Kawashima Textile School building in Kyoto

Helen Ting talks to Emma Omote about her role in keeping the ancient craft of kasuri weaving alive and asks: how resilient is this specialist craft skill in the age of machinery and mass production?

Emma has taught kasuri (also known as ikat) for 11 years at Kawashima Textile School in Kyoto. Kasuri involves the painstaking skills of individually binding bundles of warp and / or weft threads by hand to create sections that resist dye. After dyeing, the threads are carefully re-arranged on the loom to create a pattern for weaving. At Kawashima Textile School, Emma teaches local students who come to Kawashima from all around Japan for a two-year hand weaving course and many overseas students for short courses.

Kawashima Textile School was established as a gift to the community nearly 50 years ago by Kawashima Textile Manufacturers Ltd. (now Kawashima Selkon Textile Co., Ltd.), a textile company whose history goes back to 1843 and includes exhibiting a prize-winning tapestry at the 1889 Paris International Exposition. Today, Kawashima Selkon produces both mass-produced modern and traditional handmade textiles.

In this article, Emma talks to Helen Ting from Australia who was one of Emma’s overseas students.

Emma weaving a kimono at home. The double-beam counterbalance loom was made by a local loom craftsperson who has since retired.

The impact of COVID-19

First of all, how has COVID-19 affected teaching at Kawashima Textile School?

Since we only have a small number of students this year, we are able to continue teaching, with precautions. In Japan, we are already used to wearing masks and sanitizing, so that is not a problem, but it is difficult to break habits when teaching, such as getting close to explain something, touching the same tools.

Sadly, we had to cancel our biannual International Student Courses. We have always had around ten international students per semester, so we miss them very much.

We are trying to do what we can in this situation, and are using this opportunity to focus on collecting information and writing about our school, since we are nearing our 50th anniversary in 2023.

- Detail of Emma’s first kasuri project (kimono). The overall pattern is made of warp kasuri on top of stripes.

- Emma’s first kasuri project “Tategasuri 《Uroko》(Warp Kasuri 《Scale》)” 2009. In Japan, the traditional Uroko pattern has been used since ancient times, often as a protective charm to ward off evil.

- Two of Emma’s kimonos from an exhibition in 2019 at Somé Seiryukan, Kyoto. Left “Komochigasuri 《Swim》” 2019 Right “Yagasuri 《Tilt》” 2019

Kasuri

Kasuri has a distinctively hand-made look and a random element to it: that fuzzy line can’t be made by a machine and can’t be fully controlled by the hand. When I was learning kasuri with you, this was what was particularly interesting to me, trying to get some blurry line but not too much.

Tell me about what is a ‘perfect’ kasuri to you? Is there such a thing?

I think that in this case, perfection is subjective. To me, a good kasuri is one that does not get in the way of what is trying to be expressed. One very misaligned thread could bring attention to itself, and not the motif or fabric.

What makes kasuri special to you and why do you do it?

Kasuri is a unique way of creating patterns and colour. I think it is fascinating how the technique itself or the idea of it is very simple, but there are so many possibilities.

When tying the warp threads onto the loom, the threads are adjusted to the pattern, but they will inevitably start shifting. Balancing how much to control and to “let be” is challenging, but I think that is also what makes kasuri interesting.

Is there something different about Japanese kasuri compared with ikat practices in other countries? eg. is it the patterns, what kasuri material is used for, the yarns or dyes, the techniques for making kasuri?

Many countries and cultures have their own beautiful ikat. Kasuri in Japan has developed in different ways with its own styles of warp kasuri, weft kasuri, and double (warp and weft) kasuri. There are also several different techniques for creating patterns on the threads, such as kukuri (binding), itajime (board-tightened), orijime (weave-tightened), surikomi (scrubbed/rubbed in), and so on.

There are many different types of kasuri across different regions in Japan. For example, in Kyoto we have Nishijin Gasuri, which is often a colorful shifted warp kasuri on silk.

Kasuri is time-consuming, but as a kimono, it would usually be classified as casual wear. I think it’s interesting that the time it took to make, or the money spent by the buyer, does not change the rank it is in.

Ikat has travelled or has been invented around the world, and I suggest people look into the ikat of their own region or culture. They have all developed in beautiful ways in accordance with the various cultures, climates, and lifestyles.

- The dyeing process.

- Sections of the bound kasuri warp ready to be overdyed.

- “Drum seikei-ki” which translates to “drum warping machine.” The warp is wound onto the “drum,” then wound (beamed) onto the beam (usually the beam on Japanese looms are detachable/removable). By using this, a repeat pattern in the length of the drum’s circumference can be made.

Keeping the kasuri tradition alive – why and how?

How did you learn kasuri? Where and who from?

I learned weaving and kasuri at Kawashima Textile School, where I now teach. My first kasuri project was a 16-meter long warp kasuri kimono, which was ambitious!

I feel like I have learned, and am still learning, so much through working as a teacher. I started out as an assistant to Kozue Yamamoto (now our director), who teaches kimono and obi weaving. I had the opportunity to see not only how different designs turn into fabric, but also mistakes and accidents, and how to handle and avoid them. It is important to take care not to make mistakes, but also to know what to do when they happen.

What do you think attracts students to learn how to make kasuri?

I can’t speak for everyone, but I feel many of our students are very conscious of modern consumption. The long creating process for kasuri, and the natural shifting of the threads that is not in our control, resulting in a unique, blurry image, could be what we feel is missing from our everyday lives right now, where we are surrounded by modern technology and mass-produced items. I think many of us enjoy having personal connections with objects and want to know and experience more of the process of making things with our own hands.

Why do you think it is important to keep this craft tradition going?

