Dorothy Erickson – Piu Di Cinquanta: Celebrating 55 years of designing and making jewellery, Art Gallery of Western Australia, March 20 – June 30, 2024. Photo: Dorothy Erickson.

Philippa O’Brien reflects on the extraordinary career of a West Australian jeweller whose work is inspired by a unique natural environment.

Dorothy Erickson AM has been creating jewellery since 1969. She had been inspired by the gift of an opal from her mother at the time of the opening of a jewellery studio at the new Western Australian Institute of Technology (WAIT, now Curtin University), and by the example of the ground-breaking British jeweller Wendy Ramshaw who was later artist in residence there in 1978. As both a leader of the New Jewellery Movement and as a female artist, Ramshaw was a role model, mentor, and close friend to Erickson, enabling a path to her own international career by the early 1980s.

Erickson is sensitive to place. She has an innate ability to respond directly to landscape, to find its essence beyond its obvious attributes. For her, it is an ever-luminous source inspiring an avalanche of ideas as she takes the expressive, poetic sensation and makes something solid, something real. It is a direct transference from the intense moment of perception to a complete, resolved object – and to endless, artful variations on the concept. As such, Erickson is never short of ideas, but her jewellery wears them lightly; they flow easily and naturally, giving her work a practicality and clarity together with the confidence and consistency of an individual sensibility. In some ways, her process is disarmingly simple. In other ways, it is saturated by a wealth of hands-on skills and technical experience.

Dorothy Erickson began professional life as a teacher, rising to principal of a primary school before attending WAIT as a mature age student from 1968 to 1971. She had recently returned from living in Europe where she enthusiastically embraced the art she encountered in the great museums, the explosion of new design that was sweeping Europe and her own connections to this from her Scandinavian heritage. Established in 1966, WAIT was in its infancy, and she studied in the new Jewellery and Silversmithing course set up by Francis Gill. The only jewellery student in this four-year Associateship in Art Studies, Erickson was supported by Head of School Tony Russell to find outside practitioners to teach her technical processes, such as casting and stone setting, that were not yet available in the course. Her work at this time was greatly influenced by her country upbringing that had sparked a long-term interest in natural science. She was encouraged in this by her mother Rica Erickson, a well-known naturalist.

Erickson returned to Curtin in 1975 where the Manchester-trained designer and silversmith David Walker had arrived to take up the new position of Head of Crafts. Walker offered Erickson a postgraduate scholarship and a teaching position in which she was responsible for mastering the myriad techniques that a steady flow of visiting artists-in-residences introduced. New materials and skills to which she was exposed included plastics/epoxy resin, etching, parcel gilding, stone cutting, married metals, turning and electroforming, all of which contributed to her own technical toolkit and informed the solo exhibition that showcased her work as the culmination of her scholarship. Roger Garwood’s superb photographs of the collections that made up the show were embraced by the Crafts Council of Australia and widely distributed, quickly establishing a national presence for her work.

Some of this work was inspired by the view from her studio at the top of Jacob’s Ladder overlooking Perth Water. Erickson could see night lights glittering in the city buildings and car headlights making golden paths across the Narrows Bridge and around the park that would later be named in honour of her husband, Town Planning Commissioner Dr David Carr. In response, she literally turned the scene into small art works in the guise of wearable jewellery; each is an elegantly conceived object, delicately balancing naturalism with abstraction within the clarity and formal disciplines of contemporary design. Other works (Perth Water and the Sunrise – Sunset series) had taken inspiration from the sunrise over the Darling Scarp and sunset through the pine trees on her way home from WAIT.

