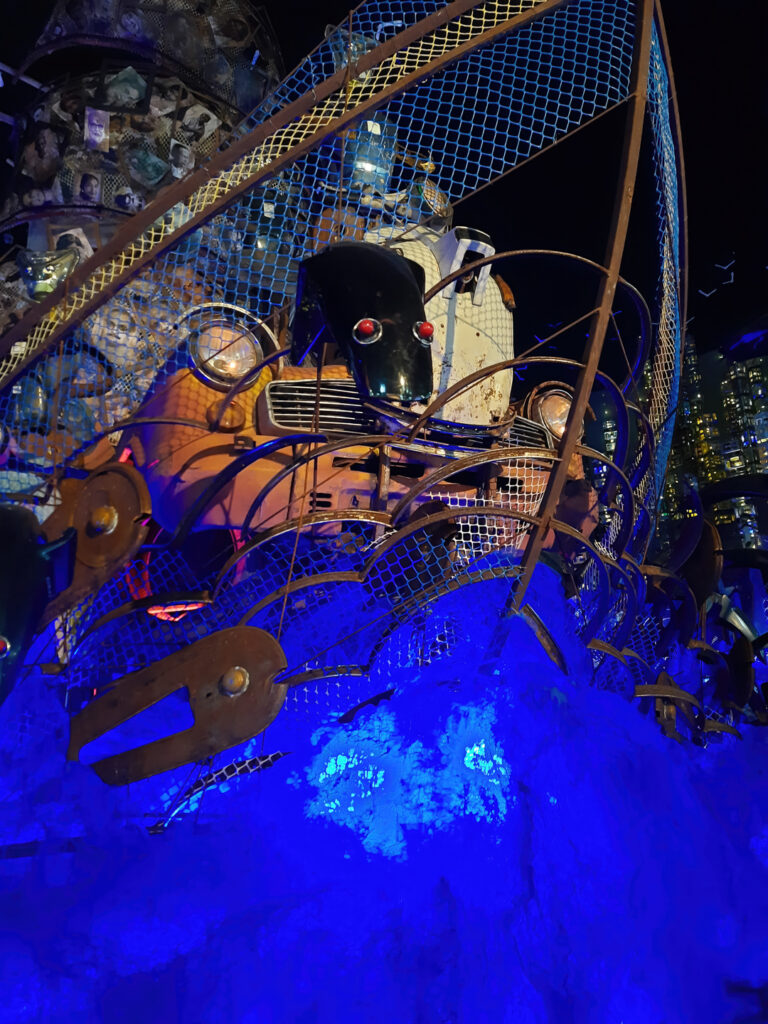

Inside the Durga Puja pandal of Tridhara Sammilani club, Kolkata, 2015. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

Aishani Gupta from the MAP Academy reports on one of the world’s great artistic events, held on the streets of Kolkata, for the eyes of the gods.

As the autumnal shiuli flowers spread their fragrance in eastern India, Hindu Bengalis prepare to welcome the goddess Durga, a powerful deity epitomising Shakti, the divine feminine. On her annual earthly visit, she will be admired and worshipped as the ten-armed Mahishasuramardini — “slayer of the buffalo-demon”— by hundreds of thousands of people pouring into the streets. Instead of the stone, brick and mortar of temples, however, she will be housed within temporary pavilions that take myriad forms, showcasing dizzying sculptures and installations that go far beyond sacred iconography — from giant birds and film stars to foreign monuments and technological landscapes. Shrouded in chants and heavy clouds of incense, she will be surrounded by dancers and drummers, food carts and game stalls, as well as lurid advertisement hoardings. Today these pavilions, or pandals, are at the spiritual, artistic and commercial heart of the annual Durga Puja, or pujo, celebrations, the most extravagant Bengali event of the year.