Many techniques have been lost over the years. A famous one is Tsujigahana, which is a shibori and dyeing technique.

By sharing the kasuri technique, more people around the world will know about kasuri, and we will always have people who can pass on the knowledge. The students that I teach may change and adapt the technique to fit how they prefer to create, but I like the thought of helping to spread seeds around the world.

I had the pleasure of teaching a student from Estonia, who was doing research in Estonian double ikat. It had existed around 1885 to 1920, but sadly, the technique had not been recorded very well. The idea of taking part, however tiny, in de-mystifying the technique, and the hope of it becoming known again, was very exciting.

Kawashima Textile School is a very inspirational place to me and to many former students. It’s rare to find a place dedicated to full-time study of hand weaving. How does the school contribute to the continuation of kasuri? For context, are there other institutions that teach kasuri in Japan? If so, how are they different / similar?

Some art schools with textile departments teach kasuri, but many of them have been downsizing or closing due to the declining number of the young generation in Japan. For non-Japanese people, there are opportunities to study at these schools as a foreign exchange student, but if you are not a university/college student, Kawashima Textile School is a good option.

From what I know Kawashima Textile School is the only school of this scale in Japan specializing in weaving. It is probably also the only school in Japan that teaches Kasuri as an intensive course in English.

I’m interested in the concept of adaptation and resilience regarding teaching traditional crafts. Do you think kasuri is a resilient craft that will adapt and remain relevant? Are you optimistic about the future of this technique?

I think the key to resilience is people understanding the beauty and value of something. There are so many people around the world who are interested in this technique (including kasuri and ikat from their own country/culture), and it is encouraging. So far I have taught students from nearly 30 countries. Many of our students are from Sweden, since we have a partner school there (Handarbetets Vänner Skola). The number of students from Australia has increased in the past few years, and they are the second largest group of overseas students after Sweden. Last year we had students from Australia, Canada, China, Colombia, Estonia, Ireland, the UK, the USA, Singapore, and Sweden.

I think our job as makers and teachers is to hand down our knowledge to the next generation. If not, how would someone know to wear a kimono with the appropriate motif for the season, and why that is important?

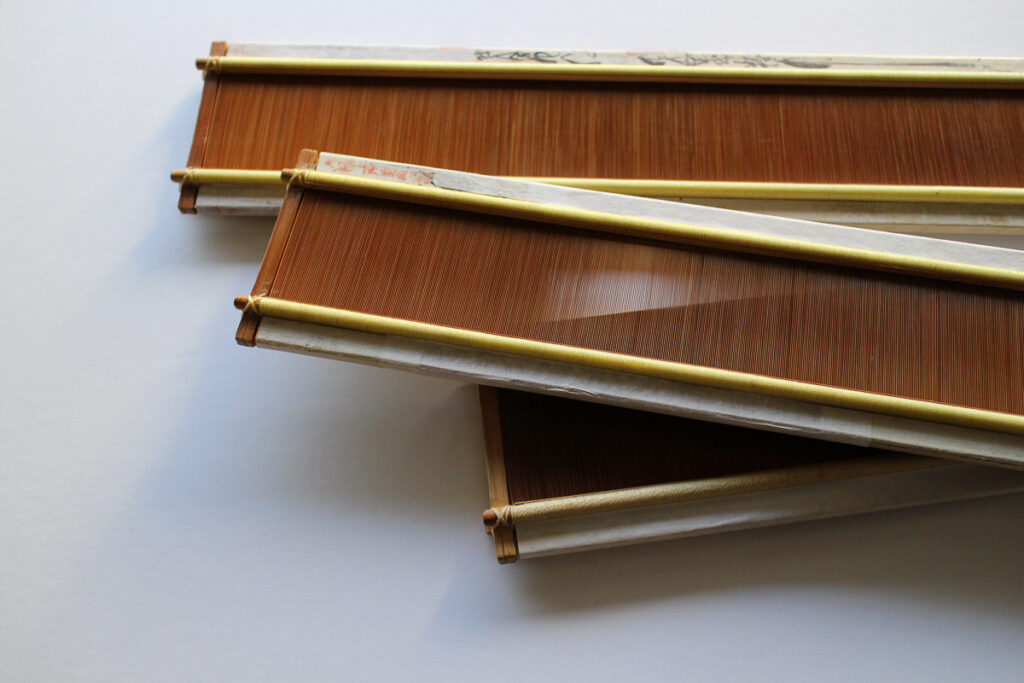

- Fine bamboo reeds at Kawashima Textile School which separate warp threads and help ‘beat’ the weft thread when weaving, which students use with care. They are lighter than most modern loom reeds which are made of metal.

- Fine bamboo reeds at Kawashima Textile School which separate warp threads and help ‘beat’ the weft thread when weaving, which students use with care. They are lighter than most modern loom reeds which are made of metal.

The future

What changes are you seeing in teaching kasuri? What challenges does teaching kasuri face over the next while and what strategies are you adopting to these?

The number of people showing interest in learning kasuri has grown since around the late 2000s. The internet has helped a lot to spread the word about our school, and we are grateful to our former students that have contributed to this.

As for challenges, this applies to handweaving in general, but many craftspeople and business owners are aging and retiring, without successors, so we are losing high-quality tools and materials such as threads. One famous example in the textile community in Japan is the bamboo reed. There were different craftspeople that specialised in the different stages of production. When one of them passed away, they could no longer make the reeds anymore.

I think what we can do is spread the word and share, so we can support small businesses with good products. We are also working with younger craftspeople who do woodwork, to help build simpler tools for us.

Helen Ting is a handweaver from Sydney, Australia who is interested in traditional craft and textiles.