A Chilean collective has woven tapestries that honour the struggle for justice led by women.

Weaving is a cyclical and persistent process. It does not repeat for the sake of repetition but to learn, repair, and not to forget. Thus, Colectiva Tramando (Spanish: “tramar””, to plot/ to weave), founded by six Chilean women and with over fifty collaborators, invites us to reflect on textiles as a memory and political action device. Through tapestry, an ancestral technique from the Andean mountain range, diverse archives are intertwined to “declassify” Chilean history of the last 50 years, especially during the civic-military dictatorship (1973-1989) and its ongoing consequences.

Curated by Belén Gallardo, Daniela Contreras and Genevieve Tremblay, this exhibition brings together, for the first time, the works of Colectiva Tramando, revealing the immediate, mid-term, and lasting impacts of the dictatorship and the inequalities that endure in Chile today. This exhibition presents a series of essays and perspectives that allow for a deeper understanding of our shared history. Furthermore, Interweaving the Archive challenges us to confront a socio-political rupture that can only be addressed through truth, justice and reparation, paving the way to rewrite a new archive, a new memory, and a new history.

Women in dictatorship

This collective work compiles twenty-four practices of resistance and resilience carried out by women’s groups during the civil-military dictatorship in Chile from 1973 to 1990. Through tapestry, it highlights the protagonists, slogans, and struggles that took place in both public and domestic spaces. Each of the tapestries carries love, promise, and hope, but also confronts us with despair and brutality.

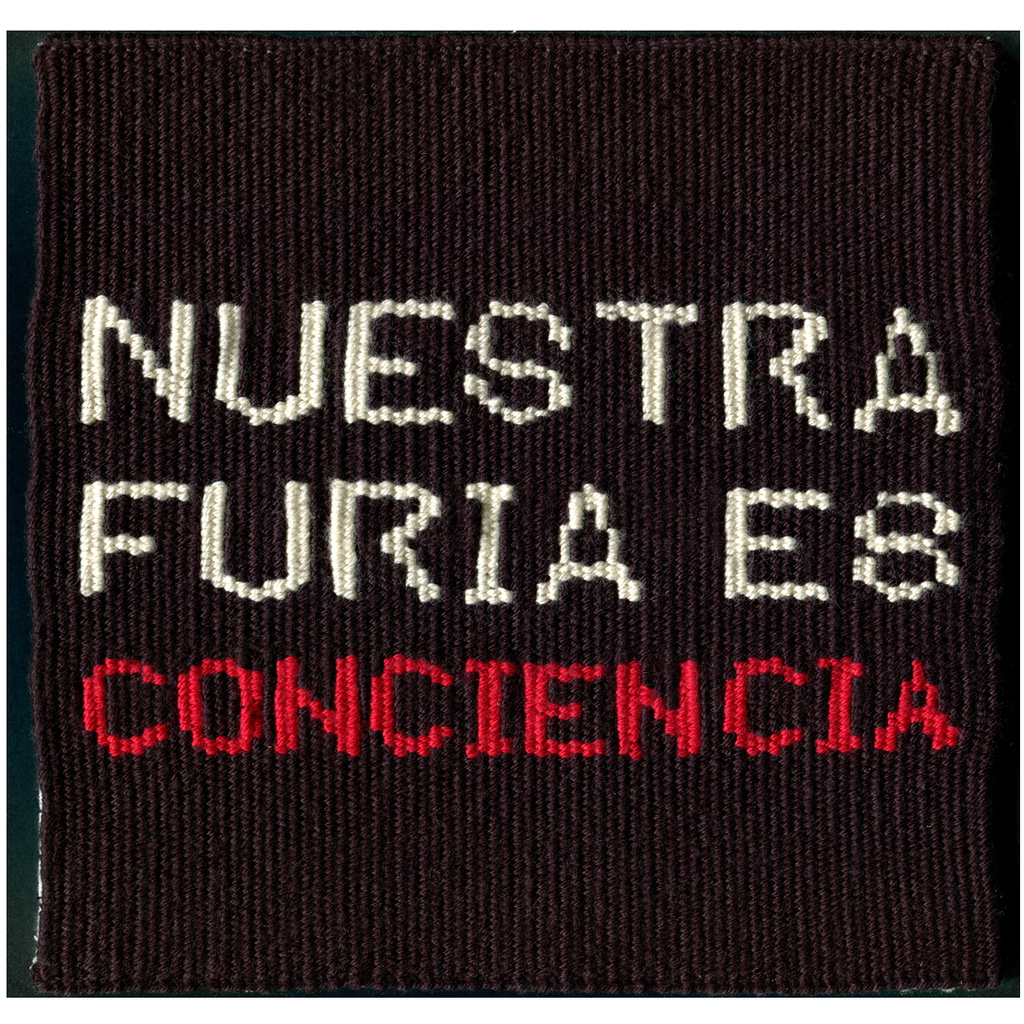

Our Fury is Consciousness

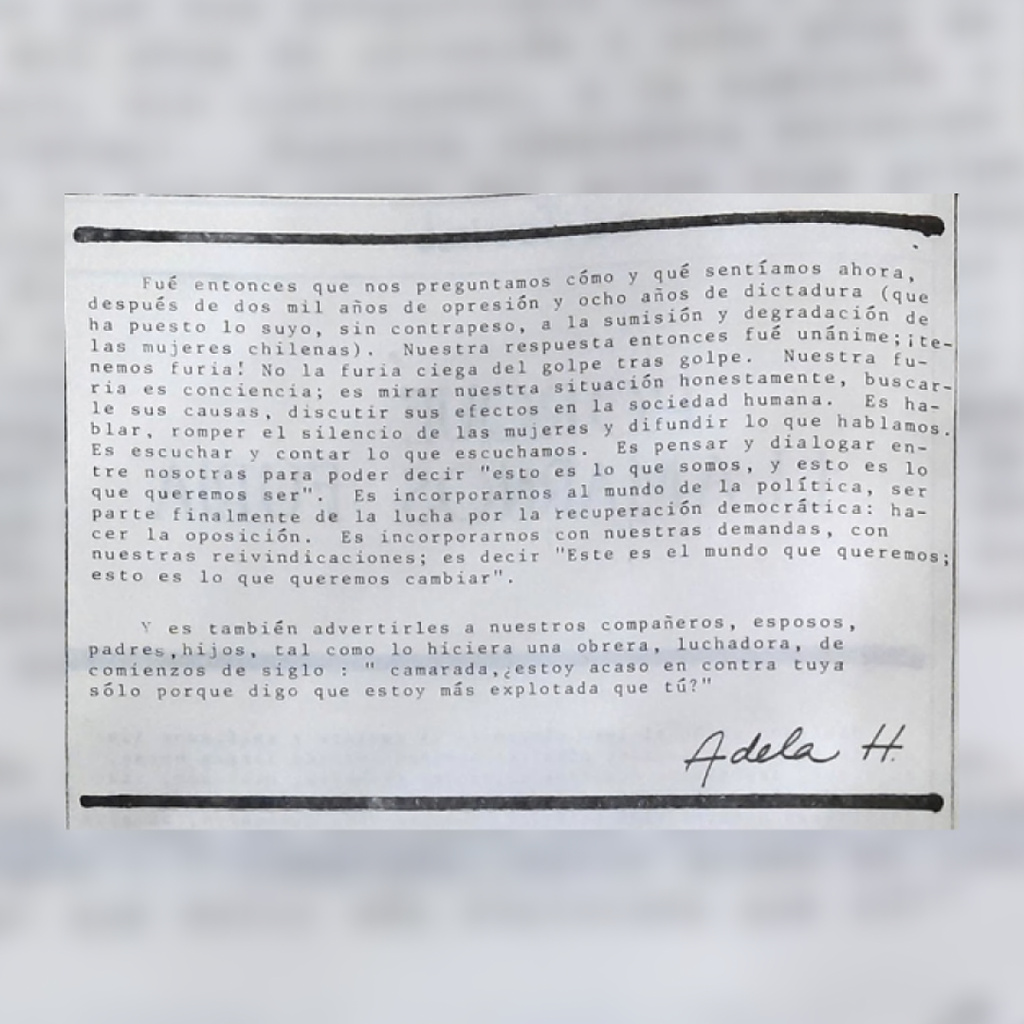

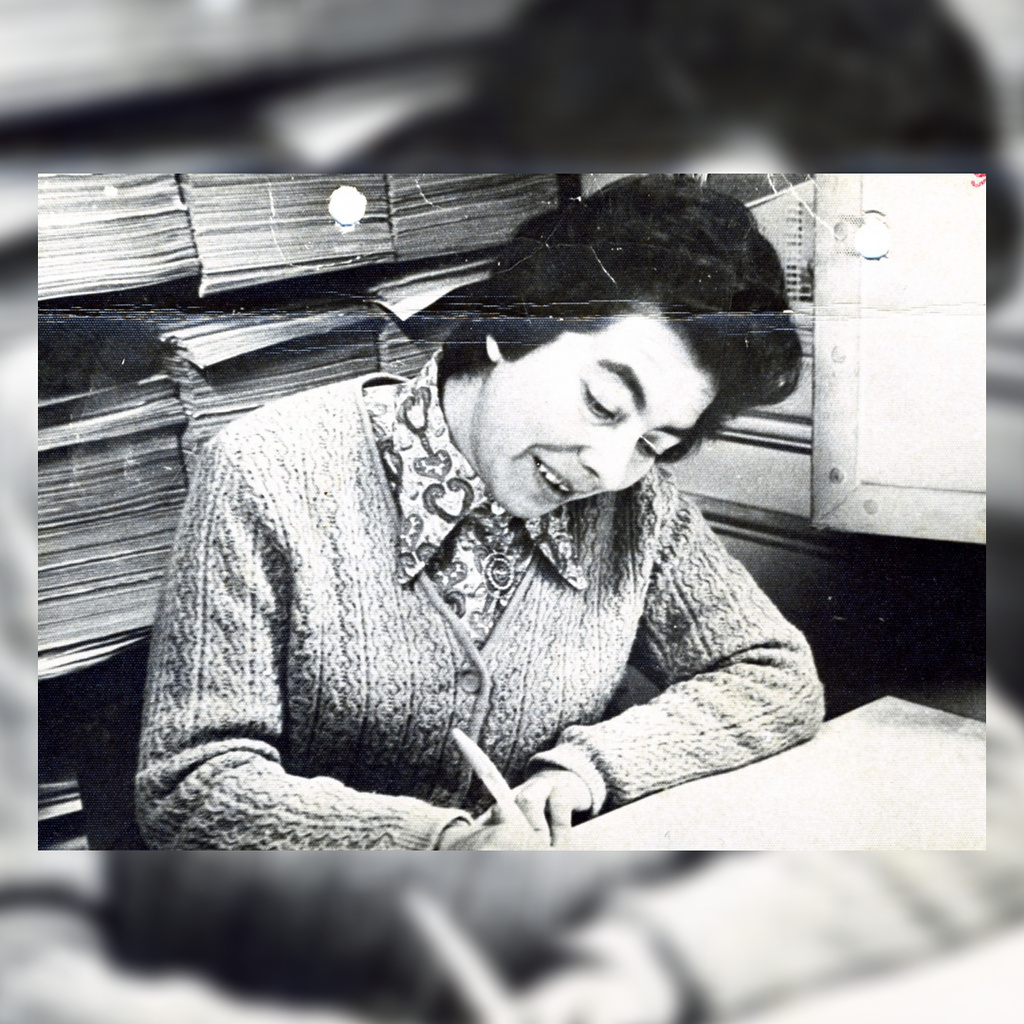

The editorial of the magazine Furia (nº 2, 1981), published clandestinely by a group of socialist feminists, tells how they came up with the name of the publication: they did not want a heroine’s name, but one that expressed what they felt after thousands of years of oppression and eight years of dictatorship, and the answer was unanimous: they felt fury. They claimed this affection, which is traditionally relegated together with all the apparently blind and irrational emotionality to the space of private life, as profoundly political: “Our fury is consciousness”, they said.

Thus was born Furia (1981-1984), a periodical publication in which Julieta Kirkwood, Eugenia Hola, Riet Delsing and Macarena Mack participated, among many other militant women and socialist sympathizers who wrote, illustrated, edited and designed its pages. In her editorials, which Julieta used to write under the pseudonym of Adela H., we can find reflections that still today continue to open paths for the political imagination: “The complex socialist path is more than the path of the State. It is the road through which life is changed”, they said in nº 5, 1983.Furia was one of the various magazines and boletinas (newsletters) with which leftist women’s organizations, working-class women feminists and intellectuals circulated their reflections on the politics of the country and their homes, opening a debate that we continue to sustain and weave today. The complete issues of the digitized magazines can be read at boletinasfeministas.org.

