- Workshop in Ahmedabad – weavers looking at colour

- Workshop in Ahmedabad – weavers looking at colour

- The Bolgatanga weavers on NID campus Ahmedabad

- Workshop in Ahmedabad

- Workshop in Ahmedabad

- Workshop in Ahmedabad

- workshop in Ahmedabad

- new hats taking form

- Hats in the Bolgatanga market, October 2014

- Working on ikat-type dyeing

- Workshop in Ahmedabad

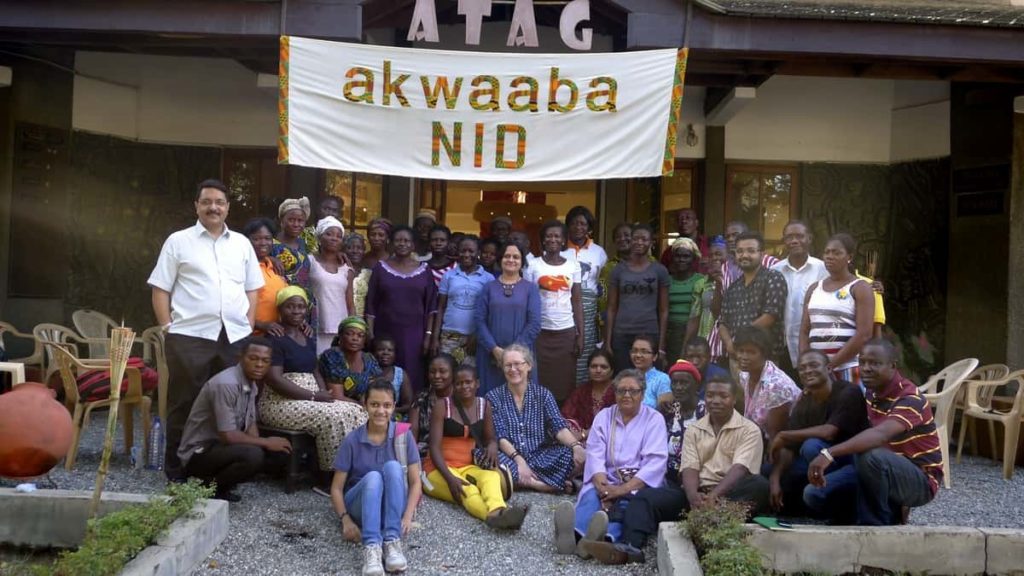

- Planning the workshop at Aid to Artisans, Ghana

“How are you going to work with the already perfect Bolga basket to increase incomes for weavers?” I asked Krishna Patel, head of the design team from India’s prestigious National Institute of Design (NID) at the beginning of the Indian Government-funded design programme for women basket weavers in Ghana’s Bolgatanga region. How would it be possible to adapt what looked like a wonderful basket so that, reinvented and properly priced, it could be offered to global markets? The grass weavers from Bolgatanga in Ghana’s Upper East Region rely on basket sales as their sole source of cash income to supplement livelihoods based on subsistence farming. And at the time, their traditional international markets had almost collapsed.

It was the last day of our exploratory assessment workshop in October 2013 in Bolgatanga and the team comprising Patel, as well as senior faculty member and head of NID’s Outreach Programmes, Shimul Mehta Vyas, post-graduate student, Palash Singh, and me, from The New Basket Workshop, were headed back to the nation’s capital city, Accra. We had heard from Ghana’s Bolgatanga weavers that they needed direction for innovative high quality products. This especially so since cut-price copies woven in sea grass and commissioned in Vietnam had flooded their established markets. The deluge of Bolga-basket-look-alikes from the East caused the almost total collapse of Ghana’s basket industry. And when Bolga baskets were reintroduced to global buyers through international trade fairs in early 2013, exporters in an effort to attract buyers back to the Bolga product, accepted prices pushed to rock bottom levels. The effect of low prices for huge orders to international discount stores by many of the leading Ghana basket exporter businesses meant that quality was really compromised and what was supplied was nothing like the quality of earlier years. Buyers complained of colours running, colours fading, poor weaving quality and baskets that split easily. On the producers’ side, many of them wondered whether continuing to supply handcrafted items was worth their time at all – except they needed the cash…

The NID’s work in Ghana formed part of a larger programme supported by the Government of India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry under the aegis of its Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, and administered by the Ministry of External Affairs. Its aim was to increase livelihood opportunities for women basket weavers in five countries in Africa drawing on the design skills and experience of the NID. As part of The New Basket Workshop, my role was to coordinate and facilitate the programme on the ground.

