Garlands have been used in many cultures across the world as symbols of purity, beauty, peace, love and passion. Flowers, leaves and foliage, delicately strung into garlands, wreaths (circular arrangement), chaplets (flaunted on the head), etc. have been worn as adornments or hung as decorations since time immemorial.

In ancient Egypt, flowers had symbolic meaning with emphasis on religious significance; garlands of flowers were placed on the mummies as a sign of celebrating afterlife. The ancient Greeks and Romans used flowers and herbs as adornments to be worn and to decorate their homes, civic buildings, and temples. In contemporary times, the usage and production of garlands have been more elaborate in Asia than elsewhere. Like the Thai have their phuang malai and the Hawaiians, their lei; the Indians have their mala or haar.

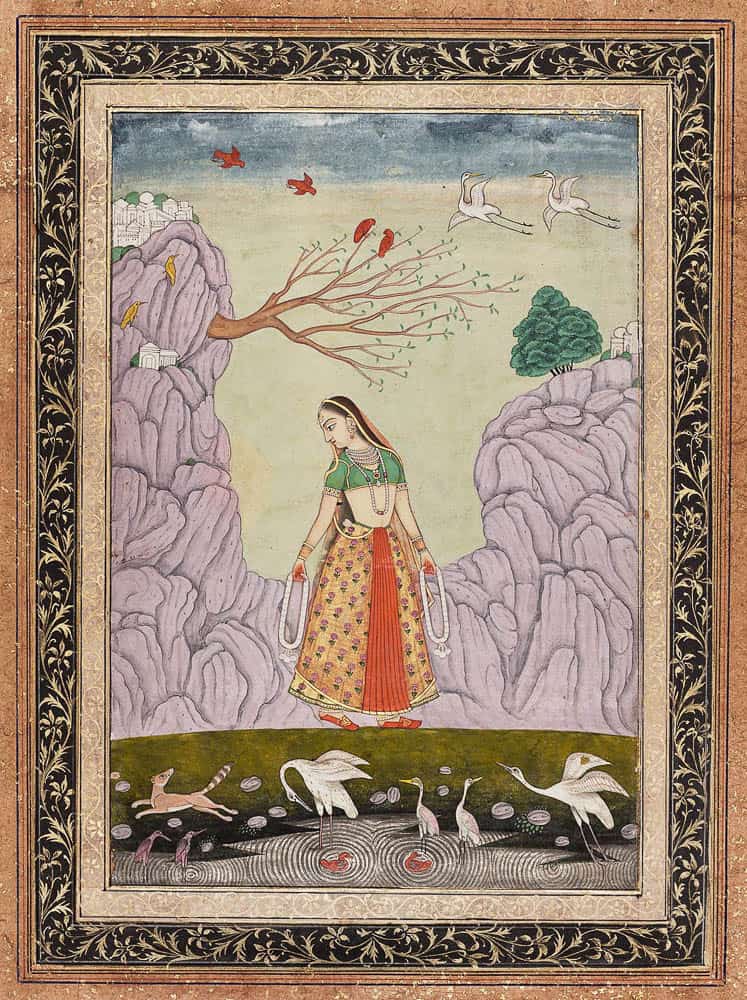

In the early Hindu society, the use of flowers was secular. Indian culture enjoyed the scent of fresh flowers at ceremonies; garlands were sought after for their splendour as well as fragrance. Flowers, in the form of a mala (garland), were utilised for the adoration of gods, men and women. Garlands used by women as hair adornments are known as gajrai; fragrant flowers like the jasmine are the most preferred as hair adornments. The Ramayana refers to personal floral decorations used by women, including the use of lotus or jasmine flowers in the hair, and men wore floral garlands, especially in the bedroom. The gift of garland was connected with courting and marriage; according to the Manav Dharmashatra, or the Laws of Manu, it was permissible to send a woman flowers or perfume providing she was free. Comparably, a garland is a preferred prop, for a recurring theme Indian literature as well as painting, i.e. – ‘women seeking their lovers.’ For example, in the Ragamala (garland of musical modes) paintings, some melodies are represented as women waiting for their lover with garlands in their hands. The tradition of varamala (garland for the bridegroom) originated from the ancient ritual of svayamvara (the act of selecting a groom by self-choice), a type of marriage where a princess selected her husband from a public assembly of suitors by placing a flower garland around his neck. The most well-known svayamvara appear in the Vedic epics of Indian literature, i.e., Sita’s svayamvara in Ramayana and Draupadi’s in Mahabharata. Even today, in traditional Indian marriages, the ritual of a bride garlanding a groom marks the commencement of wedding ceremonies.