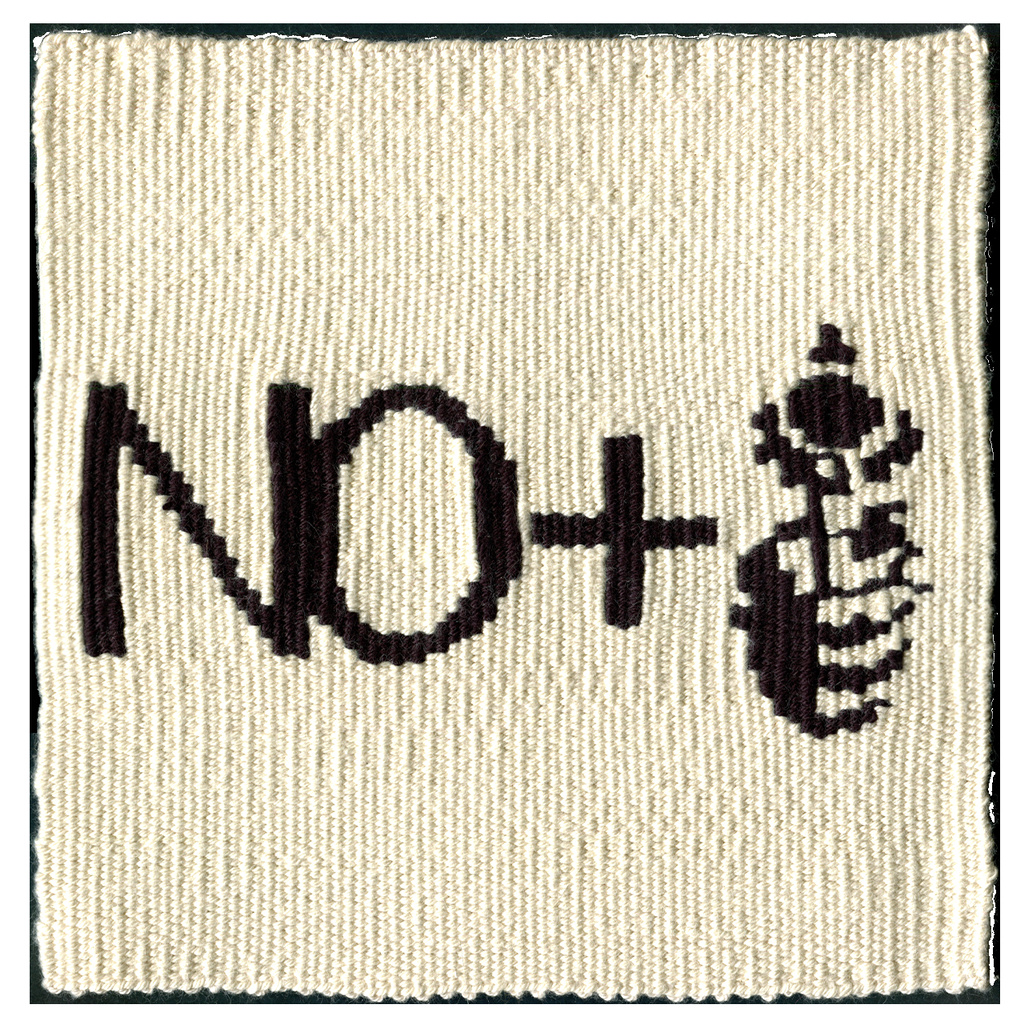

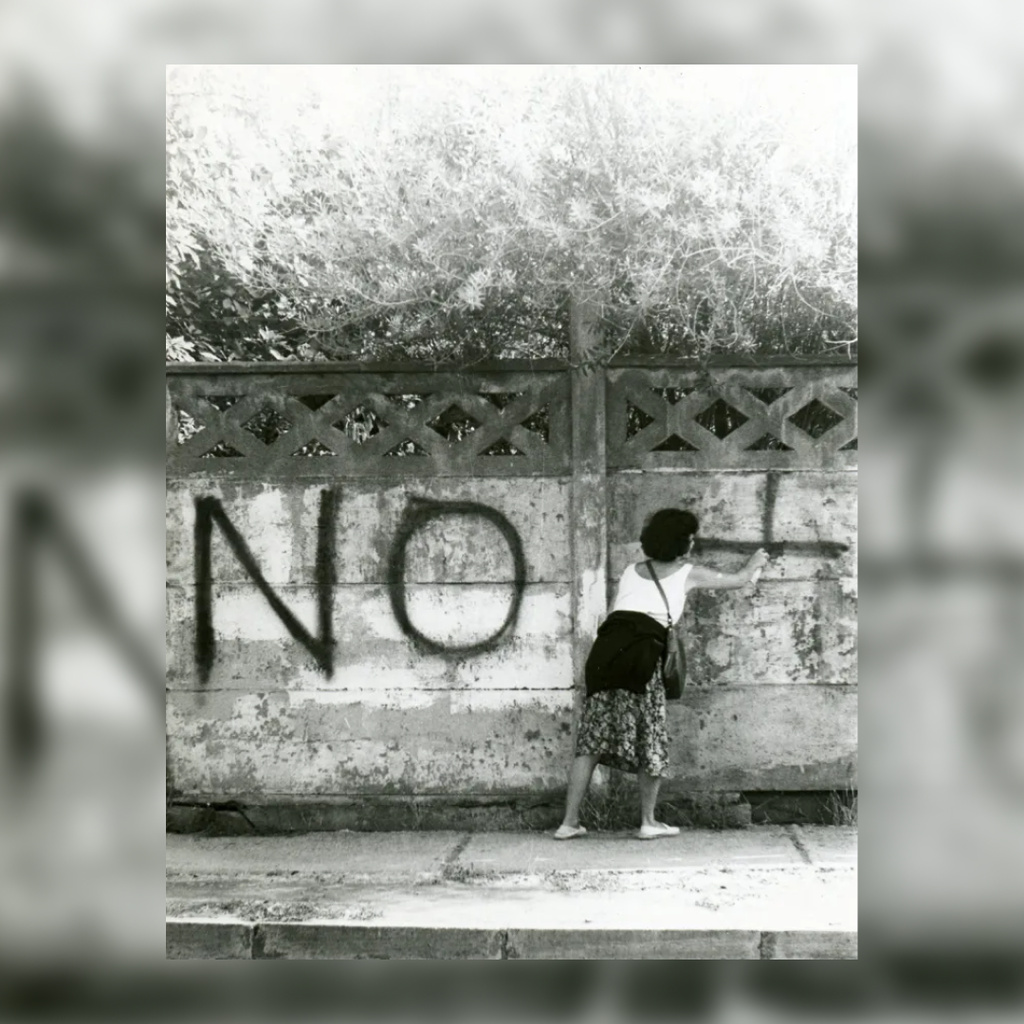

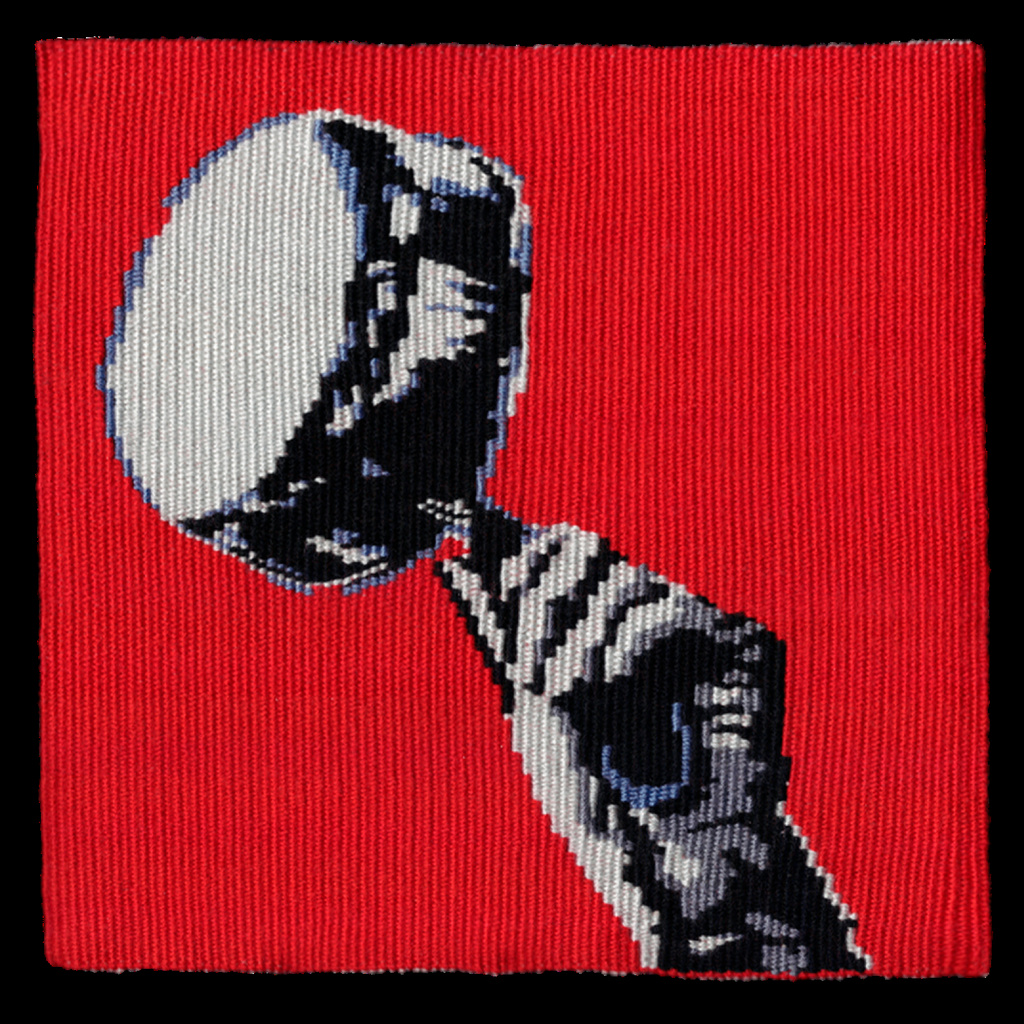

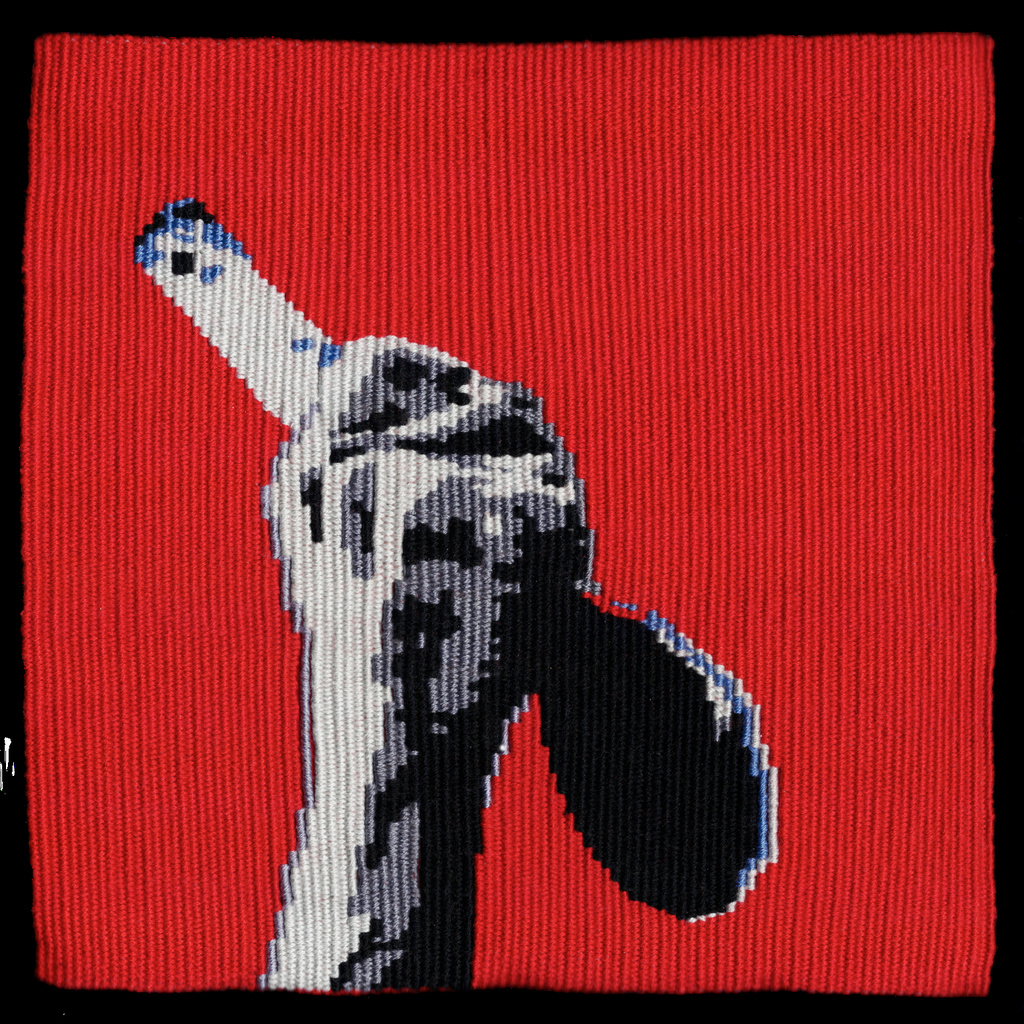

No More

While the country was unravelling, and the presence of fear was instilled through absolute chaos. The actions against the dictatorship of the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte (CADA) persisted, making them into a political force capable of poetically resisting the knots of time. From a social and aesthetic space, the so-called “Escena de avanzada” (Advanced Scene) created the possibilities of art in a political environment—a state of permanent threat, intimidation, censorship, and, of course, attack. However, the power of the collective drives and (re)configurations, articulating manifestos and strategies, show the urgency of a shared commitment to public defense. In this same sense, CADA intensified a practice related to everyday discourses with a symbolic approach, from which messages can be opened and critical imaginaries spread. The piece “No +” (No more) implies a determination. It is a failure, a general cry with a taste of desperation, but simultaneously courageous and fibrous. The making of a small and calculated phrase signals the unbearable situation, and with it, the action to raise simple and eloquent moves that open new formats of protest and popular expression, placing us in a historical reference from which it is possible to move forward.

Meanwhile, a complex and meticulous process is being woven—a process carried out by a production that is acutely aware of the layers and openings revealed by the tensions of its context. This process continues to expand, up to the present day, through new re-presentations of art that have historically circulated along surviving paths.

Meanwhile, contingency mobilizes us through uses and functions that vary according to need, ability, or desire. It incorporates a universe of variable techniques, where the work itself is recharged (in this case, through a new medium such as tapestry) without losing the lucidity of the image and the clarity of its discourse.

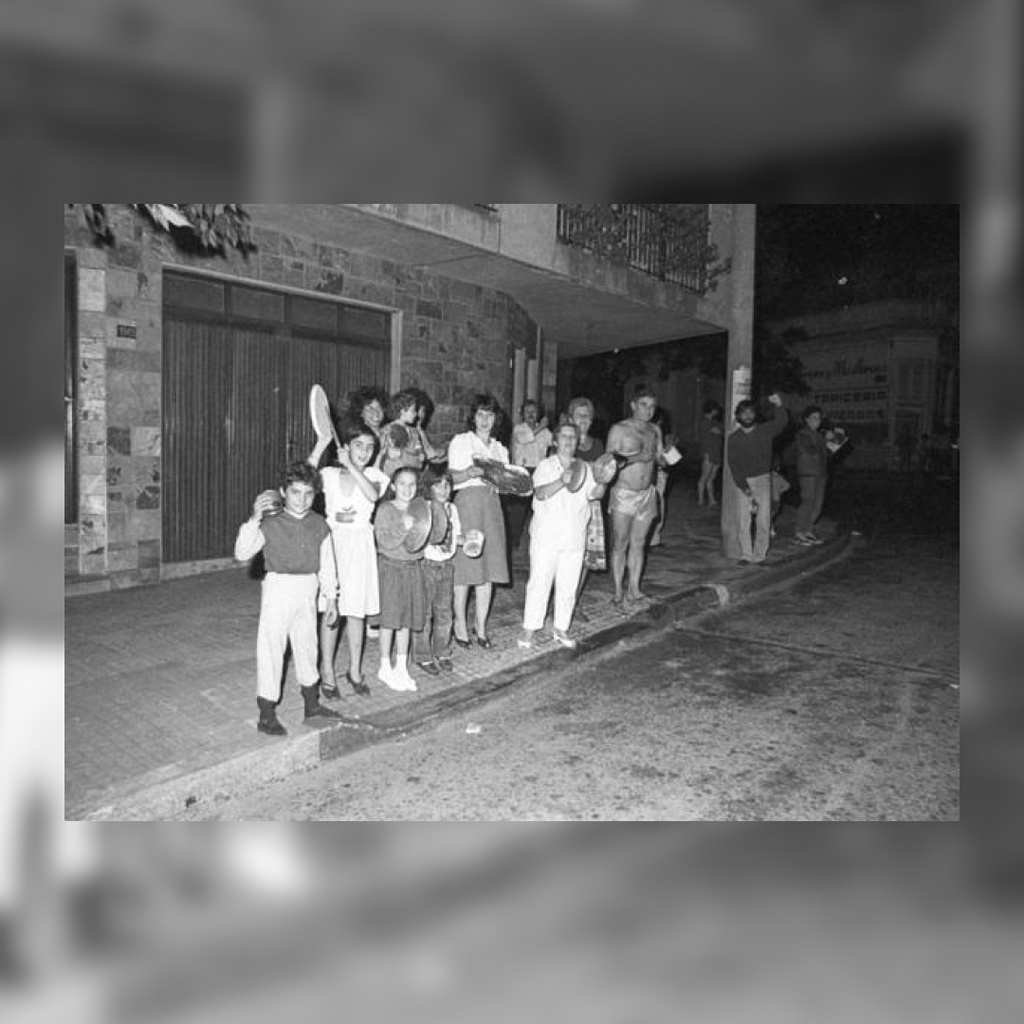

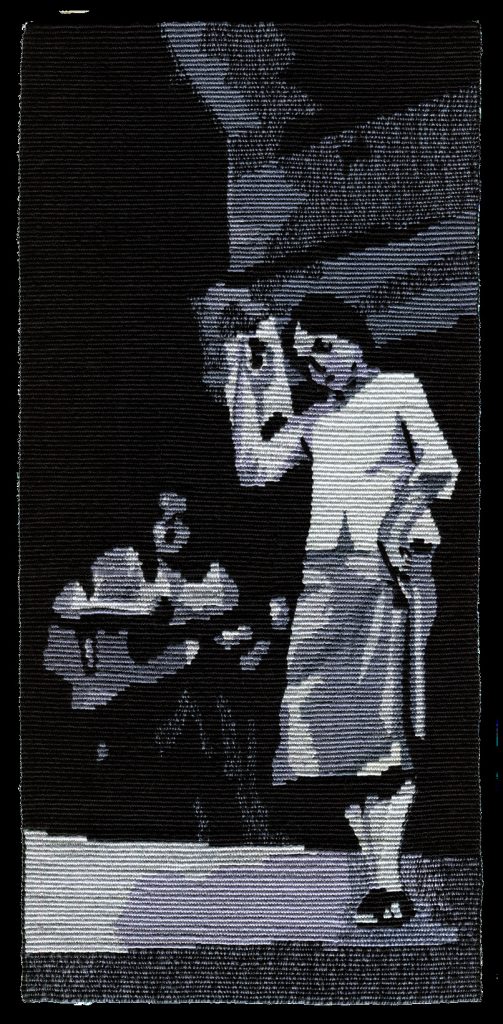

Protesting with Saucepans

Two pot lids are being used to sound like cymbals, as a tool to generate sound, noise, to be heard. The tapestry shows what was a common form of protest: at the agreed time, from the windows of houses and apartments throughout the country, citizens banged their pots and pans as an institutionalized way of demonstrating rejection to the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

The method is not exclusive to Chile: historians have traced its origin to France in the nineteenth century. And it extends beyond the dictatorial era: this form of protest was resumed during the popular revolt of 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, Chileans adopted this way of demonstrating and made it their own in the ’70s and ’80s for a logical and simple reason: with a curfew in force during most of the years of dictatorship, going out to protest on the streets was not allowed and, if you dared to do it, it became a high-risk activity that could end in disappearance or death. “Cacerolear” was a way to join the national sentiment against the military regime from the confinement imposed by the same regime.

The banging of pots and pans became common, especially in the twelve National Protest Days that took place between 1983 and 1986, which included strikes, street demonstrations and intervention in public spaces during the day, in addition to massive and resounding bangs of pans at 8:00 p.m. The sound of pots, wooden spoons and pot lids was replicated in the different territories of Santiago, but also in cities outside the Metropolitan Region. With the same metallic roar, the locked-down nation said “no” in unison to Augusto Pinochet and his tyranny.

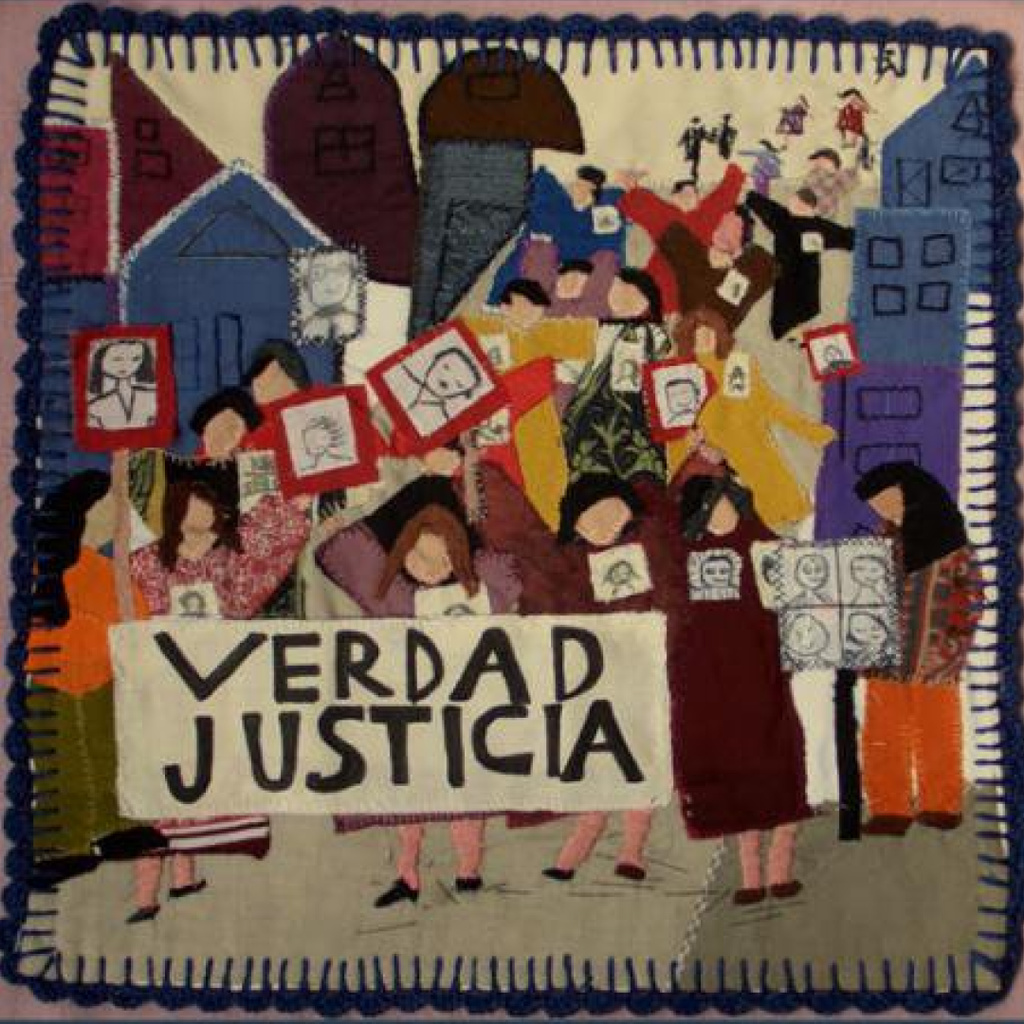

I demand the truth in an arpillera

To narrate horror through textile scraps on a flour sack base. Such was the challenge that sculptor Valentina Bone proposed upon her arrival at the “Pro Paz” (Pro Peace) Committee in 1974. At that time, the ecumenical institution provided technical, legal and spiritual support, mainly to women whose relatives had been disappeared by the Chilean civil-military dictatorship and for whom human rights violations were part of their daily stories.

In a work that was not exempt from collaboration and attentive listening, the arpilleras implied the unveiling of women’s narrative that, through threads and needles, allowed the unspeakable to be said. According to Valentina, the arpilleristas embroidered pages of life diaries. In this biographical intimacy, the Andean mountain range became a distinctive element, ensuring that the events represented took place in Chile, which became important since these works travelled clandestinely abroad, where they became tools of denunciation and monetary exchange in solidarity events promoted by organizations or committees of exiled Chileans and galleries.

