a ring for a nominal monetary exchange of $5 which was placed in an honesty box.

I was interested in observing how people would interact with the work: how the choice to souvenir an element of the work would change the whole. Where people placed value, over the perceived materials embedded in the beeswax, over the individual rings vs whole work. And whether they would consider walking on the work to get to the gold at the heart of the piece.

In the months that followed, anecdotes were received from people who’d seen others wearing the rings, and stories of what people had done with them. For example, one person had proposed with one of the rings, another had kept theirs in the fridge over a hot Sydney summer so it didn’t distort.

These stories increased my curiosity in understanding what happens to the object once it leaves the gallery/shop and enters the private sphere. How is it treated, where is it stored, what meanings are attached to it over time?

Bridget Kennedy, Choice Mate Site 2 installation, 2015, beeswax, pigments, found objects, pyrite, gold leaf, gold; photo: Luke Torrevillas

Choice Mate (2015-2017), explored these ideas further. Starting during an artist residency in Hill End, I made moulds of small rocks collected on walks across the local landscape that had been artificially created by people turning over the soil in search of treasure. The rocks were then cast in beeswax to create small wax effigies, incorporating local soil ochres, coloured pigments, small metal objects such as old buttons, bullet casings, and lumps of lead found left in small piles by current-day gold prospecting visitors, gold leaf, fools gold (pyrite), and an ounce of fine gold.

The idea was to build an artificial, miniature landscape as a kind of memorial to the historical past of Hill End’s natural environment. The microcosm was an invitation to consider the impact our interventions have on the larger physical environment. Each of the objects potentially contained some genuine gold. Visitors could decide to stake a claim and “mine” the work, souvenir and take a piece home. In doing this they left an indelible mark on the carefully constructed landscape, altering its original form. Or not. They could instead decide to leave the landscape intact.

The work was exhibited a number of times over two years, diminishing in size each time. This time, there was no expectation of financial exchange for the object. I was curious to understand how the work was valued outside of the usual currency exchange. However, participants who engaged with the work were asked to leave their contact details.

They were then contacted requesting an image of what they’d done with the souvenired object. Had they destroyed it in search of gold, kept it, passed it on? I also asked for some thoughts on the project. For me, this opportunity provided a richness and potential connection that a currency exchange could not. With each iteration of the project, a book was created containing the images and texts of the small social network created, as the original installation slowly disintegrated. The books were displayed upon a shelf, echoing the way in which many of the objects have been displayed in the private sphere. The social portrait thus feeds back into the artwork.

A third work, A Year of Time, and subsequent fourth work, Rethinking Value – the essence of time, delved even deeper and engaged with the relationship between participant-object and maker, on a more intimate level, whilst also exploring concepts of time, social, material and cultural values. It explored ideas of what our world might look like if money played a less central role in our lives. If the “share economy” of gifts and exchanges was utilised, what value could that bring to the experience of the work?

The installation of 60 small handheld woven basket-like objects, made over one calendar year in 2017 as a physical manifestation of the observation of the passing of one calendar year, scaled down to 1/30th, highlighted the labour of the handmade. A log of the minutes taken to produce each object was kept, and a small silver disc with these details was stamped and attached to each one. The individual objects could be “purchased” by exchanging in monetary currency, the number of minutes that the buyer considers their own time is worth, or by exchanging for time itself.

A currency basket is a financial term for a portfolio of selected currencies with different weightings.

Any monetary exchanges were converted into the currency of the Philippines, a country known for its cheap labour as well as basketry/weaving skills, and also a country with which I have personal associations. This hard currency was then woven into another vessel, titled Currency Basket (73 hours:49 minutes) and priced at the average Australian artist’s wage for the time worked. A currency basket is a financial term for a portfolio of selected currencies with different weightings. Commonly used to minimize the risk of currency inflations. In this case, it’s a mix of cold currency transactions handwoven into an object to minimise the risk of future financial hardship. Throughout 2018, 45 exchanges were negotiated, with 41 executed and all of the communication between myself, and the participant logged and documented on my website. On completion of the exchange, the participant received the object and a photo was taken of their hands holding it.