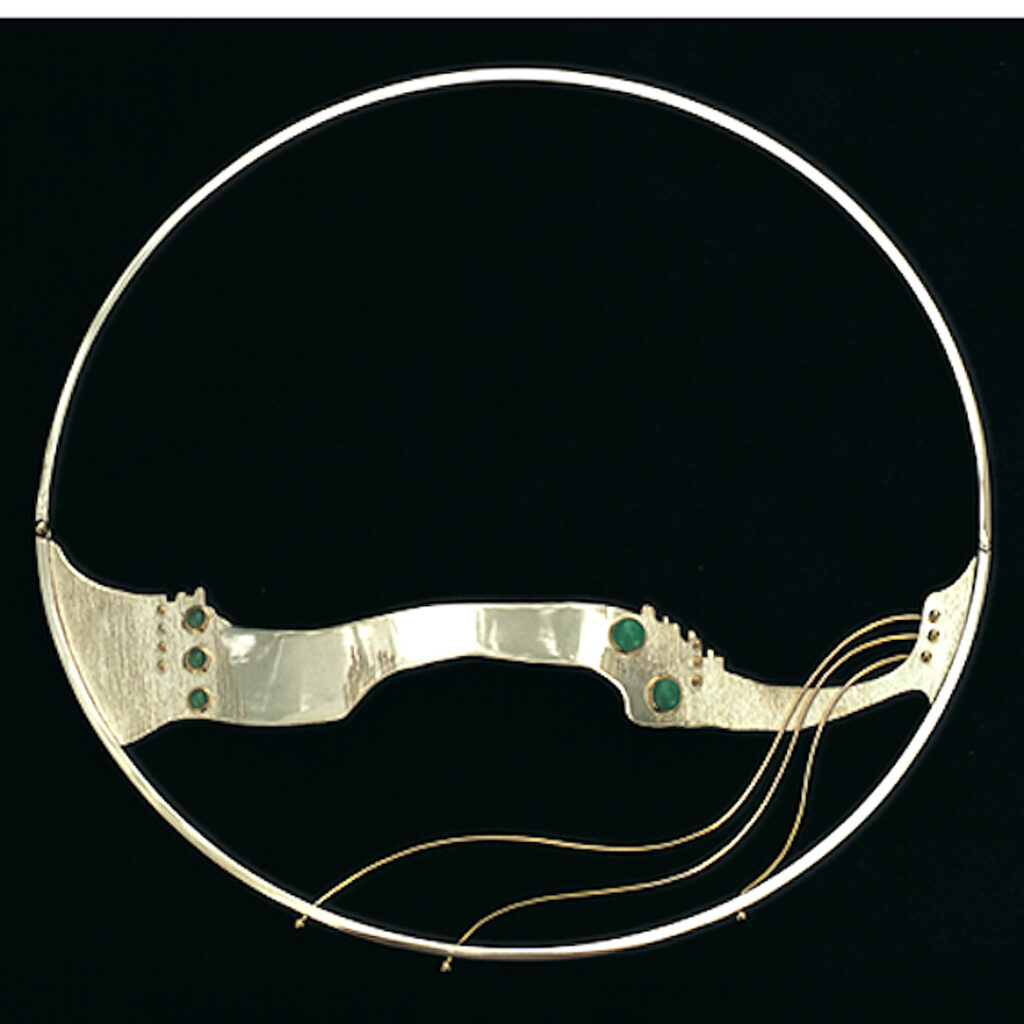

Dorothy Erickson, Perth Water neckpiece, 1981, sterling silver, 18ct gold, 9ct gold, chrysoprase, c. 200 x 200 x 20mm. Exhibited in Schmuck ’82 Tendenzen? in the Schmuckmuseum, Pforzheim Germany, James Collection. Photo: Dirk Wittenberg.

The Noojee series that followed grew from a workshop in a bush camp in Victoria in 1979 with visiting German jeweller and environmental sculptor Claus Bury. The workshop became part of the 1979 film Sculptures in the Landscape that documented one of a series of large-scale sculptural installations Bury made in sites around the world. The way his sculptural structures were imposed on a vast landscape template opened Erickson’s mind to new ways of thinking and she was energised by the encounter with scale that was so different from the miniature world of jewellery. Erickson also responded to the material roughness of the installations, the coarseness of the twine and the roughly cut bush timber.

In Noojee, she distilled this transformative experience by focusing on two elements – the string geometry and the formal rectangular shapes of Bury’s structures – and translated them into a new language. She divided the circle motif she was already using with simple straight lines in the most basic geometry. String by itself is also totally flexible and the softness of its lines was a contrast to the rigidity of the metal circle. Exploring movement between these basic elements, Erickson also began to experiment with kinetic possibilities. For instance, the rigid, circular neck rings were hinged and taken apart to creating separate pieces that interacted with each other on the moving body. One section could be independent from the other in a way that created different juxtapositions and a new vocabulary of movement that countered the body’s own form and contours; the bands of unyielding metal are a foil to the softness and fluidity of the human body.

Dorothy Erickson, Sunset armrings II, V, 1982, sterling silver, 18ct gold, mookaite and 0375 Geometric Fusion bracelet, 1982, sterling silver, 18ct gold, citrine, 9ct gold, Sunrise – Sunset Series. Photo: Dirk Wittenberg.