In 1975, the proliferation of workshops throughout the Metropolitan Region resulted in a thematic diversification. These new embroideries confronted the spectator with community communal soup kitchens, laundry rooms, or children’s free food programs, where children and mothers were protagonists. Although official history has cut out these achievements, the women shared their scraps, pains, and food amid barricades and textile subversion.

Several testimonies affirm that the arpilleras allowed them to take control of their lives economically. This is not a minor point since several arpilleristas suffered domestic violence. The trade allowed them to support each other. Under the dictatorship, thousands of anonymous women wove together community and gender networks, focused on the struggle to survive: “I don’t want anything for me that is not for everyone.”

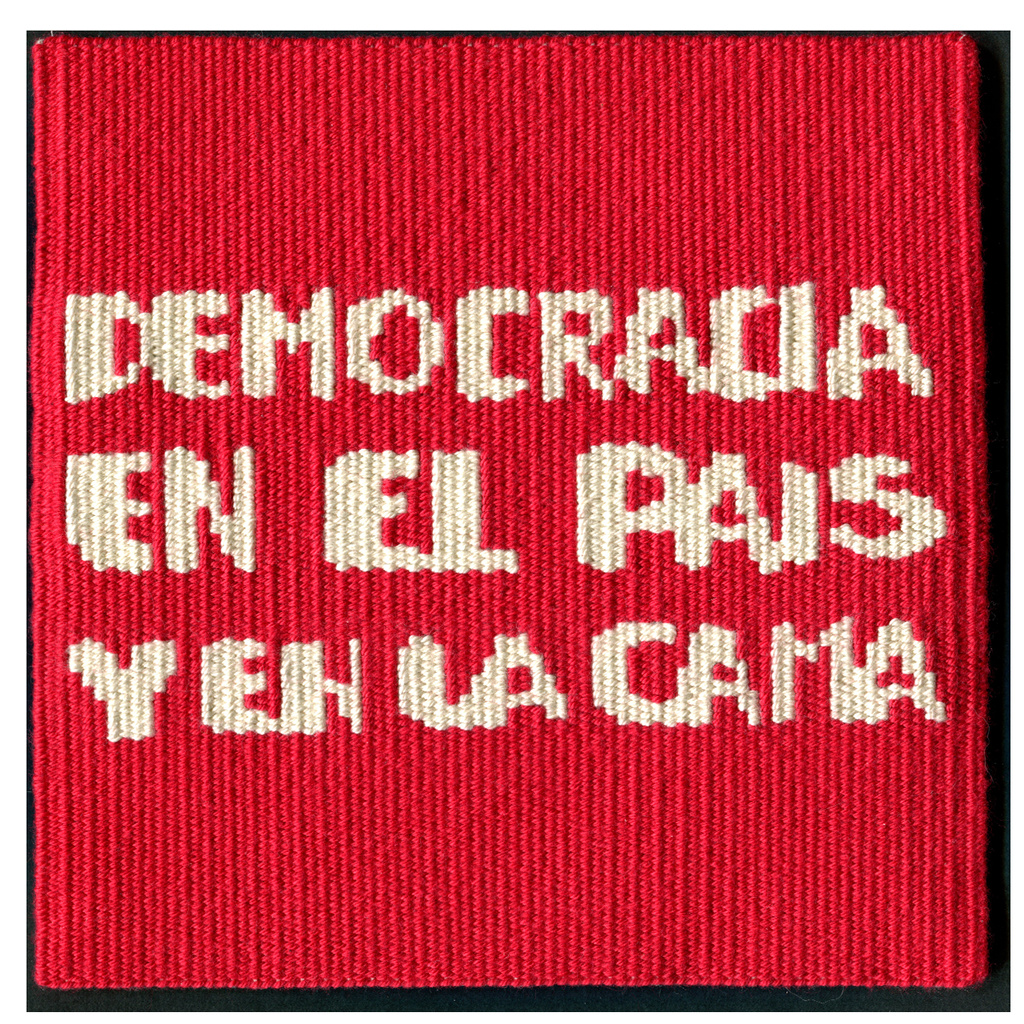

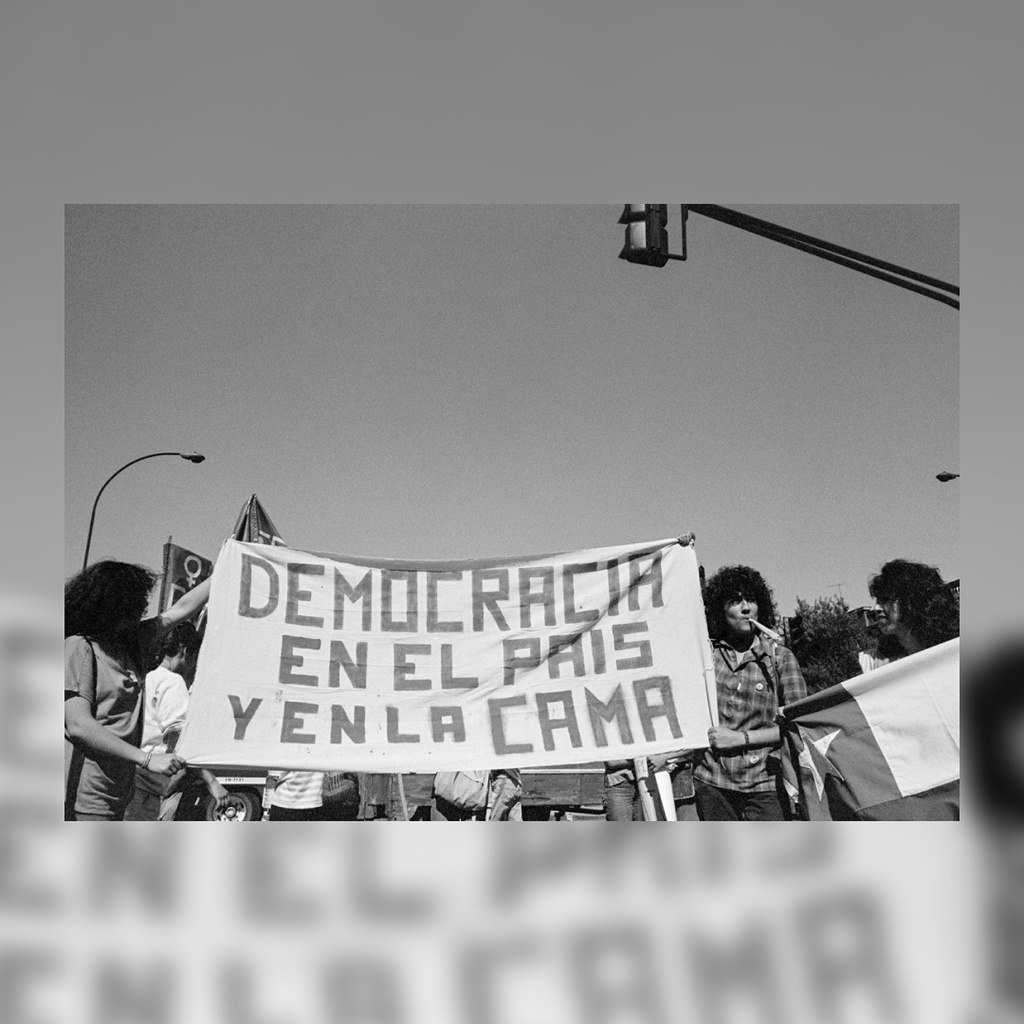

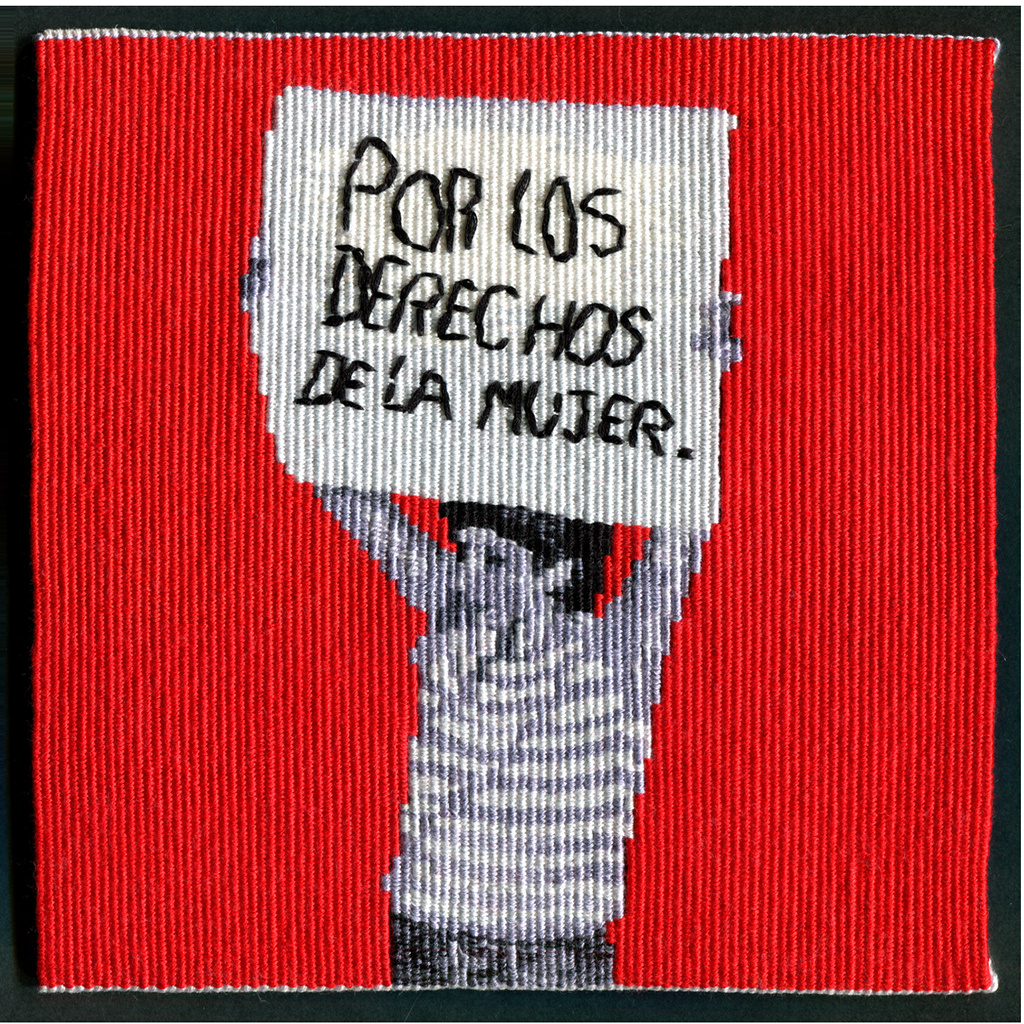

Democracy in the country and bed

In Chile, like in the rest of the world, we can distinguish different waves of feminism, which are closely related to the historical context of which they are part. Thus, if the first feminist wave was characterized by uniting the voices of different women who demanded women’s suffrage, the second wave was marked by the context of the civil-military dictatorship and opposition movements to it, mainly denouncing violations of human rights.

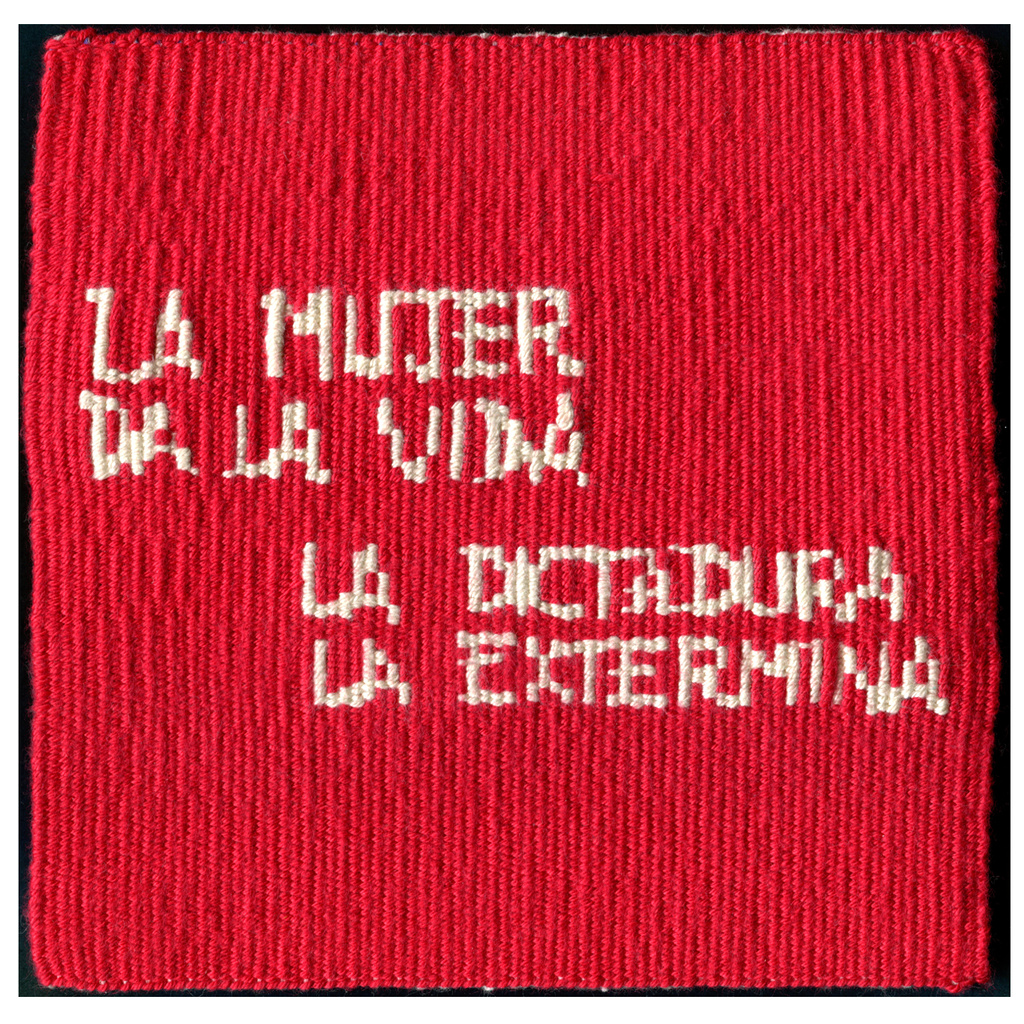

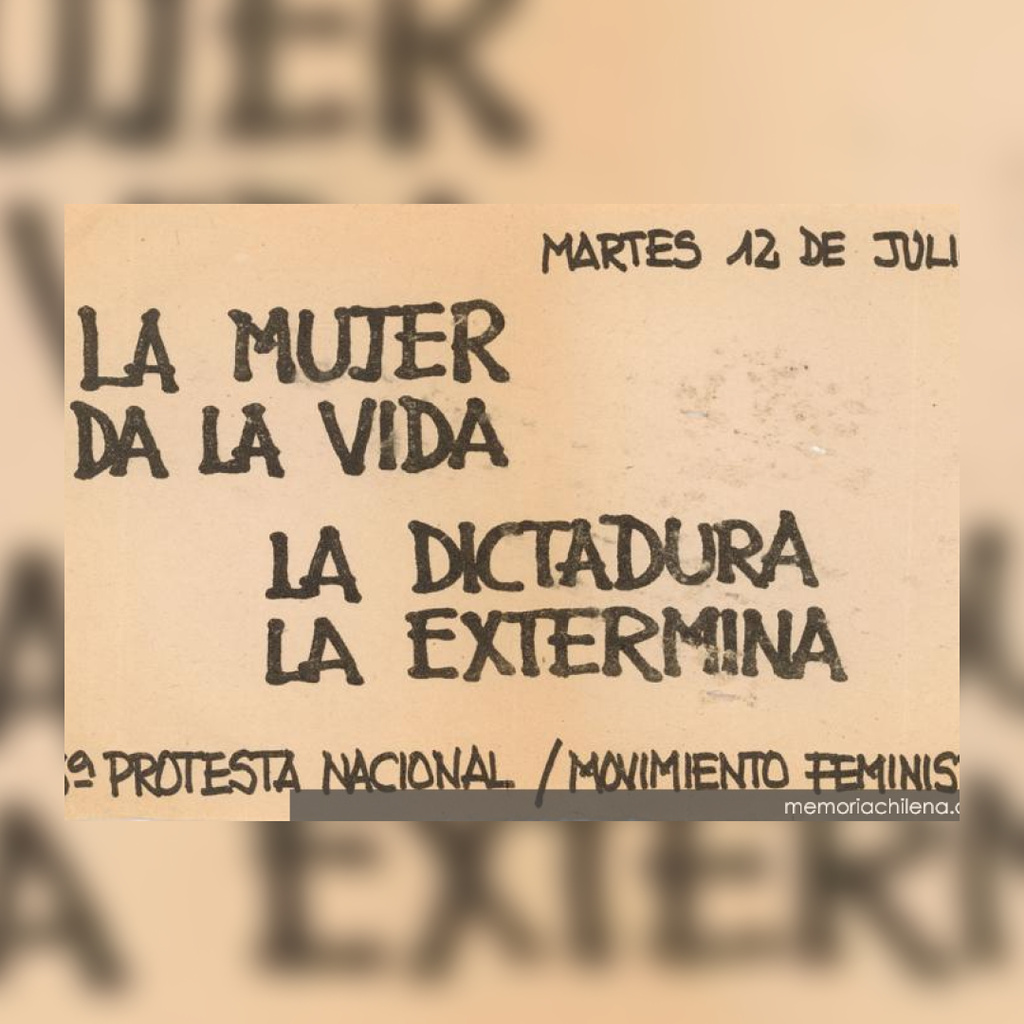

Through pamphlets and public participation, women’s groups raised their voices against the atrocities suffered in the country. Since the media was favorable to the regime and did not cover the reality, the streets became the space to spread the demands, which were not only restricted to the return to democracy, but also to the transformation of the social role of women. With this, slogans such as “Democracy in the country and in bed” or “Woman gives life, the dictatorship exterminates it” emerged, in which the importance of Democracy was expressed to advance the questioning of gender roles, and at the same time, the participation of women to ensure democracy.

In this process, the work of women such as Julieta Kirkwood, a sociologist and political scientist at the University of Chile, became relevant, questioning the role of women in the public space and defending the idea that without feminism there is no democracy. Affirming there should be spaces for female participation in politics, to ensure social transformation. Although this was evident during the 80s, it is a vision that could be extrapolated to today, where gender roles and women’s participation in politics continue to be questioned.

