Harpreet Padam with Iqbal Hussein Wani – Conversations Collection – Box Sets

Harpreet Padam ventures to Kashmir for craft development, but finds the conflict difficult to ignore. He works with local artisans to develop papier maché objects that reflect their daily life.

In September 2017, I was fortunate to be selected as one amongst five designers to work with twenty-five craftspeople in the Srinagar region of the Kashmir valley. The project, named Kashmiriyat was initiated by the Commitment to Kashmir Trust, in partnership with Dastkar and with a funding grant from The Titan Company. The designers for this two-year product design and development project were selected on the basis of their prior experience in the Indian crafts sector. My own work experience in craft, till then, had been with Dhokra metalware, Bidriware, Channapatna lacquerware, and Banaras woodturning.

Apart from design and development of a product range that would be marketed with support from the Commitment to Kashmir Trust, one of the main project objectives was to instil in the artisan, the confidence to operate as an independent entrepreneur. The Craft Development Institute, Srinagar, already runs academic programs and initiatives towards this end and was a natural partner to the project.

Of the four crafts and associated artisans linked with me, I was most excited about working with the papier maché communities: the Sakhtasaaz shape and mould the raw paper pulp into various forms and the Naqqash finish and paint upon these forms.

Over the course of two years between 2017 and 2019, I visited Kashmir five times, staying for approximately a fortnight on each visit. For each such trip, all designers, including the project team and mentors, coordinated their dates so we could all gain from the collective energy that a team brings. This prolonged mingling and interaction with the artisans allowed for product development to get the time it deserves. More importantly, though, the time allowed me to gain first-hand experience of viewing life in the troubled valley. In the first three visits, I made it a point to visit and see the homes and workplaces of even the artisans who were not assigned to work with me. Conversations with them and their families, over salted Kashmiri tea and the typical Czot bread would range from pleasant exchanges to frequent expressions of frustration over the never-ending state of affairs in a city and state they love dearly.

In the markets, streets and lanes, it was hard to ignore the painted wall graffiti announcing India as the oppressor—demanding an end to the occupation of Kashmir by Indian security forces. On my first visit, I was taken aback initially by the way many Kashmiris referred to India as a separate entity: they hinted that visitors from India were foreigners. It took time to get accustomed to it, but this way of referring to Indian occurred often.

Frankly, it’s not too difficult to feel the same way if one imagines how the continued violence has taken a toll on even simple aspects of Kashmiri life, like walking by the road, meeting a group of friends or even planning ahead for the day after. As one of the other designers realized when a Kashmiri craftswoman visited her later in Bangalore—the fact that there were no security forces, cordons, or barricades on the streets of Bangalore was an unsettling and almost new thought for her. Perhaps we don’t think about this freedom in our lives, till we encounter an account of its absence in another place.

On a sourcing trip one afternoon to a market in downtown Srinagar, I was on a motorcycle with an artisan when we happened to drive into a neighbourhood that was on the verge of an altercation between Kashmiri boys and the Indian security force. Doors and windows were ominously shut and an eerie silence clouded the street. Shadowed behind a wall was an armoured jeep and soldiers, their faces unable to conceal their nervousness. I happened to notice one of them had his hand clenched upon a tear gas canister, ready in every way to toss it if needed. We fled. Such incidents are common in Kashmir. Perhaps nothing happened that afternoon, but a lot more does, every single day.

When it came to actually designing a range of products with the papier maché Naqqash craftspeople, I could not ignore these sights, conversations, incidents and the feelings that had crept into me over this period of time. Together with the papier maché fine artist Iqbal Hussein Wani, we eventually agreed that our co-developed product range would portray the craftsman’s perspective of the situation. A protest typical to the craftsman’s non-violent nature—patient, observant and poetic, yet potent.

The first range I designed was a set of stationery boxes based upon three sets of thoughts I had gathered from conversations with locals. I named them A Fence in my Garden, Instead of Apples and If I lose my Way.

Harpreet Padam with Iqbal Hussein Wani – A Fence in my Garden 2019 – Handpainted Himalayan fir wood 63 mm x 203 mm x 40 mm

One half of the A Fence in my Garden box features a bunch of flowers (an omnipresent feature in the decorative crafts from Kashmir) while the other half features a motif of barbed/razor wire, similar to the one used by security forces across Kashmir. This razor wire pattern is in a raised relief effect, for which the artisan’s skills are quite well known in his community. The idea behind this box and its theme has been to subtly communicate the artisan’s displeasure at the presence of security forces and barricades in every Kashmiri neighbourhood. In one conversation, I remember somebody remarked that even little kids in Kashmir knew what razor wire was and what it meant.

Harpreet Padam with Iqbal Hussein Wani – Instead of Apples 2019 – Handpainted Himalayan fir wood 63 mm x 203 mm x 40 mm

The Instead of Apples box depicts a luscious red apple flanked with stones, just like the ones used in street protests by young Kashmiris against Indian security forces. Again, the texture and appearance of the apple and the stones is pronounced by the relief work skills of the artisan. The idea behind this theme is to subtly communicate the artisan’s ironic comparison between what Kashmir was known for earlier and what it is known for now. He had once asked me – “Do you know what Kashmir was best known for earlier? Our apples and orchards. And do you know what it is known for now – stone pelters.”

