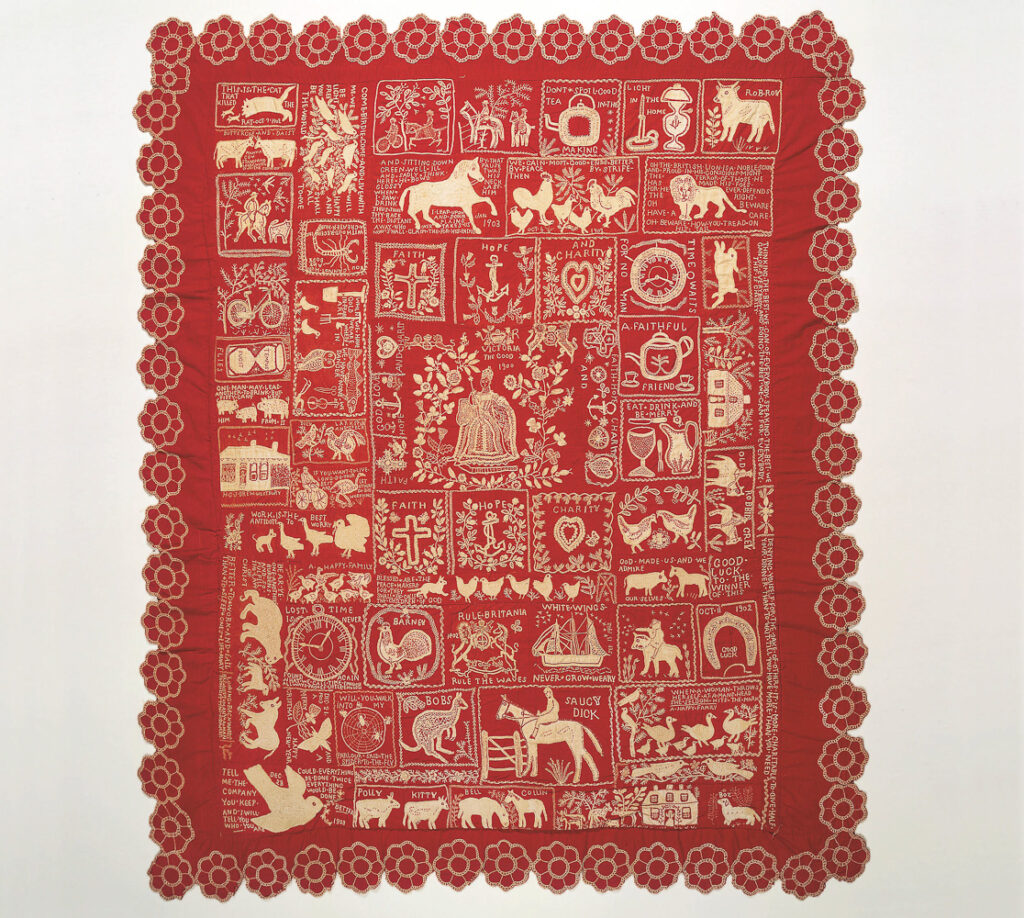

The Westbury Quilt, 1900–1903 Tasmania, cotton, 223 x 191 cm

This patchwork and appliqué quilt is embroidered in the medallion style with red cotton squares sewn together with thick white thread in a raised technique – a reversal of the usual red stich on white. The central panel features an embroidered portrait of Queen Victoria, with roses, thistles and shamrocks symbolising England, Scotland and Ireland. The Misses Hampson (Jane and Mary) worked the quilt on their farm, hence its imagery of cows, horses and roosters – all with pet names. A lone kangaroo indicates its Australian origins. The imagery is assured in its observations of family and farm folklife, the identification of its makers with Britain, and their moral preoccupations.

Purchased through the Australian Textiles Fund, 1990

Stephanie Radok fondly reviews Noris Ioannou’s Vernacular Visions, a history of folk art in Australia.

Noris Ioannou, Vernacular Visions: A Folklife History of Australia: Art, Diversity, Storytelling, Wakefield Press, 2021

Vernacular Visions is a wonderfully heavy book in more ways than one as it has both physical and intellectual weight. Beautifully designed with thick paper and fabulous illustrations, it takes on a very big topic with grace and tons of research. As history, it records and connects, contextualises, analyses and brings to light what may otherwise not be seen. Who knows what it may inspire?

