(A message to the reader.)

Tammy Gilson reflects on the combined Wadawurrung connection to Country and English sense of industry that has shaped her artistic path and social leadership.

The thinker-maker for this issue is Wadawurrung ba-gurrk (woman) and elder, Tammy Gilson. Tammy’s life exemplifies the mixing of two worlds. Through her fibre skills and imagination, she has creatively reconnected with her First Nations culture. And in her public work, she has given voice for her people in how Country is sustained for the long-term benefit of all.

She has had a remarkable career so far. Tammy weaves traditional baskets, eel traps and adornments informed by her ancestral knowledge. In 2019, she won the RMIT emerging artist award for a woven basket of flowers at the Koorie Heritage Trust in Melbourne. Meanwhile, she is also a Cultural Firestick practitioner and works for the Victorian Government as the Aboriginal Partnerships Coordinator and Heritage Specialist. In 2021 she was Cultural Ambassador for the Victorian Nature Festival and a Cultural Advisor for the SBS mini-series, New Gold Mountain and currently Cultural Ambassador for Ballarat Foto Biennale and a creative of the Blak design program for the Koorie Heritage Trust 2022.

Today, Tammy lives on the Country of her ancestors: in Gordon, outside Ballarat, next to Kirrit Bareet (Black Hill). For Wadawurrung, Kirrit Bareet is a sacred place where the Bundjil the eagle initially created the Wadawurrung people.

Her path has been influenced by a powerful family. Her mother Marlene Gilson is a successful artist whose meticulous paintings subvert historical perspectives on colonisation. Her sister Dr Deanne combines visual arts with fashion design and her brother Barry is a prominent Wadawurrung singer and storyteller. In addition, Tammy’s journey as a weaver was inspired partly by spending time with two Aunties depicted in a book, Tayenebe, on Tasmanian Aboriginal women’s fibre work.

In this yarn, Tammy talks about the influences that shaped her journey and weaving practice. Her custodianship of Country through work and craft creates a powerful place for Wadawurrung alongside white Australia.

- Tammy Gilson (Wadawurrung), Karrap Karrap Binnak (Flower Basket), 2019, flax, echidna quills, hair, yellow ochre, gum nuts and sedge, 800 x 350 x 280mm; recipient of the Lendlease Reconciliation Award

