Annette Peterson writes about five textile artists who weave a sensitive exhibition from text and thread.

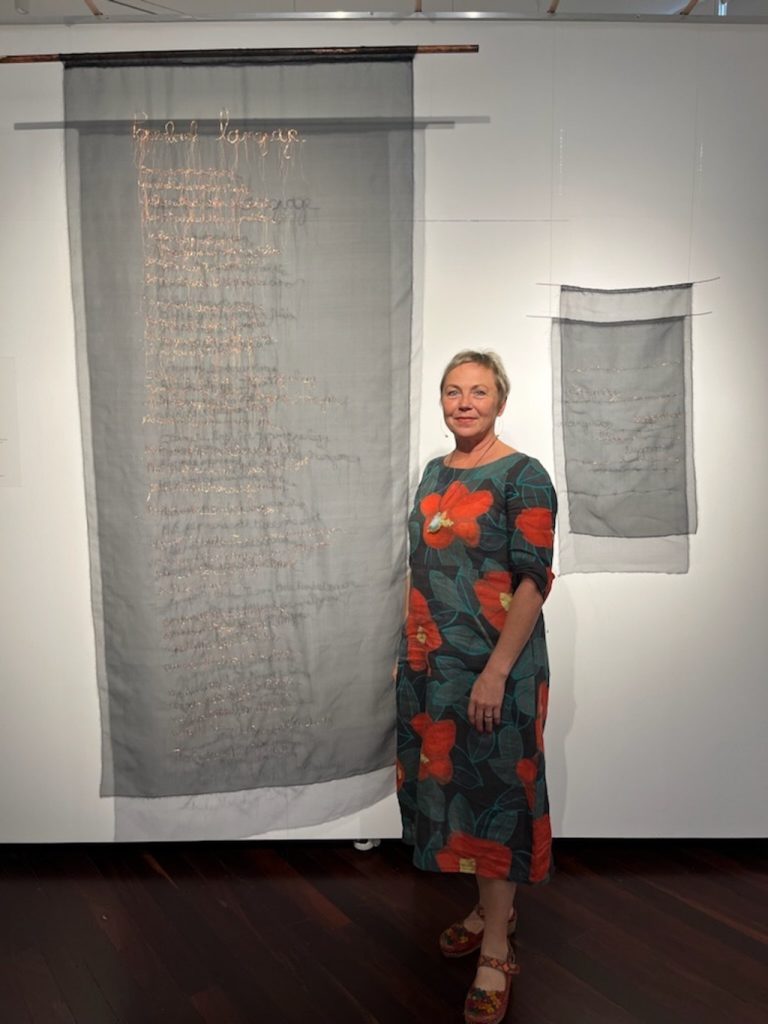

In LAND (WORD) JOURNEY, an exhibition exploring the relationship between words and country, in the form of visual poetry, Tineke der Eecken’s “Paperbark Language” spans the gallery. Two metres of silk adorned with flowing strands of quilting yarn form copper letters. The layers of the letters make it indecipherable, reflecting the forbidden paperbark language of the Indigenous First Nations people. This process of exploring the layers of presentation, materials, and, ultimately, meaning sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition.

Van der Eecken is an artist, author, and poet who has published works in Australia, the UK, the US, New Zealand, and her home country of Belgium. As an artist, she has widely exhibited her work, including at the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. She has toured across Western Australia with Art on the Move and collaborated with SymbioticA at the University of Western Australia (UWA), exploring resin casts of animal circulatory systems.

Another compelling work by Van der Eecken is “On Language” (duration: 3 min, 12 sec), a poem read by the artist in Flemish, French and English. In a darkened room with no lighting, I had to attune my senses to her voice to comprehend the meaning as the words flowed. I found a connection with Van der Eecken as she spoke about her homeland. “No language, no words in English,” her voice declared, “The wind laughs at the shimmering waters…”

Her voice resonated deeply with my own memories and experiences. Initially, I thought the piece resonated with my homeland, which made me feel a sense of connection. But as I heard other languages foreign to me, I began to feel isolated, unmoored. I imagined a world where I understood no one, where the language around me held no meaning. I started to grasp what it might feel like for a community to lose their language and be surrounded by signs and systems they do not understand.

