The Russian crochet artist Katika explains how she discovered a craft that helped unravel her emotions.

I started crocheting when I was around seven or eight years old. After school, I went to free craft classes where we worked with clay, sewed traditional dolls, read folk tales and also learned to crochet. I made little bags, toys, and gifts for my friends. My mother also crocheted. She often made clothes for me and would unravel old pieces to remake them as I grew.

At the same time (7-8 years old), I became fascinated by drawing. I used to copy from children’s art books like “How to Draw Portraits” or “How to Draw Cats” and others like that. Since then, art and crochet have always gone hand in hand for me.

I attended a five-year art school for children, then went on to art college and eventually to the academy. But it was only in my fifth year, when I was 24 and pregnant, that I decided to try combining my fine art skills with crochet. I had already started oil painting, but it became too expensive, and I didn’t have a studio. Crochet felt accessible, physical and emotionally right. I tried knitting and sewing too, but they didn’t speak to me in the same way. Yarn and a hook became my tools. Over time, I developed a kind of personal philosophy around it.

My first pieces were ugly and funny-looking. I was embarrassed to show them. But I kept crocheting every day, trying to evolve the technique and connect it with the language of painting. In the beginning, it was difficult : people didn’t understand what it was. Was it art or was it craft? But now crochet is my language, my philosophy, my therapy and my way of thinking.

Around the same time I started my crochet art journey (in 2014), I also created an Instagram account. Back then, it felt a bit shameful for an artist to use Instagram (it was mostly a place for posting vacation feet pics and food ) but I just needed someone to share with. Very soon, a gallery owner from Tokyo reached out to me, and I started preparing for my first solo show.

As things developed, I began exhibiting more and more (mostly outside of Russia), though I did have some shows here too (mostly with places where I had previously shown traditional paintings).

My first gallery contract was with The CAMP Gallery in Miami (though back then they were called DAM.)

But everything changed in 2022, when the war started. That was when I began showing more often in Moscow. Now, I’m at a stage where I really want to find “my” gallery, but I haven’t found the right one yet.

I think of the artist–gallery relationship a bit like a marriage : it’s a deeply meaningful bond that shapes many things. And if we follow that analogy… I’m a divorced artist actively dating again! Haha. I work on a project-by-project basis for now.

The terms are usually similar everywhere: a sales percentage, help with transport, organising shows, and so on. The more stable and established the gallery or institution, the more supportive and comfortable the conditions tend to be (but really slow).

The Winzavod Center for Contemporary Art is a Moscow institution located quite centrally (near Kurskaya metro station). It’s a large complex that includes about 11 galleries, exhibition spaces, cafés, shops, and more. The name comes from its past: it used to be a factory for wine and beer production.

I joined in 2022 by applying for the “Open Studios” program and was selected. After that, they offered me a studio space here (for a very small fee, thanks to a foundation that supports contemporary art). We have several spaces for artist studios: in total, about 20–25 artists work here. Some studios are very close to each other, and the artists vary: contemporary painters, graphic artists, ceramicists, performers, and those working in mixed media. Most of us are around the same age, between 28 and 35.

Honestly, I feel both proud to work here and constantly insecure; the competition and comparison are always present.

Right now, one of my works is part of a large group exhibition at Winzavod called “Limits of visibility”. There’s also a small, young gallery in Moscow called “Substance”, which currently represents a few of my works for sale (but that’s more of a friendly arrangement than anything formal.)

My daily routine is quite simple: I wake up at home (I live near the VDNKh metro station), get ready, and take the metro to my studio. I work here for 8–12 hours a day, then head home to sleep. I don’t really have any favourite places outside of home and the studio. But I truly love my little corner of the world. (If you’d like, I can send some photos.)

Each piece or series usually begins as a short note on my phone; it starts with an idea, an emotion, or a certain feeling. I spend some time reflecting on it, and then I begin to look for a visual form. Yes, I do make sketches, sometimes on my iPad and sometimes just on paper. Once the sketch is done and translated into colour, I start selecting and dyeing the yarn. And then comes the long, daily, meditative process of working with my hands and the hook.

Above all, I always think about the viewer: what might they receive from my works? For me, that’s a great responsibility as an artist. I try not to exhibit work that is too raw or unresolved. My first impulse is always to give something, not to take.

If there’s anything therapeutic for me, it’s not so much in being seen, but in the daily act of crocheting itself.

When the pieces are finally on view, I usually feel a mix of excitement and nervousness. There’s a sense of responsibility, and yes, a kind of reverent anxiety. If there’s anything therapeutic for me, it’s not so much in being seen, but in the daily act of crocheting itself. It’s like a prayer, or a meditation: something that quiets the mind.

And when I look at my practice as a whole (and I do try to reflect on myself and my work), I sometimes feel that I’m a kind of embodiment of Russian culture: suffering, intensity, struggle, deep thought, a bit of dark humor: all of it mixed with a kind of Third World naivety. Honest, raw, but often mediocre. Even the technique plays along with that narrative. But at the same time, I’m always striving toward something.