The purpose of the first visit by the team was to see the weavers in their environment and get some understanding of basket production in the area. Grass processing, dyeing, weaving and finishing were studied in detail. The scoping exercise also highlighted some of the problems confronting the weavers: issues such as the unavailability of good quality fibre-reactive dyes, an ineffectual dyeing process – this was partly due to restricted access to water and the expense of fuel, unavailability of good leather for embellishments, and inadequate quality control. Basket weavers commented on how difficult it had been for the industry to recover from the sea grass copies and complained about the terrible low prices they were offered for traditional baskets. Members of the Ghana basket exporters association criticised the poor quality of products, both in terms of weaving and dyeing, as well as slow delivery. Lack of innovation also restricted what could be offered to the international markets. Buyers we contacted in Europe complained about how the colours in the baskets faded and how poor quality had become.

My background research of the basket weaving industry in Ghana revealed that many regarded it as highly exploitative. Keen to avoid this taint on the programme, I contacted the Gayle Pescud at the G-iish Foundation, a Ghana-based organisation specialising in recycled materials, but which was also at the time researching wages in the Bolgatanga basket industry. Gayle guided me to a few businesses, one of which expressed interest in working with the designers from India. And that was how we got to meet and work with the weavers of the Baba Tree and its owner, Gregory MacCarthy. Together with these weavers we worked closely with long-time veterans of the Ghana craft scene, Aid to Artisans Ghana (ATAG) and its director, Bridget Kyerematen-Darko. To a lesser extent we collaborated with Mawuli Akpenyo from Delata, a Ghana craft exporter.

Armed with information from Bolgatanga and Accra, as well as loads of basket samples and raw materials like market dyes and grasses, the team returned to process it all in the NID’s workshops, laboratories and studios in preparation for the next phase of the programme – a series of collaborative workshops at the NID’s campus in Ahmedabad scheduled for December 2013.

Meanwhile, in Bolgatanga, the weavers prepared themselves to travel to India. And local basket politics raised its head making getting ready for international travel a more gargantuan undertaking than was absolutely necessary – especially given the very limited time available. It involved applying for passports – not an easy procedure for rural folk, many of whom did not have birth certificates and some of whom are functionally illiterate. Many had never left the sparsely populated region they call home, nor ever travelled to Accra, Ghana’s bustling capital of four million people.

There were scary moments when it seemed as if none of them would leave Ghana at all. I spent hours on the phone as Gregory MacCarthy working together with Elizabeth Adongo from Ghana’s Centre for National Culture in Bolgatanga and Accra-based Bridget Kyerematen-Darko managed the elaborate and often fraught operation. Matters were not simplified with the emergence of a local rumour that the weavers were flying to India to teach their skills to Indians while allegations swirled that MacCarthy was trafficking in basket weavers! Extensive assistance from the office of India’s High Commission in Accra ensured that twenty Bolgatanga weavers eventually boarded a plane on 30 November 2013. They arrived in Ahmedabad a day later, dazed but delighted. Accompanying them to participate in workshops tailored for management and export were MacCarthy, Kyerematen-Darko, Adongo, Diana Korto from ATAG and an academic from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology’s Department of Integrated Rural Art and Industry, Dr Abraham Asmah.

In Ahmedabad, the Ghana workshop crew, steered by the NID’s Outreach Department, consisted of senior faculty, experienced designers, postgraduate students and a small army of senior support technical staff. Fields of expertise included leather, bamboo, apparel, textiles and dyeing. This many-pronged approach illustrates what makes the NID’s contribution to craft and the development of grassroots livelihood opportunities unique. It’s a huge multi-disciplinary team that comes together to design the difference.

To paraphrase the thoughts of a former Institute director, Ashoke Chatterjee: Over many years the NID has forged an extraordinary ethic in its partnerships with artisan communities, resulting in its becoming trusted as a development organisation. One of the reasons he cites for this notable success is because neither the Institute nor its designers use the artisans as a means of self-promotion. Focussing instead on the critical objective of assisting craft artisans to achieve sustainable livelihoods, the NID works to bring out the very best in terms of quality and innovation. Seeking not to create a source of dependence for rural artisans, but rather developing a resource for learning that translates into an ability to increase livelihood opportunities, it enables them to have greater control over their lives and futures.