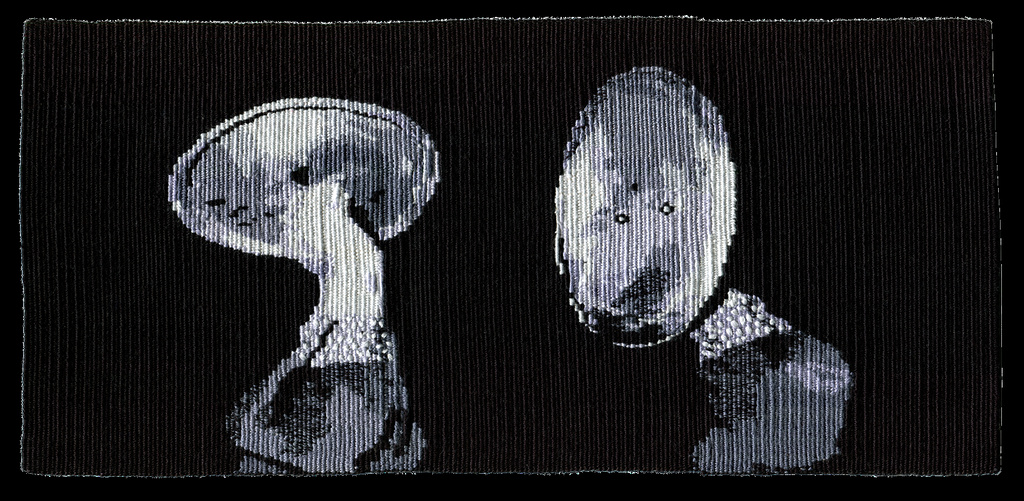

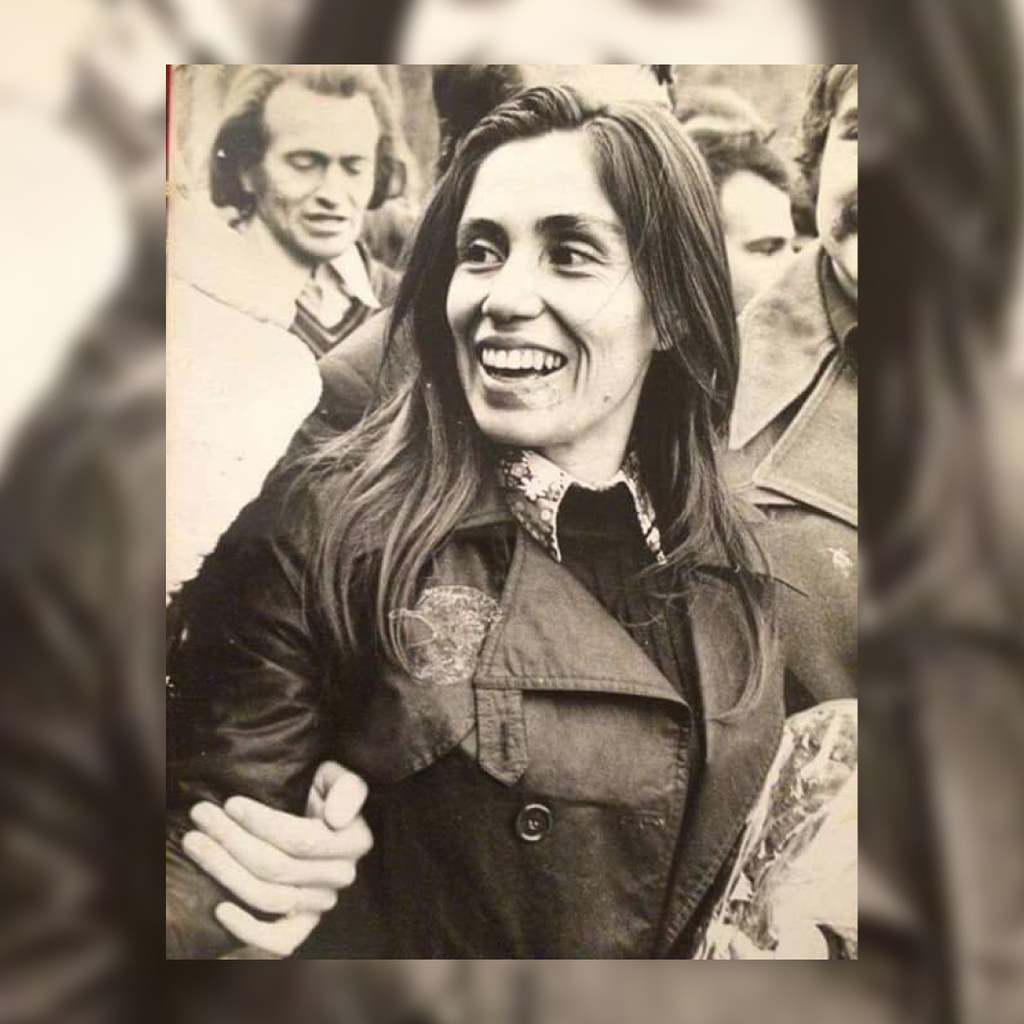

Gladys Marín

Educator, politician, mother, militant, communist leader, presidential candidate and social fighter. These are just some of the facets of Gladys Marín Millie (Curepto, July 18, 1937 – Santiago, March 6, 2005), who you can see today in this piece of textile, whose constancy, charisma, and recognition have made her an iconic and transcendental figure in Chilean politics. Her outstanding career includes being the first woman in the world to become General Secretary of the Communist Party, the same party for which she was a Deputy before and after the coup d’état, in addition to being President of the Communist Youth. For that same social recognition, she was one of the most sought-after people during the dictatorship. In this context of persecution, Gladys Marín found it difficult to hide because of, among other things, a particular characteristic: her smile, which is also portrayed in this piece of tapestry.

After September 11, 1973, Gladys Marín requested asylum at the Dutch embassy, and later went into exile. In 1978, after denouncing human rights violations in Chile in various countries, she returned in secrecy to fight against the dictatorship, as leader of the internal leadership of the CP. “We must fight, fight, and continue to fight, even if our lives are at stake,” is one of her most memorable phrases. Gladys’ smile. A warm smile that shows the serenity of someone who has fought for her convictions from a collective point of view, of someone who has overcome the worst atrocities, such as the murder of her comrade Jorge Muñoz Poutays, her life in hiding, exile, among others… In this textile piece, as well as in photographs, books, stencils and other portraits, her smile stands out, conveying the warmth of that same gesture.

Seahorse

Throughout the twentieth century, the bronze grid of the seahorse was one of those common elements in Chilean homes, like the Penco china or the painting of the Crying Child, elements of an emotional and daily memory that configured in the collective an idea of the homely, the known and protected space of the domestic. Its participation in Chilean real estate was so massive that it slipped silently and humbly into the spaces that were dismantled to be used as torture centers. Especially in the bathrooms, which were the place where the prisoners could take off their blindfolds and find some relief from their suffering. There, they could wash themselves and maintain a minimum of hygiene. Sometimes the prisoners could also put into practice strategies of solidarity that they had developed to try to escape sexual violence. Always under surveillance, the appearance of the metallic seahorse became a point of escape from so much horror.

Perhaps the memory of home, the memories of a past life, or the imagination of a connection with those who waited and searched for them outside. The longing for freedom and the search for hope found a point of support in the tender figure of the seahorse, one of the few that could be found in a situation of such cruelty. Today, the memory of the survivors around the common experience of the bronze seahorse is also a testimony of resistance in the face of adversity, which finds a place in small objects to elaborate resilience. The persistence of the grid in many houses in Chile allows us to connect with this memory and this lesson of humanity.

Dancing cueca by oneself

Gabriela Bravo, dancing for Carlos Lorca Tobar, her husband, father of her son, socialist lawmaker, who became a disappeared detainee on June 25, 1975. Alongside her and playing guitar is Patricia Paredes, who played for Ricardo Lagos Salinas, her husband, socialist militant, a disappeared detainee since June 17, 1975. Gabriela joined the Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos (Association of Disappeared Detainee Relatives), in which Gala Torres, director of the group, played, sang and danced for her brother Ruperto Oriol Torres Aravena, disappeared since October 13, 1973, and produced the Cueca Sola.

The photograph that immortalizes this encounter was taken by Luis Navarro, photographer of the Vicariate of Solidarity, in 1978. Gala sings and Gabriela dances: “Oh dear once I was happy / oh dear peaceful were my days (bis) / oh dear but calamity befell / oh dear I lost what I loved most / oh dear once I was happy // I constantly ask myself / where do they have you / and nobody answers me and you do not come / I constantly ask myself / where do they have you // and you do not come // and you do not come my love / long is the absence / and all over Earth / I ask for conscience / without you dearest garment / all life is but lost.”Their first performance was set for Women’s Day, on March 8, 1978, at the Caupolicán Theater.

The cueca had been established as the official national dance within the framework of the cultural policy of the civil-military dictatorship, through its promulgation of decree No. 23, published in the Official Gazette on September 17, 1979.

The gesture of the women raising the white handkerchief is not of surrender. Special thanks to Victoria Díaz, member of the Folkloric Ensemble of the AFDD, daughter of Víctor Manuel Díaz López, disappeared since May 12, 1976, who kindly provided valuable information for this summary.

Hooded Girl Holding a Flag

Some words are difficult. Perhaps because we don’t really know what they mean, or, on the contrary, because we know exactly what they mean. Something similar is true for Resistencia. Resisting, as a political category, has a very delimited conceptual framework: from Gramsci onwards, resistance has been seen by social sciences as the possibilities of subaltern groups to dispute political, cultural and economic hegemony, among others. Its use, mainly in the sixties, seventies and eighties in Latin America, was also tantamount to “just violence” (Hinner, 2015), and, in the collective imagination, it acknowledges one particular figure: the militant-man. In the last thirty years, research in this subject—led mainly by women—has complemented the classic figure associated with resistance with that of the militant-woman (Troncoso, 2020) and the link between historical memory and gender.

Thus, from feminisms it has been possible to weave the stories of resistances from situated analytical frameworks that recognize life stories, minuscule stories, solidarities and affections as spaces of resistance to the civil-military dictatorship in Chile. The two images that elicit this collective dialogue invite me precisely to do just that: to decompose the representation of resistance in Dictatorship, in order to imagine resistant bodies with hoods and beads. Shouting and in silence. Skirts and pants. With purses and backpacks. And deterritorialize their emergency to reflect on vivid resistances, past and recent, with Chilean, Mapuche and gender-based dissident flags, and to think of resistance as an embodiment of a political-ethical act.

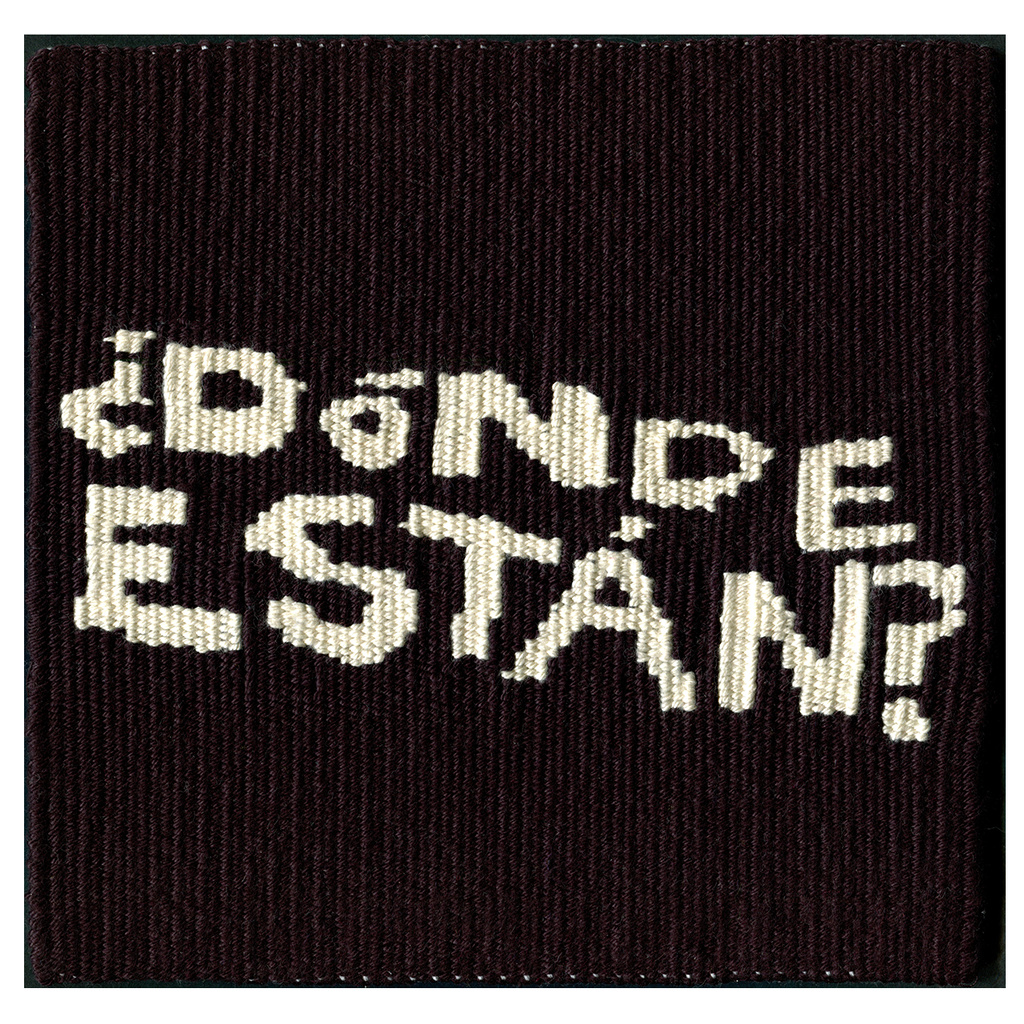

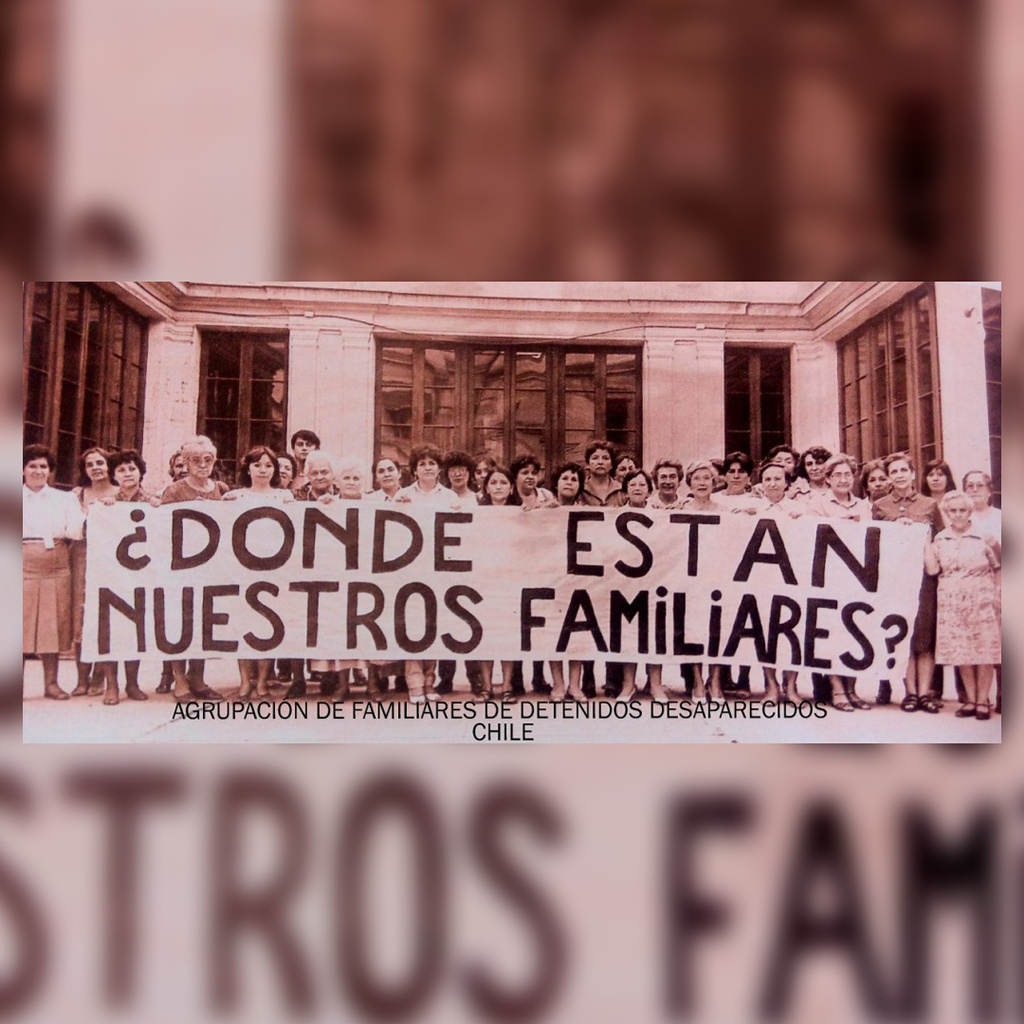

Where are they?

We approached the secret of shame. Where are they, we asked. The answer was a spit, a threat. We asked God where they were imprisoned. On what side of his wretched design? We kept our suspicions secret. To confess them would have meant entering the house with knives. To fall on our knees. To throw the question on the floor and stomp on it: Where are they? We know that you saw them humiliated. That you heard them screaming the names of their children. Where are they? On the black tile. Where is the tile? Under the soldier’s boot. Where is the soldier? In the cellar of the homeland. Where are they now? In what ruins of the homeland? At the bottom of the sea, they said. In the soldier’s nightmare. In the excrement of fish and worms.

Where? In the majestic question. In the imperative. Say where. In the speculative answer. In the minutes of distracted silence. In the poem’s insistence. In the infectious imagination. In the interrupted kiss. In the frivolously tortured movie. In our sadness. In the gallery. In the written battle. Where are their cries? In what redundant deaths, versions of a replicated death? Everywhere, they say, in the faded photos, in the erased photos, in the suicidal idea. Probably in memory, which melts like wet paper. Scattered in the air like ashes. In our burial. In the dry tears. In oblivion. In the violent school composition. In the confession that frightens the priest. In the eyes of the gagged priest. In the priest who hangs up his cassock. In the soldier who deserts. In the music that stops from one moment to the next. In the sky, spinning senselessly. In the quarrel. In the scream that explodes like a bomb. In the dead of that bomb. In the wounded, where are they, we say? In the flag of a faraway country. In the museum. In the wall. In the concert. In the concert brochure. In the shared publication. In the rage. In the like. In the eyes glued to the screen. In the screen that asks: Where are they?

