In response to the horror of war in her Ukrainian birthplace, Sveta Dorosheva immersed herself in the absurdist theatre of her Tel Aviv neighbourhood.

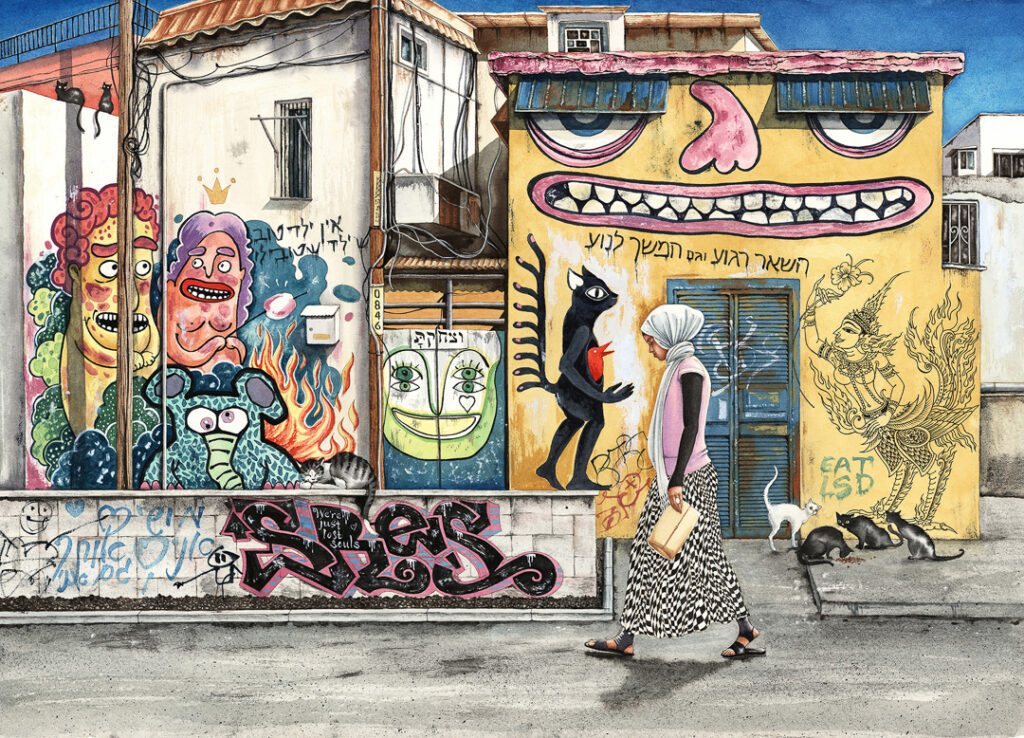

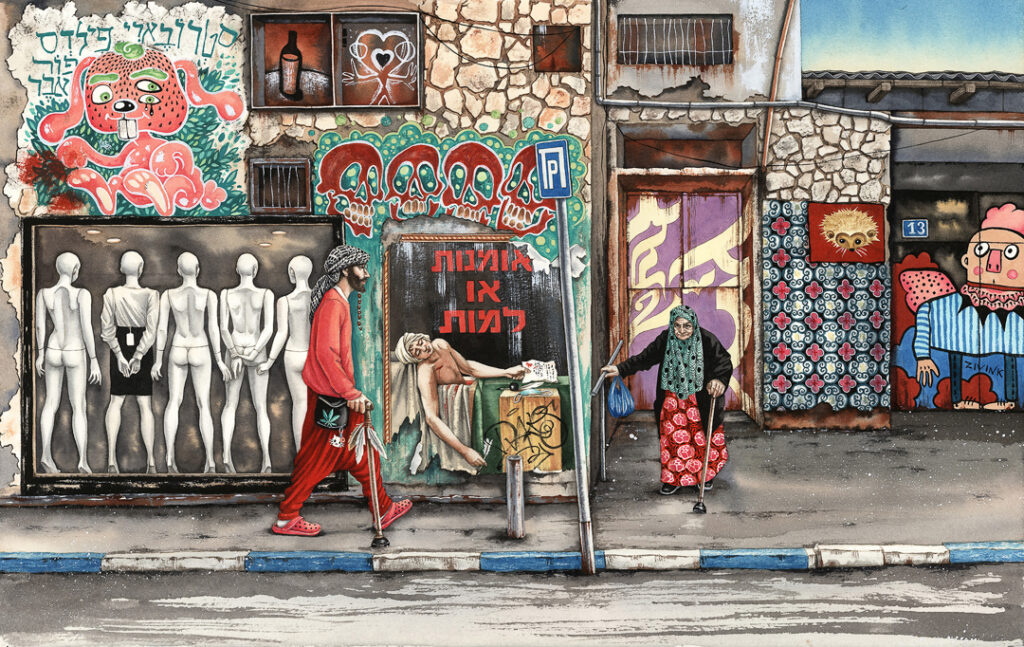

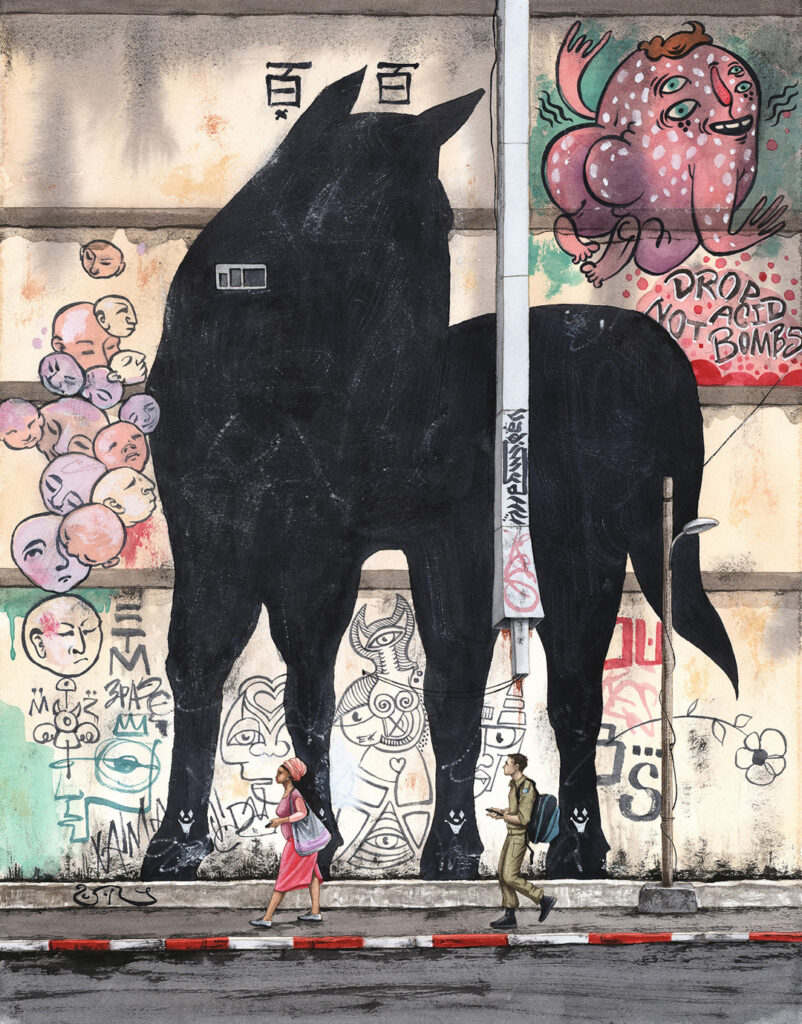

