Surabhi Sahgal, Kailash- Stairway to Heaven (from my series of rings titled ‘Manthan’, exploring the mythical Churning of The Ocean of Milk), Silver plated copper, 30mm x 30mm x 18mm,

Surabhi Sahgal’s rings reflect mythical symbology embedded in Indian narratives of heavenly pursuits.

I created this textured ring as a material interpretation of Mt. Kailash, a sacred mountain located in what is now the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. Considered as the abode of Shiva, the Hindu God of destruction, Kailash stands as a symbol of divine detachment, the Axis Mundi of the universe.

The ring came about as I drew out wearable relics from my recent readings of the mythical tale of Samudra Manthan. However, as I sit to contemplate and write on its provenance, I realise that its form and feel have been churning in my subconscious for much longer.

Nearly ten years ago. A Shiva temple tucked in the hills of Uttarakhand. I had just graduated from architecture school and was visiting relatives. A winding drive and a laborious trek through rocky terrain and sporadic shrubbery, brass bells swaying with the spring breeze, their clanging announcing our arrival into Shiva’s territory. Around us were familiar symbols of the ascetic god: tridents stuck in the ground, rudraksh bead necklaces, red scarves adorning tree branches, and the smooth, formless Shivling.

- Photos from my trip to a Shiva Temple, 2017

- Photos from my trip to a Shiva Temple, 2017

In the distance, someone pointed to the faint outline of a peak and said, “That’s Kailash Parbat.” I had no plans of becoming an artist back then, let alone making jewellery inspired by mythology. But something settled quietly within me in that moment – a seed waiting to take root.

Kailash Mountain, Image source: https://www.tibettravel.org/kailash-tour/mount-kailash-mysteries-and-secrets.html

Its icy summit touches Swarga or Heaven, and its subterranean crevices dig into Pataal (Hell); the mountain is considered the celestial axis connecting heaven and earth, a symbolic bridge between materiality and spirituality. Though now prohibited, the ascent of Mount Kailash has long been regarded in Hindu mythology as a sacred stairway to heaven. This journey offered the promise of liberation to those who undertook it.

Vices and Virtues

I’ve persistently been intrigued by the fascinating stories of mythological characters scaling Kailash in the hope of attaining moksha—liberation from the cycles of life, death, and rebirth—one in particular, my reading of Jaya, Devdutt Pattanaik’s retelling of the Mahabharata. The concluding chapters of the book describe this spiritual journey, as undertaken by the Pandava brothers and their shared wife Draupadi, after having lived gloriously dharmic lives, albeit consumed by war and loss.

As they ascend the mountain, Yudhishthir, the eldest Pandava brother, watches his companions fall away one by one. Each fall, Pattanaik explains, is a reflection of the unresolved flaws they carried from their worldly lives—insecurity, gluttony, smugness, insensitivity, and partiality. Only Yudhishthir, unwavering in his dharmic responsibilities and moral clarity, continues up to the summit.