- Tammy Gilson (Wadawurrung), Karrap Karrap Binnak (Flower Basket), 2019, detail

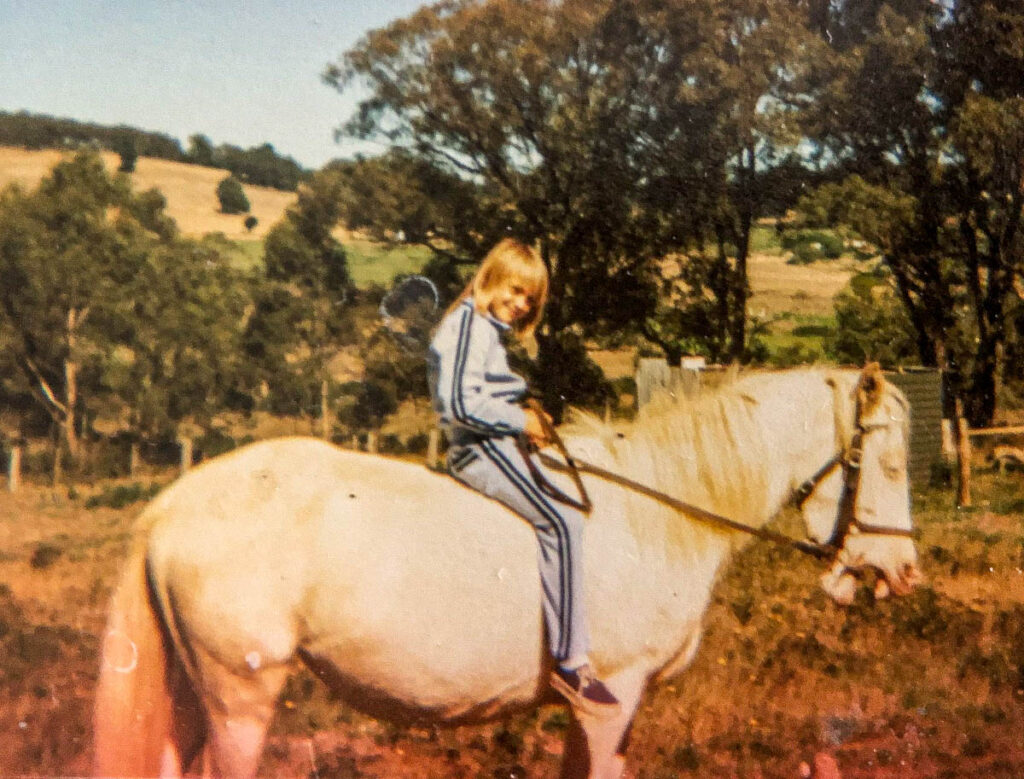

Where it began: growing up on horseback

I really embraced the outdoors: horse riding and growing up on motorbikes and going fishing with my brothers. I just really loved having a childhood in the country. There are not too many people that can say they rode their horse to primary school. The horse was named Dancer after a reindeer and was born just before my birthday on Christmas Day.

I spent my whole life riding through the bush here and connecting to Country. It was a really beautiful childhood. Back then we could ride anywhere as there were hardly any fences. We used to meet up, about 30 of us kids in town. We’d meet at the corner on horseback every night and just ride for hours.

I’d always pick up dead animals on the road and bury them. I’d collect feathers and forage in the bush. I’d be making mud pies and all those beautiful things kids did. In the end, all this play in the bush transformed into what I do now with my weaving practice.

We made the most of what we had. I used to make Christmas presents for everybody because I didn’t have much money. I also recycle things as well. I’ve made baskets out of plastic bags. I’m making a map on my floor at the moment from the kid’s old clothes. So everything has a purpose and we’re not wasting things

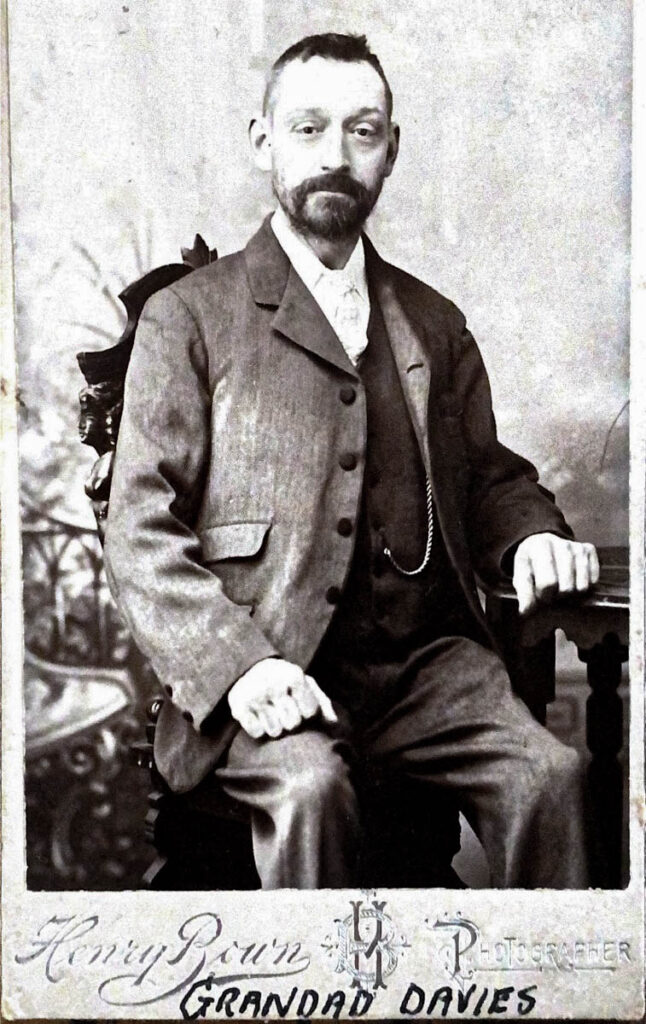

On the other side: English heritage

On my Dad’s side, my English grandparents were “ten-pound poms”. I love my English heritage. I have English cottage plants on my property here on one side and native plants on the other side. I’ve just acknowledged both sides of it because that’s who I am.