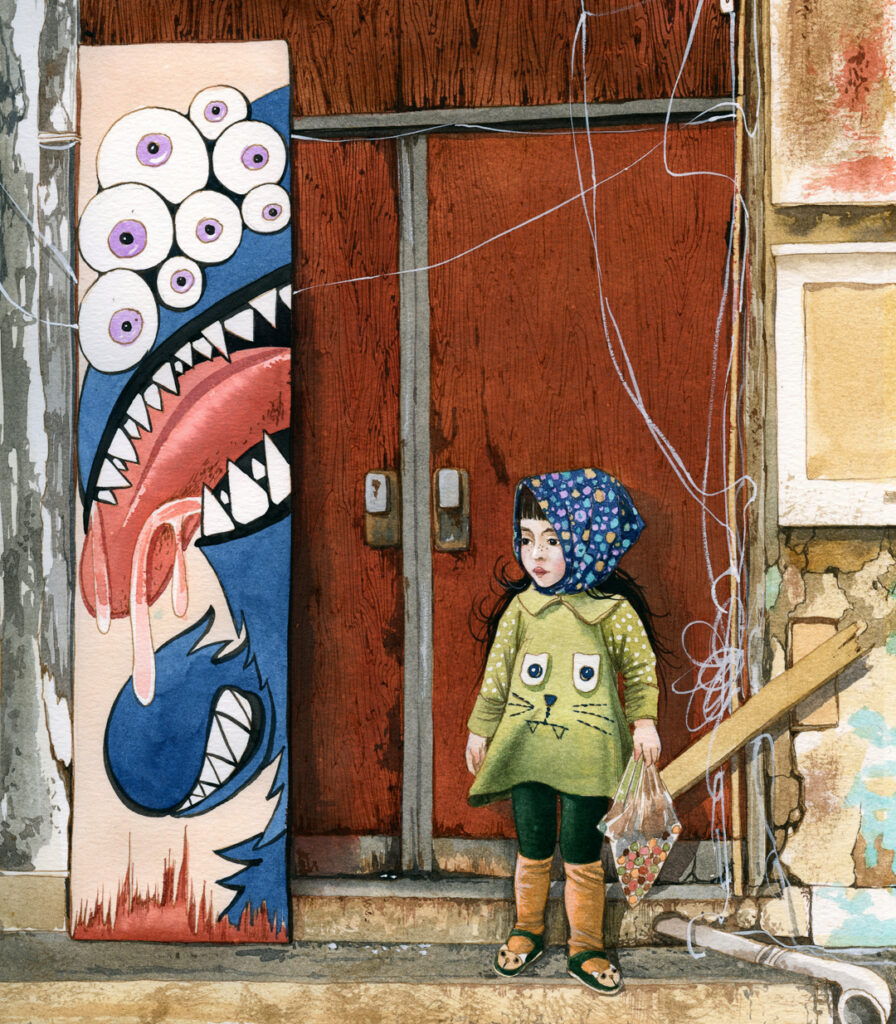

I started drawing these large color images of life in Israel to take my mind off Ukraine. Apart from feeling my life’s meaning taken from under me, like a rug, reality got so absurd with the pandemic and then Ukraine that I couldn’t wrap my head around it. And I took many trips to Tel Aviv at the time in preparation for those exhibitions, which all seemed pointless. After meetings, I just walked around and stared at people and buildings in graffiti and read the walls.

