Mio Kuhnen Moth compositions. Brooches, mori-age, champlevéand cloisonnéenamel, 925 silver. Largest : 42 (diameter) x 8 mm(depth)

Nola Anderson writes about mother and daughter Helen Aitken-Kuhnen and Mio Kuhnen who share a deep knowledge of the language of materials to express the world around us.

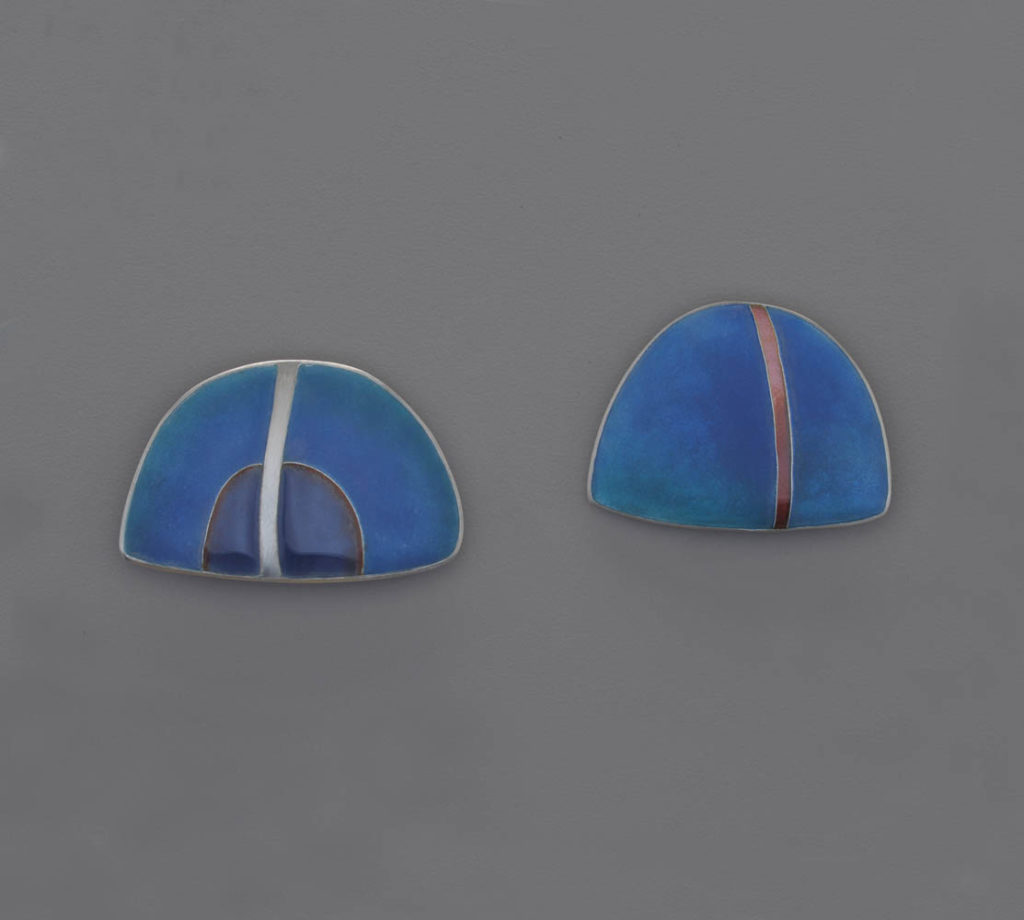

- Helen Aitken-Kuhnen Angry ocean brooches, moriage enamel, champlevé, cloisonné, 925 silver. 35-38 x 45- 53 x 4 mm

- Helen Aitken-Kuhnen Postcards, Brooch, moriage enamel, champlevé, cloisonné, 925 silver. 18 x 32 x 3 mm

- Helen Aitken-Kuhnen Black cockatoo resting, brooch. Champlevé enamel, 925 silver. 34 – 40 x 34 – 28 x 3 mm

- Helen Aitken-Kuhnen Angry Sea Anemone brooches, mori-age enamel, champlevé, cloisonné, 925 silver. 35-38 x 45- 53 x 4 mm

Helen Aitken-Kuhnen

When describing the art of enamelling in a 1911 edition of Studio magazine, the Japanese scholar Jiro Harada took obvious pride in the seemingly super-human effort such work entailed: endless patience, minute detail, profuse complexity and unwearying labour. [1] He listed examples of lives dedicated to the art: Namikawa Yasuki’s work could only be truly appreciated using a magnifying glass, and eighty-year-old Hayashi Kodenji had exhausted his life’s earnings in the quest for technical perfection. Harada wondered how this exacting art form might eventually find a place within a very different Western aesthetic. Some 70 years later Aitken-Kuhnen is exploring the same question.