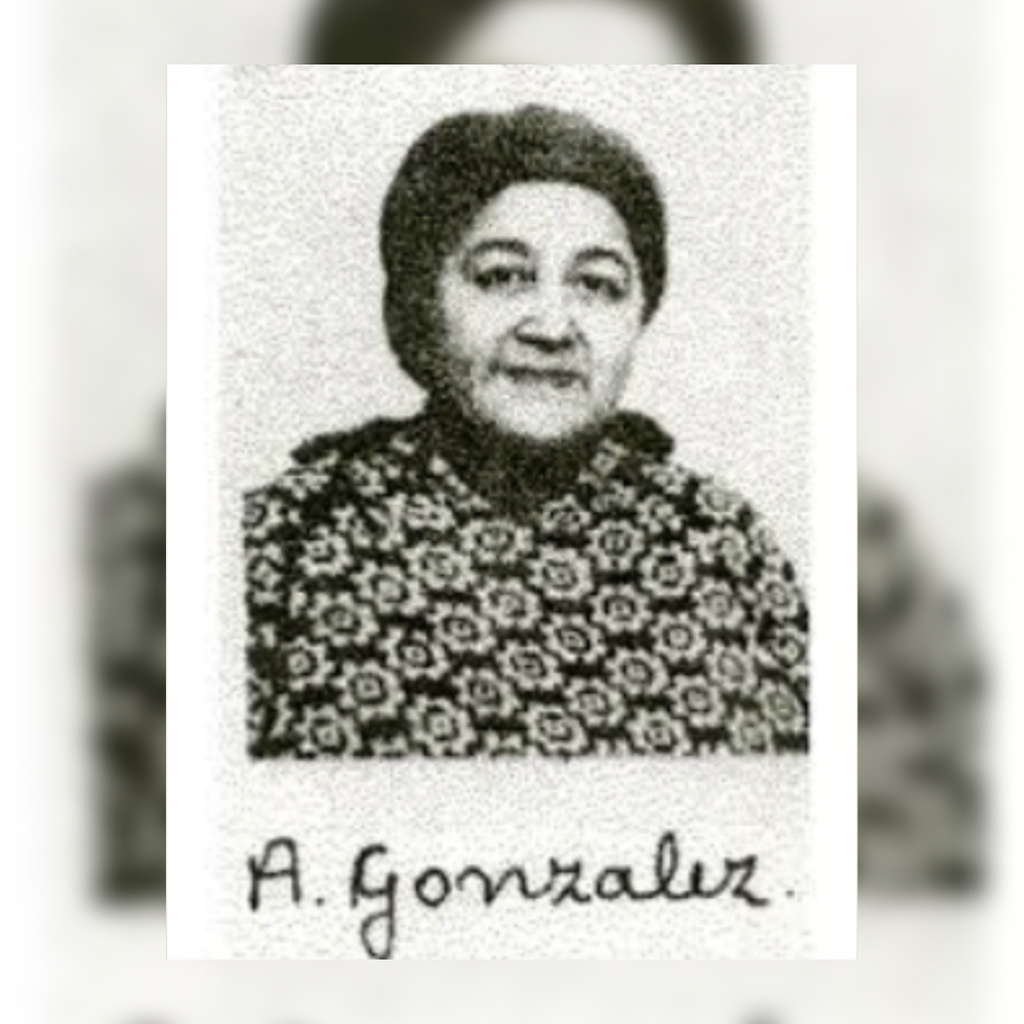

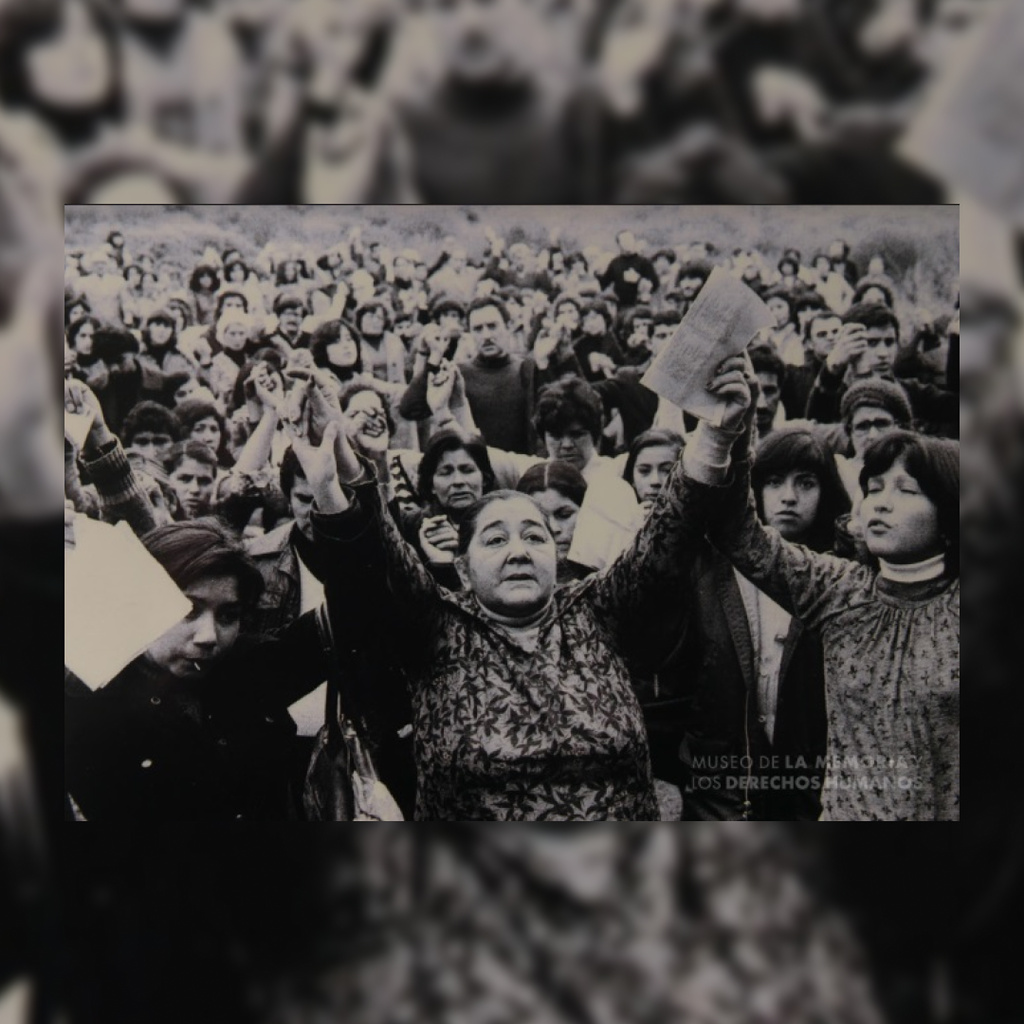

Ana González

Ana González González is a woman who embodied with deep and tireless courage more than 40 years of struggle against oblivion, injustice and impunity. She was born in the Toco Saltpeter Office (Chilean Nitrate) on July 26, 1925. With the collapse of the saltpeter, she and her proletarian family moved to Tocopilla. She then migrated to Santiago, where she continued her education in humanities, while helping her aunt with the sewing trade. It was also in this city where she met and fell in love with Manuel Recabarren, with whom she formed a home. She worked from the grassroots to end social inequalities in order to dignify life in this country called Chile. That is why, together with her family, she committed herself to the program of the Unidad Popular and the government of Salvador Allende.

In 1976, the civil-military dictatorship kidnapped and disappeared her family. Her husband Manuel, her sons Luis Emilio and Manuel and her daughter-in-law Nalvia, who was pregnant, were taken from her everyday life. They never returned. Since then, she has courageously and fervently defended the Human Rights of an entire people. Truth and justice, “nothing more, but nothing less” she demanded until her last days, activist, advocate, searcher. “We must search in order not to lose hope, even among ourselves, among simple encounters,” she said. From that conviction, she never stopped sheltering spaces of fraternal resistance. She founded the Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos, participated in the first hunger strike in CEPAL, denounced in various institutions such as the United Nations, OAS, International Red Cross, International Commission of Jurists, Vatican, Amnesty International and the media. Memory, justice, truth.

Despite the pain, she persevered in clarifying the circumstances of the disappearance and the final fate of her people. Always with a rebellious dignity and a strong connection to life “(…). She died in Santiago on October 26, 2018, at the age of 93, without finding her family. But she left a great legacy, courageously carrying the image of her loved ones on her chest, in every march, in every speech, in every protest… in every raised fist. Thank you, Ana, for never ceasing to fight against oblivion, for persevering in the search for truth and justice.

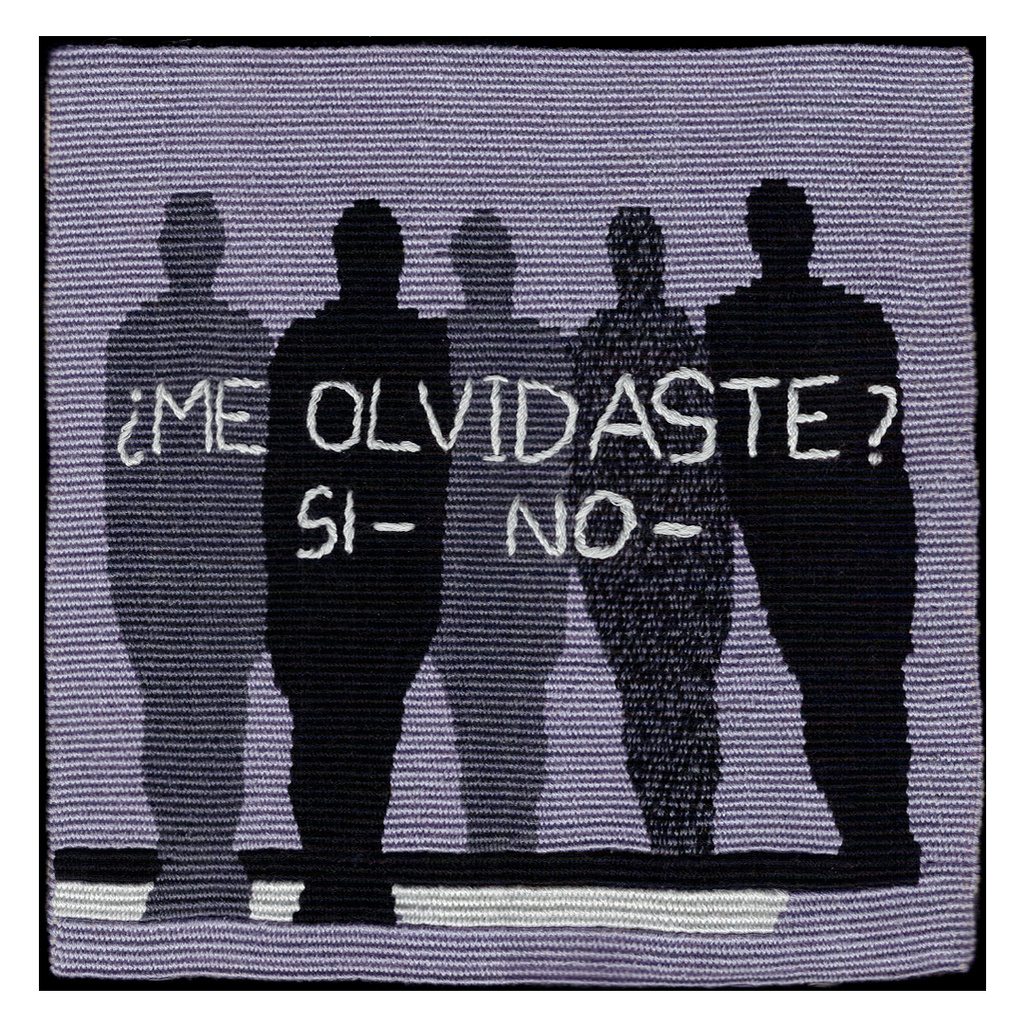

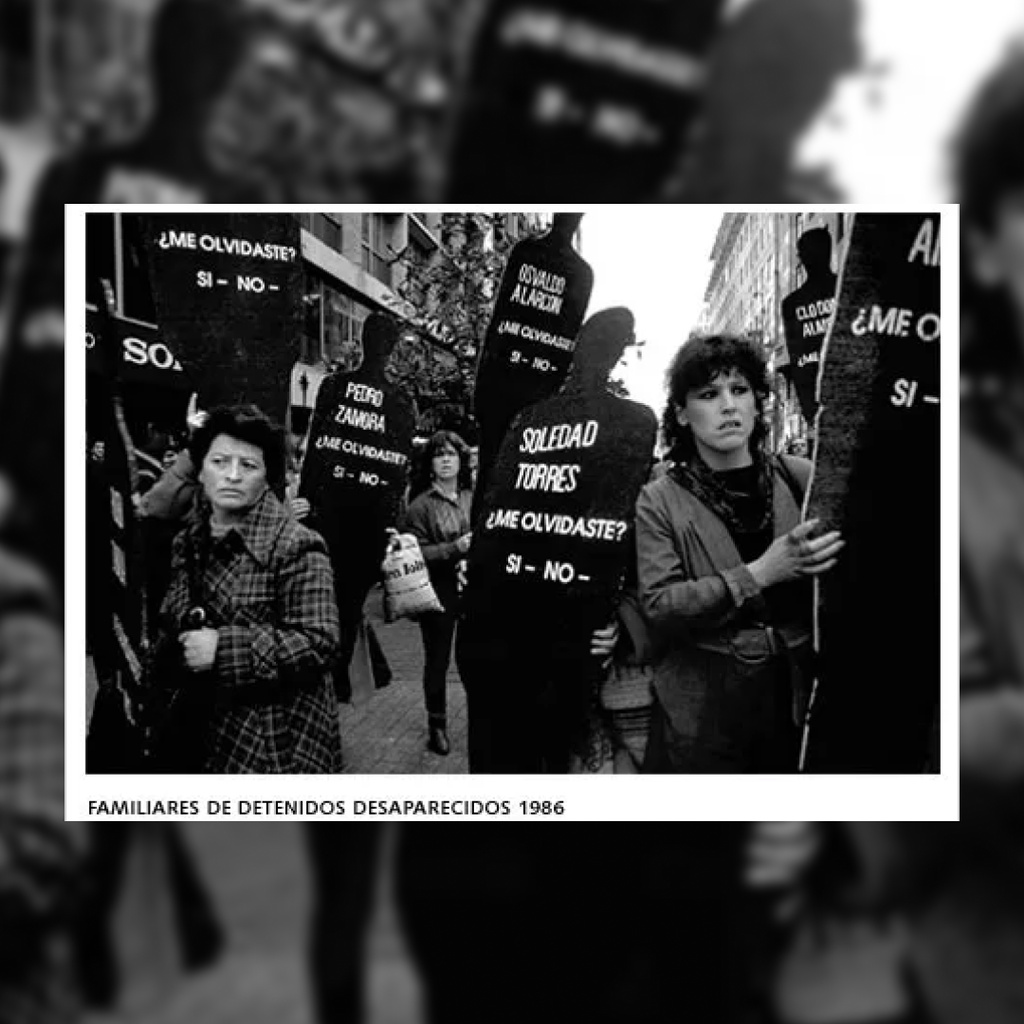

Did you forget me? Yes or No

Who asks me this question? A dead person? All dead people? I will pretend that you are asking me, and I will answer: I could not forget you because I did not know you. My grandmother, your mother, told me about you with great difficulty because it made her very sad. In her stories, you were a prince, the most beautiful, the kindest, the smartest, the best son she could have had. But not a fairy tale prince, a prince swallowed alive and stewing in a monster’s guts, a horror story prince. Then my grandmother would shut up, lest she burst into tears. It wasn’t easy for my mother either. She tried to keep the stories from being so bitter, but knowing the outcome was impossible. They camped on deserted beaches, got married and had a daughter. Over the years, I’ve come to understand that they didn’t know each other that well. There was love, intensity, dreams of a future for the family and for the homeland, all destroyed, but there was no time.

He was dead at twenty-six, and she was a widow at twenty-four. The stories of your brothers and sisters, your friends, your grandmother and father, the women who loved you, your fellow Party members and those who shared a cell with you were also tales of horror and heroism. It is sad that I cannot think of you otherwise. Many times, in the midst of insomnia, when unrelated fragments of these stories come back to me, I would like to think of something else, to distract myself, to forget once and for all the historical tragedy and human wickedness that destroyed your destiny. But I cannot. By now, it is engraved in my cellular tissue; it is part of my body. Besides, it feels very real, the duty to keep telling the children these stories that always end in Never Again. Only sometimes do I manage to think of you with unfeeling tenderness. I manage to pull the imagined horrible grimace out of the still smile of your photos and say to your spirit things like: “Listen, a chucao, the engine of a motorboat, a sea wolf.”

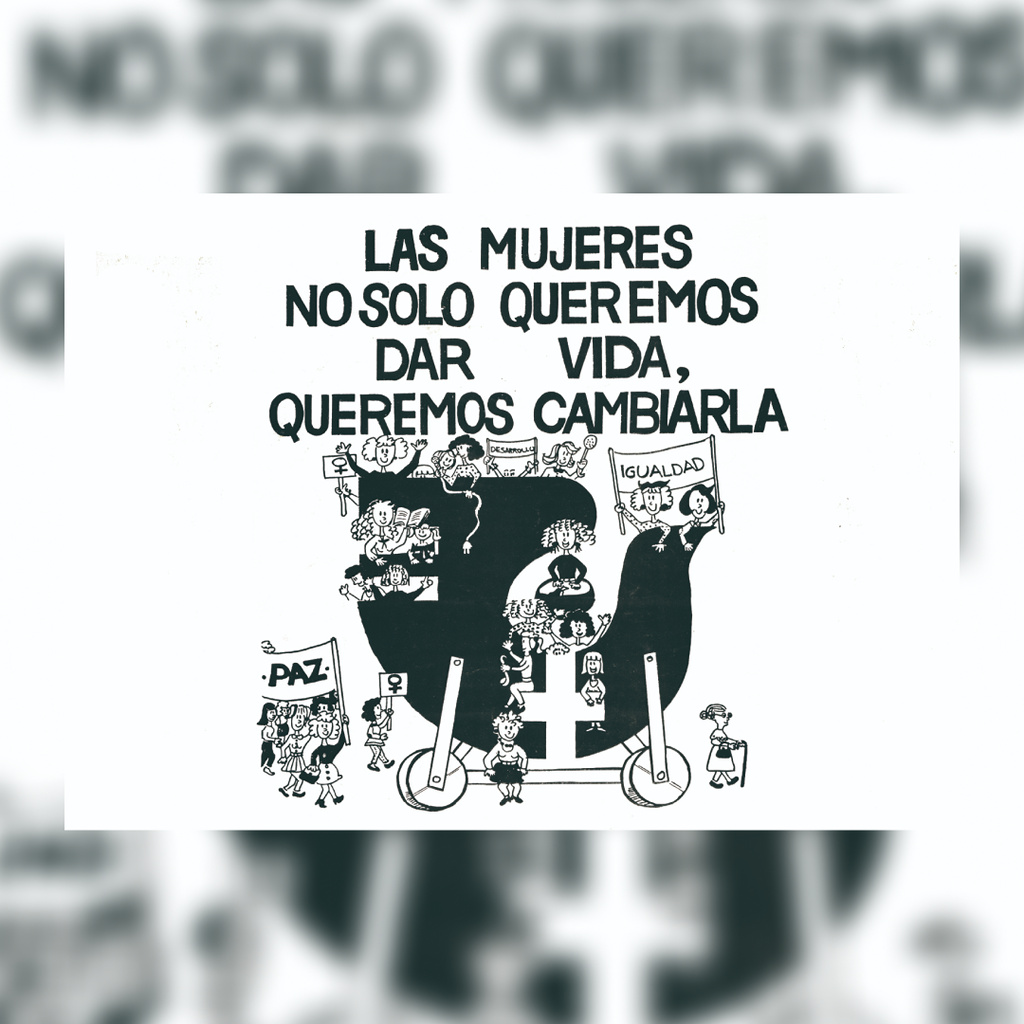

The woman gives life, dictatorship exterminates

In Chile, like in the rest of the world, we can distinguish different waves of feminism, which are closely related to the historical context of which they are part. Thus, if the first feminist wave was characterized by uniting the voices of different women who demanded women’s suffrage; the second wave was marked by the context of the civil-military dictatorship and opposition movements to it, mainly denouncing violations of human rights.