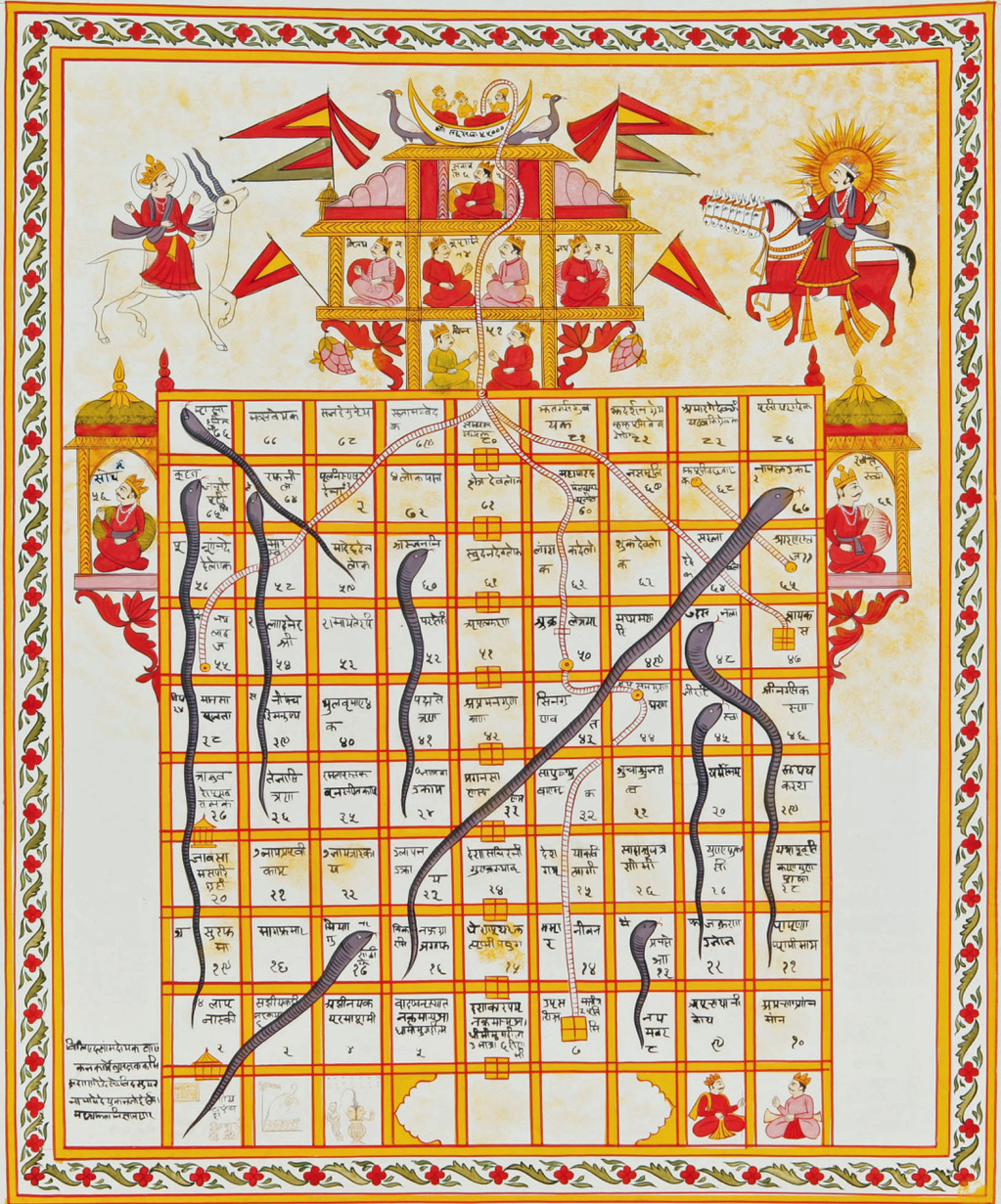

It is striking how this pattern of rise and fall—of virtue as ascent and vice as weight—has been intentionally embedded in quotidian Indian objects, games, and textiles. One such game, Moksha Patam, is the original Indian version of Snakes and Ladders. Designed to teach children that good conduct leads one upward while moral lapses pull you down, the game turns philosophy into an experience, repeatedly ingraining into young minds the thrill of ascending to the summit with the help of virtuous ladders and by avoiding the vicious serpents along the way.

Ancient Indian game of Moksha Patam: By Jain Miniature – http://www.herenow4u.net/index.php?id=72923, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11471979

When he finally reaches the gates of Swarga alone, Yudhishthir finds no trace of his loved ones and is beside himself, seeing his adversaries, the Kauravas, enjoying life in Paradise. It is only through complete renunciation of his kin as well as his prejudices that he is finally admitted into Vaikuntha, the eternal heaven beyond Swarga.

Two Heavens

In Hindu mythology, the concept of Heaven is split into two levels, one is material heaven, or Swarga, a temporary paradise granted through virtuous living, and the other is Vaikuntha, a permanent spiritual respite attained through renunciation of the mortal world.

Swarga is the celestial abode of the Devas, ruled by Indra, and brimming with pleasures, luxuries, and fulfilled desires. But this paradise is still within samsara—the eternal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. A soul in Swarga eventually returns to the material world once the merits of its karma are exhausted.