Curiously the book that preceded it on roughly the same topic though focusing much less on material objects. The Oxford Companion to Australian Folklore published way back in 1993 has on its front cover the very same work that Vernacular Visions has on its back cover.

This is The Westbury Quilt made in Tasmania by the Misses Hampson (Jane and Mary) from 1900 to 1903 and in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia. It includes an image of Queen Victoria, a teapot, many named farm animals and mottoes as well as a kangaroo. It asserts a British ‘civilisation’ on the farm. It is a humorous, highly resolved, decorative work, red and white and joyful.

Both Vernacular Visions and the Oxford Companion put forward Aboriginal art as the first and ongoing folk art of Australia. This is a good move: to not begin with the more recent migrants is to stir all Australian folk in together and openly support the benefits of cross-fertilisation and co-existence.

Examples of Aboriginal art used in Vernacular Visions range from rock paintings to masks made from recycled materials, the Toas, Ernabella pottery, and artworks by Ian W. Abdullah, Pantjiti Mary McLean, Harry J. Wedge, Thancoupie, Bluey Roberts, Yvonne Koolmatrie, Ginger Riley Munduwalawala, Janet Watson and others.

Famously in 1994, an Australian gallery was rejected from the Cologne Art Fair for planning to show contemporary Aboriginal art because, they said, it was ‘folk art’. Ioannou discusses and discounts this approach. It’s complicated but suffice it to say that art borders have moved on since 1994 and Aboriginal art, unlike any other indigenous art in the world, is today shown in contemporary art places globally.

As with life, there is no recipe for folk art. Defining folk art/folklife is a moveable feast that dips in and out of rules and boundaries. Folk art, vernacular art, naïve art, outsider art, making do, popular art, bush mechanics, art of the people, low art, the disregarded and disinherited, all these categories merge and blend. Defining qualities such as ordinary, domestic, traditional, functional, regional, low status, local, relaxed, basic, spontaneous, religious, inventive, obsessive, accidental, provincial, coarse, crude, common, swirl around.

It is salutary to think of all of them as involving vision and visions. Ioannou emphasizes that tradition is not something fixed:

“Rather than being a restraining force, tradition can be a dynamic, accommodating impetus for the interpretation of past patterns of belief and thought, hence acting as a springboard for creative expression.”

Vernacular Visions has an endearing though not exclusive focus on South Australian examples thus while not excluding the rest of the country it does rock the boat of internal Australian provincialism.

Ioannou’s previous research and publications on German ceramics and furniture in the Barossa and Adelaide Hills is a strong element as well as other regional examples of isolated individuals like painter Iris Frame down in Penola. Many South Australian readers will find childhood memories in the book such as the water garden made by Germano Capaldo in the city of Adelaide, or the cactus garden by Joseph Lowey that used to be seen on the way to Port Wakefield.

Yet a glowing example of a folk artist—Arthur Stace who wrote Eternity in chalk all over Sydney—does not appear in Vernacular Visions. But then the Loch-Eel of Lochiel is missing too.

Vernacular Visions is not exhaustive as it would not be possible to encompass all the folk creativity in Australia. Big Things do get a look-in as do many brilliant examples of application and creativity. The chiffonier made by Maude Baillie in 1904 on Wedge Island, with a penknife and chisel, is astonishing.

Another memory arose as I read Vernacular Visions when I recalled the pincushions that my mother made for me from felt. One with my initials on one side and the year on the other, and one that was a sort of wild lizard-like animal whose head was later chewed off by a jealous dog. Were they folk art? I suppose so, as well the tablecloths and handtowels she embroidered. Maybe we are all potential folk artists.

Ioannou discusses the multiple categories and distinctions and reasons for folk art: affection, need, desire, obsession, with a broad analytic sense of history and sociology. It’s a lot to think about. Learn about Zilm Chairs, Bosleyware, recycling, foreignies and shell gardens. A book for your coffee table, a reference work, an inspiration to think freshly and freely about where you are.

Stephanie Radok