This experience stayed with me long after leaving the gallery. I had thought of myself as compassionate about the subject, but I realised I had not understood the weight of cultural loss. The work compelled me to reflect on language, belonging, and cultural erasure. Without it, I may not have considered these ideas quite so deeply. It made me conscious of a silence I had not noticed before. Van der Eecken’s work is powerful, quiet and effective.

Her other works in the exhibition include jewellery, a sculpture made from copper, wood, and silver, and further silk works embedded with copper lettering.

First Nations artist Sharyn Egan’s “The Glue That Binds Us“ is a balga tree resin painting that forms a vivid, abstract landscape in shades of red. The resin creates thick, dark regions that are almost black, contrasted with translucent red areas. To me, it suggests blood and the trauma held in bloodlines while also referencing the strength that binds us to ancestry. Egan captures a powerful sense of inherited pain and memory.

In “The Land Remembers“, Egan uses woven paper stained with ochre, watercolour and balga resin. Atop the intertwined foundation sit bones and quandong seeds. It is set up like a board game and evokes an element of play. The bones suggest memories of the past, epitomising past life, while the quandong seed that produces vitamin-rich fruit represents potential renewal and new life.

Egan, a child of the stolen generation, has artwork in the National Museum of Australia, the Art Gallery of Western Australia, and the Berndt Museum of Anthropology. She has also had her art represented at the Perth International Art Festival. Her work honours her connection to Nyoongar Boodja and calls on us to reflect on our responsibilities to land and country.

Carol Igglesden is known for her asemic works and her use of written graffiti, or ‘Calligraffitti,’ as she calls it. As an Associate Lecturer at Curtin University, she approaches the writing on the wall as if the walls themselves could speak. Her language is nonsensical yet magical, featuring words such as “sector” and “midnight,” which appear and then fade into the indecipherable. Even though calligraphy is an esteemed art form in its own right, by shedding the literal meanings of the words, Igglesden brings them to life as symbols.

Her writings sprawl across canvas and paper among other materials in layered and considered ways. The abundance of her work hung salon-style, appears to deter the viewer from seeking meaning in the words of her works. Had there been less work, then the impact would have been lost. By abstracting the symbols, she strips language of meaning, much like the Russian Futurists did in the 1920s. Her mark-making becomes a visual language more about rhythm, gesture, and energy than translation, and disrupts typical ways of viewing.

Natalie Damjanovich-Napoleon with some of her collage works, behind her and in front. Paper, Book Ephemera. Photo Josh Wells Photography.

Natalie Damjanovich-Napoleon has gained acclaim as a singer-songwriter and poet in both Australia and the USA. Her spoken word piece “More Flies Than Stars”, was presented at the opening and captures the essence of a rural Australian perspective. And yet, based on the experiences of her family members who immigrated to Australia from Yugoslav, she has created a series of collages using words and images that cross-reference between Yugoslavian and Australian cultural perspectives. Damjanovich-Napoleon has demonstrated this in “Slav Ship: Shouted Partizanka”, which is about Yugoslavs (as they were known at the time) leaving Australia following the 1938 race riots, which drove them out of Kalgoorlie, WA, to return to Yugoslavia on the Partizanka and help rebuild the country post WWII.