My great-great-grandfather was Welsh. He used to make baskets that he’d sell to buy food for his family. So I really love the idea that it’s not just a practice that comes from my Aboriginal ancestors but it’s also from my dad’s English and Welsh side of the family. It’s a beautiful connection.

We’re all very hard workers too. My dad never stops building. He’s 80 and building a studio room for Mum at the moment. I’ve always had that driving force of working. I guess, if you take that back to the ancestors, they also worked hard on Country, to live.

Sharing stories

Tanderrum has been very important to me. It is a significant Cultural ceremony that brings together the five Traditional Owner groups of the Kulin Nations performed in Melbourne for the opening of the International Arts Festival. I was chosen by the Elders to be the Wadawurrung dance leader for the event seven years prior to COVID.

We had dance practice every weekend for three months of the year and at least 120 dancers would perform at Tanderrum. We would go away with a big mob of us, sit with the Elders from other Countries and learn how to make and create our adornment so we could really celebrate Country when we dance. They all had a story, like the eel dance along the river where we took the kids to show them where the eel was caught. We translated that story to dance.

When you spend a lot of time out on Country, you begin to understand the landscape and feel the energy of the ancestors all around you. I feel them guiding me and presenting different things.

My cousin and I used to do something called “Yarns on Farms”. We would visit properties and take the farmer out and just walk with them all day on their property. And we’d uncover artefacts scattered around or scarred trees. We’d always smoke the area when we left to make sure that we weren’t taking home anything that we shouldn’t be taking home, like a bad spirit.

We belong to Country. It’s the humbleness towards caring for Country that I love. She provides for us and we look after her.

I was very pleased to get a commission recently to weave a healing mat for a local woman who is a descendant of the Cherokee people. I had a special interest in Cherokee as I used to always make leather teepees and collected Indian figures.

My brother and I had the same dream one night that the big Indian chief rode up on his horse where I live up on the hill overlooking Kirrit Bareet. He got off the horse and blessed me and my brother on the head. I always feel like I have an affiliation with them of some sort.

Favourite fibres

One of my favourite plants to weave from is New Zealand flax, because it’s long. Mum’s got a heap of it growing and if I see any on the roadsides, I’ll pull up and take some. But I always ask for permission and acknowledge the plant. I’d never take it from another country either as this is part of cultural respect that we don’t steal from others. We are always sourcing from what our own Country provides and although the New Zealand flax is not provenanced from Wadawurrung Country, it’s a good resource.

The grass tree is my favourite plant and I use the foliage for weaving filler when suitable. The grass tree is the most useful and oldest tree we use for Cultural fire practice. It contains resin used as strong glue when mixed with animal fur or kangaroo poo.

That’s what I’ll be incorporating into my jewellery design for The Blak Design Program along with the flower stalk which I used during a Cultural burn at Beremboke, better known as sister Country.

Cultural burning

I’ve been learning about Cultural burning since 2015 when I first travelled to Mary Valley Station on Awu-Laya Country, Cape York to learn about traditional fire land management practice that applies a cool slow burn methodology.

I became really invested in the women’s role in fire management as we burnt Country in areas only permitted by women. I recently supported and participated in two Aboriginal Woman’s fire workshops, one on Wadawurrung Country and the other on Truwana luna, Cape Barren Island, Tasmania. I have also participated in the virtual Firesticks conference 2020 panel discussion for women. The National Indigenous Fire Workshop is coming up in August and I am hoping to attend.

We need to burn areas to manage vegetation and for seeds to germinate. In one area the phalaris grass was so long that we tied it in knots to reduce the flare-up and contain the fire area. It was very time consuming but effective. It’s about reading the type of Country and applying the right fire.