Like a set of musical variations, Erickson then played through a seemingly inexhaustible suite of subtly changing combinations. Shown together, they underline the sheer inventiveness of the project. From this period of vigorous exploration of a simple theme, some outstanding jewellery emerged, work that found its way into many collections and several important exhibitions. This, and her two previous series did much to establish Erickson’s status as an exemplary artist in contemporary jewellery in Australia as well as on an international stage.

In 1982, Erickson was awarded an Australia Council Grant, which enabled her to travel to the Pilbara. She immersed herself in the natural wonders of the area and returned to her studio to make work informed by its vibrant colours, striking landforms and dramatic, ever-changing light. Key to these pieces are the stones that were later cut to her designs in Germany and used for a variety of pendants, rings, and brooches. These forms coquettishly suspended the stones within carefully drawn metal confines. Ingeniously attached to the rigid metal bands, the brilliantly coloured, luminously polished, and elegantly wrapped fragments of Pilbara rock sit easily on the soft contours of the body, balanced like a counterweight on the moving form. They bring the landscape to the body and place the body in the landscape. There is an elegiac feeling of something of value being passed from artist to wearer, from purchaser to recipient as they elusively touch … or do not touch … the skin. These ‘gifts’ for the body don’t just reflect the Pilbara landscape in north-west Western Australia, they are not just a response to its transcendent colour and all-consuming power; they are made from rock from this landscape and carry the full impact of the maker’s immersive experience of it directly to the wearer.

Erickson gave a presentation of her work at an international conference of the World Crafts Council in Austria in 1980 where she was inspired in turn by inventive jewellery made by the world’s best contemporary designers and makers. Returning to Australia full of new ideas, she began to work with a liberating sense of freedom and a renewed faith in her own capacities. This included embracing new materials she had seen successfully employed such as stainless-steel cable. In particular, she saw a world of possibilities in its flexibility as she drew on traditional knot brooches to make a wealth of small and often witty and amusingly playful knot brooches of her own.

The kinetic possibilities of concentric lines of steel cable on the moving body are endless. Fixed points create a counterweight to the radiating curves that respond to the way the piece is worn; the gently shimmering movement of the curves contrast with the freely moving, often unpredictable, loose ends. Sometimes grand sweeps of coil float over the shoulders, elegantly falling across the back. They are as dramatic to wear as they are in repose on the wall as their linear forms with strong, rhythmic lines like radiating circles in water, seem to wrap the wearer in a dynamic drawing that adapts to the body it adorns, reflecting an inner life as much as an outer shape.

Dorothy Erickson, The Peacock– The Birds Series bodypiece, 1990, stainless steel, gold-plated silver, that can be worn in a multiplicity of ways. Collection of the late Wendy Ramshaw, London. Model Kimberly Field. Photos D. Erickson.

The 1990s series The Birds came about after Erickson was drawn to a Willy-Wagtail strutting and twitching in her garden. Birds from black Cockatoos to Budgies, Corellas and pink and grey Galahs were then wittily analysed and their characteristic movements captured in a series of sensitive and captivating bird-portrait brooches. Here, the stately movement of The Peacock contrasts with the rhythmic bounce of The Firebird, the graceful dancing of The Brolgas and the languid displays of the Birds of Paradise.

To make them, Erickson utilised steel cable, an industrial material that has an inherent memory that carries traces of its manipulation. As with all her work, the wearer becomes a participant in the artwork: for example, walking in high heels provokes a staccato movement while flat shoes produce a more leisurely wave. Indeed, these kinetic pieces can only really be appreciated on a moving body. The movement is determined by the length and thickness of the steel cable, the weight of the cap attached and whether the cable has been interleaved with copper wire. Larger, exuberant body pieces make the wearer truly a participant in the expression of this overtly interactive jewellery, replete with references to the birds that inspired them, almost speaking as the wearer speaks. Jewellery like this not only reflects the identity of the wearer, but literally reaches out to its audience transformed into anything from modest brooches to spectacular, sweeping pieces that embrace much of the body. These pieces were outstandingly successful in Japan where they were shown as part of catwalk exhibitions entitled Artistic Australia staged at many venues over several years in the late 1990s.

In the mid 1980s, Erickson was troubled by repetitive strain injury and Guillain Barré Syndrome-CIDP. A change of career seemed inevitable. With her situation complicated by the breakup of her marriage, she decided to return to academia, undertaking a Master’s Preliminary which was followed by a PhD at the University of Western Australia including time at the Royal College of Art in London. She soon found work as a writer, curator, and art critic. Fortuitously, the Australian Broadcasting Commission was making a series of documentaries on Australian craftspeople and selected her as one of the subjects and, with the help of assistants, she returned to making jewellery part-time. The series featuring her Circles and Spinnaker works was aired repeatedly between 1989-1991 covering the years when she made little work while effectively maintaining a professional presence.

