Piña (Pineapple fiber) cloth weaving; photo: Edgar Alan Zeta-Yap; https://www.flickr.com/photos/eazy360/3900179368/in/photostream/

Simon Ellis finds that piña weaving not only preserves a priceless cultural heritage but also mitigates the impact of climate change and flooding in downtown Kalibo.

Piña is a traditional Philippine fabric made from the Spanish red pineapple and was used for formal dress from at least the nineteenth century (Respicio 2014). The thread used for weaving is fine but very tough.

The centre of piña production is the province of Aklan on the island of Panay in the central part of the Philippines. Because piña production is supply-constrained, production has spread to other parts of the Philippines including the neighbouring island of Palawan, and to other countries in particular Indonesia and Honduras. In addition to this ‘threat’ piña suffers from low wages, climate change and ‘dilution’ through mixing with other fibres. Further related issues concern the loss of high-level skills and the risk of cultural appropriation. Piña fibre is also passed to other manufacturers throughout the Philippines, where it is used in a variety of high-value fabrics including by high fashion designers.

This study describes the results of a Census of all piña workers in the city of Kalibo, the capital of Aklan province, and the heart of piña production. In particular, it argues that increased piña production would increase the level of sustainable development including progress towards the SDG targets of

- Goal 4 – traditional and sustainable skills, related to community development and cultural diversity

- Goal 8 – decent work and cultural production for tourists

It presents evidence that support for piña production would reduce flooding and the impacts of climate change in Kalibo, where typhoons and flooding of the city centre, experienced since at least the early twentieth century, have become a regular threat every few years. In short support for this candidate for UNESCO’s Intangible Heritage list[1] has the capacity to mitigate climate change, and save a cultural icon from extinction.

The Survey

In 2018-2019 a census of piña workers took place in the city of Kalibo. The survey was undertaken by Custom-made Crafts/Non-Timber Forest Products group. It was financed by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA). The survey interviewed 400 people including weavers and other family members involved in production, as well as entrepreneurs with a local base. Data consisted of a survey questionnaire the findings of which were supplemented with several focus groups. Weavers operated from their homes and so visits to their homes allowed a comprehensive inventory of weaving-related equipment and GPS locations were taken to map locations by ‘barangay’ (neighbourhood).

Data from the national labour force survey for 2016-7[2] show that over 50% of rural textile workers are over the age of 50, and overwhelmingly women (Figure 1). A similar profile emerges from the Kalibo survey, despite the relatively young age profile of Aklan province. The immediate risk to piña weaving from a lack of younger weavers is apparent.

Note; different reference years reflect data availability. Aklan population from national Census.

The weavers in the Kalibo survey reported that 60% of them learnt from a family member. Many respondents reported that they started learning at the start of primary school, though they expressed nervousness about the issue of child labour. Traditionally knotting the fibre to create the yarn has been the activity of the younger members of the family. In common with many producers of traditional crafts throughout the world the respondents report disinterest amongst the younger generation who they felt were ‘distracted by technology’, but some expressly did not want their daughters to follow them as a ‘weaver lang’.

Several of the ‘entrepreneurs’ had given up weaving in their youth, and then returned to it in later years, out of nostalgia and a wish to support their traditional skills. This process was known as ‘balik-balik’ or ‘give/go back’. The survey found that though 54% said they could teach others only 5% said they could produce designs, and very few weavers could weave the finest piña (liniwan). Designs were normally provided by the entrepreneurs rather than coming from the weavers themselves.

Focus group discussion suggested that weaving was seen as little more than a source of income. They were unaware of the cultural significance of piña. They had no interest in owning any piña and felt that it was just for rich people ‘pang-mayaman lang ang piña’, and they would have no use for it ‘wala naman silang pagsusuotan’.

In sum, piña is produced by an ageing female workforce. In general, they undertake the work to increase household income. Though weavers learnt in the family from an early age the average age to start weaving was found to be 20, an age when an independent income is often desirable. The majority of the weavers were worried about the decline in skilled knowledge, but would prefer it if their children went into more lucrative work. On the other hand, several of those who had learnt weaving when they were young and then taken up other work, had returned later in life as they appreciated this important cultural icon of their hometown.

Piña production in the local environment and the mitigation of climate change

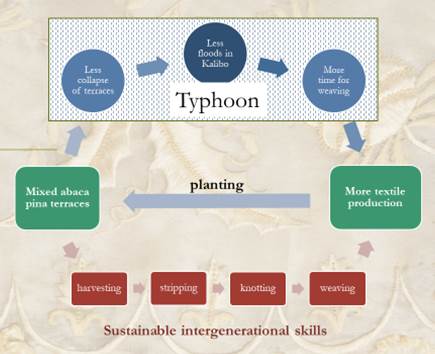

In this section the production process for piña is explained, including why it is difficult to mechanise, how thus its production is a sustainable craft, and how indeed increased piña production in Kalibo would not only increase sustainable production, but also how expanding production would mitigate the impact of climate change by reducing the level of flooding in the city.