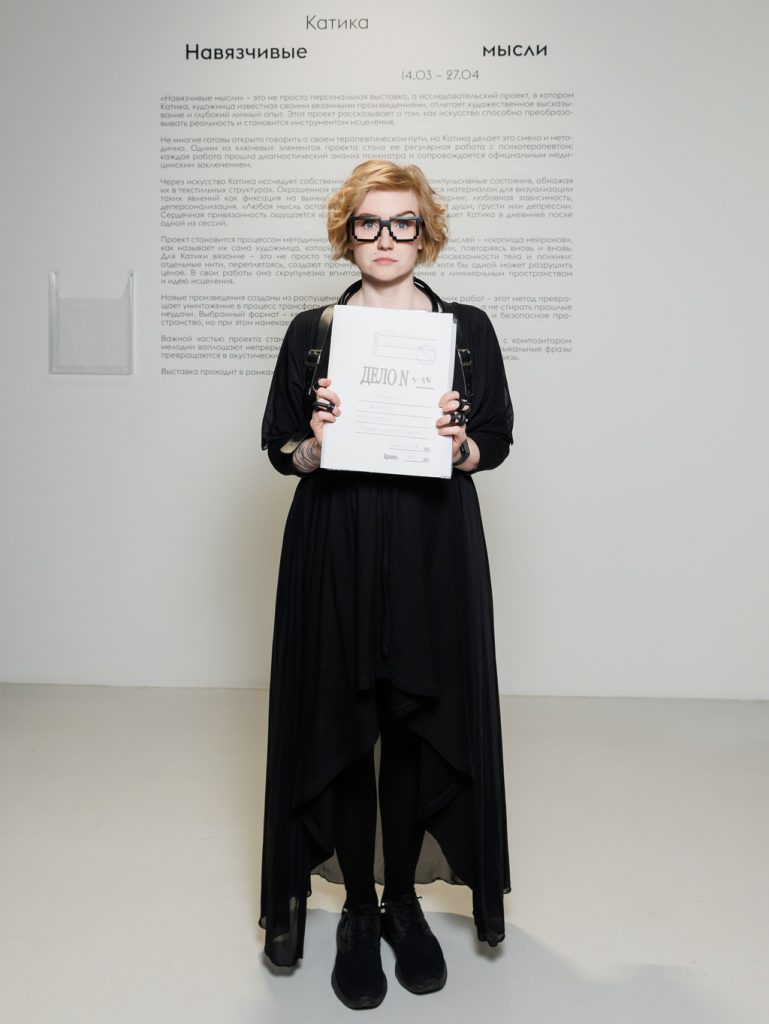

Obsessive Thoughts

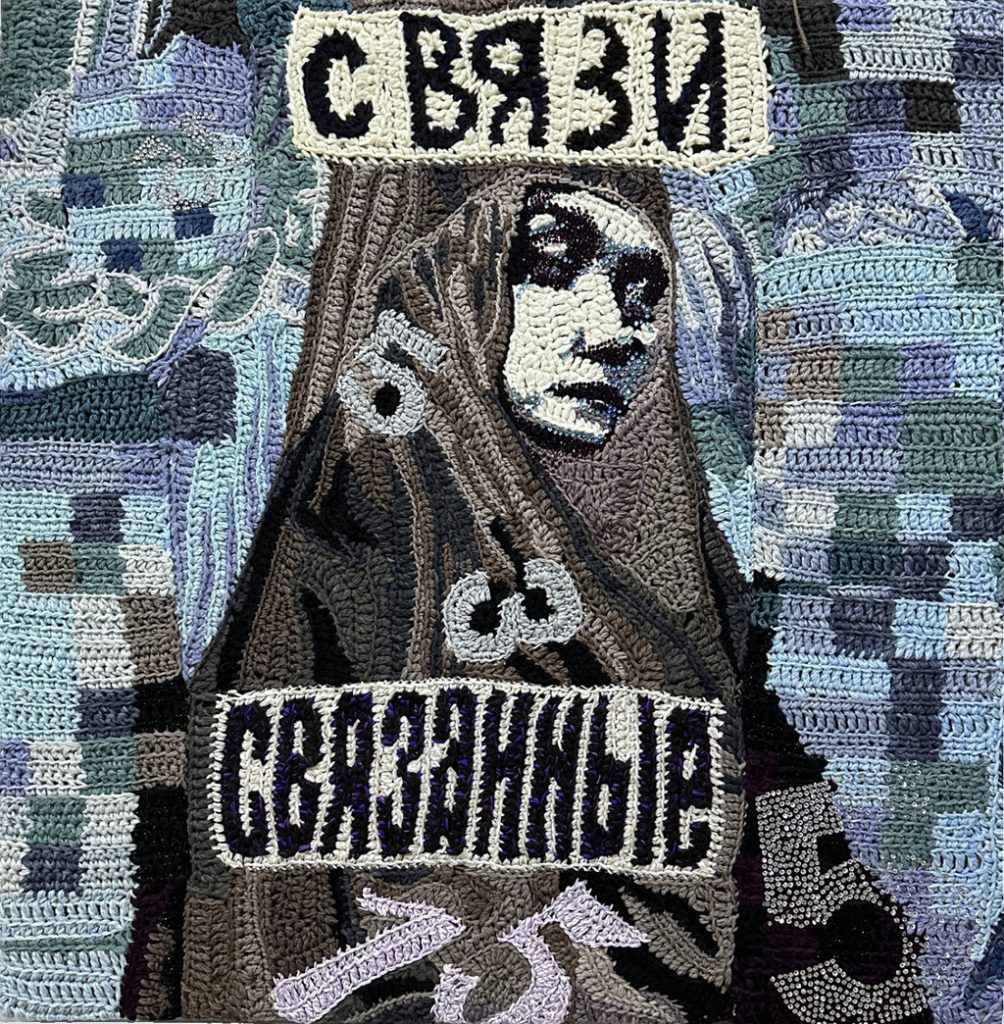

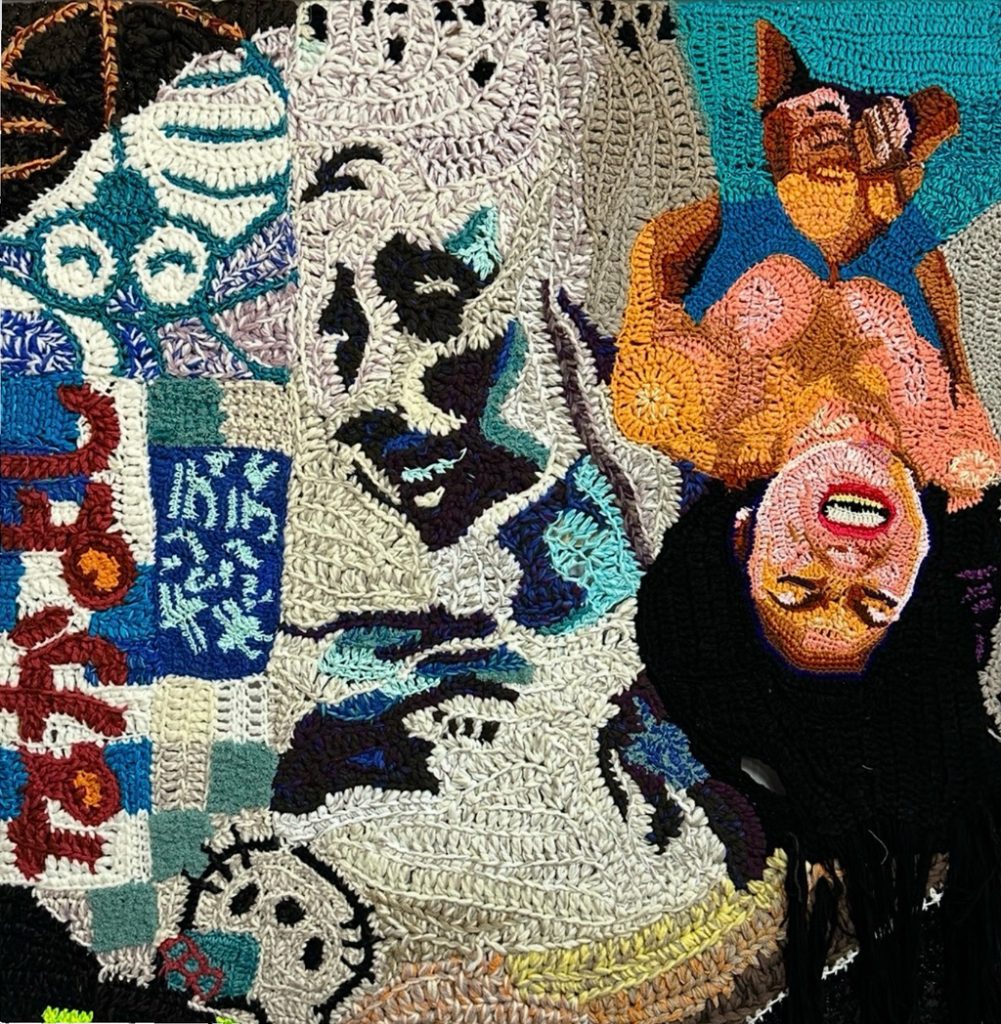

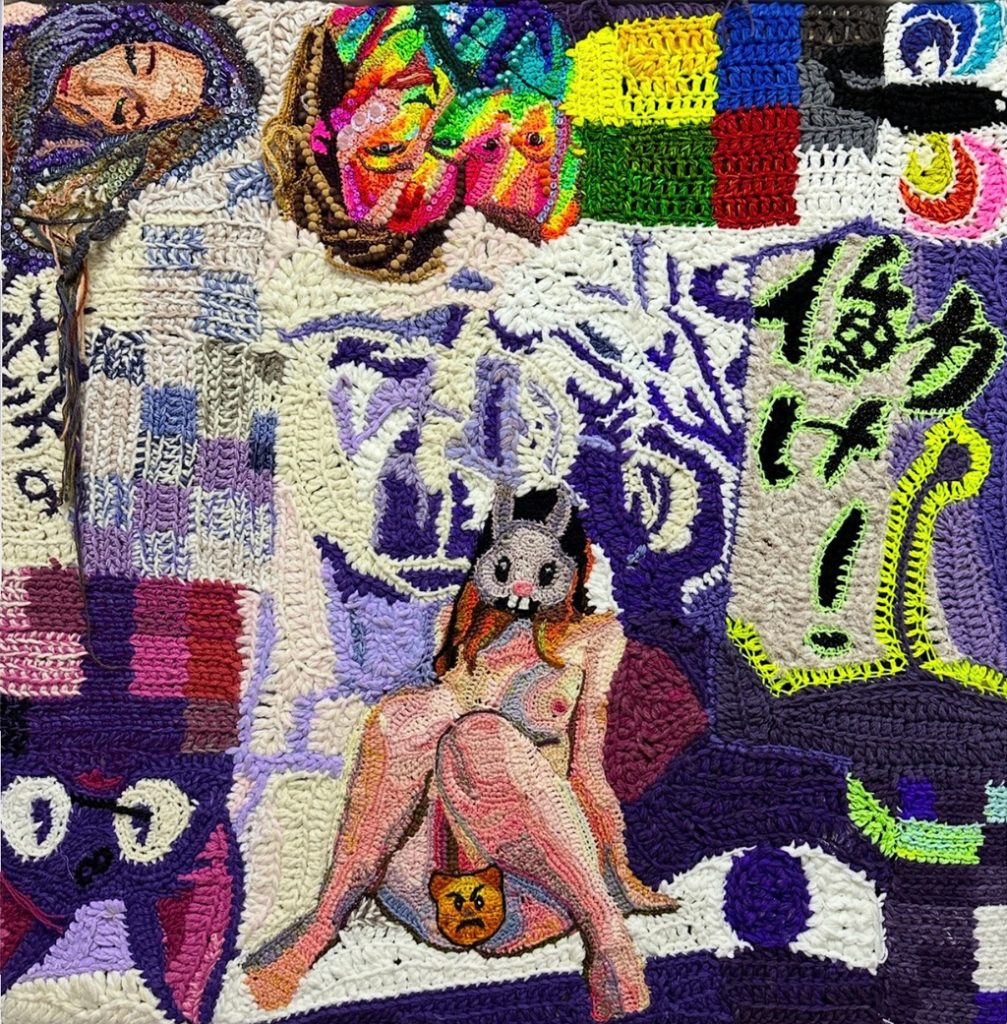

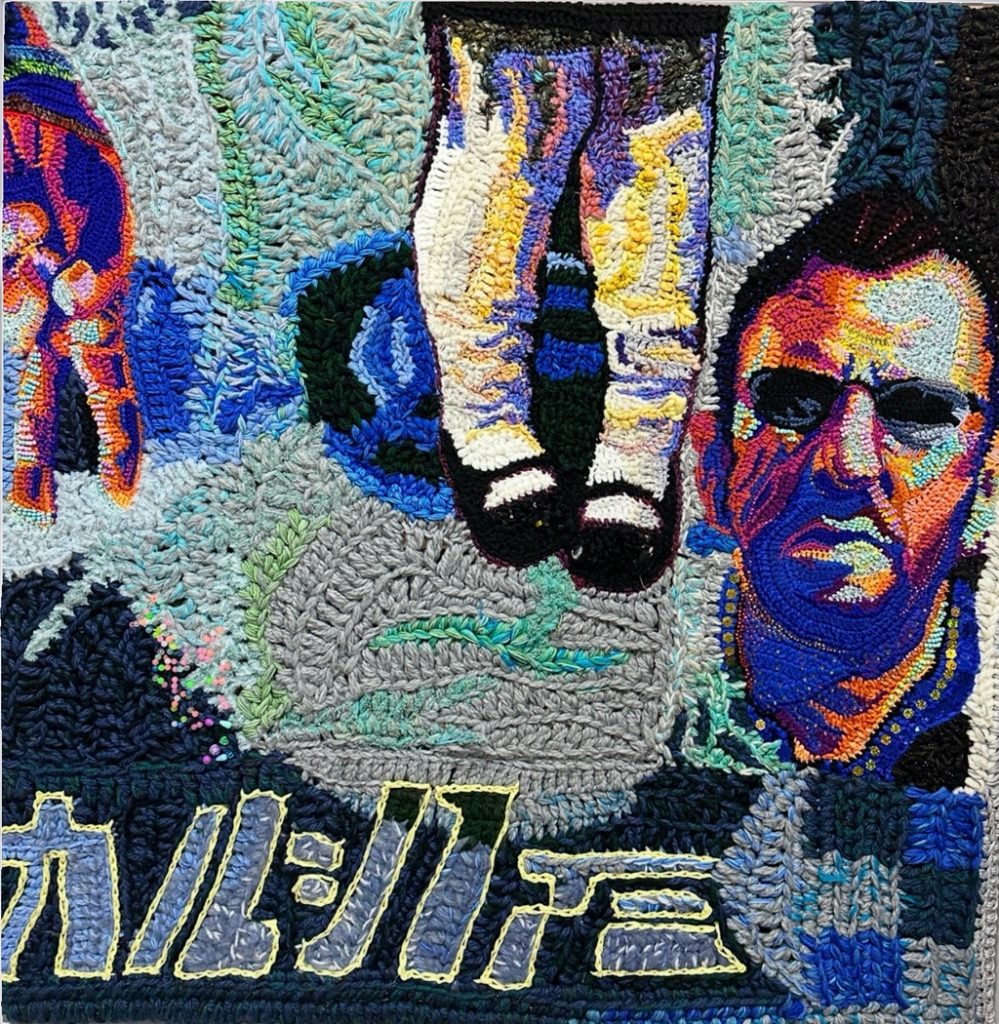

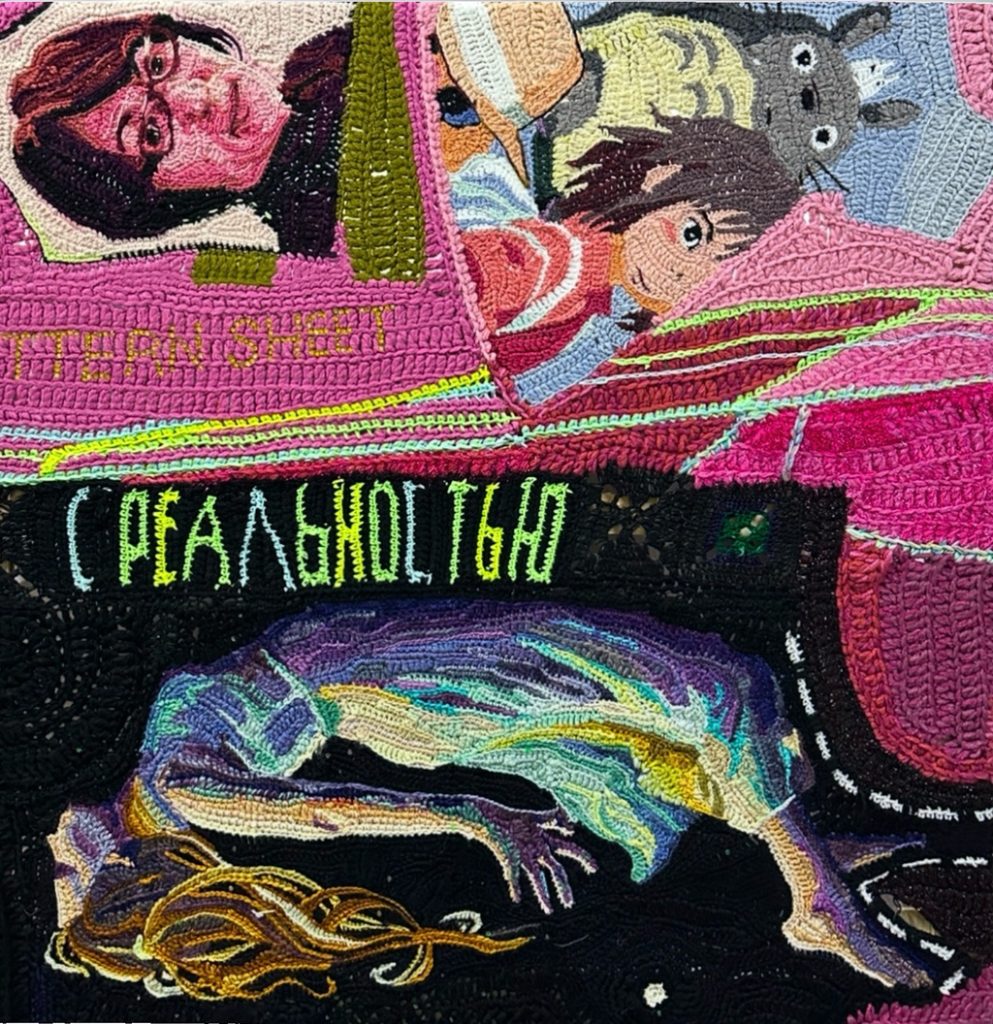

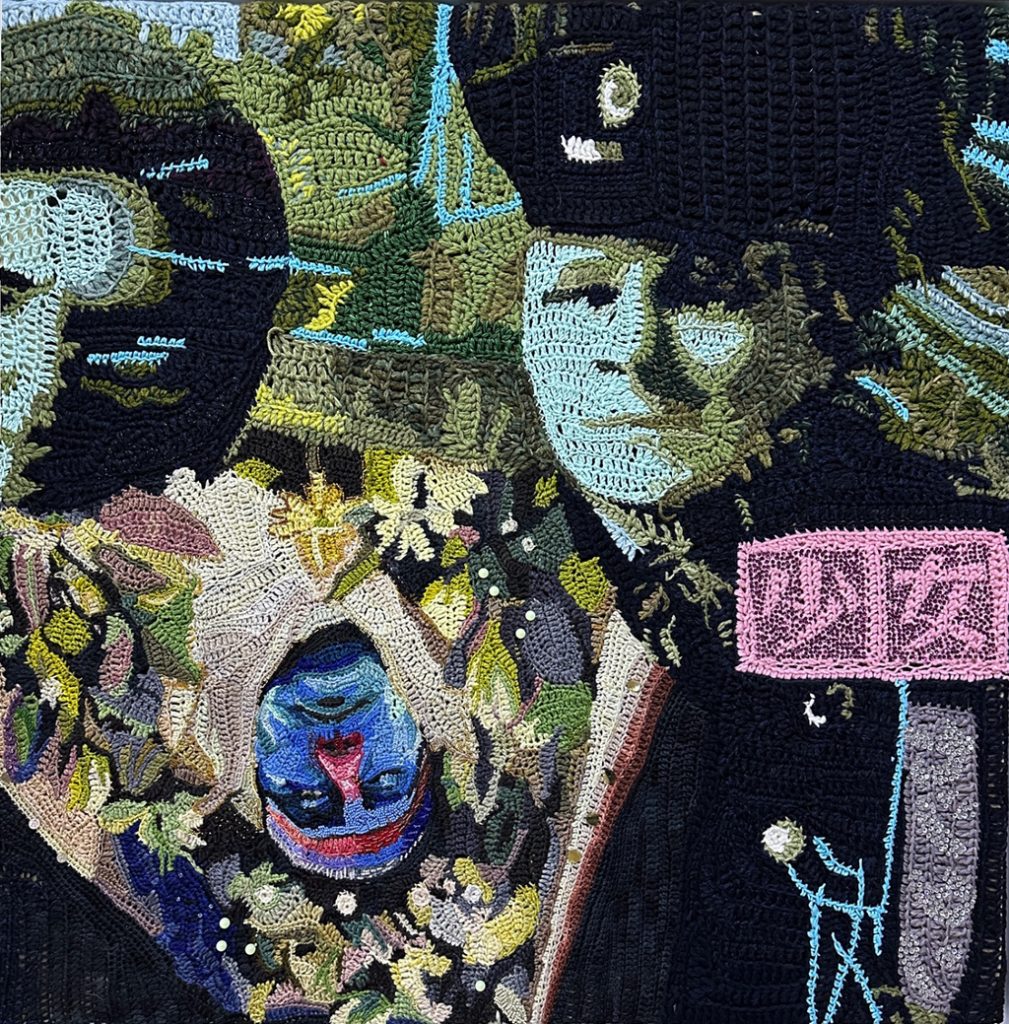

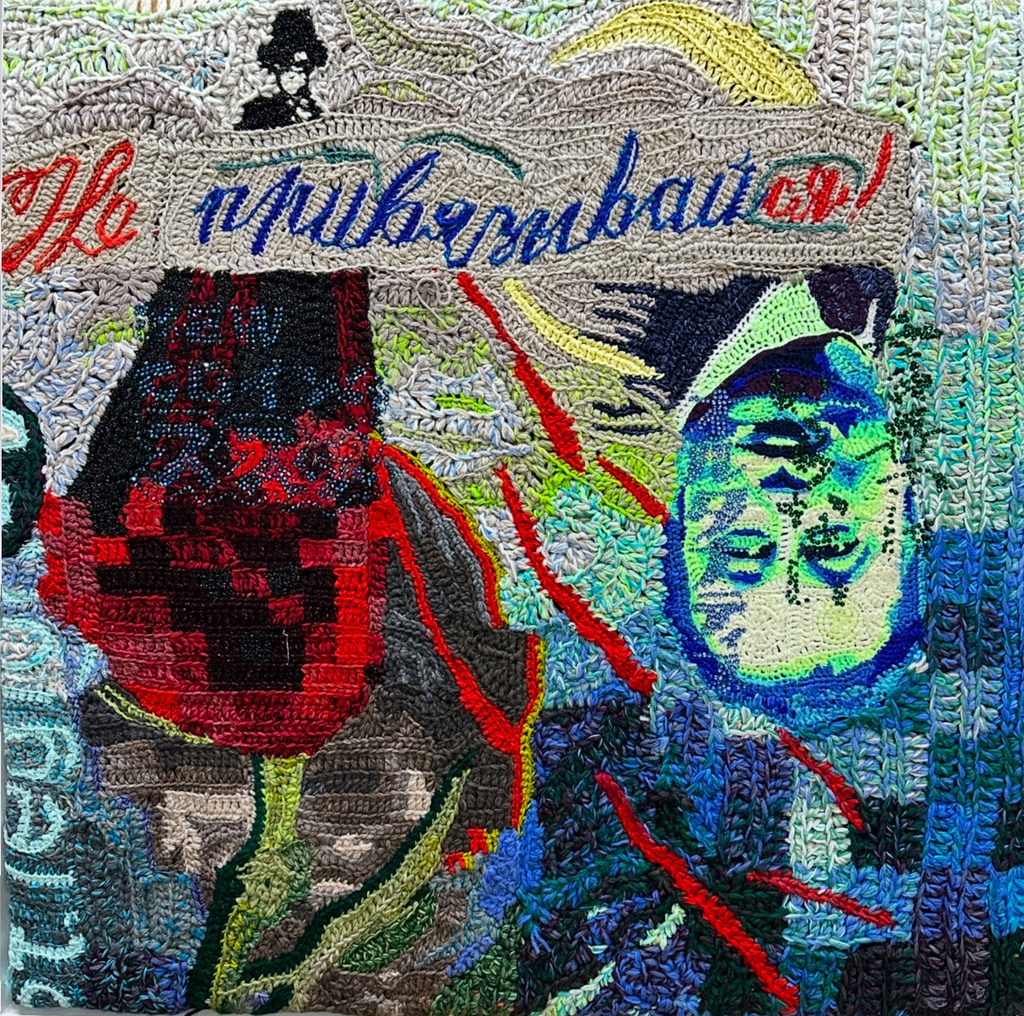

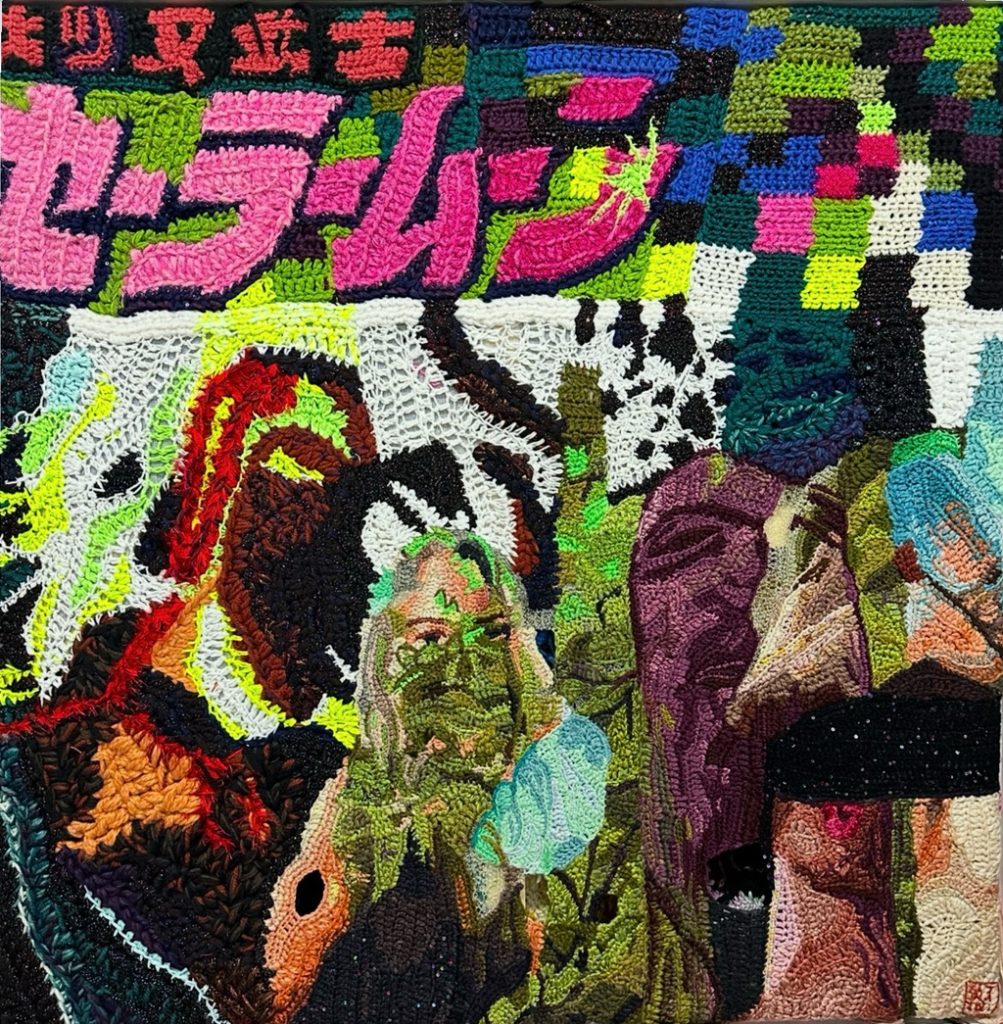

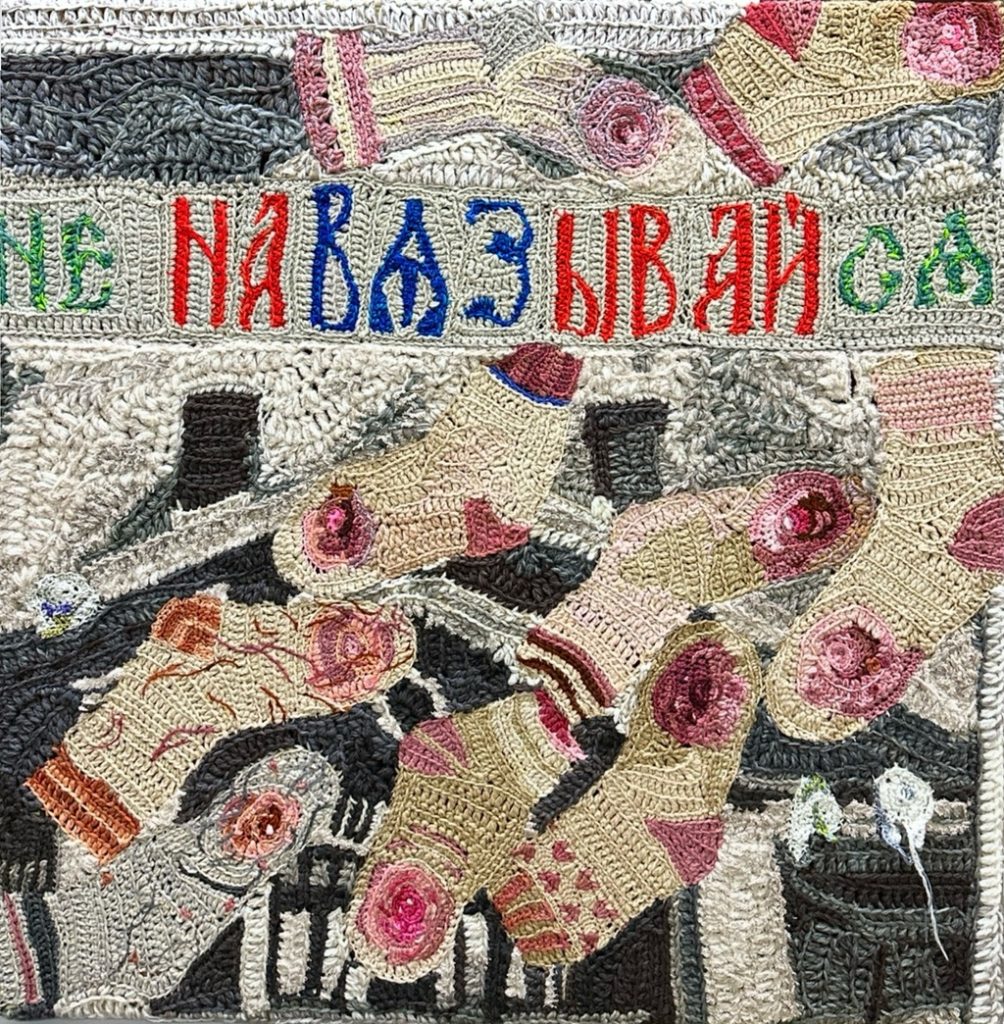