Vaikuntha, by contrast, lies beyond the pull of desire and the weight of karma. It is not a reward, but a release. As the abode of Vishnu, the supreme God, Vaikuntha offers liberation from all cycles—moksha through renunciation, detachment, and stillness. Entry into Vaikuntha requires not just good deeds, but the dissolution of ego and longing. As such, ascent to Vaikuntha can be considered a marker of a soul having achieved a higher state of spiritual evolution.

My first visual imagery of Swarga and Vaikuntha was shaped by BR Chopra’s Mahabharat TV series on Doordarshan, which I watched as a child. The narrative would begin on earth, where mortals grappled with fate, dharma, and the consequences of karma. Then, in a slow, theatrical sweep, the visual would lift upward, panning to somewhere between the sky and outer space, revealing Swarga, where the Devas observed the human realm from above. In their moments of helplessness (often credited to their adversary Asuras), the Devas would look further upwards through glittering galaxies, toward Vishnu in Vaikuntha. There, beyond the tumult, Vishnu lay in serene stillness on the coils of his serpent Adi Shesha, resting within a heavenly lotus.

This visual progression—from human turmoil to divine action, and finally to cosmic stillness—etched a vertical hierarchy into my young mind. It became a metaphysical map: Earth as the realm of struggle, Swarga as the domain of desire and duty, and Vaikuntha as the still, serene source beyond both.

For me, the two heavens reflect the difference between external reward and internal stillness. Swarga is where every mortal wish comes true; Vaikuntha is where the need to wish disappears. This vertical cosmology mirrors how I’ve now come to think about my work: shaped by the push and pull of desire and detachment, where making something beautiful becomes a way of asking deeper questions, and where jewellery is both an object of desire and a reminder for release.

It is perhaps this duality that led me to create Aham, a ghee lamp, as part of my Wishing Tree series.

Aham, meaning “self,” is my infinite identity.

When lit, its wax tongues melt like dissolving ego, into the pot of ghee at its base, illuminating the inner lamp of knowing while unifying the identity with the source.

Surabhi Sahgal, Aham, Ghee Lamp from my series – Wishing Tree, Patinated copper, brass, moli dhaga, wax tongues, incense, chains; 215mm (w) x 72mm (d) x 215mm (h)

Samudra Manthan

The Devas, despite being the residents of the paradise of Swarga, were plagued by their recurring conflicts with their adversary, the Asuras, and sought Amrita, the Elixir of Immortality, to vanquish the Asuras permanently and rid themselves of their insecurities of cyclical loss and triumph.

But they could not retrieve it alone.