The process of piña manufacture involves a lengthy series of tasks that are not easily mechanised as they require careful examination and manipulation of the pineapple fibre (Respicio 2014).

- The leaves of the pineapple are harvested and dried

- The leaves are scraped to remove the fibres. Traditionally they are scraped with a ceramic shard. The finer innermost fibres ‘liniwan’ are preferred to the coarser ‘bastos’.

- The dried fibres are knotted to create a thread. This is a laborious process and the ‘entrepreneurs’ felt that it was one of the main limitations on the quantity of piña produced.

- The thread is woven into plain fabric or specific designs, sometimes it is woven together with silk to create piña-seda. The weaving normally takes place on a handloom. Almost all the weavers used an upright loom, driven by pedal or perhaps a small motor.

Steps 1 to 3 in particular have proved difficult to mechanise, and most piña is woven in the homes of weavers or at the premises of small companies or collectives. The majority of weavers learnt their skills as children by watching others.[3] The fabric produced passes to ‘entrepreneurs’ who may be the owners of small local weaving centres, or they may ‘organise’ local weaving households.

The process of piña production is closely tied up with climate change and the local environment. The Philippines has long been subject to typhoons and flooding,[4] and now experiences about twenty serious storms in a year. Typhoons can occur at any time in the year, but most commonly in June to October. Figure 2 shows the weavers’ reported activity by month throughout the year. This suggests that typhoon season largely coincides with the low point in piña production, which tends to gear up for the Christmas period at the end of the year. The end-of-the-year season of high demand reflects both present giving and a large number of more formal settings whether religious or family-centred.

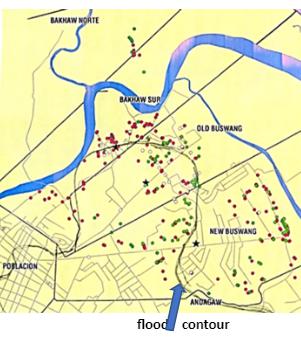

- Figure 3. Piña production and climate change. Maps (A) planting areas for piña and abaca, and (B) downtown Kalibo with piña workers houses in relation to flooding; highest risk to the right of black curving line contour marked by a blue arrow. Maps by Kalibo Piña Survey.

Some weavers reported being forced by managers (‘amo’) to carry on working to meet orders when their houses were flooded. Figure 3 shows the official high-risk flood contour running through the center of Kalibo. Red and green spots mark the location of the houses of piña workers. It can be seen that a large proportion of them are at very high risk from flooding. [5] During the focus group discussion the entrepreneurs remarked that the weather can be a problem for weaving piña – not ‘mainit’ (hot) because the fibres will be brittle, and not ‘maulan’ (rainy) because the fibres will be damp and ‘dikit dikit’ (sticky).

The red pineapple for piña, and ‘abaca’ known as ‘Manila hemp’, used for traditional textile production in Kalibo are grown in the hinterland of the city on both sides of the Aklan River (Figure 3, Map A.) A geological study (Catane et al 2012) into landslides in a 2008 typhoon demonstrated that flooding in Kalibo was exacerbated by field terrace construction in this valley in the hinterland of the city. The construction of the terraces meant that they ‘pooled’ rainfall, until a point at which the terrace ‘burst’ causing landslides and raising the level of the river as it flowed into Kalibo. Chuxiong et al (2021) have conducted an extensive in-depth review of field terraces in several different regions of the world. They conclude that while in the right circumstances, terraces can conserve soil nutrients and retain water, in the wrong circumstances they can be counter-productive. They suggest that terraces need to be carefully constructed having regard to the local environment including rainfall, water run-off, soil and surface geology etc. They point out that local terrace systems were not designed for modern large-scale mechanised agriculture and suggest they should be maintained using traditional sustainable methods. They summarise that ‘landslides and mass movements caused by poorly designed terraces are frequent.’ If terraces are not level this can lead to ‘gully’ and ‘rill’ erosion, water pools form, and may suddenly be released, in exactly the same way suggested in the study of the 2008 flood on the Aklan river (Catane et al 2012).

This hinterland of the Aklan River is the area from which the weavers obtain their supplies of abaca and piña as shown in Figure 3 Map A. Abaca, in particular, is farmed in extensive plots for pulping into paper. Specialists in traditional textile production say that the fibre used for weaving is superior in small-scale mixed cropping, whether because of the care taken in cultivation or because of the semi-shaded environment of a mixed plot.[6] During the stripping of the pineapple leaves for the preparation of the fibre it is vital that workers are able to distinguish the coarser ‘bastos’ fibres, from the finer ‘liniwan’. It can thus be argued that a return to small-scale, or mixed, cultivation of piña and abaca would produce both better quality piña and reduced flooding in Kalibo.