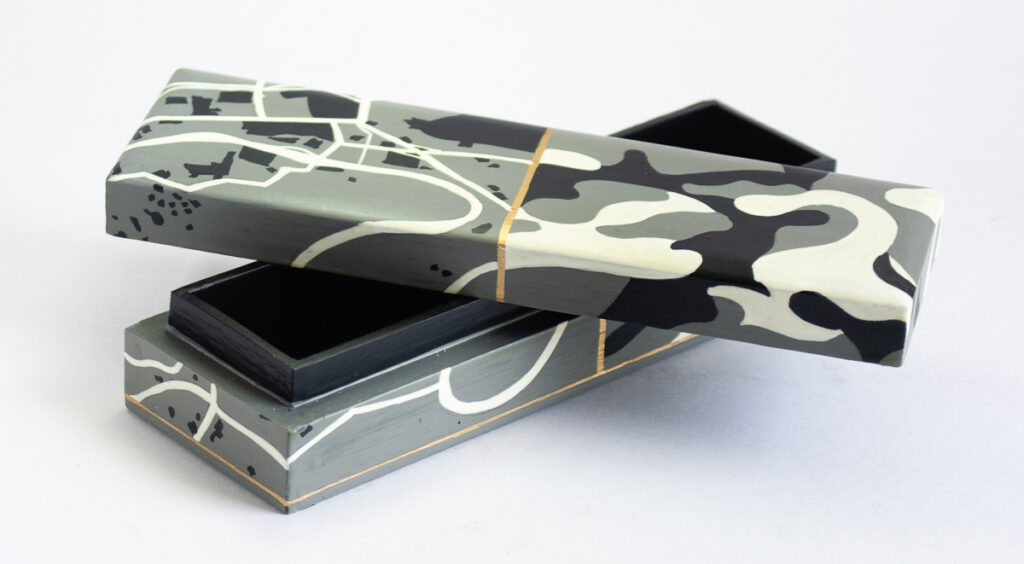

Harpreet Padam with Iqbal Hussein Wani – If I Lose my Way 2019 – Handpainted Himalayan fir wood 63 mm x 203 mm x 40 mm

In the third box, If I Lose my Way, one half of the box depicts a map of Srinagar city while the other half depicts the distinct camouflage pattern used and worn by Indian security forces. The two halves are separated by a thick golden line. The idea for this box developed over a conversation with a local Kashmiri family, when a lady mentioned that the neighbourhood she remembers from her childhood had changed so much that the security forces were now an inseparable part of it. As if it was now home for them as well.

Towards the end of the workshop, while reading more about the nature of protests across the world, I came upon the work of the American songwriter and singer Phil Ochs, whose words really resonated with what I had often begun to feel about the state of art and craft in Kashmir. Phil had opposed the Vietnam war and his songs became anthems of protest amongst his followers. One such song had the words, “In such ugly times.. the only true protest is beauty”. I thought this was exactly the way an artisan, a craftsman protests – by continuing to work and produce objects of beauty even within the harshest of situations in his society, neighbourhood and land. What he feels is no less than anyone else, yet the craftsman is likely to be of calm demeanour. He may not go out on the street to protest violently (even though there may be instances of such in Kashmir), but he does carry within him the want to express his frustration in his own familiar way. And his way is his work.

Inspired by these thoughts, I worked upon designing a set of coasters carrying the words of the song by Phil Ochs. Though not using actual words but braille. The association and idea of using Braille were influenced by having constantly seen news reports of local people injured and blinded by pellet guns. The coasters themselves were a familiar product that the Naqqashi artisans have been producing since decades. Also, Iqbal Hussein Wani’s skill with working on relief patterns suited braille very well.

Harpreet Padam with Iqbal Hussein Wani – True Protest Collection Coasters Set 2019 – Handpainted Himalayan fir wood 115 mm x 115 mm x 33 mm

In the summer of 2019, a little after we finished prototyping these products, Kashmir was closed to all visitors by the orders of the Indian government. Phone communication was cut, reporting was limited and the artisans were clueless about what would happen next. After about four months, when communication was partly restored, the Commitment to Kashmir Trust managed to organise an exhibition of all the developed products at the Bangalore International Centre in Bangalore. These products that I developed with Iqbal Hussein Wani were also part of the exhibition and were met with much appreciation from visitors.

At present, the Commitment to Kashmir Trust, via their new sales arm Zaina by CtoK is now establishing a website to market the range.

Author

Harpreet Padam received a BDes in Accessory Design from the National Institute of Fashion Technology, New Delhi in 1999. After working for six years as Head of Design at the jewellery brand Carbon Accessories, he started his own studio Unlike Design Co. with partner Lavanya Asthana, a communication designer from the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad.

The studio provides design services in graphic and accessory design to the home, fashion & lifestyle industries and has exhibited at the Milan Furniture Fair, the Salone Internazionale del Mobile, in 2013, 2014 and 2017. Harpreet was a winner of the Elle Deco International Design Award 2018 in the tableware category for his work in Bidriware. In 2019, he won the same award in the Kitchenware category for his work with the papier maché artisans of Kashmir. In 2020, the Petal Collection of Teascoops developed in the craft of Udayagiri Wooden Cutlery won him a shortlist in the Lexus Design Award India in the craft category. Most objects developed in his craft projects can be found at the studio’s online brand TOWITHFROM.