Through pamphlets and public participation, women’s groups raised their voices against the atrocities suffered in the country. Since the media was favorable to the regime and did not cover the reality, the streets became the space to spread the demands, which were not only restricted to the return to democracy, but also to the transformation of the social role of women. With this, slogans such as “Democracy in the country and in bed” or “Woman gives life, the dictatorship exterminates it” emerged, in which the importance of Democracy was expressed to advance the questioning of gender roles, and at the same time, the participation of women to ensure democracy.

In this process, the work of women such as Julieta Kirkwood, a sociologist and political scientist at the University of Chile, became relevant, questioning the role of women in the public space and defending the idea that without feminism there is no democracy. Affirming there should be spaces for female participation in politics, to ensure social transformation. Although this was evident during the 80s, it is a vision that could be extrapolated to today, where gender roles and women’s participation in politics continue to be questioned.

Lotty Does a Mile of Crosses

Without a doubt, this well-known, poignant work leads us towards a crucial state of affairs, through rocky and swampy terrain, like the difficulty of navigating towards a future or simply the celebration of an encounter.

“A mile of crosses on the pavement” by the groundbreaking artist Lotty Rosenfeld invites us to rethink simplifying an image and problematizing action through gesture and concept. It delves into diverse languages and meanings that not only fulfil the purpose of giving orientation and importance to indirect communication, but also raise awareness through a situated intervention that gives space to political initiative or movement.

It is a tangle composed of resemblances or similarities that seeks both to sensitize and provoke, perhaps wanting to sustain an impression, by removing sediments that had hardened the spirit. It presents public action as viable, manifesting, like the threads that cross in this tapestry, a pattern that tries to craft a lamentable image of reality.

It alludes to a permanent chain of oppressive intersections that offer nothing more than the challenge to jump over traffic control lines. That is, to face or dodge the conditions that establish an autocratic and tyrannical route, one willing to align and reduce, shatter and disappear.

These are the constraints that crossed and remain in Chile due to the civil-military dictatorship during the 70s and 80s, wherein intense, particular artistic experiences were developed, linked to interventions particularly revealing within a traditional art scene. In this case, the work’s artist was surely driven to provoke and at the same time stimulate thought and awareness, as does this tapestry, which functions as a mediation of Lotty’s work, making us realize the power of particular means of action as a source of knowledge for sheltering open and collective reflection. Building on this while involving other tools, materials, and processes, the weavers approach the work in question as a textile in dialogue, converting its production into a place of care and memory, simply by crafting it and innovating via authentic designs that describe and call attention so as not to forget.

Illegal adoptions

The silences of forced adoption. Mothers and children who are looking for each other.

Giving birth may be one of the most beautiful and difficult acts that women experience. We are flooded with feelings of immense responsibility that may overwhelm us. That is why we try to inscribe every detail of that moment in memory, suspending time whenever we remember this bond with our children. Imagine that after that moment, your child is taken by a public official, a volunteer, a religious person, a social worker, etc. Imagine that your child is given up for dead. Imagine that on your way to work, you leave your child at daycare, and when you return, they tell you that your child was given up for adoption to a foreigner. Imagine that all your life you have asked yourself: Where is my child? Imagine that you are that child and that you are looking for your biological origins in Chile. Imagine a country where this reality affects thousands of families.

Forced adoptions of children, involving state agents and public officials, largely took place during the civil-military dictatorship in Chile. In this context, a mother-child policy was developed that sought to significantly increase the number of adoptions of poor children, with the aim of reducing what the regime considered a “fiscal burden.” To achieve this, they mainly developed mechanisms to disqualify families, especially young mothers, from raising their children, through falsified records and judicial procedures that operated without any consent from families.

Since 2014, the Group “Children and Mothers of Silence” (Hijos y Madres del Silencio, HMS) has been working to accompany the searches for those affected, developing actions to make the problem visible and promoting national awareness about forced adoptions. The tapestry that refers to this topic is a reinterpretation of the HMS Group logo, which seeks to represent the moment when the children were separated from their mothers, rather than the actions that this valuable group has carried out in the search for truth and justice to achieve the reunion between children mercilessly stolen and their families.

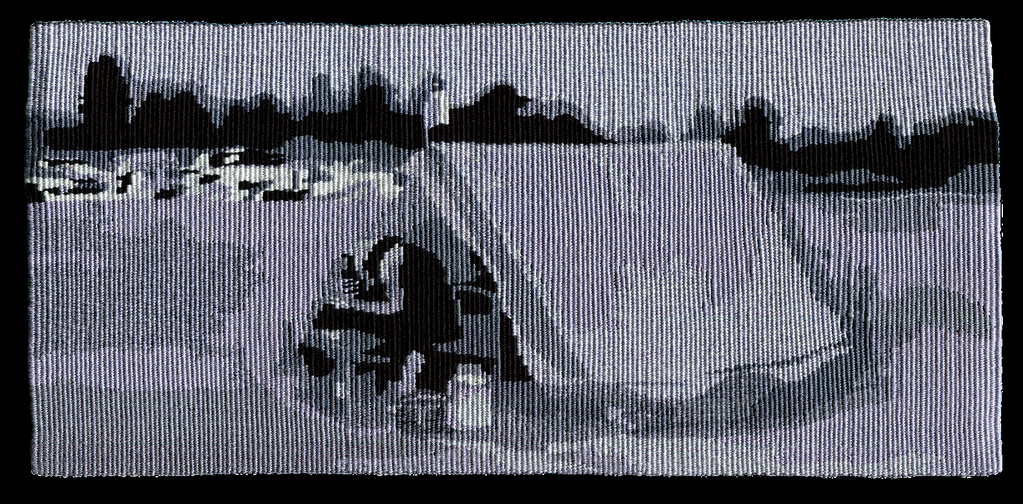

Searching in the desert

I am sending you this letter, to heaven, to eternity, to wherever you are. This desert is just a way station. Words travel, right? I don’t want to send this letter to the abyss of the desert. My words would get lost, they would get confused with the grains of sand… May my words be amplified in the middle of this immense stretch of sand, to finally find you one day and then take you to a garden. I want you to be in a garden, where the shade of the trees can shelter you from this infernal heat. How much does a grain of sand weigh? It’s so small, look. It weighs nothing. Do you see? I am small again today, like that day when horror broke out. Suddenly, they, with their war rifles, pointed at us all. Do you remember? It’s just a saying, of course you remember. And so do I. And then there was the Caravan of Death traveling through Chile.

It is September 1973. In October, it arrived here… How big is a desert? Can it be measured? How big is silence? Can it be measured? I don’t understand. I still can’t understand. They say, one day they said – who, why? – That you are in this desert. How is that possible? Where? My silhouette with this shovel is lost in the immensity of the desert’s image. They don’t see me. They don’t want to see us. I want to scream. They don’t want to listen. You do, I’m sure you do, that’s why I’m talking to you, while I insist on removing this endless sand. We women have organized ourselves to go out into the desert. Today. Yesterday. How many years have we been here? How many? I’m one step away from finding you. In the next excavation, perhaps… Or the next. Or the next. And I can’t do anything other than keep looking for you. Because… what would you do? Where are you? Where? And yes, it may be that when I find some trace of you, you won’t actually be in what I finally find. But I want to take you to a garden, papá. I want the shade of the trees to finally shelter you.

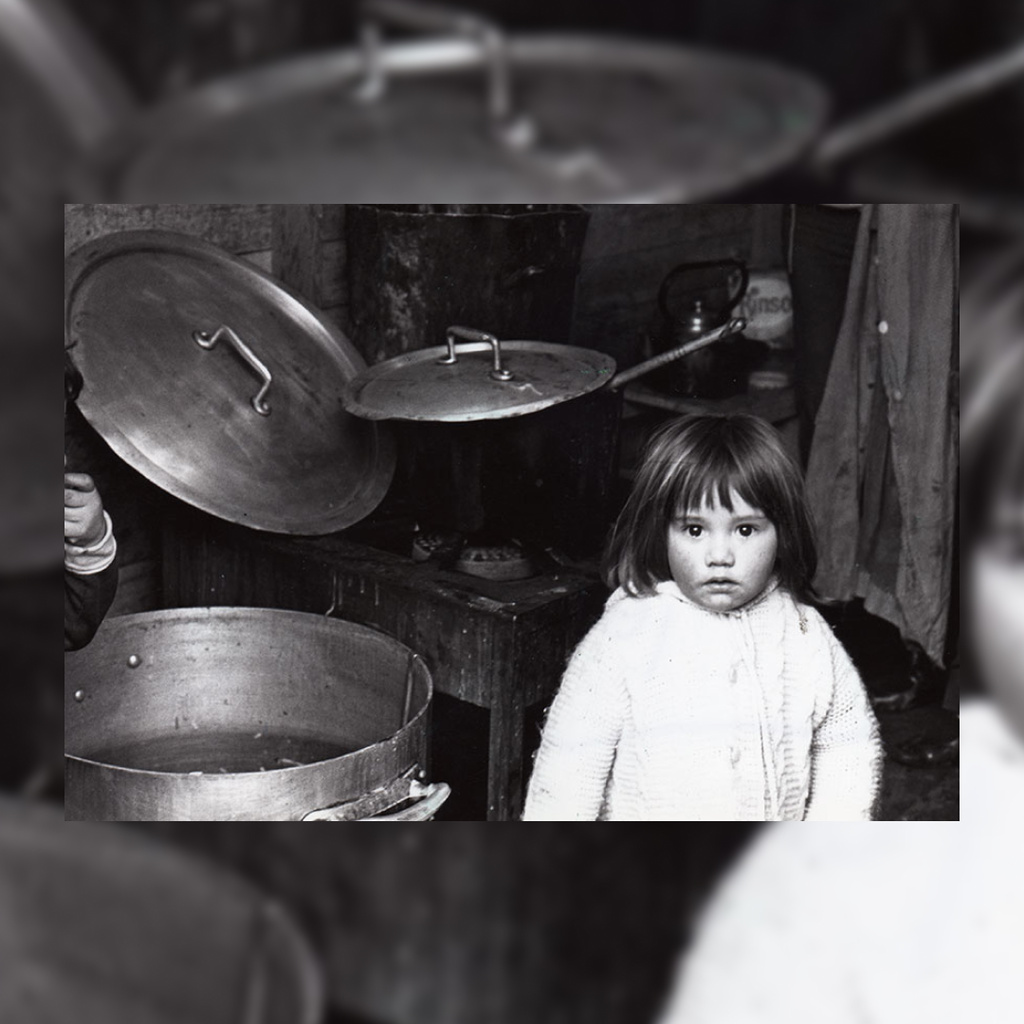

Communal Soup Kitchens

Despite the talk about the economic growth experienced by Chile during the dictatorship, the working class saw several fundamental rights highly violated, including the right to food. While it is true that these groups had historically suffered from neglect in this matter, hunger in the communities increased after 1973. As a result, communal soup kitchens began to proliferate as a way to address poverty. These spaces were present in multiple communities nationwide, offering food prepared by the same women, mothers, and girls who participated in the work. Women emerged here as driving forces to tackle the problems of scarcity and subsistence, and it is important, in that sense, to recognize their high value and political action.

Communal pots, as generators of residual spaces of citizenship, were one of the most common forms of organization to solve the problem of subsistence in times of dictatorship. Women were not only responsible for cooking food but also for collecting, managing, and distributing it. Being aware of the needs of the working-class, their daily work allowed these cooks to observe the economic and political reality of their environment from within. Between 1982 and 1986, the number of organizations of this type tripled, and it is estimated that by 1986 there were a total of 1,383 subsistence entities. Among these, those associated with consumption, especially food, stood out, with communal pots being the most massive.

Working-class women had extensive political participation in the context of the dictatorship. They were the ones who organized around subsistence, a non-negligible aspect considering that it allowed the working-class to address the problems of hunger and family deprivation.

Round Play in a Protest

- La Ronda (Women´s round dances) The photographic images of Paz Errázuriz, on International Women’s Day (March 8), B/W photography, 1985.

Close-ups and framing have become central elements in the grand narrative of visual studies and photography. Not only do they highlight portions of reality. In this case, photographer Paz Errázuriz wanted to bring to the eye a demonstration for International Women’s Day in 1985. But there are also a series of disquisitions on the details of each image: what is included, what is strictly visible, and the representation of a point of view. And, of course, in a spectral way, that which does not fit into the photograph, that which is radically contingent and takes place outside the visual event. Photography became a key tool for denouncing crimes against humanity, but also a valuable prism for leaving traces of a militant memory as an alternative to that imposed by the military regime. In 1981, a group of photographers decided to form an association and, camera in hand, to go out to confront life where the images were taken. In this space, the photographic practice was established as part of a series of flashes of truth in a society submerged in prohibitions, disappearances and censorship.

Several women participated in these acts of visibility, and they were also the ones who managed to break the strict patriarchal margins and contribute their views to the construction of a political horizon for the photographs, far from any historical particularity. Errázuriz’s “Ronda” is an expression of the many “rondas” that have emerged from different places in the capital up to the present day. I can’t help but think of the photographic archives of Kena Lorenzini and her women’s “rondas” at the intersection of the streets Cumming and Alameda, or the “rondas” of Mariela Rivera in front of La Moneda during democracy. A kind of intertwining of hands and jumps, movements that at times seem to make them float between laughter and shouts. Small symbolic occupations in public space, where solidarity and mutual care are experienced, accompanied by the photographic gesture in which the photojournalists were involved.

La Ballena Beach

Chilean landscapes have a temporality that is difficult to assimilate from the brief human existence, but they are much more than simple geographies. They are witnesses of the history of the people who lived in them, loved in them, and suffered in them; and their disappearance. Playa La Ballena, in La Ligua, is one of these places. Now consecrated as a site of memory, its waters hold the testimony of the people detained and cast into the sea by the civil-military dictatorship. They are also a brutal reminder of the repression towards women at the time, who not only faced persecution for their opposition to the dictatorship, but also for their mere existence.

During this dark period in our history, an attempt was made to reaffirm the traditional conception of women, associating them with the private space. Those who participated in the public sphere were considered enemies. 3,621 tortured women and nearly 3,400 victims of sexual abuse document the suffering of these brave fighters for human rights and democracy. Playa La Ballena, and its waters, brought to light the truth about Marta Lidia Ugarte Román, a member of the Communist Party, teacher, dressmaker and member of the party’s central committee. Her body was thrown into the sea after her arrest in Villa Grimaldi in 1976, a crime that was tried to be covered up as a “crime of passion” by the authorities. This discovery revealed many other people who were made to disappear by the authorities in the sea, the desert and the mountains.

Our landscapes are not only natural wonders, but also reminders of the absence and suffering of people still seeking justice and truth. Although human memory is fragile, the memory of space persists, preserving the truth denied to the families of the disappeared detainees.

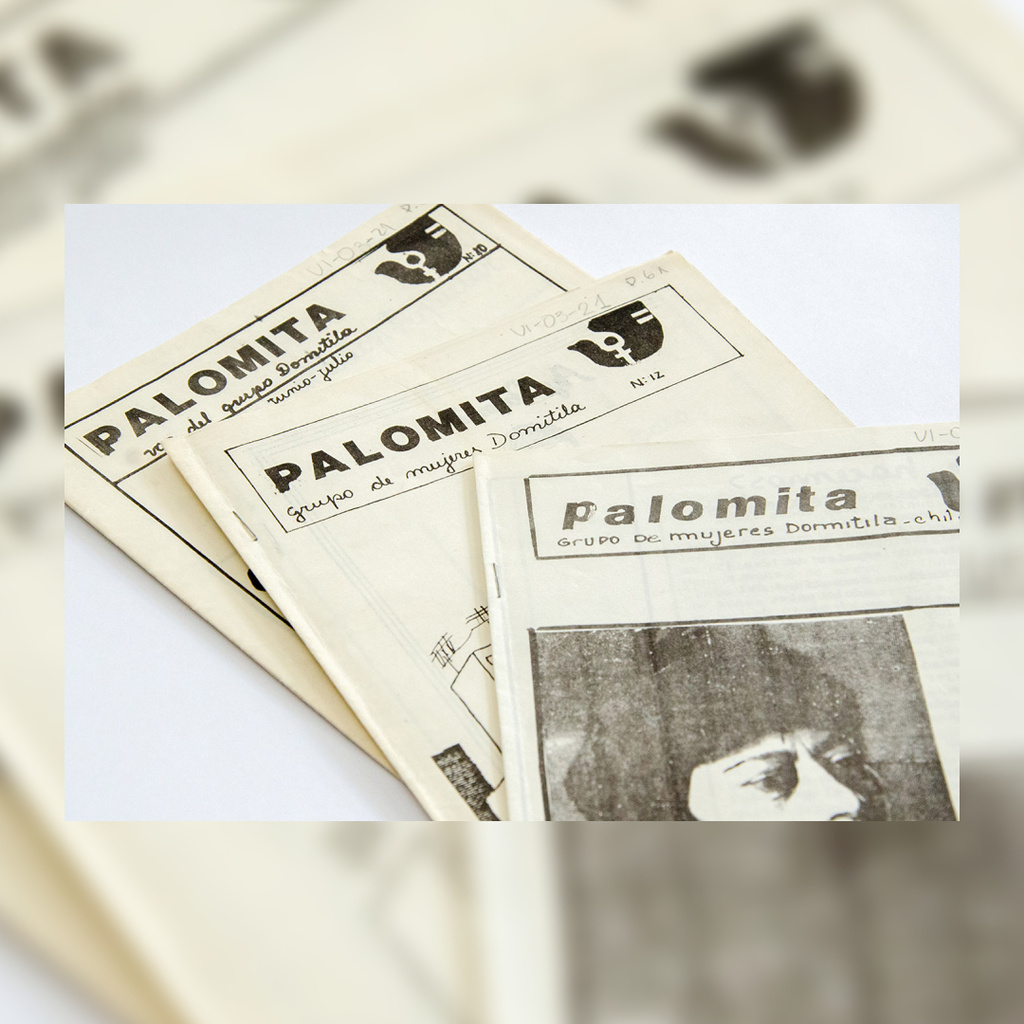

Newsletter Palomita

The Palomita newsletter logo connects us with the history of feminist internationalism. It is the logo of the United Nations Decade for Women (1975-1985), which was established thanks to the impulse of the powerful world-wide feminist movement of the 60s and 70s, and which in turn meant an important milestone in the legitimization of feminism in the institutions of international politics. In Santiago de Chile, a group of women pobladoras (urban dwellers) who called themselves “las Domitilas” (recovering the name of the Bolivian indigenous fighter Domitila Barrios de Chungara) appropriated this logo and used it in Palomita, which they published periodically between 1985 and 1988 to share their views and struggles.