The distance travelled to collect raw materials was collected during the survey by the administrative unit rather than by miles/kilometres, but a clear pattern nevertheless emerges (Figure 4). It can be seen that the vast majority of raw material for weaving is obtained within the district (barangay) falling off rapidly to the Kalibo municipality, and then the Aklan province. The rise in national supply clearly reflects local scarcity as well as the benefit of buying in Manila. In the retail world, the form of distance decay curve that this represents is associated with ‘convenience’ shopping, as opposed to traveling to a regional centre such as a larger grocery store or supermarket.[7] While the precise applicability of such a model to Kalibo may be debated the pattern establishes a further element of local supply and sustainability in production, as well as supporting the link to the local eco-system of the Aklan river valley.

In sum, the best piña requires detailed knowledge of growing conditions, as well as how to harvest and strip the leaves from the plant. Mixed small holdings, rather than expansive mass farming, seem to produce the best fibre. Moreover, there is evidence that, by reducing runoff during typhoons, such farming will mitigate flooding in downtown Kalibo, further improving working conditions for piña and other workers. This is not to diminish arguments about the economy of large-scale planting along the Aklan valley, but rather about improving the quality of piña, the working conditions of the workers, increasing sustainability, and mitigating the impact of climate change that is resulting in increasingly frequent typhoons.

The overall pattern of sustainable piña production is summarised in Figure 5. Though piña is an iconic national cultural product, its production is rooted in a local sustainable production (Ellis and Lo 2018), that can enhance the local environment by mitigating climate change.

Working conditions

The piña workers of Kalibo are highly dependent on the ‘entrepreneurs’ known as their ‘amo’, and working conditions raise further issues about the sustainability of piña production. The ‘amo’ is responsible for

- Purchase of raw materials. Sometimes the raw materials are provided directly by the ‘amo’ and the cost is often deducted from the weavers’ wages. In other cases, the weavers buy the raw materials from the ‘amo’ and split revenue from the sale of the product in a system known as ‘agsa’.

- Determining the design the weavers follow

- Financial loans ‘piña pautang’ or credit ‘utang’ and other forms of support for the weavers and their families

The entrepreneurs, or ‘amos’, feel weavers often withhold some of the piña fibre for their own purposes, thus reducing the quality of the final product. They also feel betrayed if weavers seek to change their ‘amo’. The weavers feel unduly controlled by their ‘amo’. They feel they are ‘nahihiya’ and cannot pay their credit. The relationship between the ‘amo’ and the weavers is both closed and contested, with neither side consistently ‘in the right’. A more objective evaluation of the situation may be obtained by looking at the evolution of the value chain for piña from the 1980s to 2019 (Figure 5).

The entrepreneurs, or ‘amos’, feel weavers often withhold some of the piña fibre for their own purposes, thus reducing the quality of the final product. They also feel betrayed if weavers seek to change their ‘amo’. The weavers feel unduly controlled by their ‘amo’. They feel they are ‘nahihiya’ and cannot pay their credit. The relationship between the ‘amo’ and the weavers is both closed and contested, with neither side consistently ‘in the right’. A more objective evaluation of the situation may be obtained by looking at the evolution of the value chain for piña from the 1980s to 2019 (Figure 5).

Evolution of the piña value chain 1987 to 2019

Figure 6 is composed from a variety of different sources.[8] The piña data for the most part come from surveys, but some data on prices come from administrative sources. The different conditions under which the data were gathered make precise comparison risky but several general observations may be made. Firstly, the price of pure piña has risen faster than piña /seda (piña /silk) mix and faster than the wages paid to all those involved in preparing the fabric. This picture aligns with the survey findings to the extent that the entrepreneurs stated that demand for piña outstripped supply. Given this it would also seem to support the story given by the weavers in that the wages paid to them have hardly changed in twenty years, whereas the value obtained by the entrepreneurs has risen much more. The entrepreneurs would claim that this should be seen in relation to mounting costs in transportation, marketing etc., but there seems little doubt that at least some of the increased value (i.e., the price obtained by entrepreneurs on sale) should have been passed on to the weavers. Indeed, in some cases, the amount of money paid to the worker is a little different to that of buying the raw pineapple.

Figure 5 should also be read, as the entrepreneurs suggest, as a reflection of unmet demand. The need for processing by hand, and the impossibility with current technology, to effectively strip the piña leaves to separate off different qualities of fibre, and the need to knot the fibres by hand, in particular, represent the main blocks to a larger supply. Under these circumstances it is not surprising that piña production has spread from Aklan to other parts of the Philippines, and indeed to other countries.

