Still frame from Mbira.org video of Dzapazi Mbira Group playing Bhuka Tiende 2016.

In the third instalment of #africamade_n_played, Gary Warner reveals the inner life of this captivating instrument from southern Africa.

The Mbira DzaVadzimu (voice of the ancestors) of the Shona people is one of the most widely known African instruments outside that vast polyglot continent. In Western musicological typology, the mbira is of the lamellophone family, instruments in which sound is generated by plucking or striking flexible tuned strips of metal, wood, bamboo or other materials fixed to a sounding board or box. The mbira’s distinctive form and sound are well known beyond its 1,300-year-old cultural origins in what is today Zimbabwe and Mozambique. But throughout the continent there are many other similar “thumb piano” instruments with diverse variations of materiality, form, playing style, tuning preference and local language names—likembe, sanza, kongoma, kisanji, okashandja, and karimba are only a few of them.

Mbira is a Shona word for both the instrument and the music generated with it, music that anchors the people of the present with their ancestors, the spirit forms of passed family members, past tribal leaders, and cosmologically ancient entities that influence weather, crops and human interactions. Mbira music is played in many different social contexts from age-old spiritual ceremonies to weddings and funerals, for divination and guidance, and personal meditation and well-being.

During the long era of European patriarchal exploitation of Africa for its wealth of raw materials and enslaved labour, colonial governments and Christian missionaries forced African peoples to abandon their traditional cosmologies, languages and cultural expression. These destructive policies included the suppression of mbira music and ceremony.

During the twentieth-century struggle for independence from colonial rule, popular activist musicians such as Thomas Mapfumo used electric guitar versions of traditional mbira to galvanise African people to overthrow the colonial oppressors. He was jailed for his sonic stance. After gaining independence in 1980, mbira music was again heard widely in Zimbabwe. Still, when Mapfumo’s music started rallying critics of Robert Mugabe’s brutally corrupt regime at the end of the 20th century, his music was again banned, and he was forced to flee to the USA. More recently, mbira playing has diffused beyond the shores of Africa to be taken up by musically curious people, professional and amateur, all over the world.

Mbira dzaVadzimu, by Rinos Mukuwurirwa Simboti, Harare/Mufakose, Zimbabwe, ca. 1980. University of Göttingen, Collection of Musical Instruments, Inventory No. 1303. Photo: Stephan Eckardt