Traditional ‘Dhunuchi’ dance at a Durga Puja pandal, using earthenware filled with incense, October 2014; Video by Sandeep S. Rodrigues

In a city like Kolkata, hundreds of local clubs and committees start preparing their respective pandals weeks or months before pujo. Bylanes, playgrounds and other civic spaces begin to sprout often expansive and imposing structures of bamboo, metal, tarpaulin and cloth — until, during the five-day festivities, the city is a maze of walk-through installations that occupy thoroughfares and neighbourhood squares. Designed along the plan of a typical Indian temple, the pandal contains a stage at one end to hold the idols and host rituals — thus representing the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) — with the rest of the enclosed space variously serving the functions of communal worship, revelry, and dance and theatrical performances, much like the temple’s mandapa or gathering hall. The outward similarities to the traditional temple, however, end here.

Replacing the intricately carved toranas or sacred gateways are lightweight arches and vinyl screens saturated with corporate logos — from jewellery and cement brands to sweet-shop chains — the landscape of temples is also a commercial canvas. Every year, more than 10,000 pujos are organised annually in the state of West Bengal, and corporate spending in Kolkata alone is between 650–950 crores INR (80-120 million USD) per year. Pandals vie with each other for footfall and for corporate-sponsored awards — and so innovation, artistry, novelty, scale and memorability come to the fore.

- Building a pandal on a thoroughfare, Bhowanipore, Kolkata, 2024. Photograph by Aishani Gupta.

- Pujo light decor Hindustan Park Sarbojanin club, Kolkata, 2024. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

Today, themed or topical pandals take forms as diverse as Rajasthan’s fortresses, Mughal monuments, European architectural wonders, and even international war zones. They also ride the waves of contemporary issues like the Covid-19 pandemic, climate change and women’s empowerment. Beyond wood, bamboo and jute, pandal designers now use materials ranging from papier mache, metal alloys, utensils and found objects, to seeds, nylon mesh and automobile parts. Preparations for some of the bigger pandals often begin a year in advance and many occupations like idol-making, costume-design as well as preparing music and performances for pujo have now become year-round activities, generating income for hundreds of thousands of Bengalis.

- Pandal designed as Rome’s Trevi Fountain, Santosh Mitra Square club, Kolkata, 2013. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

- Pandal made of mosquito nets, thermocol and jute, Haridevpur 41 Pally club, Kolkata, 2015. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

- Old car parts used in the decor of pandal, Suruchi Sangha club, Kolkata 2024. Photograph by Aishani Gupta.

- Children’s drawings used as pandal decor, SB Park Thakurpukur club, Kolkata 2024. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

Meanwhile, the making and representations of the goddess and her cosmic children, Lakshmi, Saraswati, Ganesha and Kartik, have changed little over centuries; the elongated fish-shaped eyes and graceful countenance of today’s sarbajanin (community) idols follow those that featured in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sabeki (traditional) pujas privately hosted in the sprawling mansions of Bengal’s landed elites. While skilled and unskilled workers raise the structures and installations of the pandal, the icons that will occupy its sacred centre are created by Bengal’s premier patuas (idol makers), some of whom are descendants of nineteenth-century Kalighat patachitra artists. The clay form is made over a core of straw, the face of the goddess expertly sculpted by a specialised mritishilpi, or clay craftsman, who uses a reusable plaster mould unique to his style. Once dried, the clay idols are coated with a base paint of chalk and tamarind seed gum, before being painted with iconographically significant colours — the yellow typically used for her skin, for instance, connotes Durga’s radiant golden hue as described in the ancient Puranic scriptures. On the auspicious new-moon day of Mahalaya, which marks the beginning of pujo festivities, the idols are sacralised with the painting on of their eyes. This final step in their making is entrusted only to the most experienced artisans, whose hands will convert the material artefact and art object into a sacred and living icon.