These works exploit the power of simplicity. She worked within her physical limitations making use of simple forms to create a new kind of relatively minimal work. Relying on her highly sophisticated design sensibility, the continual paring back heralded a stage of daring simplification that amplifies pleasure, tension, and the beauty of these pieces. Their sense of balance, with all elements reduced to an elemental state, became an increasing presence in her work, imbuing her practice with a breath-takingly composed energy.

Already embracing Australian nature in her series The Birds, Erickson moved effortlessly to rippling water. This new series focused on the beach, the rockpools, the sea creatures, and the sea environment. Specifically inspired by the gentle pulsing of an anemone, the first step into this new arena was in the form of some charming sea anemone pieces, tentacles elegantly spilling from exquisitely arranged Pan Pipes and cast seashells, each tipped with prettily coloured gemstones. It’s important to note that as vital as her observations are to the creation of such works, they also bring together the strength and the fragility, the sophistication, and the innocence, as well as the dewy freshness she finds in her materials. Indeed, her materials are often at the centre of her practice as it is often their specific qualities that inspire an idea: the exploration of its material possibilities lead her to meaning, metaphor, and emotion.

Dorothy Erickson, Fulfilment Ring IV, 2005 18ct gold, iolite. Collection of the Swiss National Museum in Zurich. Exhibited in Homage to Klimt at the Jam Factory Adelaide. Photo: Dorothy Erickson.

Since her first visit to Vienna in 1980 – when she attended the World Crafts Council Conference and saw superb exhibitions of contemporary jewellery in the Kunstlerhaus, the famous Secession Building and other venues – Erickson has found enormous inspiration in exploring the cultural treasures of the city. Her personal friendship with Erika Leitner meant that she had an erstwhile home and studio in Vienna where she could work for months at a time. She exhibited regularly in Vienna, keeping in touch with other contemporary jewellers and exploring the cultural riches of a great European centre.

The ambience and architecture of the city, the museums, galleries, and the many Secessionist influences, such as the U Bahn stations and the great Secession building, eventually led Dorothy to a serious exploration of the work of Gustav Klimt in 2003. The trigger to express her admiration for his painting in the form of jewellery came however, from another source: the sudden availability of small multicoloured precious stones with geometric cuts reminiscent of the mosaic tesserae Klimt had seen in Ravenna and Venice and used to great effect in his own art. Erickson was particularly drawn to Klimt’s more ordered and visually restful works where clear forms sit beside ornately patterned areas often illuminated with gold leaf. Her sketch books from this period contain designs based on over 30 paintings including Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze in the Secession building where multicoloured gemstones are set in gold, a lustrous, malleable material to which she has long been drawn. While the Homage to Klimt series sees her look away from Australia to Europe for creative fuel, Erickson has family connections to gold and the Western Australian goldfields where her grandfather had a gold mine and something of this history comes through in these fine glimmering works.

Erickson studied botany as part of a teaching degree in the 1950s and, during her years overseas in the 1960s, enrolled at the Chelsea Institute in London while researching Australian plants at the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew and the Natural History Museum for her mother, Dr Rica Erickson. Her interest in the minutiae of nature never waned but it was in the second decade of the 21st Century when she was commissioned to write A Joy Forever: The Story of Kings Park that she turned her attention to Western Australia’s unique wildflowers as a subject for her jewellery, making art works to honour Rica – a world expert in West Australian orchids, trigger plants, carnivorous plants, and birds and a highly respected botanical artist with many publications to her name. Because of this, Erickson grew up in a family where natural science – a study of the plants and animals of the bush – were bread and butter to her and her siblings. Examining, recording, and publishing natural science was commonplace, and participating in these intellectual and artistic activities on a national and international scale was part of her everyday life.

Erickson’s Wildflower jewellery emerges from this upbringing as she combines Rica’s botanical drawings as much as observation of actual plants. Rica’s plant depictions are clear, accurate and unembellished, but they are also full of life and have a lightness and luminosity, combined with absolute simplicity and austerity – as well as a sense of naturalness, of wildness, of natural grace. The jewellery that emerges reflects these qualities while liberating Erickson’s exquisite skills and creative sensitivity in her use materials.