Palomita was one of the various magazines and boletinas (newsletters) with which leftist women’s organizations, pobladoras (urban dwellers), feminists and intellectuals circulated their reflections on the politics of the country and their homes, opening a debate that we continue to sustain and weave today. The complete issues of the digitized magazines can be read at https://boletinasfeministas.org/

Woman with Pearls Protesting

Some words are difficult. Perhaps because we don’t really know what they mean, or, on the contrary, because we know exactly what they mean. Something similar is true for Resistencia. Resisting, as a political category, has a very delimited conceptual framework: from Gramsci onwards, resistance has been seen by social sciences as the possibilities of subaltern groups to dispute political, cultural and economic hegemony, among other ones. Its use, mainly in the sixties, seventies and eighties in Latin America, was also tantamount to “just violence” (Hinner, 2015), and, in the collective imagination, it acknowledges one particular figure: the militant-man. In the last thirty years, research in this subject—led mainly by women—has complemented the classic figure associated with resistance with that of the militant-woman (Troncoso, 2020) and the link between historical memory and gender. Thus, from feminisms it has been possible to weave the stories of resistances from situated analytical frameworks that recognize life stories, minuscule stories, solidarities and affections as spaces of resistance to the civil-military dictatorship in Chile.

The two images that elicit this collective dialogue invite me precisely to do just that: to decompose the representation of resistance in Dictatorship, in order to imagine resistant bodies with hoods and beads. Shouting and in silence. Skirts and pants. With purses and backpacks. And deterritorialize their emergency to reflect on vivid resistances, past and recent, with Chilean, Mapuche and gender-based dissident flags, and to think of resistance as an embodiment of a political-ethical act.

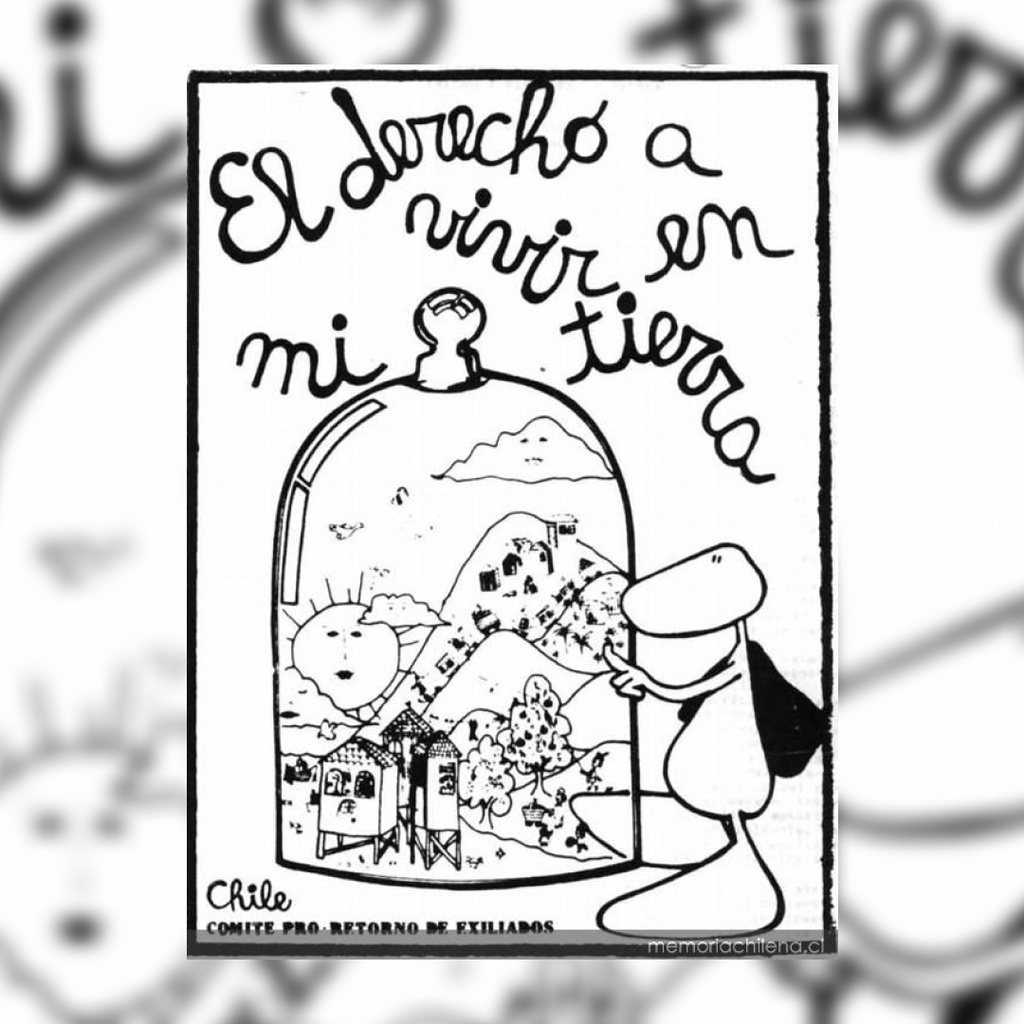

The right to live in my country

ExileI had a childhood with many stopovers, I learned to sleep in airports, to think in one language and speak in another, to have friends instead of cousins, and I learned that happy trips were done by car and sad ones by plane. The first sad trip was in 1974. You had to do everything that way, fast. You had to wake up, pack your bags, close the doors and windows, go to the airport…

In those years, the airport of Santiago looked like a bus terminal in a desert valley. The sound of the military helicopters flying over the runways was mingled with the sound of the ventilators, through which the air barely passed. The farewells were silent. A glass partition separated those who left from those who stayed. As we passed through the international police, they pulled Mom away from the line and checked to see if she was in order with the new decree. Only one suitcase per family was allowed, and a maximum of $100 could be taken out of the country. They turned Mom’s cosmetics upside down and said they would question her if they found any more U.S. bills.

The inspection was ruthless. The humiliation served as a lesson to others. They asked her, always shouting, because enemies are not spoken to in a low voice, her full name, all four of her last names. They made fun of the fact that one of them was a foreign name. They asked her how old she was. They asked her about her pregnant belly, her destination, and maybe something else: Rome, she said, “Say hello to the Pope,” they said, “Vacation,” “No,” “Family visit,” “No,” “Religious tourism,” “No,” “Religious tourism,” “No,” “No.” Her silence gave the man who was questioning her some clues. No, the trip was not for tourism or adventure, nor was it for work or study, much less for pleasure or entertainment. The journey belonged to the family of other journeys. Unwanted or unplanned trips, trips made by accident or force majeure, forced trips with only one ticket, one way and no return; trips officially known as migrations, exoduses, escapes or deportations. Journeys with a tattooed letter, the L. Journeys that are clearly not to be photographed, but that leave photographic traces.

Demonstration for Women’s Rights in the Caupolican Theatre

On December 29, 1983, thousands of women woke up very early in Santiago, quite anxious and alert. We had an urgent historic commitment to carry out.

It was the Chile of the Dictatorship, of repression, silencing, persecution, exile and death. Thousands of women would meet at the Caupolicán Theater to express our vital decision to fight together to change the horrible situation we were living through in our beloved country and to call on Chileans to combine forces for this historic commitment to change.

We arrived fearfully, in small groups. The Caupolicán was surrounded by sinister and repressive troops, but there were more and more of us who crossed those cordons and entered the premises. Inside, we hugged each other and smiled. The call began: we applauded, shouted, sang and laughed. And we all committed ourselves to this historic demand. TODAY AND NOT TOMORROW, FOR LIFE. We left full of hope, joy and strength. The strength that gave us unity accompanied us for many years in thousands of actions and demonstrations throughout the country until we defeated the dictatorship and recovered democracy in our nation.

Land Occupations

In the plots of memory, the legacy of a dark time under the dictatorship, a time of vital precariousness, dehumanization and oppression that deeply marked the country. In this story, women emerge as the beating heart of the city, shaping its form and identity, although their contribution has often been invisible in conventional narratives. An essential part of Latin American cities have been built informally, being the land occupations acts of resistance and survival that have become constitutive elements of a formal city. In each occupation, in each reclaimed space, women’s movements have written their history, starting from the struggle of family subsistence to the construction of communities and neighborhoods that today shape our city and society. This integration of the material and the social needs represents not only an act of physical resistance, but also a profound statement of existence, a bold redefinition of the urban and socio-political landscape. The community, based on its accumulated needs and experiences, has occupied and constructed its own habitat.

The women, aware of the vulnerabilities exacerbated by the dictatorship, have led the self-construction and the strengthening of the community, weaving collective strategies that have become fundamental in daily life and the vision of the future of their population. This commitment anchors social life in producing urban space, fusing the intimate and the collective. Women have simultaneously made private and everyday life emerge as a political and public act. Despite the adversities imposed by the dictatorship, women have been pillars in the reconstruction and imagination of urban space. In our struggle, the city is transformed, becoming a testimony of hope, memory, and perseverance, reminding us at every step of the importance of recognizing and valuing the central role that women play in shaping shared space. This is what we see today in the movements of struggle for housing and the right to the city, which continue to be fundamentally feminine.

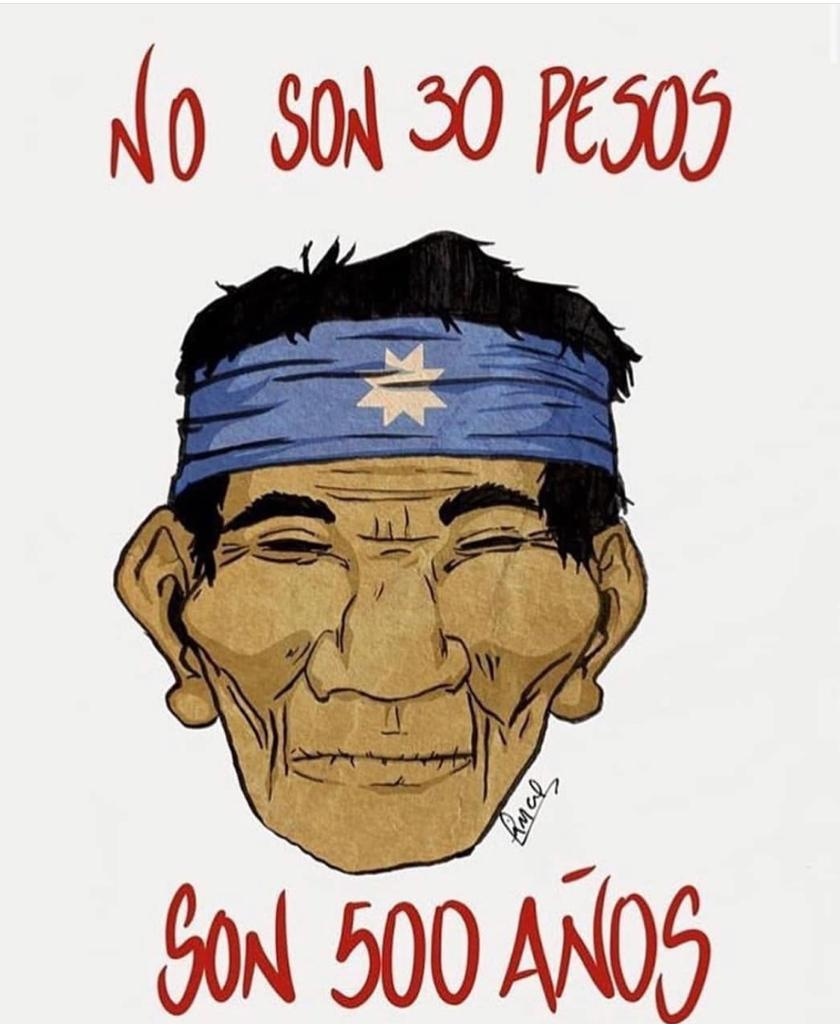

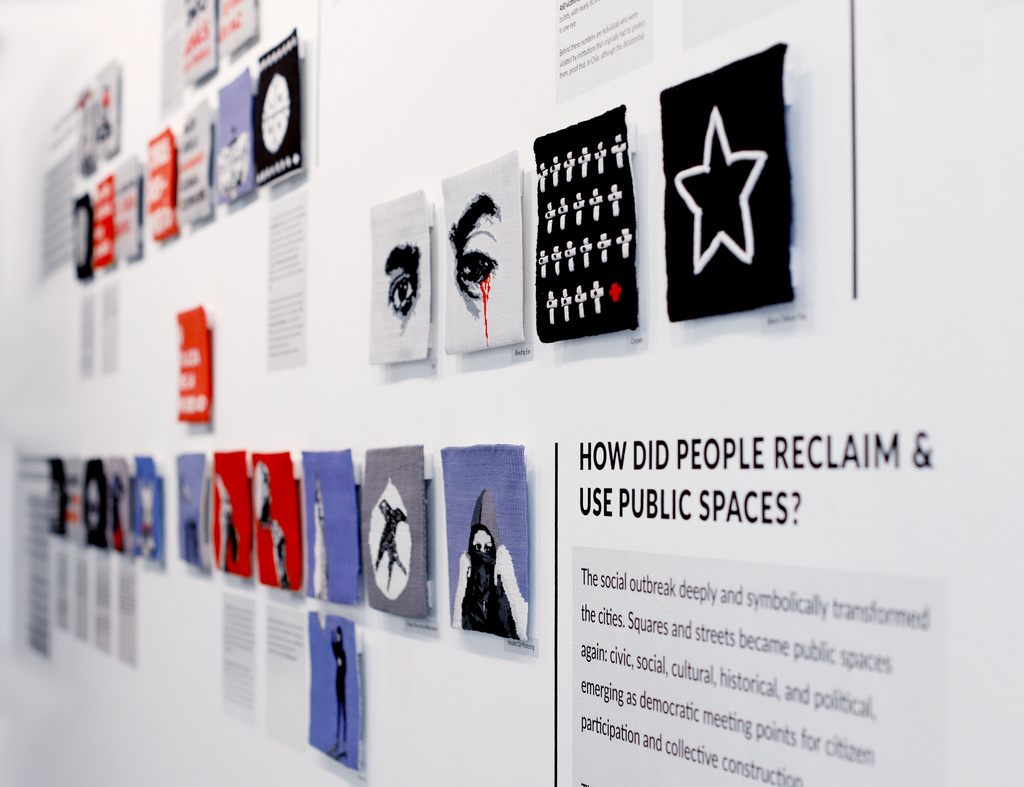

CHRONICLE OF A SOCIAL REVOLT

In 2019, during the historical social revolt, a group of women weavers united to create a collective tapestry that reflected our experiences. This piece allowed us to explore how to reconstruct the social fabric and develop a living portrayal of the events. Now, five years later, we are trying to make sense of the uprising and reflect on its significance by mixing words with textile art.

Context

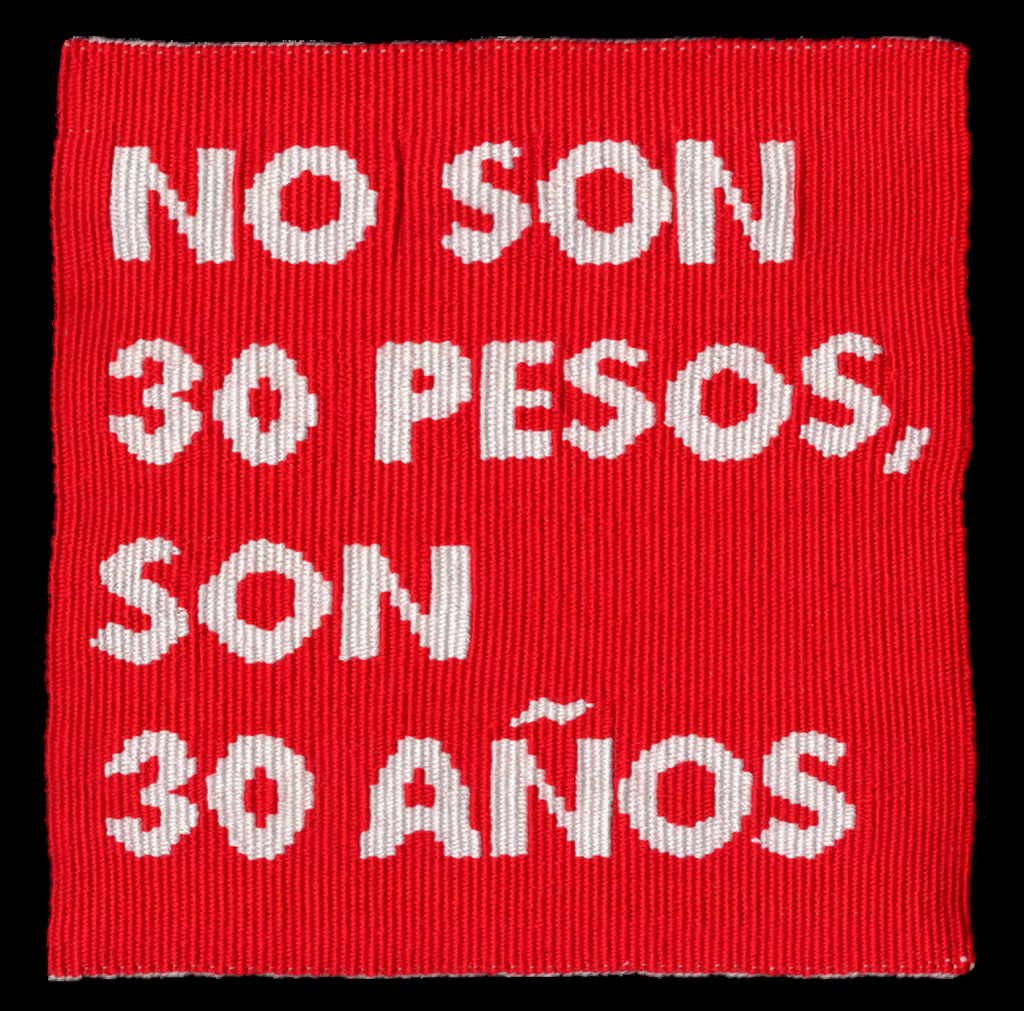

On October 18th, 2019, Chilean students began protesting against a $30 pesos (3.8 cents of a dollar) increase in public transportation fares; they proclaimed that it was not just $30 but 30 years of post-dictatorship governments that had failed to work for social justice.

This historical process, which is called Social Revolt, reflects the uprising of a significant part of the population that originates from discontent and rebellion against the power structure and politics. It emphasizes the idea that the causes of discontent have been accumulated over a long period of time, stressing the need for structural change.

In this way, in the streets, you could hear: Chile woke up from its neoliberal dream. From the rhetoric of the nation-state. From the antidepressant to combat the individual crisis.