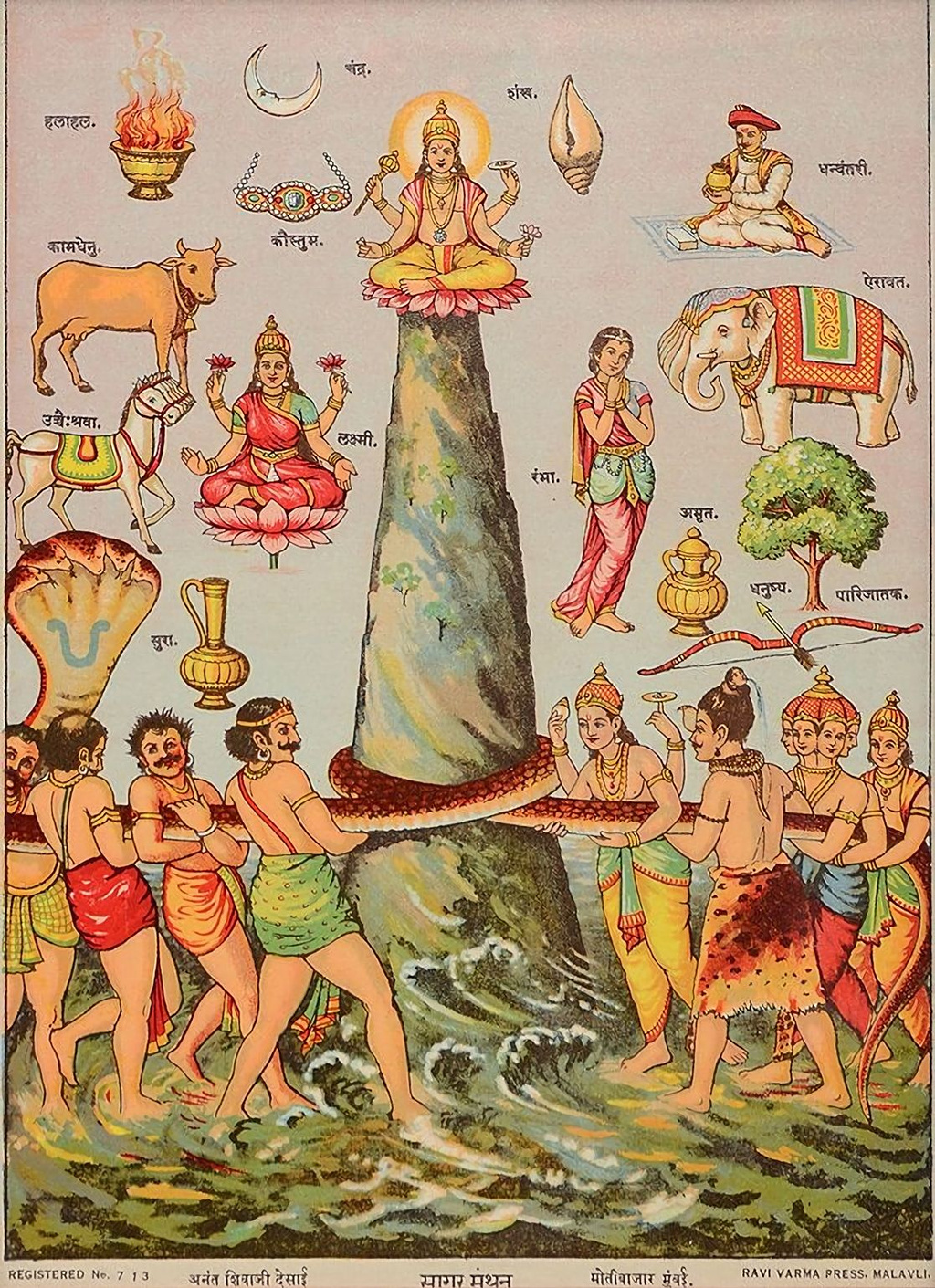

On Vishnu’s counsel, the Devas joined forces with the Asuras to churn Ksheersagar—the Ocean of Milk. Mount Mandhar became their churning axis, and Shiva’s serpent Vasuki their churning rope. At the horizon between Swarga (Heaven) and Pataal (Underworld) an unlikely collaboration between the equal and opposite forces of the celestial Devas and subterranean Asuras—led to a long and turbulent churn, one that brought forth both divine treasures and deadly poison.

Devas and Asuras churning the Ocean of Milk, an illustration by Raja Ravi Varma: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sagar_Manthan.jpg

Much has been written about the treasures that emerged, including Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, apsaras, divine beings, Kamdhenu, the wish-fulfilling cow, Parijat, the wishing tree and finally Amrita itself. But before these came Halahal: the toxic venom spewed out by Vasuki as a byproduct of the churning, so potent that it threatened to destroy all creation. To preserve humanity, Shiva swallowed this venom, his selfless sacrifice earning him the name Neelkanth (the one with the blue throat).

Vasuki Necklace from my Nirankaar Series based on Shiva, the Hindu God of destruction, 2021; electroformed and patinated copper

As a child, I may have gawked at visuals of the dazzling outcomes of the churn – divine jewels, celestial beings, and magical trees. But the real treasure lay in what the Devas sought from the exercise: Amrita, a symbolic means of their release from the loop of insecurity, desire, and defeat.

Dualities of the Churn

The Samudra Manthan has long served as a metaphor for the human psyche: an ocean of dormant knowledge and inexplicable capacities, waiting to be stirred to consciousness through pressure and paradox. In the Samudra Manthan, both divine treasures and dangerous poison emerged from under the ocean, symbolising the dual outcomes of inner turmoil. It took the cooperation of opposite forces, celestial Devas and subterranean Asuras. The churning rope, Vasuki and the Churning Axis, Mount Mandhar, together represent the balance between force and surrender. Seeking a tactile, material representation of these metaphoric dualities, I created the Manthan series, a collection of sculptural rings imagined as relics of the inner and cosmic churn.