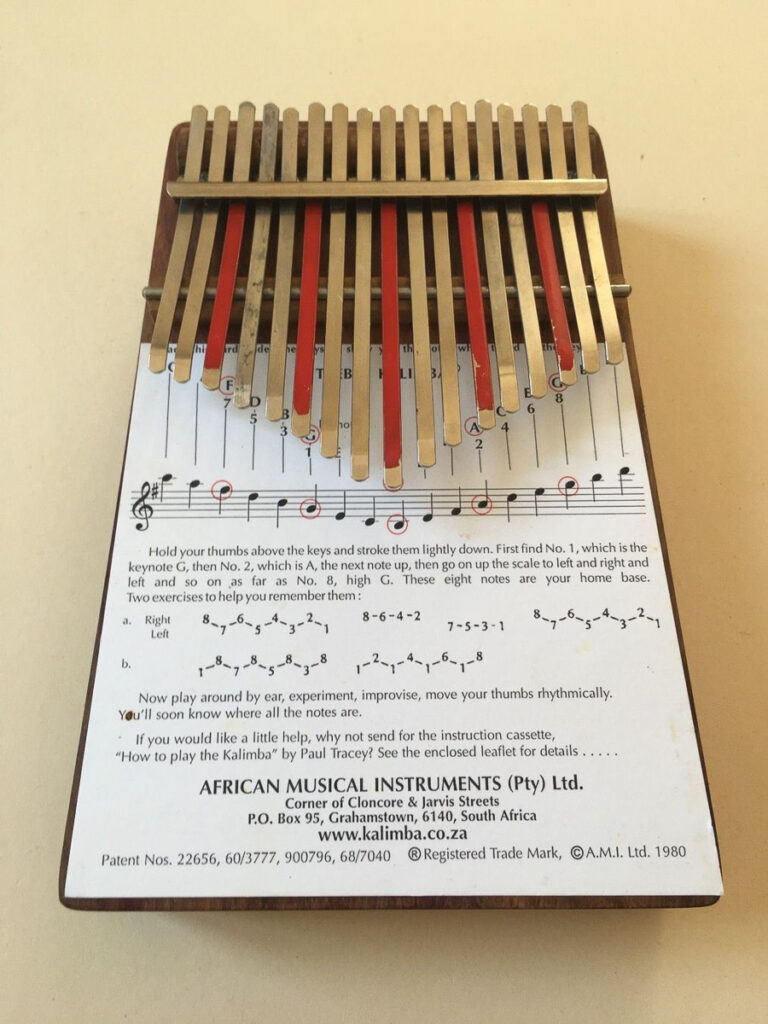

The mbira player holds the instrument in both hands. It usually has 22 to 28 carefully arrayed steel tines, flattened and widened at the playing end. A doubled row of 11 to 14 on the left side is played with the thumb of the left hand. A row of 10 or 11 more on the right is played with the thumb and index finger of the right hand. The steel tines are held in tension over a metal bridge, and the whole assembly is tightly fixed to a solid block of hardwood, the gwariva, that has a smoothed finger-sized hole in the right-hand bottom corner. The player pushes the pinky finger of their right hand through this hole and tucks the fingers of their left hand under the other side of the gwariva, to firmly grip their mbira. This arrangement leaves the thumbs and right-hand index finger free to pluck the tines.

The double-layer of left-hand tines are lower-pitched, fixed one row above the other, alternating up-down-up-down from edge to the centre of the gwariva. The bottom tines are longer than the row above, with adjacent up-down pairs being approximately an octave apart. The single-layer right-hand row is higher pitched.

Another interesting sonic element completes the mbira sound—an assembly of small objects, the machachara, that rhythmically rattle and quiver in vibrational sympathy with the plucked lower notes. Sometimes the machachara is made from beads or metal loops strung on wire, but most often used are metal bottle caps loosely fixed with wire ties onto a metal strip spanning the gwariva. The machachara produces a rhythmic buzzing that significantly complexifies the intensity and sonic qualities of the instrument by generating sounds redolent of wind, rain or whispering voices. It is believed this sound serves to attract the ancestral spirits and helps clear the mind of listeners.

Finally, the mbira is fitted inside its deze—an ample calabash, dried, halved and hollowed—with a stick pushed between the edge of the gourd and the top of the mbira. The deze will often have another circle of machachara fixed around its perimeter or base. In the past, cowrie shells were used; today, bottle caps are more readily available, durable and strong sounding.

In Zimbabwe, mbiras are still traditionally made by village-based craftsmen, using iron tools, small forges and locally sourced insect-resistant hardwood timber from the mubvamaropa tree (Pterocarpus angolensis). While the basic mbira form is fixed by tradition, each maker has personal design, materials, build and tuning preferences. Nuances of tine shape and material origin, machachara and bridge construction, quality of gwariva carving and fixing details—all contribute to the individual spirit and sound of each unique hand-made mbira.

From Mbira to Kalimba

Hugh Tracey recording a Chopi ensemble in Mbanguzi village, Chopiland, Mozambique, 1948. ©ILAM Archive and Jonathon Rees

On the death of his father, an English country doctor from Devonshire, teenaged Hugh Tracey was sent from England to (then) Southern Rhodesia to work on his brother’s tobacco farm—colonially stolen land allotted to Leonard Tracey for service in the Great War. Young Hugh was immediately entranced by the traditional singing and mbira music he heard there, played by Shona labourers on the farm. He learnt the Karanga dialect of the Shona language, and upon realising missionaries were actively suppressing mbira music and its associated cultural traditions, decided to work out how to make audio recordings of African music for posterity.

This epiphany began his lifelong passion for travelling the continent to audio record local live music. Nineteen field trips between 1929 and 1973 resulted in over 20,000 field recordings and a significant collection of 350 traditional instruments from diverse African language groups.

He developed his recording methods in response to the unpredictable exigencies and immediacy of fieldwork and four decades of technological evolution. Early on, he had a 100-metre cable made to link his recorder to the noisy generator supplying its power. He always recorded in mono and worked with a microphone on a short handheld ‘boom’ that allowed him to move around as emphasis shifted during a performance.

For decades Hugh Tracey diligently notated the diverse tunings of African instruments, with a particular focus in the various lamellaphone forms. He documented more than 100 distinct “thumb piano” type instruments, each with its own crafted materiality, tuning, note layout, and song repertoire. In the 1950s, living in apartheid South Africa (a political regime he opposed), he developed and began manufacturing a small steel-tined, sweetly tuned instrument he named the Hugh Tracey Kalimba. What started as a potential income stream to finance his ethnomusicological expeditions became the African Musical Instrument company that continues to manufacture his eponymous adaptation of an ancient pan-African musical instrument form, in Grahamstown, South Africa.