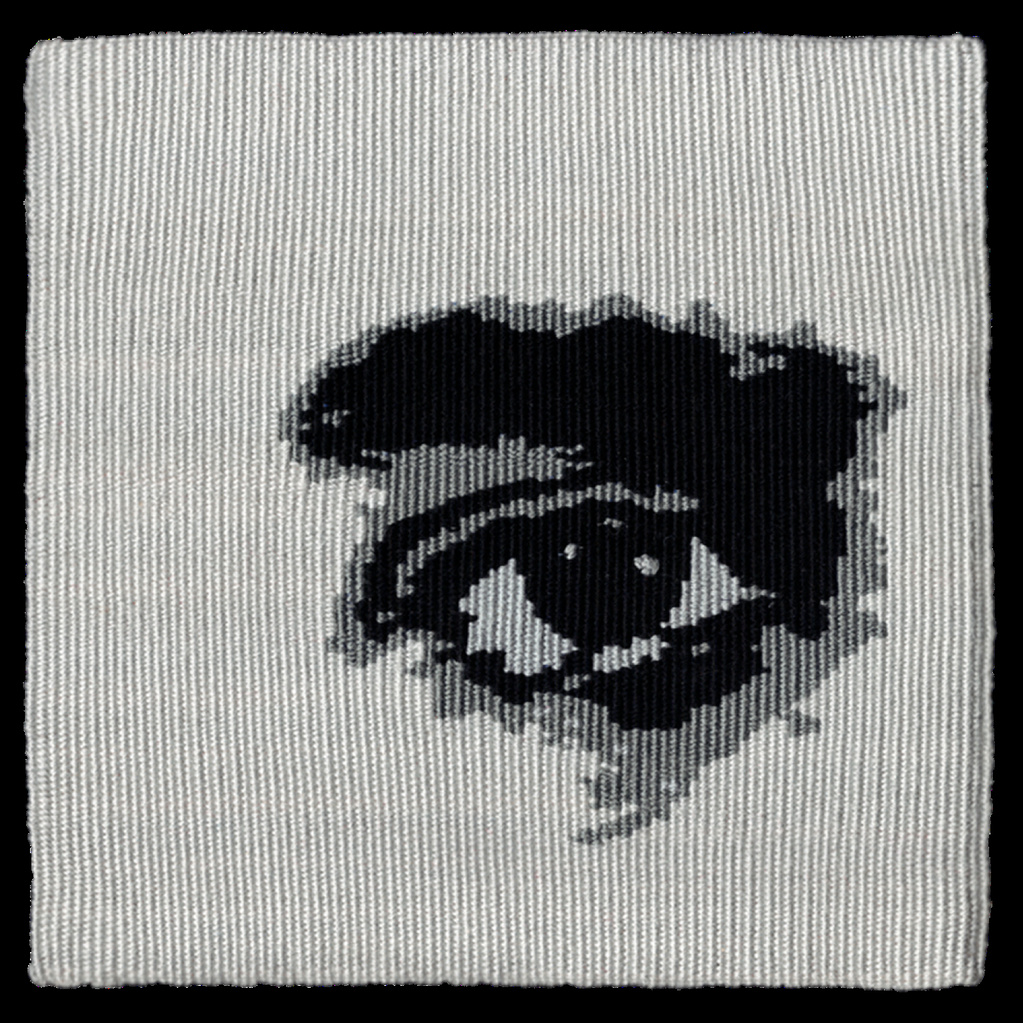

Violence and Human Rights

At some point, as a society, we had to agree on establishing a minimum standard of humanity, leading to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. These rights were enshrined in Chile’s current constitution, written in 1980 in a context of dictatorship and violations of those same rights.

The Dictatorship was largely based on the logic of terror and in putting effort to dismantle social movements, shaping an individualistic society where people tended to isolate themselves out of fear of being denounced. From this emerged fears like openly discussing politics or protesting.

Numbers show that between October 2019 and March 2020, 3,777 victims filed lawsuits for unlawful coercion, torture, unnecessary violence, and other forms of abuse. At least 20% of the victims reported sexual violence, speaking to the double punishment, not only for protesting but also for being women. But one of the most alarming figures relates to the 460 victims of ocular trauma, mainly caused by rubber bullets, with nearly 80% of these individuals left blind in one eye.

Behind these numbers are individuals who were violated by institutions that originally had to protect them, proof that, in Chile, although the dictatorship feels more distant with time, it installed a way of viewing the forces of order as enemies to the people. Thus, whenever people express their discontent over injustice, that old fear of the “internal enemy” resurfaces, one who seeks to destroy everything we know and bring chaos. The fact that there is a need to establish a minimum standard of humanity and safeguards on how state institutions exercise power shows that the peace we believe we live in is a fragile fiction hanging by a thread.

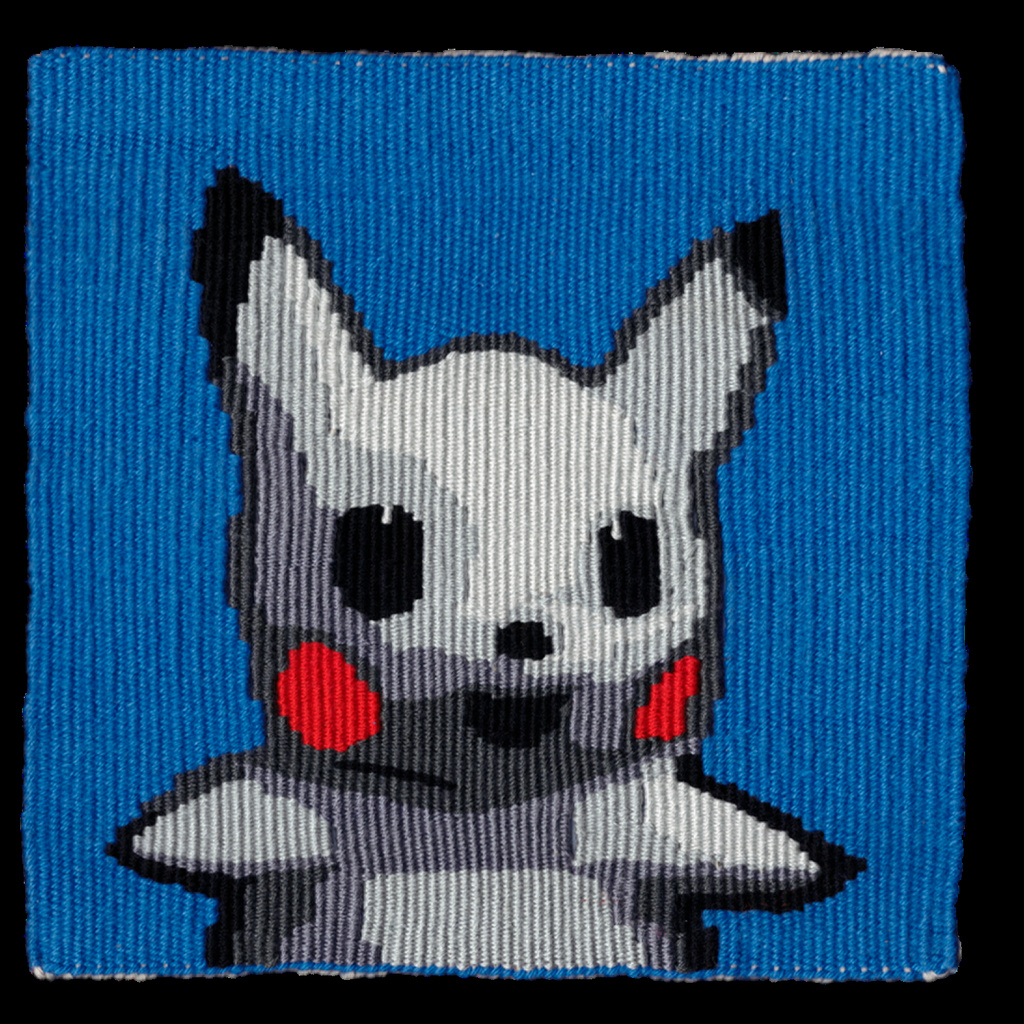

Social Revolt and Pop Culture

The demonstrations and protests came over, everything, everywhere and all at once. On October 19th, the president imposed a state of siege and, a day after, declared that we were “at war against a powerful, relentless enemy”. On the same October 20th, a personal WhatsApp audio of the first woman, Cecilia Morel, leaked and went viral: “Friend (…) This is coming is very, very serious (…) it’s like a foreign invasion, aliens, I don’t know how to say it, and we don’t have the tools to combat it (…) we’re going to have to diminish our privileges and share with others. ” Amidst all this, the image of a black mutt with a red bandana on its neck became widely known. It was the “negro matapacos,” a stray dog, revisited from the popular collective memory of the 2011 student manifestations when this dog used to participate in the confrontation between youth and police and their guanacos.

The figure of Pikachu (a Pokémon creature) emerged spontaneously during the demonstrations. Someone dressed in this character’s costume made their way through the crowd. From then on, Pikachu was a constant presence. It appeared on banners, and, like a magical act, the costume could simultaneously be seen in different places. While the figure of the alien was a satirical answer to the government’s statements and Negro Matapacos represented the struggle of the people, Pikachu had transformed into a collective symbol of pop culture in Chile’s October.

Chants

There were more than 450 victims of ocular trauma in Chile during the protests.

When, from October 18th, the cry “CHILE HAS WOKEN UP” began to be heard in the streets. The cruel and senseless paradox is that this slogan was raised practically at the same time as the repression shot precisely at those eyes.

Between State violence, social mobilizations expanded even further. Everything that had been understood as sectoral demands made sense in a struggle “UNTIL DIGNITY BECOMES CUSTOM”: Dignity was thus the awakening of the individual dream to build collectively, with open eyes. The dictatorship and its subsequent transition had taken away dignity as a form of social relationship. And if the dictatorship was the one who took away dignity, its most perfect instrument had to be overthrown: the Constitution. “NEW CONSTITUTION OR NOTHING” was written in the streets while town councils were self-organized. A Constitution had to be written where the dignity of the people was the ink—of the people, of all the people.

Social Revolt and Music

A polyphony is a musical texture where two or more independent melodic lines are heard simultaneously. During the social revolt of October, different voices, colors, and melodies echoed through the streets. It wasn’t a carnival like the ones the nineteenth-century aristocracy decided to remove from the calendar to promote popular culture. No. It was the music that accompanied the awakening. It was the sound of the reconnection that the neoliberal illusion had created: our problems and demands were not individual; our social experience was not personal. People’s historical memory is transmitted through words, emotions, and the body. That’s why no one was surprised that the songs accompanying the social polyphony of the Chilean uprising were precisely songs of memory—or songs with memory.

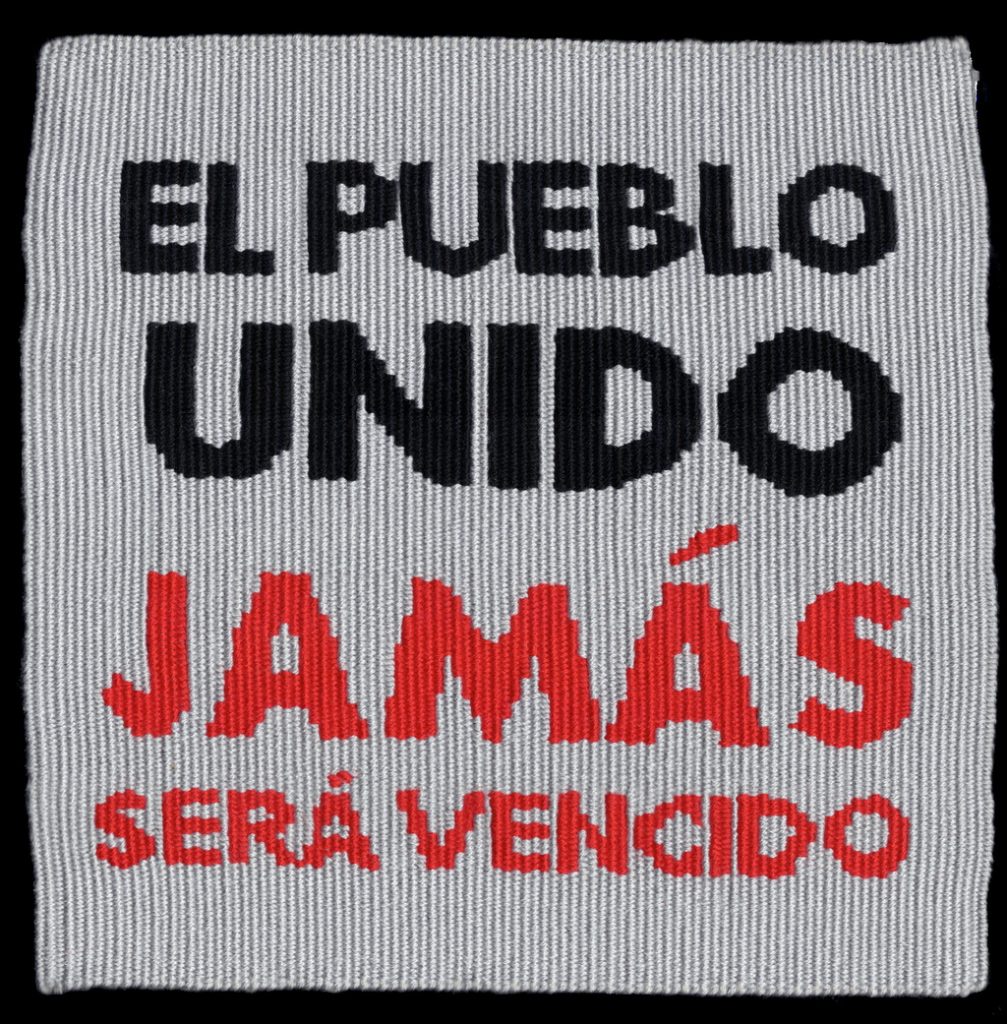

For example, “The people united will never be defeated” was sung during Salvador Allende’s presidential campaign in 1970 when the people sought to weave a shared life project through the State with their hands. The military coup that overthrew Salvador Allende’s government and the immediate State terrorism imposed for eighteen years in Chile symbolized much of its monstrosity in the detention, torture, and murder of singer-songwriter Víctor Jara. He was a singer-songwriter of the process that had brought Salvador Allende to power and whose lyrics mobilized past and present struggles. When State agents’ repression began to be unleashed against the people who protested in October 2019, the people once again sang the song Víctor Jara had composed to protest against the bloody U.S. intervention in the Vietnam War: The Right to Live in Peace. We had the right to live. And we had the right to live in peace.

Criminalization and media

Just two days before October 18th, the then-president of Metro, Clemente Pérez, was interviewed on the TV channel 24 Horas to speak about the protests already happening in the subway, each increasing in magnitude. By that time, nearly a thousand people had evaded the payment of tickets. “Kids, this didn’t catch on. You are not braver; you haven’t earned people’s support, not even on Twitter (…) People are concerned about other things; the Chileans are way more civilized”, he said.

Beyond the fact that the diagnosis was proved wrong in a few hours, the interview showed the editorial guidance of the complete news ecosystem: to privilege the voices of those who were against the protests or those who minimized them, denied their legitimacy, or straightly criminalized them.

The bias was so obvious and persistent, shown to an audience that was becoming more critical and empowered, that even the same protests started targeting the media: citizens walked to the TV channels while they were transmitting live to ask them to speak the truth. Although this strongly opened a discussion about ethics in the media, no concrete action was taken to guarantee impartiality and commitment to the truth in the news ecosystem.

Use of Public Space

Plaza Italia has oscillated between being a point of convergence and a line of demarcation, from the vertex that gave rise to the city’s central space to the space that divides and juxtaposes realities and perceptions. This duality has determined its character as a vibrant stage of collective expression, where festivities and victories are celebrated, voices of discontent are raised, and social and artistic causes are vindicated.

The social revolt radically transformed the use and meaning of this central place in the capital. In those turbulent days, the public space became a battleground, where mass protests and clashes with security forces spread throughout the city center.

The revolt not only altered the configuration of the urban and social environment but also infiltrated the soundscape and visual landscape of the space, transforming it into a vibrant canvas of resistance and reclamation, renaming it “Dignity Square.”

The graphic expressions that adorned its walls not only made visible the demands of the social movement but also reinvented the aesthetics and character of the place, profoundly transforming the visual landscape of the historic center. The facades and walls became palpable testimonies of the struggle, questioning passersby and authorities and marking a critical presence. In reappropriating a public space through images, a reclaiming gesture became visible.

- Soil Gallery, Seattle – Exhibition dates: November 7 to November 30, 2024

- Soil Gallery, Seattle – Exhibition dates: November 7 to November 30, 2024

- Soil Gallery, Seattle – Exhibition dates: November 7 to November 30, 2024

Interweaving the Archive curated by Belén Gallardo (Chile), Daniela Contreras (Chile), and Genevieve Tremblay (USA). Soil Gallery 7-30 November 2024

About Colectiva Tramando

The Colectiva Tramando (Spanish: tramar– to plot/ to weave) was founded in 2019. Our intention as a collective of weavers is to emphasize tapestry – the ancestral practice of the andine mountains – as a means of denunciation, memory and political action. Following the tradition of arpilleristas (lit. burlap, trad. Chilean patchwork art) and embroideresses, we are using the tapestry as a platform of communication and expression to highlight its political role in Contemporary Art. We develop investigative projects of interdisciplinary creation that problematise violations of human rights in Chile ̧ applying a feminist and collaborative focus.

TEAM

Daniela Contreras Flores | Director

Belén Gallardo Quintanilla | Producer

Daniela Rossi Charnes | Production assistant

Mariana Gaete Venegas | Installation and Conservation

Claudia Moreno Arancibia | Design

Alice Jallois Mora | Design

Weavers

Ada Simón

Ady González

Alexis Jara

Arlene Villarroel

Beatriz Leiva

Camila Escobar

Carla Contreras

Chikiza

Constanza Guerrero

Constanza Inostroza

Deysi Cruz

Elizabeth Mejias

Eloisa Pino

Javiera Montenegro

Judit Lara

Leonor Morales

Ligia Maestri

Marcela Flores

Matilde Achurra

Mónica Durán

Paola Moreira

Paula Gálvez

Paula Huenchumil

Paulina Leiva

Paz Martínez

Pía Contreras

Rosario Ceballos

Ruby Castillo

Sebastian Guzmán

Valentina López

Vilma Ojeda

Ximena Barría

Writers

Camila Ruz

Carolina Vega

Claudia Deichler

Consuelo Ferrer

Cynthia Shuffer

Daniela Machtig

Daniela Schroder

Eliana Cardoch-Meza

Elizabeth Mejias

Francisca Palma

Josefa Ruiz-Tagle

Joyce Morales

Karen Alfaro

Loreto González

Marcela Parada

María Saa

María Viera-Gallo

Paola Velásquez

Translators

Alice A Nelson

Gabriela Charnes

Soledad Muñoz

Vicente Lane

Pilar Ortíz

Collaborators

Archivo Nacional

Boletinas Feministas

Colectiva Cocuyas

Giant Golden R

Valentin Jadot

Victoria Díaz