This project is a series of 15 crochet works created from fragments, leftovers, and previously unfinished or unrealised pieces made over the course of 11 years.

Each piece is accompanied by a folder containing a “psychiatric evaluation” not of myself, but of the artwork itself, imagined and written based on insights from sessions with my psychiatrist. Each work is also paired with a looping audio track, an obsessive melody from childhood, whether a fragment of a familiar song or a forgotten local tune. During the exhibition, these loops played consecutively.

This is not just crochet, it is an audio-visual-therapeutic archive, where each loop of yarn holds a memory, and each sound loop reflects an obsessive thought. The pieces have no titles; they are identified only by folder numbers: “Case 1”, “Case 2”, and so on. There is also a general folder for the project that contains an overview and background explanation.

Below are examples of the short texts that appear on the first pages of the folders (longer versions are available upon request):

Case 1

This piece reflects a deep inner conflict connected to attachment and its destructive potential. The central theme is a struggle with love addiction, whether emotional dependence or a need to dominate.

The story shows how rejection can lead to aggression that turns inward, where the aggressor becomes the victim.

There is also an ironic reference to both Tuxedo Mask and Elon Musk.

The stitched text reads: “Don’t get attached!”

Possible diagnosis: Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), self-harm tendencies.

Case 6

This piece explores the tension between masculine and feminine energies within the artist. She reveals her breasts a symbol of femininity which simultaneously evokes discomfort and conflict, emphasizing emotional dissonance with her own body.

The work also addresses impermanence and change, as the idealised feminine image fades into a photographic negative, symbolising instability and inevitable transformation. The artist finds emotional refuge in childhood memories, which serve as a source of safety. Japanese characters (the title of the anime Sailor Moon) appear in the piece.

Possible diagnosis: Identity disturbance, internal gender conflict, body dysmorphia.

Case 10

This piece explores the symbolic contrasts between personal identity and the harshness of the art world.

Nipples act as unique “identity prints,” like fingerprints, symbolising either strength or vulnerability. Socks represent warmth and childhood comfort, contrasted with the cold, competitive realm of contemporary art.

It reflects a clash of worlds: the aggressive, toxic adult sphere versus the gentle, nurturing world of the child.

In the background is the Winzavod Contemporary Art Center, where the artist’s studio is located. The text reads: “Don’t impose yourself!”

Possible diagnosis: Neurotic disorder caused by a toxic environment, emotional burnout.

Other Works

About Katika

Visit katika-art.com and follow@katikaart