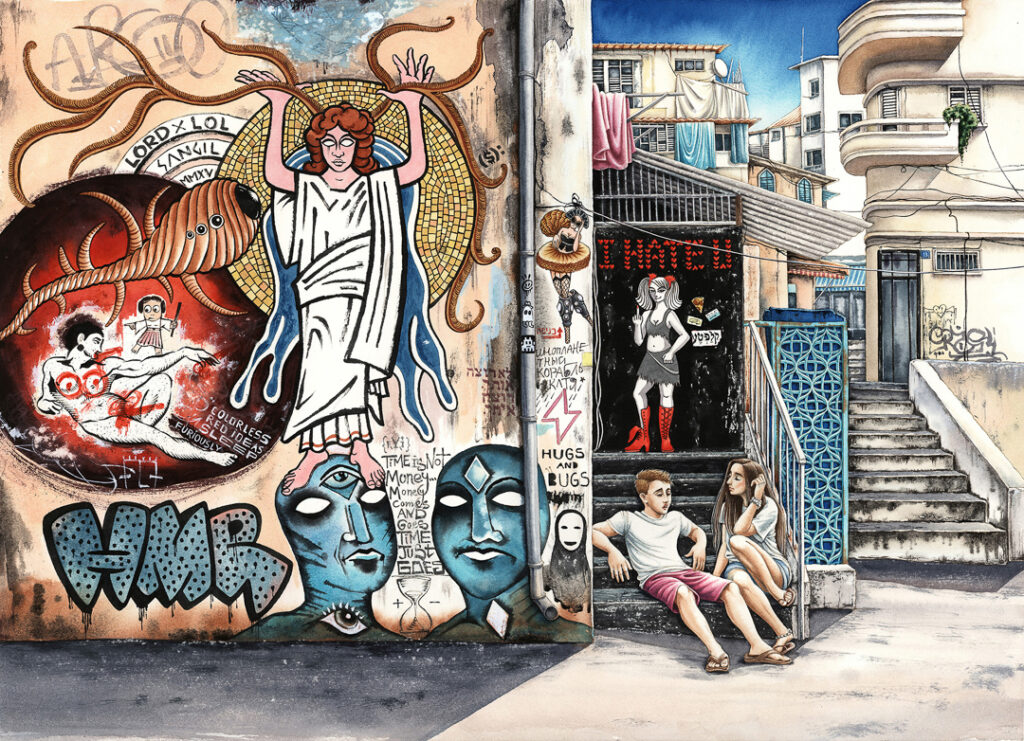

All is real in those drawings. Every little detail. True, I might have combined walls from a couple of buildings in the same area, but it’s all really like that in Tel Aviv. That was actually what blew me away and why all the effort. It’s like walls are talking and messaging a crazy dialogue between buildings that no human mind or AI could possibly come up with: some sort of a kaleidoscope of “eat lsd”, “make beautiful babies”, quotes from Tora, drunk confessions, and portraits of Arthur Rimbaud and Kafka next to Jesus. I thought that’s absolutely the absurd kind of stuff that reflects reality more than anything I could invent to express how perplexed I am at the world. I meant those images as stories that can’t be deciphered, which is what they are in real life and which is what we are all experiencing as we watch the world. I came at it from the angle of “absurd and inscrutable reality”, but every little detail there is from life.

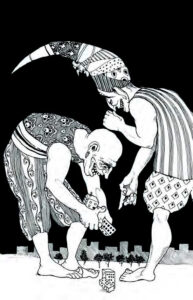

We do what we do, even if it seems useless. I reconciled myself with my own work’s insignificance by realizing I had no other skills. Maybe whatever I am doing is useless, but then I am useless at doing anything else. This one nonessential during wartime thing is the only thing I am good at, so… I’ll continue doing that.