As it happened, Aitken-Kuhnen’s pathway to the art of enamel began not through Japan but through the highly energised world of 1970s contemporary European jewellery. Her professional education was similar to that of many Australian jewellers at the time, with a Diploma of Art, Gold and Silversmithing at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, under the German jeweller Wolf Wenrich. Wenrich was particularly influential in exposing students to the world of intense experimentation in form and materials that characterised the new European work. Not surprisingly many Australian students, including Aitken-Kuhnen, continued their studies in Europe after graduation.

Aitken-Kuhnen was not however attracted by the new jewellery’s fascination with political or conceptual statements, abstract forms or what Damien Skinner termed the “critique of preciousness” which drove artists to explore alternative materials and found objects. [2] “I did all this”, she said, “so I could find a way to apply colour to my work.” Thus she chose to work with specialists in the art of enamelling: Sigrid Delius at the Fachhochschule, or School of Applied Arts, in Düsseldorf, and Alan Mudd at the Middlesex Polytechnic in London. She followed this with further work in Europe in the workshop of German gold and silversmith Johannes Kuhnen, whom she later married. They moved to Australia in 1981 and established a joint studio workshop.

Aitken-Kuhnen also pursued further studies in enamelling techniques through workshops with Tsuruya Sakurai, a long-time employee of the Japanese firm Andō Cloisonné. The company was founded in 1880 and boasts a long genealogy of master enamelists, a reputation for technical excellence and a seemingly endless list of enamelling techniques: musen, yūsen, tōtai, shōtai, saiyū, moriage and more. By working with Tsuruya Sakurai over a number of years both in Japan and Australia Aitken-Kuhnen developed her skills in enamelling techniques, including cloisonné, doro, moriage and the ancient art of three-dimensional plique-à-jour (which is as complicated as it sounds). Given the art of plique-à-jour goes back to Byzantium, this was a case of west-meets-east-meets west again.

Since her earliest work then, colour has been one driving force for Aitken-Kuhnen. The other has been narrative. “I work from what is around me”, she said. That has ranged from landscape scenes inspired by her workshop in Melbourne—the Kalorama series of the 1980s—to the natural landscape series which have come to the fore since they moved to the Canberra region in 1985. Sub-sets of the general landscape theme have also included motifs such as the Angry Sea Anemones and the Cockatoo series. The various enamel techniques which Aitken-Kuhnen uses have been a perfect choice for the work.

Aitken-Kuhnen’s enamel work is her own version of Harada’s east meets west, in both process and concept. Harada noted two opposite forces at work in Japanese art: the one suggesting endless patience in the execution of minute detail, which he felt was exemplified in the art of enamel, and the other a momentary concept of “some fleeting idea carried out with boldness and freedom”. Rarely, he admitted would both find equal footing in one piece. Aitken-Kuhnen’s gift has been to embody both concepts by using the exacting art of enamel to express fleeting moments from the natural world. It’s a fascinating set of opposites.

It’s seen most clearly in the 2018 Flight series in this exhibition. Here Aitken-Kuhnen uses the enamel process of cloisonné, in which fine wires are used to separate the coloured enamels prior to firing. This is the time consuming, arduous work which requires patience and skill in laying and firing the powdered enamels. Aitken-Kuhnen’s final design, however, embodies what Harada would have recognised as a fleeting idea of “boldness and freedom”, translated here into the quick, darting traces of birds in flight. The colours are muted—soft hues against light sky —with the small figures leaving momentary traces across the sky. Hardly there, and quickly gone from sight.

The quick gesture is present in a quite different way in the Black Cockatoo series, the latest iteration of Aitken-Kuhnen’s ongoing theme of Australian birds which has included sulphur-crested cockatoos, ground parrots and grass parrots. These pieces are made using the champlevé technique in which the enamel is contained by slightly engraving into the surface of the supporting metal body.

