- Alipur village

- Basketry

- Craft centre, Alipur

- Laptop cover

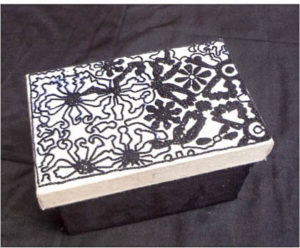

- Storage box with traditional embroidery

The sounds of singing and clapping echo in the dusty courtyard of a modest mud house amidst patchy green fields in a village caught between the Jhelum and the Chenab, two of the five rivers that lend their name to the fertile province of Punjab. Sitting cross-legged on a simple woven straw mat, a group of twenty-five women, some with their young toddlers, share a moment of joy in celebration of the return of the jailed husband of a woman amongst them. Working diligently, some on their embroidery frames, others on the black sewing machines set in front of them, they move their hands swiftly like magicians confident in their powers to create the unimaginable. The gaudy coloured beads and the gold tinsel thread shimmer as they catch the rays of the harsh sun to become an interwoven pattern, an embellished narrative of this unforgiving land.

It is of no surprise that when such a collaborative act occurs as part of a community engagement project, the participant’s own imagination and realisation of a collective spirit becomes a powerful and intrinsically empowering force. A deep engagement with other community members can significantly lead to transformation of the participant’s conscience where their expression is a means of emancipation. The process is more important, if not equal to the product, which in some cases may be tangible or take the form of creation of a worthy space in society.

The Humnawa (roughly translated as “companionship”) project has been such an inspiring and humbling story where two hundred women from four communities in Muzzafargarh, south of the mighty Punjab, bravely sought to make a difference in their lives and of those in their communities. In response to the Skills for Employability program initiated by the Punjab Skill Development Fund (PSDF), this unique intervention brought together four partners with a common objective. The School of Visual Arts & Design (SVAD) along with Sungi Development Foundation, Bunyad Foundation and SABAH, each contributing in their area of expertise, worked over a period of eight months to develop and showcase the products and talents of a group of women artisans skilled in embroidery, crochet, mukeish (flattened metallic embroidery), gota (gold/silver ribbon embroidery), quilting and basketry.

The challenge was multifaceted, much like the goals of the project. Not only was the objective to form a bridge between the artisan and the designer in order to develop an integrated approach towards skill development for income generation, but also to apply the core values of design thinking for holistic solutions in product development. Design is one of the most popular fields in institutes of higher education in Pakistan, offering career paths in popular subjects like visual communication design, fashion, textile, product, jewellery and accessory design. Young graduates are absorbed into the rapidly growing textile, fashion and advertising industries by corporations eager to feed the ever-increasing appetite of a consumerist society. With numbers increasing every year, many universities and colleges are faced with concerns of how to inculcate socially and ethically conscious designers within the parameters of a largely traditional academic structure and curriculum. An urgent need is to convince young designers that social responsibility is as important as the glamour in the design world. The prevalent socio-economic condition of Pakistan breeds a cruel disparity between the haves and the have-nots exacerbated by deep-rooted issues like feudalism, gender imbalance and illiteracy. Young learners are challenged when the bubbles of urban “privilege” are burst to reveal a “real” world. This brush with reality, in most cases, is overwhelming, especially for those breaking out of the “doctor-engineer” stereotype professions to pursue a career in the arts.

Perhaps the most valuable opportunity posed by the Humnawa project was to scratch the surface of this bloating bubble for a peek into how aspiring designers can make an equally worthy contribution towards society similar to any doctor, engineer or IT professional. A rewarding experience in the shape of a similar pilot project with the women of nearby Tarogil village had been recently initiated, which resulted in the forming of meaningful bonds whereby “village women turned from strangers into project partners”. Other workshops and interventions involving highly skilled textile and jewellery craftspeople had been also successfully conducted leading to ongoing collaboration for product development. However, at the core of such modules was the need for a deeper fulfilment, seemingly lost in a practical ruthless world, by interaction with “real” design problem solving.

Faced with realistic goals encompassing a broad portfolio of tasks in skill building, marketing, design management and product development, a comprehensive plan was drawn up for assessing the existing skills in the selected communities, addressing the gap and strengthening and improving the identified skills. Bunyad Foundation, an NGO already experienced in providing infrastructure for vocational training and outreach programs, facilitated the selection of communities in Muzzafargarh, thereby narrowing their focus on eight craft centers in the district of Alipur. Sungi Development Foundation, excelling in engaging and providing skill based training to women home based workers through the development of sellable products, would develop and implement specific training units. A partner organization of Sungi, SABAH (SAARC Business Association for Home Based Workers), whose main function was to act as a cooperative for home based workers, was instrumental in identifying appropriate clusters and skills, and supervise the quality control and production. Faculty and students from the departments of Textile, Fashion and Jewelry at the School of Visual Art & Design would develop and design a range of contemporary products drawing upon the skills of the artisans with the objective of establishing a sustainable form of livelihood.

The first visit was a memorable one, in many ways. A busload of enthusiastic students and eager faculty made the twelve-hour road trip for the preliminary assessment for the project. Meeting and getting familiar with the women and children at the designated craft centres was an eye opener for many students, especially with the language barrier as most women spoke only Saraiki, a local dialect. It was heart-warming to see how these women, often with their young children and domestic animals in tow, walked miles to the nearest centre for a day’s work and a glimpse of the dream of a better life. The sheer pride at being chosen for the project and a keen spirit to learn was so evident that even the roadblocks that day due to a murder in the nearby village (home to the legendary Mukhtara Mai) couldn’t deter them. Hence, amidst the intermittent exchange of gunfire and friendly conversations, we began to get involved in the many stories interwoven into the fabric of life outside the “bubble”. Three days later, back in the safety of our urban zones of existence, we tried to gauge the gaps in skills and training that needed to be addressed. For many students, it was an unfamiliar and unlikely design brief.