- Sveta Dorosheva, Thou Shalt Laugh

- Original scene for Thou Shalt Laugh

- Sveta Dorosheva, Hugs and bugs

- Original scene for Hugs and Bugs

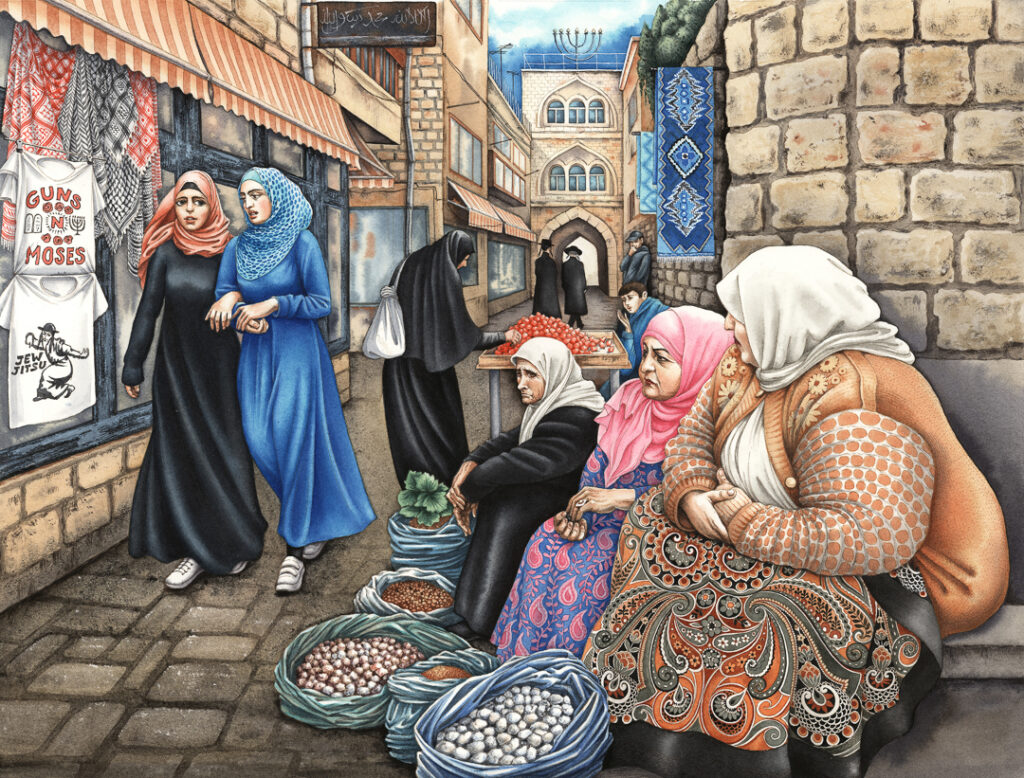

- Sveta Dorosheva, Cola Cart

- Sveta Dorosheva, Aliens

- Sveta Dorosheva, Strawberry Fields Forever

- Sveta Dorosheva, Lockdown

- Sveta Dorosheva, Horse

- Sveta Dorosheva, Candy

- Sveta Dorosheva, Blase Eye of the Hurricane

I had this conversation with an artist friend in Shanghai. She lives there, a local. As she was watching my studio wall filling up with drawings from the streets, she kept asking: “But why are you drawing this?! I mean, it’s beautiful, no question, but why would you pick these scenes to depict? These streets, these buildings, these people? it’s all so… ordinary. I would never have noticed any of this, let alone drawing!” And I was saying “It’s ordinary to you. You live here. Look out the window. Everything you see is astounding news to the rest of the world.”

She was unimpressed until one day I showed her my Israel sketchbook with pencil drawings from the streets (I’ve been doing that for years, and later used some of the sketches for large watercolors). She was mesmerised by those. “But, I said, this is all so very ordinary where I live. Arab women in the street market of Jerusalem, kids crossing the road from school, a street musician, a strawberry vendor, a woman hanging laundry… these buildings, these streets, these people. This is so ordinary where I live, I wouldn’t have noticed any of this, had I not been an immigrant… And it grabs you. The same way I am grabbed by the Shanghai “ordinary” scenes.” She asked me whether I had a series like that about Ukraine. I said no. She laughed and said “I guess, one is blind to a place of birth”.

A similar thing happened later with the Life in Israel series. My parents immigrated to Israel twenty years earlier than myself, so they are way more used to it… When I was drawing the watercolors, mom did not believe me it was all real. She thought I was doing surreal artworks. She doesn’t get out of Rehovot often. So I made a point of taking her to dinner in Tel Aviv, where most of the “raw material” was still right there, on the walls. It’d changed since, but I proved my point then: “See? Here’s Kafka and Jesus and all the crazy dialogue in the messages between buildings, and just look at the people, what a diverse bunch of—” but Mom waved it off and said, “Well, it’s different, because if it’s not a picture in a gallery, why would one notice at all, in all this hustle and bustle?” I said “That’s the whole point”, and mom just gave me The Look. It’s hard to impress your family, you know.

Stone Flowers

Sveta Dorosheva’s only book translated into English is The Land of Stone Flowers A Fairy Guide to the Mythical Human Being (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2018). This book contains fanciful stories of humans as told by fairies. One of these stories is about the places where humans can be found: the “stone flowers”.

People live in giant stone flowers called “cities.”* The veins of the stone flower are called “streets,”** and each is given a name, to avoid confusion. All the veins lead to the center of the flower, weaving and merging together, and the closer to the center they get, the brighter and more magnificent they become. The center is often filled with massive stone stamen that pollinate the clouds.

People live in giant stone flowers called “cities.”* The veins of the stone flower are called “streets,”** and each is given a name, to avoid confusion. All the veins lead to the center of the flower, weaving and merging together, and the closer to the center they get, the brighter and more magnificent they become. The center is often filled with massive stone stamen that pollinate the clouds.

Along each vein stand rows of stone boxes of apes—these are called “buildings.” Each box contains a set of smaller compartments, called “apartments.” This is where humans live. The stone boxes are reminiscent of playing dice, and sometimes, while everyone is asleep, the celestial giants combat their nightly boredom by playing a game of Bones with them. At sunrise, the houses run around on little legs, back to their original spots, so the humans wake up in the same place, with the same view out their windows, and don’t suspect a thing. Sometimes, in the mornings, humans can’t find certain somethings because they’ve rolled into some nook or other during the nightly runabouts.

* Not to be confused with “settees.”

** Not to be confused with “seats.” Settees are seats, while cities have streets.

Visit www.svetadorosheva.com/, follow @sveta_dorosheva_and like facebook.com/draw.lattona.