In the Black Cockatoo pieces, Aitken-Kuhnen injects a note of wit with the cheeky over simplified squarish bird-body topped with the idiosyncratic flash of yellow feathers. It’s a familiar and instantly recognisable sight to any Australian. It’s also a good example of Aitken-Kuhnen’s use of colour, which is as important to the overall success of the pieces as is the ‘graphic’ shape of the body.

Aitken-Kuhnen’s landscape series using the champlevé process has also been a continuing theme, going back to the beach brooches of mid-1980s and the Land and Sea brooches of 2011 onwards. It continues her interest in the ‘narrative’ of the Australian landscape, again expressed in these pieces through washes of colour with a simple abstract composition. These pieces offer an interesting contrast of scale. The enamel process, and the fact that these pieces are intended to be worn, impose certain functional restrictions of size and weight. To Aitken-Kuhnen the essence of the pieces lies in their intimate scale. But the compositions themselves are inspired by the vastness of ground and sky, foreground and horizon. It’s an expansive vision compressed into miniature. The same process is at work in the pieces made from the doro technique with their slight vertical notes of fine wire.

Most recently Aitken-Kuhnen studied the moriage technique with Tsuruya Sakurai, a process in which the enamel is built into three-dimensional layers between cloisonné wires. This technique forms the basis of Aitken-Kuhnen’s Angry Sea Anemone series. As in the Black Cockatoos, Aitken-Kuhnen introduces a slightly whimsical note in these works, this time through a high- keyed palette and simplified geometric patterning.

Aitken-Kuhnen views every new series as a play of ideas and techniques, building on experience, testing new waters. She is giving a modern twist to Jiro Harada’s vision of enamel artists who worked with “infinitely laborious experiment, always with hope … who wooed chance with loyal constancy”. [3]

Nola Anderson, 2018.

[1] Jiro Harada, “Japanese Art and Artists of Today – VI Cloisonne Enamels,” Studio International 53.1911 (n.d.), https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/studio1911b/0292 Page: 271 DOI issue:

[2] Damian Skinner, All The World Over: The Global Ambitions of Contemporary Jewelry | Art Jewelry Forum, accessed September 24, 2018

[3] Jiro Harada, op. cit.

- Mio Kuhnen The Amazon River series. Brooch, champlevé enamel, 925 silver. Smallest: 33 x 3 mm Largest: 53 x 3 mm

- Mio Kuhnen Moth compositions. Brooches, mori-age, champlevéand cloisonnéenamel, 925 silver. Largest : 42 (diameter) x 8 mm(depth)

- Mio Kuhnen The Amazon River and Moths from the Jungle. Pendants, champlevé enamel, 925 silver. 42 x 8 mm

- Mio Kuhnen Explorers wife, moths from the Ama-zon jungle series. Brooch, champlevé and cloisonné enamel, 925 silver. Largest : 42 (diameter) x 3 mm

Mio Kuhnen

Mio Kuhnen’s jewellery is full of what Kitty Hauser calls “hidden stories”. Hauser was talking about the imagined histories that archaeology reveals within a landscape. his archaeological imagination builds stories about our world which have no presence in real time. [1] They exist as traces revealed by the creative eye. Kuhnen builds her stories in a similar way, but this time through a more direct intersection between art and science.

Kuhnen came to jewellery through a slightly less well-travelled path than most, having first completed a degree in Environmental Science and Geology at the Australian National University in 2005, specialising in marine and sedimentary geology. She now lives in Queanbeyan, near Canberra, and continues to work professionally in her scientific specialty. A year after her graduation she also began working in jewellery in the joint studio workshop of her parents, Helen Aitken-Kuhnen and Johannes Kuhnen, both of whom had trained in Europe and have established careers in contemporary jewellery and metalsmithing. Kuhnen has also undertaken a number of master classes, one with the German gold and silversmith Godwin Baum and two with the Japanese enamelist Tsuruya Sakurai. The latter workshops, in which she was joined by her mother Aitken-Kuhnen, were inspirational. suruya Sakurai, she observed, was “fearless” in his approach and confidence which was born of his then 80 years of experience.