Hugh Tracey Kalimba – 17 key Treble c1980, with factory-provided instructional notation sheet placed on the instrument.

Hugh Tracey’s extensive library of field recordings, consolidated as the International Library of African Music (ILAM), is now a prestigious research institution within South Africa’s Rhodes University. ILAM promotes the research and study of African music and oral arts, contemporary field recording, and recording repatriation projects.

Links

Mbuya Beulah Dyoko (1944-2013), the first Zimbabwean woman to record mbira, playing and interviewed in 2013.

Dzapasi Mbira Group plays Bhuka Tiende, 2016

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVRckuNFSfE

Dzumba Dze Mabwe – Casa de Pedra is an hour-long auteur documentary made by Afro-Brazilian creator Lwiza Gannibal in 2016. Lwiza travels in Africa seeking out connections to her African heritage through traditional music. The film documents her interactions with mbira makers, players and teachers, as well as rural village life in Zimbabwe.

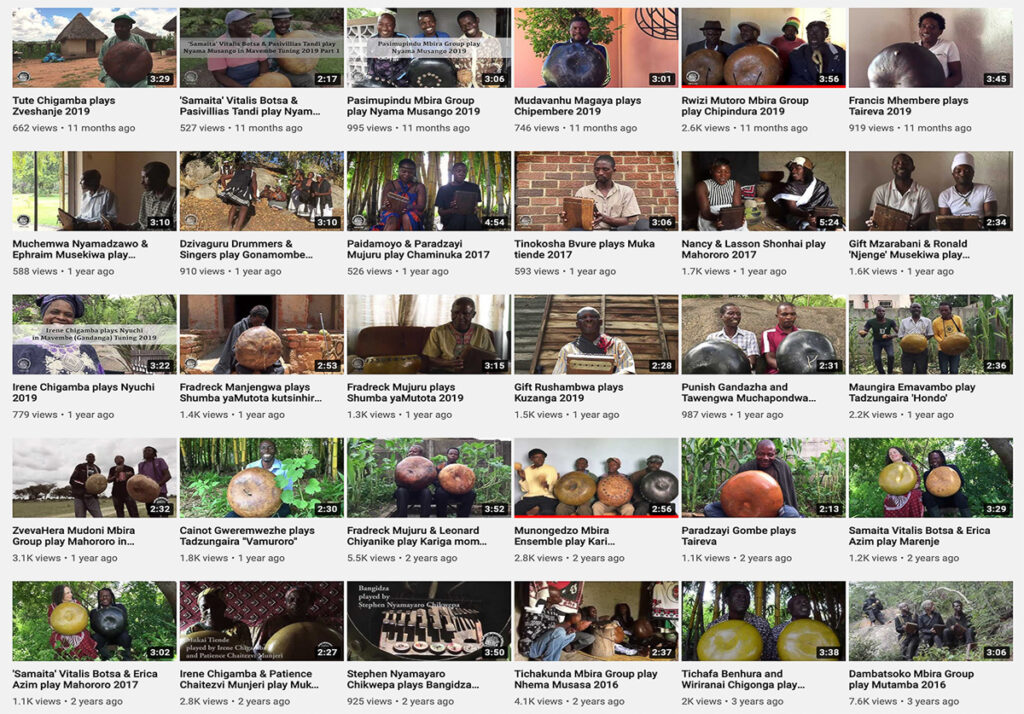

Sample of Mbira.org YouTube channel videos page. https://www.youtube.com/user/MbiraOrganization/videos

Mbira is a non-profit organisation started in 1998 that operates between California and Zimbabwe. It supports 300 traditional musicians and 20 instrument makers living in Zimbabwe, through sales of recordings and instruments. This link shows mbiras made by different makers, revealing the many nuances of formal variation.

This link is to the Mbira.org YouTube channel featuring numerous recordings with mbira players in Zimbabwe. This is a great place to start understanding the transcendent beauty of mbira. Also see the Zimbabwe Mbira YouTube channel.

Clip of an impromptu outdoor mbira performance posted by Albert Chimedza, maker of Gonamombe mbiras at #thembiracentrehararezimbabwe

https://www.instagram.com/p/B2_zpq8DdGP/

An hour-long podcast program about Hugh Tracey’s legacy featuring excerpts from many recordings and reflections from African musicians today.

Kalimba Magic is an extensive website and blog dedicated to the promotion of the kalimba (in the generic ‘thumb piano’ sense of the term), run by an ex-radio astronomer in Tucson, Arizona.

The International Library of African Music home page at South Africa’s Rhodes University.

How to make a mbira