Erickson’s long history with kinetic jewellery found a natural alignment in her work with plant forms; the movement of the work was not an abstract response to the movement of the body but rather a meaningful and life-enhancing meeting of nature and human nature. For such works she took the natural materials of this landscape – the metals, the iron ore, the gold, and the precious stones – ̶and made burgeoning, vegetative, plant-like forms with structures as light and delicate as so many native plants whose fragile, weightless, wiry lines appear to rest on air. Erickson’s pieces respond by touching the body intimately, moving naturally with the human form with the random gracefulness of nature.

In this more focused concentration on local flora and her mother’s paintings, few of the pieces are literal translations; they are instead evocations of the colour, shape, and habit of individual species, many of which are precious and endangered. In this body of work, she produced outstanding pieces of jewellery that fully honour her mother and her work while also realising the full potential of her own experience and technical expertise. It is as if Erickson is in a spacious place where there is room for the natural evolution of ideas and time for them to appear effortlessly.

Dorothy Erickson, Dampiera pendant, 2014, gold-plated sterling silver, lapis lazuli, steel cable, pendant 150 x 150 x 150mm. Wildflower Collection. Photo: Robert Firth.

Technically, Erickson was concerned to create a more physically embracing type of jewellery, making multi-piece creations that, again, respond to the body. This aspiration can be seen in the plants she is responding to such as the Hardenbergia, a cascading creeper that drapes itself over other plants and Leschenaultia’s opulent blue sprays that are luminous amongst the groundcover in the bush. In jewellery form they spill elegantly over a human shoulder or from a wrist. As such, these works speak not only of the wildflowers of this place but also evoke something of the human experience of being in the bush. They transcend mundane ideas of jewellery as a craft or as superficial decoration: they have a touching contemporary presence.

The Hesperia’s Voice Collection funded by a year-long grant from the Department of Local Government, Sport, and Cultural Industries in 2022 pays homage to the women who were among the first to make art as a profession in Western Australia, many of whom painted the unique flora of this international biodiversity hotspot. Most painted wildflowers and many were stars in their own time. As they have slipped from memory, Erickson’s research and writing about their careers has retrieved these ‘Angels in the Studio’ from oblivion. She has made jewellery that evokes their paintings, aspirations, and inspiration. From something so local as the plants and artists of this place, Dorothy has made objects of universal value. The series is as unique and exquisite as any historical jewellery ever owned by the rich and powerful or by the great connoisseurs of the past, and with its aesthetic lightness, feminine ethos, and hardy delicacy, it is uniquely hers.

Erickson’s work usually appears in series based on a dominant, animating idea. The Hesperia’s Voices collection continues her exploration of the lives of West Australian women artists who coincidentally mostly developed within the wildflower painting movement, the single most enduring tradition in the State’s history. Some, like Rica Erickson, became botanical artists while, for others, a door was opened to other opportunities. Some of Erickson’s jewellery here evokes the plants these wildflower painters illustrated while other works draw on the subjects chosen by these pioneering artists, such as May Creeth’s yachts on the Swan River or Loui Benham’s boats on Lago di Garda in Italy.

Dorthy Erickson, Loui’s Barca I – Hesperia’s Voice Collection, neckpiece, 2022, sterling silver, 18ct gold, stainless steel Milanese mesh cable, 250 x 250 x 20 mm. Photo Robert Frith.

Dorothy Erickson, Marie in Brittany I – Hesperia’s Voice Collection, 2023, sterling silver, 18ct gold, amethyst, stainless steel Milanese mesh cable, 280 x 240 x 14 mm. Photo Robert Frith.

Erickson has a thoroughly contemporary fluency in a design language that balances abstraction with literal meaning and gentle good humour with natural and artificial materials. First and foremost a designer, she is a translator of ideas into practical objects and freely exploits the technical expertise of others when she needs their assistance. What she creates, however, is always her own, strikingly unique, and perfectly coherent within the context of her preoccupations. There is a characteristic softness, a sense of gentleness and delicacy, in the way she balances these forces, melding geometry with metal and stone and process with vision. This is jewellery as art.

Dorothy Erickson has recently been named a WA State Cultural Treasure, and her latest book, Inspired by Light and Land: Designers and Makers in Western Australia 1970-21st Century, was recently awarded the Williams Lee Steere Book Prize.

About Philippa O’Brien

Philippa O’Brien, artist, curator, and art historian. Her most recent publication is NO STONE WITHOUT A NAME: Possession and Dispossession in Australia’s West, an illuminating and authoritative archive of West Australian colonial art.