- Lakshmi Kanchi Metamorphosis & The Sikworm

- Lakshmi Kanchi with Metamorphosis & The Sikworm

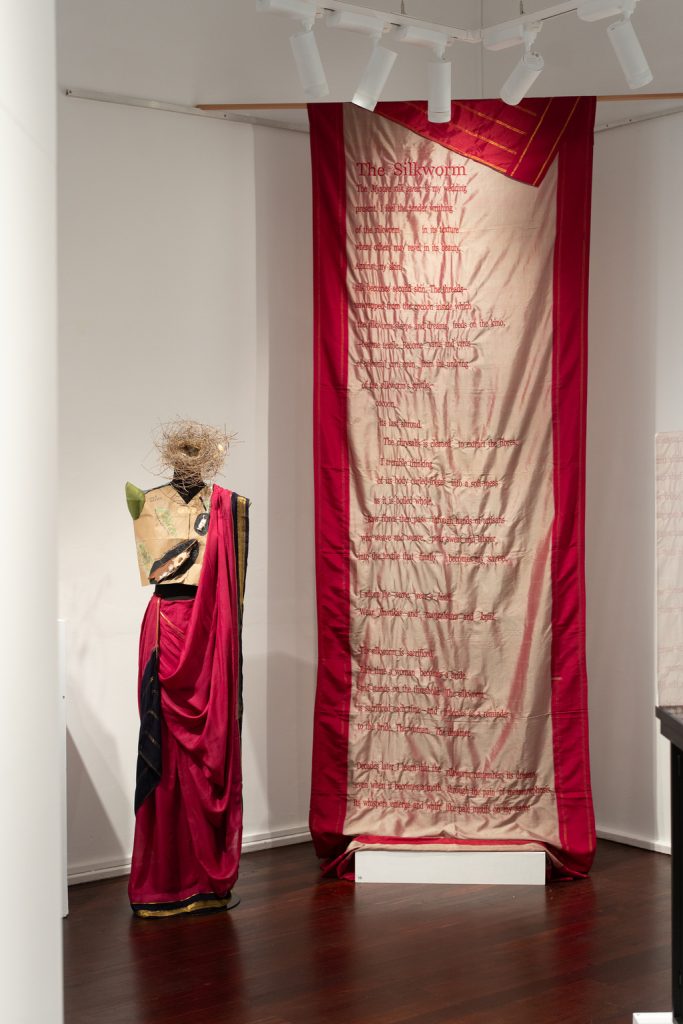

Indian/Australian poet and artist Lakshmi Kanchi’s interwoven works, “The Silkworm, Metamorphosis, and Requiem for a Moth”, layer the Indian bridal ceremony with the lifecycle of the silkworm. These works explore themes of migration, tradition, and metamorphosis, both physical and spiritual. Bright magenta silk cascades over three metres to the ground, representative of the bridal saree. “The Silkworm” is a poem which has been hand-embroidered with resha thread. It describes the silkworm’s sacrifice, spinning itself into silk for a wedding ceremony, a metaphor for a woman’s transition into her new home and culture. The embroidered words physically pull the fabric inward, almost like an hourglass, recalling the female form.

In “Metamorphosis”, Kanchi incorporates her great- grandmother’s wedding saree in the same bright magenta. She has paired it with a paper vest and a nest of silkworm cocoons. “Requiem for a Moth” is a delicate interactive piece, containing a poem and a nestled silkworm moth, signifying the full life cycle.

Additionally, “Indigo” by Kanchi explores the colonisation and ecological devastation of the now-defunct Neel farming practice in India, which was previously used to harvest indigo dye. Her multi-faceted artworks and related poem “Dreams of Neel” are a reclamation of colour, history, and agency.

Anthropologist Tim Ingold, in Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (2011), argues that artists create “lines of becoming” pathways that shape the texture of the world. The artists in LAND (WORD) JOURNEY do just that. Through silk, copper, resin, ink, language, and silence, they construct delicate and layered lines that trace identity, memory, and transformation.

Through their unique cultural lens representing the marginalised or overlooked, the artists navigate their associations with words and country. The abundance of works in a compact space, each possessing multiple layers and profound ideas, might lead one to speculate whether more spatial allocation would have enhanced the experience. However, it is more likely that the artists have intentionally interwoven their narratives throughout the exhibition to deepen the texture of the world they present. This curation method allows the viewer time to explore the layers of design, materiality, and meaning of the artworks individually, while also discovering quiet connections with the other works.

LAND (WORD) JOURNEY Tineke Van der Eecken, Natalie Damjanovich-Napoleon, Sharyn Egan, Carol Igglesden and Lakshmi Kanchi, 11 May – 13 July Midland Junction Art Centre, Western Australia.

Reference

Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge, and Description. Routledge, p 178.

Annette Peterson holds a Master’s degree in Applied Design and Art. She is an emerging visual artist and writer who writes for local art publications.