The conceptual complexity of Kuhnen’s jewellery has grown over recent years. The work in this exhibition, for example, builds on earlier pieces from 2016 such as the Murray Canyon and Chaos before the abyss series, the first major series in which Kuhnen fully exploited that space between science and art. hose designs drew on satellite generated images of the sea floor of the Flinders Commonwealth Marine Reserve off the coastline of Tasmania and the Murray Canyon just off South Australia. his type of imaging, called bathymetry, uses satellite data which maps the sea floor in diagrammatic representations, revealing deep crevices, sharp angles and maze-like fissures. It’s a fantastic world which, given the extreme depth, otherwise remains hidden from view. The images are schematic and imperfect, just as any archaeological recreation might be. ut unlike Hauser’s topographical archaeology, these hidden stories” have the wonderful irony of being both real – based on exact scientific data – and at the same time inaccessible and impossible to imagine in any complete form.

In Kuhnen’s works, there are two final transformations. An image built on collected data is then re-imagined in embossed metal. And then there is a transformation of scale: the vast miles of inaccessible sea floor is condensed into small circular metal forms that can be worn and held.

As part of her geological work, Kuhnen has also studied the patterns of ocean floor sedimentation laid down over centuries, including those of the Fitzroy River Basin on the Queensland coast, the largest river system to flow into the Great Barrier Reef. These layers of sediment reveal much about the effects of climate change and land use on our natural environment. uch investigations formed the basis for her earlier fluvial delta series. They have been developed in this exhibition as the Amazon series.

The Amazon series is based on aerial photographs of the vast Amazon delta that spreads across the top of the South American continent. gain, it is a topography that is not immediately visible from the ground, it needs to be either captured from the air or experienced by walking. Kuhnen’s jewellery again transforms this into the intimate scale of round pendants which carry the patterns of the delta embossed in silver with small flashes of enamel. he delta patterns follow what Kuhnen calls the ‘blood lines’ of settlements as each community has expanded its pursuit of food and a livelihood. It’s another version of hidden stories, as the delta flow maps the interaction of community and landscape. uhnen is building a virtual map of several layers of time and space. he delta pattern can be read as a snapshot of one moment in time, a map of sedimentation over centuries, and the relatively brief but often destructive impact of recent land use. Kuhnen adds one interactive element to this series by providing an embossed paper print of the delta flow pattern, against which the individual brooches can be located when the jewellery is not being worn. inally the delta image is repeated in small shallow bowl forms, again with touches of enamel colour to accent the concept of movement across the surface.

Kuhnen also draws on natural history for her inspiration. In this show, there are two quite different interpretations of this theme. ne, using her favoured circular brooch format, captures the tiny, flitting movements of moths native to the Amazon region. The second is based on a more geometric interpretation of the moths. n these Kuhnen pares back the image to simple wing forms and small dots of colour. When the brooches are seen together the triangular geometry of the wings creates an uncanny sense of movement. In the third moth series, Kuhnen uses a cloisonné technique to create a more graphic interpretation with bright patches of vivid colour.

In the Lava series, Kuhnen returns to topography, this time using embossed, engraved and enamelled designs on slightly concave circular silver forms. The series is based on the dramatic lava flows of Big Island in Hawaii, which gives her another chance to examine the forces of nature seen against the perspective of the whole sweep of geological time. A the magma erupts, new lava flows over old, creating a labyrinth of nooks, ripples and crannies which Kuhnen captures in miniature. The scale changes from mammoth forces of nature to something controlled and intimate.

Kuhnen’s work plays with both time and space, looking backwards to ancient history, and hoping to influence our current perspectives. I reminds me of computer scientist Daniel Hillis’s lament that in our current rush towards the future our sense of time has been dramatically foreshortened. Instead, he exhorts us to take a much longer view based on time slowed, a clock that “ticks once a year, bongs once a century, and the cuckoo comes out every millennium” [2]. Hillis is actually building his clock. It will be buried out of site in a mountain in Texas. Kuhnen is beginning to build the thought into her own work with her vision of a natural world built on ancient time and hidden stories.

Nola Anderson, 2018.

[1] Kitty Hauser, Shadow Sites: Photography, Archaeology, and the British Landscape 1927 – 1955. (Oxford University Press on Demand, 2007).

[2] “WIRED SCENARIOS: – The Millennium Clock Danny Hillis,” WIRED, accessed September 27, 2018

Transfer – Helen Aitken Kuhnen and Mio Kuhnen is at Bilk Gallery, Wednesday 24 October – 23 Friday November 2018