The exchanges that took place provided a richness to the transaction that cold currency just could not. It seemed that this type of transactional exchange, where the purchaser became “invested” in the transaction over time, added value to the crafted item itself creating memories of the connections made.

An abundance of goods and services were exchanged, including surfing lessons, gardening help, video making, website SEO, an essay, trip planning and home-cooked meals. One exchange, in particular, comes to mind. Laura chose ‘491:14730’ which she exchanged for 8hrs and 11mins of singing. She invited her partner and a percussionist to join her and between them, we held a “sing and soul” event at my home to raise funds for OzHarvest. I invited other people who were participating in the project, and another participant exchanged time making food for the event. It was a fabulous success. This morphing of one exchange into yet another community interaction just wouldn’t have happened if the usual cold currency exchange for the object had occurred.

Bridget Kennedy, Many Hands a year of exchanges and stories, 2018, mixed-media-wall-installation-2m-x-2m

The resulting exchanges and interactions, titled Rethinking Value – the essence of time, were exhibited at the end of 2018, alongside a work titled Many Hands: a year of exchanges and stories, which contained handwritten texts of each element of email communication of the exchanges.

There was a rawness and messiness to this project. When people become involved in an artwork it naturally humanises it and becomes more complex. There was often a richness and connectedness to community during the transactional aspect of these projects that wouldn’t occur when exchanging items for quick cash. These exchanges offered moments of deep connectedness often with complete strangers who may never have interacted with me in my regular day to day life. I brought people who were strangers into my home, I trusted them and they trusted me.

money offers a quick, cold transaction, that creates distance and can keep us separate, and sometimes this can be a relief

It was also occasionally frustrating, and these types of exchanges in themselves take time. Whilst the exchanges reduced the distance between the maker and the participant, money offers a quick, cold transaction, that creates distance and can keep us separate, and sometimes this can be a relief.

This can sometimes be a blessing, but at what cost? What could the world be like if money and the need to earn it played a less central role in our lives?

More recently, during Sydney’s 2021 lockdown, I experimented with an outdoor exchange bringing the gallery to the community. The change of context was challenging for people, and the weather brought yet another dimension. Sometimes four white walls can provide a comforting framework.

Related projects

About Bridget Kennedy

Bridget Kennedy is a contemporary artist, interested in finding creative ways to connect and build communities. She’s the instigator and co-founder of the Sydney Library of Things, Sydney Edible Garden Train and a founding member of Repair Cafe Sydney North. Visit bridgetkennedy.com.au, like facebook.com/bridgetkennedyprojectspace and follow @bridgetkennedy_projectspace

Bridget Kennedy is a contemporary artist, interested in finding creative ways to connect and build communities. She’s the instigator and co-founder of the Sydney Library of Things, Sydney Edible Garden Train and a founding member of Repair Cafe Sydney North. Visit bridgetkennedy.com.au, like facebook.com/bridgetkennedyprojectspace and follow @bridgetkennedy_projectspace

Comments

What a great group of exhibitions. If only people could take the time to really think about giving and what it means, this would be a greater world.

I especially appreciate here the opportunity to think about how the quick exchange of money (instead of something of ourselves) can feel so good to us. When I feel like this, what am I valuing?

Such an old concept re-investigated and enlivened through art making today. Beautiful!! Of course this sort of exchange does exist today. Have a look at various LETs systems (Barter systems) that are thriving in our communities. Those that are based on time are of particular interest to me because they “value” each other equally. And it is this “time value” that makes it so hard for people who work a 9-5 job to participate. It involves a lot of rethinking and evaluating of one’s lifestyle.

The other part of this thinking is the difficulty many of us have with receiving. In a true barter system, it doesn’t need to be a one on one transaction, but it becomes a circular economy. I give/make/do something for someone, this person can make/give/do something for someone else. It is truly based on circulation of trading/giving. It enriched everyone.

Thank you for your thoughtful comment Jasminka. The kind of communal reciprocity that you describe is ideal and reflected to a degree in the way people conduct themselves in well-functioning cities. The question is then whether a currency can help support this. Perhaps it can be a useful acknowledgment of its value.