These were the principles applied by the team in Ahmedabad so that the weavers were drawn into the strong collaborative undertones. I was amazed at how this helped the weavers from remote Bolgatanga to adapt to life in Ahmedabad and the studios and how they pushed themselves to discover the new possibilities of the materials and how wonderful the quality of the work was. The Ahmedabad workshops also gave the weavers and the designers the opportunity to find out what didn’t work – a great luxury of product workshops.

The following year in April the team from India travelled to Accra for the third phase of the programme – an in-country workshop at the spacious premises of Aid to Artisans, Ghana. Included were activities combining the use of wood, metal, bamboo and quality leather into new items. One of the most important components of this workshop was a carefully researched dyeing procedure for the grass based on extensive tests carried out in Ahmedabad based on locally available materials.

Passionate about grassroots development, the present director of the Institute, Pradyumna Vyas, iterated one of the NID’s principles: “The NID’s product development philosophy includes incorporating only locally available materials which are capable of being sustainably used in the weavers’ village environment.” It certainly would have been easy for the programme to use high-quality fibre-reactive Indian-manufactured dyes for quick and stunning results. But such dyes are not obtainable in Ghana. Instead the team evolved a method to work with dyes bought in Bolgatanga’s markets and other materials like locally made soap and vinegar for domestic use. The results yielded the best outcomes possible under restricted local conditions.

The design team working with the same team of highly qualified weavers who travelled to India plus a cohort of additional master weavers from Bolgatanga developed extensive new product ranges. Integrating traditional Indian textile techniques into the grass dyeing process, ikat-type effects were created. Leather skills were shared to give the new bags, baskets and shoppers extra strength and beautiful handles. Astonishing ranges of lighting, with great market potential, emerged. Fine grass jewellery – an innovation for these artisans – was woven. Traditional Bolgatanga hats were reshaped and the use of forms introduced to ensure consistent sizing. Baskets with stunning unformed organic shapes were presented along with lidded containers and trays.

The results of the programme went beyond a range of new techniques, forms, colours and designs and included a fundamental cultural exchange. Participants said what they have learned from the NID and India goes far beyond the manifested outcomes.

At the beginning of the programme Bridget Kyerematen-Darko said “Ghana is a craft producing nation and I have long felt that we have most to learn from India, where craft is also so important. It is the most important country that we can look to. The idea that Ghana artisans would travel to India and look at it through the eyes of artisans – well they would learn more than they could anywhere else.”

Nearing the end of the third and final workshop the weavers said that with their extended understanding of their own techniques and of the materials’ capacities they would continue to develop their own product ranges. Importantly they would teach others to do the same. Commenting on the more than 100 new pieces that were shown in Accra, master weaver Akabare Abentare said; “See how many products there are here! We want the others in Bolgatanga to see these and we will teach them how to make them. This is much more than the cheap copies of our baskets.”

designing the difference – Ghana gave confidence to the weavers’ creativity. Their personal growth through travel and contact with Team NID enabled them to take on more assertive community roles. During the workshops the weavers showed they are capable of producing items of exquisite fine quality capable of garnering proper prices for well-crafted work.

But only time would tell if the collaboration had any lasting effect….So we were really delighted to receive a long and detailed email from Baba Tree’s MacCarthy in September 2015.

The highlights of that mail are: “Business is going well. We are up around 30% on last year. We are also starting to realise a small profit.

There are so many design ideas swimming around in my head that don’t come to fruition because of our workload. The reason there are so many design ideas swimming laps inside my noggin is a direct result of our experience at NID. It really knocked me around – certainly out of my complacency – and clearly illustrated what could be done.

Of course, the weavers have benefitted from India’s intervention. Their horizons were expanded and they definitely make more money. (* FP – I have kept actual figures back – the daily rate for weavers has more than doubled since 2013) …That is quite an intervention wouldn’t you say? And we hit higher than that when we were informally selling baskets retail last Christmas. I derived great satisfaction from that.

The quality of weaving, finishing and colour design is light years ahead of where we were.