Relics of the Churn – My Manthan Series

My Manthan series of rings depicting turbulence (Ocean Spray), Unwavering Axis (Kailash), Material Ratnas (Emergence), Coiled glory of Vasuki (Serpentree), Elixir (Amrita), venom (Halahal), time (patinated serpentree)

Exploiting copper’s dual material properties of growth and decay, the rings represent elements of the Manthan and its various emergences. Depicting a surface-level disturbance, Ocean Spray begins the churn, its aqua chalcedony drops, a vision of turbulent froth on the pristine ocean surface.

Coiled and textured Serpentree rings mimic the serpent Vasuki, depicting in their finishes the passage of time through patina and black venom through a coat of rhodium on the rugged shank surface. Vish is a picture of Halahal, the deadly poison emitted from the churn, decorated with black onyx drops, celebrating not just material and sublime wealth emerging from the churn, but also tension and toxicity that are essential byproducts of any transformative exercise.

Even the coveted Amrita, depicted as a citrine accent, sits within the grip of dark and godly forces alike. It felt fitting that the electroforming process mirrored the dualities of the churn, demanding both control and surrender, dissolution and growth, toward a slow accumulation of copper layers on the rings, through a literal dance between the positive and negative.

- Making Amrit: The central piece in the Manthan series, depicting the coveted Amrita: the elixir of immortality

As such, Manthan is a tribute to the hard trials and ensuing sweet successes of life, the sum total of which gives purpose to human existence. Together, the wearable relics acknowledge that even heavenly beings must churn their depths to yield transformation and abundance.

But beyond the desires of humans and heaven sits the last relic, Kailash. Kailash is the summit of spiritual transcendence. What remains after the turmoil of want and have? The axis aligns the soul with the divine. The unmoving centre that moves one to respite.

- Making Kailash: a tactile representation of the void of detachment

- Making Kailash: a tactile representation of the void of detachment

The ring began as an unassuming coil of copper wires submerged in the electroforming bath. I let layers of copper grow deliberately wild, manipulating and filing away the interiors for wearability. Over time, the ring was covered in ferny copper forests, much like the untamed shrubbery of the isolated Kailash Mountain. The ring did not compete with the other relics for ratnas and dazzling finishes. Instead, it was sandblasted and silver plated, giving it an ashen, subdued quality mimicking the meditative stillness of Shiva. A faint silhouette on a distant horizon, it is a transmitter of myth, a totem of ascension. Like Mount Kailash, it holds space for paradox—detachment within form, movement in stillness.

- Kailash ring, 2025

If Manthan represents the pursuit of desire and abundance, then Kailash reflects detachment that transcends it. Just as Mount Mandhar stood as the unyielding axis during the transformative churn, Kailash endures as the still centre that remains after. It reflects a state beyond striving: a moral clarity that anchors the self.

On my finger, the ring becomes a personal compass. It hugs the fate lines of my palm— yet sits within my grasp, reminding me that the path ahead is shaped by action. A meditation in material form, it connects thought to body, symbol to self. The final journey is not outward, but inward.

Further Reading

Origin of Snakes and Ladders or Moksha Patam and its relationship to virtuous living

Another reference to Moksha Patam – incorporating the dharmic phases of life in the game of Snakes and ladders

Devvdutt Pattnaik on life as a game of fate and free will:

Article on Mount Kailash – Centre of the Universe .

As Brianna Wiest writes in The Mountain Is You, “The mountain is not something to be climbed; it is something to be overcome from within.” That is what Kailash has come to mean to me. A symbol of stillness after struggle. Not the reward, but the reckoning. Not an escape, but a return to the self.

Surabhi Sahgal

I am an Indian maker of visual and wearable art, based in Chandigarh. Trained as an architect, I transitioned into contemporary jewellery to explore material stories on a more intimate scale — using copper, patina, and electroforming as mediums to reflect on dualities of growth and decay, environmental crisis, and personal interpretations of Indian mythology.

I am an Indian maker of visual and wearable art, based in Chandigarh. Trained as an architect, I transitioned into contemporary jewellery to explore material stories on a more intimate scale — using copper, patina, and electroforming as mediums to reflect on dualities of growth and decay, environmental crisis, and personal interpretations of Indian mythology.