The yellow-crested cockatoo is part of our Kulin fire story. We call it djirnap. The yellow crest on his head represents fire. There’s a bald patch underneath his crest and as the story goes the other birds fed him up and waited till he fell asleep and then stole the fire off his head and shared it amongst the people. And that is how we got our fire.

I also have an affiliation with the kangaroo. Whilst camping at the recent Women’s fire workshop I could hear shooter’s across the paddock and it sounded like they were trying to shoot them, I felt pain in my stomach and felt sick.

I make bone needles out of the leg bones to open up the holes for weaving to push the fibre through. But, of course, I only collect from ones that have passed from accidents

We are survivors

I was very fortunate in my childhood to embrace nature, but there was always that significant part that Nan didn’t really speak of and that was our Aboriginality. This is because of the way we were portrayed and treated as a lesser race of people. I used to get called names all the time on the school bus and I hated it.

Times are changing now, and I feel the old people’s spirit is stronger. We are survivors and always will be. What we need to remind people of is that my ancestors have been here for more than 80,000 years and colonisation has only been a few hundred years. We lived in harmony and the transfer of knowledge and culture was never lost, it was just sleeping.

dhurrung wurruki nyayl ngarrp – kunang

From the heart we speak, hear our voices and don’t be afraid.

About Tammy Gilson

Tammy Gilson is a Wadawurrung ba-gurrk (woman) who lives on Wadawurrung Country, which Tammy refers to as “Nan’s Country”. Tammy works as an Aboriginal Inclusion Coordinator for the Department of Environment Land Water and Planning (DELWP) in the Grampians region and has extensive knowledge of cultural heritage and natural resource management including traditional fire burning practice and mapping cultural values. Tammy is also studying a Graduate Diploma in Land and Sea Country Management at NIKERI, Deakin University. Tammy’s spiritual connection to her ancestors and country has guided her to revitalise and continue cultural practices today. Tammy is an award-winning fibre artist, in 2019 winning the RMIT emerging artist award for a woven flower basket at the Koorie Heritage Trust in Melbourne. Tammy has performed ceremony for Prince Edward, Bob Geldof, Xavier Rudd, Tanderrum and the AFL. Tammy is also the cultural ambassador for the Victorian Nature Festival, Ballarat Foto Biennale, and a Cultural Advisor for SBS mini-series, New Gold Mountain. Visit www.yarroweeculture.com.au and follow @tammy.gilson.52

Tammy Gilson is a Wadawurrung ba-gurrk (woman) who lives on Wadawurrung Country, which Tammy refers to as “Nan’s Country”. Tammy works as an Aboriginal Inclusion Coordinator for the Department of Environment Land Water and Planning (DELWP) in the Grampians region and has extensive knowledge of cultural heritage and natural resource management including traditional fire burning practice and mapping cultural values. Tammy is also studying a Graduate Diploma in Land and Sea Country Management at NIKERI, Deakin University. Tammy’s spiritual connection to her ancestors and country has guided her to revitalise and continue cultural practices today. Tammy is an award-winning fibre artist, in 2019 winning the RMIT emerging artist award for a woven flower basket at the Koorie Heritage Trust in Melbourne. Tammy has performed ceremony for Prince Edward, Bob Geldof, Xavier Rudd, Tanderrum and the AFL. Tammy is also the cultural ambassador for the Victorian Nature Festival, Ballarat Foto Biennale, and a Cultural Advisor for SBS mini-series, New Gold Mountain. Visit www.yarroweeculture.com.au and follow @tammy.gilson.52

Comments

Thanks Tammy for this article, what an amazing collection of such diverse knowledges you bring together so beautifully.

1-“I also have an affiliation with the kangaroo. Whilst camping at the recent Women’s fire workshop I could hear shooter’s across the paddock and it sounded like they were trying to shoot them, I felt pain in my stomach and felt sick”.

2-“This is because of the way we were portrayed and treated as a lesser race of people”.

These two sentences describing the virtues of being human… A very good explanation…

I wish you long life with good health, Blue planet needs guardian spirits…