The intervention was huge. “Very much worthwhile!!!!” would be the understatement of the year. “

If you look at the Baba Tree’s website you will see Pakurigo Wave baskets developed during the workshops together with images of their weavers.

To conclude as Pradyumna Vyas says, “Through design the NID assists artisans at grassroots level to improve their access to the world’s consumers. Design gives them the chance to be a part of the global economy – and international consumers are looking for good quality well designed items with a feel-good factor.”

Background to the Ghana workshop

The work in Ghana is part of a larger programme funded by the Government of India. At the India Africa Forum Summit-II held in May 2011, India’s Government offered a major design intervention to women basket weavers in five countries in Africa. The project is implemented by the NID, under India’s Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, and is supported by the Ministry of External Affairs. It aims at empowering rural weavers in Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi and Zambia.

The purpose of the initiative is to adapt sensitively basket-making traditions, practices and challenges facing Africa’s women basket weavers, through drawing on the experience and knowledge of India’s traditional craft and highly developed design sectors. With the aim of increasing income generation opportunities, the project scope includes training of trainers, collaboration on product development and product range diversification, and brand building. By the end of the programme, 125 weavers will have travelled to the NID’s campus, 25 from each of the five countries.

The NID, in association with South African-based NGO, The New Basket Workshop, as project consultant, and local consultants Aid to Artisans Ghana and The Baba Tree, began the Ghana project in October 2013 and completed it in May 2014.

designing the difference is indebted to Jet Airways for its generous support of this programme

Interested in the products from this unique collaboration? Please contact Aid to Artisans Ghana at bridgetatag@yahoo.com or the Baba Tree at

In November 2014 the G-lish Foundation published its report into the Bolgatanga weaving industry and this can be read here.

Author

Frances Potter worked first as a researcher and later during South Africa’s turbulent 1980s as a human rights lawyer. In 2002 she was fortunate to combine her interest in rural development with her love for craft and art when the US-based NGO Aid to Artisans employed her as a marketing consultant. With ATA she worked in South Africa, Tanzania and Mozambique. She established Aid to Artisans South Africa Trust and The New Basket Workshop. From 2008 she worked with basket makers in Zimbabwe, Ghana, Ethiopia and South Africa. In 2011 she was hired to consult to India’s National Institute of Design on the implementation of a five-country basket initiative in Africa. Work with India included consulting to the National Centre for Design and Product Development on projects in Zimbabwe, Ghana and Ethiopia.Over the years she has been a judge for UNESCO’s Prix d’Excellence and Label d’Excellence in Burkina Faso, Gabon and Mali as well as serving on the jury for UNESCO’s International Fund for the Promotion of Culture. Frances is an advisor to the Joburg Fringe, as well as to the Africa Craft Trust and RIDA.

Frances Potter worked first as a researcher and later during South Africa’s turbulent 1980s as a human rights lawyer. In 2002 she was fortunate to combine her interest in rural development with her love for craft and art when the US-based NGO Aid to Artisans employed her as a marketing consultant. With ATA she worked in South Africa, Tanzania and Mozambique. She established Aid to Artisans South Africa Trust and The New Basket Workshop. From 2008 she worked with basket makers in Zimbabwe, Ghana, Ethiopia and South Africa. In 2011 she was hired to consult to India’s National Institute of Design on the implementation of a five-country basket initiative in Africa. Work with India included consulting to the National Centre for Design and Product Development on projects in Zimbabwe, Ghana and Ethiopia.Over the years she has been a judge for UNESCO’s Prix d’Excellence and Label d’Excellence in Burkina Faso, Gabon and Mali as well as serving on the jury for UNESCO’s International Fund for the Promotion of Culture. Frances is an advisor to the Joburg Fringe, as well as to the Africa Craft Trust and RIDA.

Comments

I am very proud of this!

Felt happy while reading, to know that NID is spreading helping hands all over the world.

Felt happy while reading to know that NID is spreading helping hands all over the world.

I am so impressed and proud. What and incredible project.

This project show cases the ability of southern organizations and countries to contribute towards improvement of women’s livelihoods through crafts.. Congratulations to all and especially to ATA in Ghana and the New Basket Workshop in South Africa

Frances, this is an excellent article. Some of the visuals of baskets I saw with Babatree last festival season were fantastic. Good wishes to all the basket weavers and you.