Thus, while it seems reasonable for the entrepreneurs to say that the high price reflects supply constraints of lack of weaving skills and time taken in knotting, thus unmet demand, it seems reasonable to say that a fairer distribution of the income towards the weavers and knotters would encourage further people to take up weaving, especially as those who weave say it is largely to provide an income for their families.

Conclusions

This paper began by introducing the piña workers of Kalibo noting that they are older women and highlighting the consequent risk of losing the production of this textile that has been an icon of Philippines culture for over 200 years. It went on to demonstrate the close association of its sustainable production process with the local environment in terms of the skills to identify the best fibres through the use of locally transmitted manual skills and knowledge. It argued that further attention to quality piña and the best ways to grow it would have a positive effect in mitigating the impact of climate change and flooding in downtown Kalibo. Finally, it has been suggested that contested relationships with the entrepreneurs who market the finished fabric could be addressed by redistributing some element of sales revenue.

There are thus two major recommendations

- Piña production should be supported by encouraging small-scale mixed cultivation of pineapple and abaca in the Aklan River valley. This will mitigate flooding in Kalibo, improve the quality of the textiles and improve working conditions for the weavers

- Some element of sales revenue from piña should be redistributed to the weavers to motivate young people in Kalibo to take up piña production.

These recommendations will directly contribute to the Philippines’ progress towards Sustainable Development Goals Target 4.7 – on fostering skills for sustainable development and cultural diversity, and Target 8.9 – concerning decent work and local cultural production. They will also address Goal 13 on mitigating climate change.

Simon Ellis is a regional advisor for UNESCO and a craft research consultant: link linkedin.com/in/simon-ellis-76b2191b/

Acknowledgements

The Kalibo Survey was carried out by Custom-made Craft, and the observations herein were collected by, among others, Beng Camba, Benjamin Malihgalig, Kitty Caragay, Tanya Lat, and I am most grateful for their friendship and for allowing me to help with the survey. Any misinterpretation of the results is my fault, not theirs. I am also very grateful to Andy Moran, as well as to Myke Gonzalez of City University San Francisco for further discussion on Philippines textiles. My work on craft in the Philippines has also had the support of Prof Dennis Mappa, of the University of the Philippines at Diliman and National Statistician of the Philippines, as well as Celia Elumbe previously Director of the Philippines Textile Research Institute, and many colleagues at the National Council for Culture and the Arts especially Marichu Tellano. The work of Aklan Province and the Municipality of Kalibo in support of piña production must also be acknowledged.

Bibliography

Catane, S., Abon, C., Saturay, R., Mendoza, E., Futalan K. (2012) ‘Landslide-amplified flash floods—The June 2008 Panay Island flooding’, Geomorphology 169-170 (2012) 55–63.

Chuxiong Deng, Guangye Zhang, Yaojun Liu, Xiaodong Nie, Zhongwu Li, Junyu Liu, and Damei Zhu (2021) ‘Advantages and disadvantages of terracing: a comprehensive review’, International Soil and Water Conservation Research 9, pp. 344-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2021.03.002

Respicio, N. (2014) Journey of a Thousand Shuttles: the Philippine Weave, NCCA, Manila.

Teodosio, I., and Teodosio M. (2006) ‘Field Planting and Management of Tissue-cultured Aklan Piña ’, ASU TechnoUpdate, June 2006.

Coronas, J., (1930) ‘The first typhoon over the Philippines in 1930: April 18 to 19’, Monthly Weather Report, April 1930.

Ellis, S., and Lo, J. (2019) ‘An economic assessment of Asian crafts’, in A. Mignosa and P. Kotipalli ed. A Cultural Economic Analysis of Craft, Palgrave, pp.167-184.

Gonzal, L. (2007) ‘Integrating Abaca in a Mixed Forest Culture: A Livelihood Option for Smallholder Tree Farmers’ Annals of Tropical Research 29(3): 15–24.

[4] The first recorded typhoon recorded in detail would seem to have been in April 1930 (Coronas 1930)

[5] The Municipal Flood Hazard Map (?2015), p.15 para 2.10 indicates that in the right-hand half of the map (beyond the black flood contour line) there is ‘Very High flooding susceptibility –area likely to experience flood heights of greater than 2 meters and /or flood duration more than 3 days. These areas are immediately flooded during heavy rains of several hours, include landforms of topographic lows such as active river channels, abandoned river channels and are along river banks, also prone to flash floods.’

[6] This information comes mostly from informal comment but discussion for growing conditions of red pineapple and abaca can be found in Teodosio and Teodosio (2006), and Gonzal (2007).

Respicio, N. (2014) Journey of a Thousand Shuttles: the Philippine Weave, NCCA, Manila.

Teodosio, I., and Teodosio M. (2006) ‘Field Planting and Management of Tissue-cultured Aklan Piña ’, ASU TechnoUpdate, June 2006.