- Making traditional idols of straw and clay at Kumortuli (potters’ neighbourhood) in Kolkata, 2017. Photograph by Ankur P. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

- Expert artisan painting the eyes of the Goddess on Mahalaya, 2022. Photograph by Ankur. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Some themed pandals nevertheless replace the conventional iconography of the goddess with faces of national heroes, movie stars, politicians and other famous personalities; and her customary silk, brocade or sola adornments with experimental materials like jute, paper, matchsticks and even broken glass. With the creative aspirations for pujo pandals taking ever greater flight in the last few decades, there has been an impetus among organising committees to treat them as public art in earnest — sometimes revealing tensions, particularly where the icons themselves are concerned. Since the 1980s, many pujos have commissioned renowned contemporary artists to design the idols. Some, like the Surrealist Ganesh Pyne, have refused, citing the incompatibility of Modernist aesthetics with the artistic vocabulary required for religious worship. For a renowned Kolkata pujo in 1990, the artist-anthropologist Meera Mukherjee rendered Durga in an Indigenous idiom inspired by the communities she had been living and working with and draped the deity in the sari of the local Santhal people. Not only have these deviations from Brahmanical narratives received backlash from spectators, but they have also set contemporary artists on a collision course with the hereditary patuas who consider themselves to be true practitioners of the form. Some pujo organisers have attempted to strike a balance by arranging for small traditional icons for devotional purposes, whilst simultaneously installing much larger “art idols” for public appreciation.

- Modern ‘art’ idol surrounded by traditional Kalighat patachitra paintings, Shibmandir club, Kolkata, 2023. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

- Idols conceptualised as Purulia ‘Chhau’ dancers, Ajeya Sanghati club, Kolkata, 2015. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

- Idols conceptualised as ancient Egyptian Gods, Kalighat BBTA club, Kolkata, 2024. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

- ‘Sabeki’ idol at Baghbazar Sarbojanin club, Kolkata, 2016. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

On the sixth day after Mahalaya, the goddess is revealed to public view amidst ritual and ceremony. As in diverse religious traditions across South Asia, devotees seek blessings from the deity through the act of beholding her, while being “seen” by her. From the crucial painting of the idol’s eyes and the darshan or sacred “viewing”, to the carnivalesque galleries this occurs in, as well as the images and logos of its contemporary patrons and sponsors — Durga Puja is solidly premised on the interactive act of spectatorship. In the crowded and frenetic spaces of pandals, however, it is impossible for the devotee or visitor to spend more than a few moments contemplating the divine, and darshan occurs in a constant state of motion. In these mid-street galleries, there is no white space and hushed silence, no frames and plinths. Exhibits both sacred and worldly are packed together, immersive, jostling for “views” and impact. Masses of people, families and entire neighbourhoods, are hustled through pandals by civic volunteers and guards as they go ‘pandal-hopping’, capturing the ornate yet impermanent sights with their mobile phone cameras.

- ‘Seeing’ the Goddess, Behala Friends Club, Kolkata, 2024. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

- ‘Pandal-hopping’ crowds at Baghbazar Sarbojanin club Kolkata, 2014. Photograph by Biswarup Ganguly. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

- Pandal as gallery, Behala Mukul Sangha club, Kolkata, 2023. Photograph by Arka Dyuti Palit.

- Ritual aarti at a Durga Puja pandal, Kolkata, 2021. Photograph by Archi Banerjee.

On the tenth day, it is time for the goddess to return to her cosmic realm: in Kolkata, idols are immersed in the Hooghly River, a tributary of the holy Ganga. With song, dance and a symbolic play of vermilion, she is bid farewell. Amid jubilant cries of “Aasche bochhor aabar hobey!” (“Next year, once again!”), the deities are taken out on a procession to the river, leaving a lone flickering lamp in the pandal. Over the next few weeks, workmen carefully dismantle the structure: the banality of everyday life returns to public spaces, which have hosted both the sacred and the spectacular. Other than the odd pit where a bamboo pole was dug into the ground or a hoarding languishing in the dirt, the city’s streets, squares and fairgrounds will carry no memory of the event. Yet those who witnessed it will carry it — along with the anticipation and knowledge that it will return in forms both reliable and surprising year after year.

- Sindoor Khela, Durga Puja celebrations in Assam, 2020. Photograph by Diganta Talukdar. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

- Immersion of the idol in the Yamuna river at Delhi, 2012. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

About Aishani Gupta

Aishani (she/her) holds a PhD in History from SUNY Stony Brook, where she researched South Asian religions, art and architecture, the British Empire, and colonial and postcolonial urban spaces. She is the recipient of Charles Wallace India Trust Grant and Royal Historical Society’s Research Support Award for her research in the UK. At the MAP Academy, she works as a copywriter on various research and outreach projects. She is based in Kolkata. Email: aishani.gupta@map-india.org.