After an intensive period of research into the multilayered aspects of the existing craft samples from our first visit, the process of setting tasks revolving around colour forecasting, trend forecasting and material studies was initiated. On our second trip, after surveying the markets in close proximity to the centres, we selected samples of locally sourced fabric and thread to complement our prepared colour swatches as a follow up on the initial Gender Activated Learning (GALS) training which had begun soon after the first visit by Bunyad Foundation. By breaking down the products into motifs, colours, stitches and styles, we began to tread into familiar territory, discovering to our delight the very personalised names ascribed by the women artisans to traditional embroidery stitches. The Patakha stitch, literally meaning “explosion”, attributed to the humble sunburst stitch, was voted as the cheeky favourite of the lot, followed closely by the zig zag Motorway tanka (stitch) and the political heavyweight of them all, the Nawaz Sharif stitch, (christened after the current Prime Minister of Pakistan)! More animated exchanges revealed the often harsh realities of living a less than utopian life, but still being grateful for the simple pleasures on offer. It left us with a generous plateful of food for thought as we departed after the workshop, employing them to develop some new samples.

The next step was to build up on the prepared samples and start to develop a product range, which would help to connect the skills at hand with the demands of an urban consumer market. The purpose was to introduce unique hand crafted products with a “conscience” to an aesthetically savvy consumer looking for an alternate to the faceless, soulless goods hijacking the city markets. The most crucial aspect would be to ensure that the designs offered something unique yet remained culturally sensitive in order to compete with their more hybrid counterparts. Another equally important consideration was the ability to meet quality standards in terms of finishing, a feature lacking in most of the samples crafted. A collection of products was designed to encompass the diverse skills which were being practised in the target communities and included bags, wallets, table mats, cushion covers, tunics, scarves, lampshades and jewellery. A comprehensive booklet for each selected design was then produced, complete with templates for motifs, fabric and colour swatches, accurate measurements, patterns for cutting and sewing and finishing details. Another visit was coordinated with the centre managers to deliver and elaborate on each design, for sampling under supervision.

There was frustration amid the struggles of “doing and undoing” till the specific requirements were achieved on both ends. Once the first couple of finished products were materialised, this transformed to excitement. The promise of a trip to the city after this initial exercise was also a motivating factor, as all the women artisans, except for one, had never set foot outside of their community for most part of their lives. A visit to the vibrant and throbbing city of Lahore saw mixed emotions, from awe and wonder to the uneasy feeling of leaving the safety of home for the first time. The objective of this visit was to not only to introduce them to the complexity of the urban market and an understanding of current trends contributing to demand and supply chains in a sustainable small business model, but also to inculcate a sense of pride and ownership in their abilities. It had been observed that the craft centres located on the outskirts of the bigger towns had demonstrated a higher level of skill and insight into the complexity of the design process. Thus the purpose of this visit was also to stimulate and expose the artisans to the potential of development of their skills, thus contextualising the act of making as a powerful and meaningful means to an end.

With the deadline for the show approaching in two months, efforts multiplied to improve the consistency and finishing of each product, with many interventions to ensure that the designs would meet the expectations of the target audience. A marketing campaign was designed to run simultaneously by the students of the Visual Communication department as well as the Pakistan Fashion Design Council who had generously sponsored the exhibition space. The finished products were labelled and packaged and arrangements were made for the artisans to attend the opening night. It was only once that the designed products were displayed that the tireless efforts and commitment of all the stakeholders involved emerged in true form.

The enthusiastic feedback and the encouraging sales represented the incredible strength of a collaboration of minds and hearts. It also posed many questions for the future of such interventions that in the process challenge many aspects of the both the design and the crafts industry. One predominant issue may be the concerns around the assumed notions of “traditional” and “contemporary”, which remain unresolved in an attempt to redefine the identity of the craft within the relevant social and cultural context. This also prompts a question into the very the nature of the role of the designer as an interface between the artisans and the global market, and may serve to emphasise that such exercises should focus on training to develop the ability for independent problem solving. Moreover, and most significantly, it should be restated that the artisans involved in such interventions should not be considered as passive receivers in the process but as equal stakeholders, thus reaffirming the value, dignity and spirituality of indigenous art and craft.

Author

Sahr Bashir graduated in 2001 with a Postgraduate Degree in Design from UNSW Art and Design, Sydney, Australia. Currently Associate Professor and Head of the Jewelry & Accessory Department at the School of Visual Art & Design, Beaconhouse National University, Sahr took the lead in establishing the department, the first of its kind in Pakistan. With over fifteen years of experience in the Education sector, she has played a pivotal role in developing curricula and educational materials in addition to training faculty, professionals, craftspeople and students. Sahr has taken special initiatives to introduce product development and training modules for community engagement in liaison with established government and private organizations in Pakistan. This has led to the implementation of several design interventions for craftspeople and women especially from the underdeveloped communities of Punjab.

Sahr Bashir graduated in 2001 with a Postgraduate Degree in Design from UNSW Art and Design, Sydney, Australia. Currently Associate Professor and Head of the Jewelry & Accessory Department at the School of Visual Art & Design, Beaconhouse National University, Sahr took the lead in establishing the department, the first of its kind in Pakistan. With over fifteen years of experience in the Education sector, she has played a pivotal role in developing curricula and educational materials in addition to training faculty, professionals, craftspeople and students. Sahr has taken special initiatives to introduce product development and training modules for community engagement in liaison with established government and private organizations in Pakistan. This has led to the implementation of several design interventions for craftspeople and women especially from the underdeveloped communities of Punjab.