Aishani (she/her) holds a PhD in History from SUNY Stony Brook, where she researched South Asian religions, art and architecture, the British Empire, and colonial and postcolonial urban spaces. She is the recipient of Charles Wallace India Trust Grant and Royal Historical Society’s Research Support Award for her research in the UK. At the MAP Academy, she works as a copywriter on various research and outreach projects. She is based in Kolkata. Email: aishani.gupta@map-india.org.

About the MAP Academy

The MAP Academy is an open-access resource focused on the art and cultural histories of South Asia.

Bibliography

1) Bhattacharya, Tithi. “Tracking the Goddess: Religion, Community, and Identity in the Durga Puja Ceremonies of Nineteenth-Century Calcutta.” Journal of Asian Studies 66, no. 4 (2007): 919-962. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20203237.

2) Chatterjee, Kumkum. “Goddess encounters: Mughals, Monsters and the Goddess in Bengal.” Modern Asian Studies 47, no. 5 (2013): 1435-1487. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24494217.

3) Das, Abhinandan. “Deciphering the Themes of Durga Icons in the light of the COVID-19 Pandemic in West Bengal, India.” Indian Journal of Spatial Science 13, no. 2 (2022): 54-60.

4) De Matteis, Federico. “When Durga Strikes: The Affective Space of Kolkata’s Holy Festival.” Ambiances, Varia (2018): 1-24. http://journals.openedition.org/ambiances/1467.

5) Fell McDermott, Rachel. Revelry, Rivalry, and Longing for the Goddesses of Bengal: The Fortunes of Hindu Festivals. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

6) Ghosal, Chandikaprosad. “Kolkata’s Changing Puja Ethos.” Economic and Political Weekly 41, no. 46 (2006): 4727-4729. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4418911.

7) Ghosh, Anjan. “Spaces of Recognition: Puja and Power in Contemporary Calcutta.” Journal of Southern African Studies 26, no. 2 (2000): 289-299. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2637495.

8) Guha-Thakurta, Tapati. In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata. Delhi: Primus Books, 2015.

9) Hussain, Preetha. “Durga Puja: The Sacred and Secular Aspects of Ritual & Performativity.” https://www.academia.edu/25702968/DURGA_PUJA_THE_SACRED_AND_SECULAR_ASPECTS_OF_RITUAL_and_PERFORMATIVITY.

10) MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art. “Mother Goddess.” Article. April 21, 2022. https://mapacademy.io/article/mother-goddess/.

11) MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art. “Patua.” Article. April 21, 2022. https://mapacademy.io/article/patua/.

12) MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art. “Kalighat Painting.” Article. April 21, 2022. https://mapacademy.io/article/kalighat-painting/.

13) MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art. “Chamunda.” Article. November 22, 2023. https://mapacademy.io/article/chamunda/.

14) Mitra, Anjan and Roy, Madhumita. “Durga Puja Festival (Public Event) and Puja Pandals (Public Space): A mutual engagement of Culture, Space and Time.” International Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity 12, no. 3 (2021): 191-208. http://www.irjmsh.com/abstractview/10799#

15) Niyogi, Subhro, and Mukherji, Udit Prasanna. “Not just fun, Kolkata’s Durga Puja is serious business worth Rs 15,000 crore.” The Times of India, October 10, 2024. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/not-just-fun-kolkatas-durga-puja-is-serious-business-worth-rs-15000-cr/articleshow/71549101.cms.

16) Sarma, Jyotirmoyee. “Puja Associations in West Bengal.” Journal of Asian Studies 28, no. 3 (1969): 579-594. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2943180.

17) Sircar, Jawhar. “Durga Pujas as Expressions of ‘Urban Folk Culture’.” The Times of India, October 23, 2011.