- Kakubha Ragini (a folio form Ragamala series) Object place: possibly Hyderabad, Deccan, India Date: 18th century Source: www.mfa.org

- Kaisari Ragini (a folio from Ragamala series) Object place: India Date: 18th century Source: Flicker – The San Diego Museum of Art

- Bride and groom on their wedding day, wearing garlands of rose and jasmine, being blessed by elders. Place: Gujarat, India; Source: Author

- A series of shops outside a temple sell garlands and sweetmeats for the purpose offerings to the deities. Place: India; Source: Flicker – Jon Connell

- The garlanding ritual whereby the bride receives the groom upon his arrival (at the wedding venue). This ritual marks the commencement of the elaborate wedding ceremony. Place: Gujarat, India; photo: Author

Flowers are yet more important in religious rituals. Garlands serve as offerings to the gods in magnificent temples, in domestic rituals, and in public ceremonies of devotion. The name of the Hindu worship ritual ‘puja’ that translates to the “flower act” emphasises the significance of flowers in the religious context. In the past, it was customary for Brahmans to gather flowers after bathing. Flower trade is a booming industry in India even today and famous flower markets are a must on the bucket list for tourists visiting India. Garlands can be purchased from stalls in the town or even home delivered for the everyday puja. Having been brought up in a Brahman family, I have had the privilege to witness my father perform the puja every morning, clad in a dhoti (traditional attire) in an accurate Brahman flair. In our home, the usual offerings to the many gods of the pantheon include offerings of garlands, lighted lamps, incense and vermilion powder. On special occasions, there is an addition of sweetmeats as prasad (food offerings made to god). In temples and elaborate pujas, the offerings mentioned above are paired with coconut, clothing, jewels, perfumes, music, dance, betel, fruit, etc. The offerings are seen as a gift to be enjoyed, of the same kind that one would offer to humans. In this regard, flowers are the food of the spirit, a sign of respect and love. At the time of performing homa (or havana, a form of fire worship) on auspicious occasions like weddings, house-warming, and other worships, the individuals taking part in the worship are also made to wear garlands. This is so because the act of taking part in a religious worship is considered honourable.

- The idols of Krishna and Radharani, beautifully adorned in fine clothes and garlands at the Krishna Balarama temple. Place: Vrindavan, India; Source: Sahadeva

- Deities in a house-temple adorned with flower garland and offerings of flowers. Place: Gujarat, India; Source: Author

- Different forms of gods and goddesses adorned with garlands of marigold during a puja. Place: Gujarat, India; Source: Author

- Members of a family taking part in puja also wearing garlands of marigold. Place: Gujarat, India; Source: Author

Sweet-scented flowers are more preferred than others for making garlands. In India, the most preferred flowers for garlands are red roses, spider lilies, frangipani, paras, jasmine, and marigolds. However, there is more substance with regard to the use of flowers in a religious context. Particular blossoms are linked to particular deities: for example, a garland made of durva (grass) is preferred for Ganesha (the elephant headed god); for Hanuman (an ardent devotee of Lord Rama), a garland of ankada (crown flower); for Shiva, that of dhatura (moonflower); for goddess Kali, that of red hibiscus, etc. That is so because it is believed that the characteristics of certain flowers are more suited to specific deities. For example, the petals of the red hibiscus resemble the tongue like that goddess Kali put out when she stepped on Shiva. As per Hindu mythology, the lotus has ever been conceived as the symbol of purity and charm; it is considered that within everyone resides the spirit of the sacred lotus flower. Each colour of the lotus is sacred to one aspect of the Hindu trinity: the blush coloured lotus is the flower of sunrise, Brahma’s prayer; the blue is sacred to Vishnu, upholder of the blue noontide universe; the white is the flower of evening, the flower of death and resurrection, the emblem of Siva, destroyer and preserver. Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, sits on a lotus throne with a lotus footstool, holding a lotus flower in her hand. Flowers and their symbolism as per the Hindu mythology can become an entire subject in itself!

- An auto-rikshaw adorned with a garland and banaba leaves during a festive occasion. Place: Tamil Nadu, India; Source: Flicker – McKay Savage

- Entrance of a residence decorated with torana made of different flowers and leaves. Place: Gujarat, India; Source: Author

Garlands are not only used to decorate gods and individuals but also roads, houses, palaces, and even cities. During auspicious occasions, the frame of the entrance, which marks the threshold of a house, is decorated with torana (garlands made of flowers and leaves) as a symbol of welcome. As per Indian customs, the initiation of a new activity—be it a passage of rite, or acquisition of new possessions such as a vehicle or a home, etc.—is graced with the usage of garlands. On the festival of Dussehra, people use garlands to decorate their tools or vehicle on which they depend for their livelihood, recalling the worship of weapons in the Ramayana. Family members embarking on or returning from long journeys are also bedecked with garlands as a sign of good luck and welcome respectively. Welcoming guests with a high degree of hospitality is ingrained in the Indian culture. Considering that the tradition of welcoming guests is based on the ancient Indian dictum Atithi Devo bhava that translates to “may the guest be a god unto you”; it is only apt that, like the gods, the guests are also welcomed with garlands as a symbol of good will and honour.

The perishable nature of a garland is indicative of the fragility of human sentiments. Nonetheless, despite their short-lived lifespan, garlands remain a medium to express sentiments of purity, honour, goodwill, love, and beauty. In such a large and diverse nation that India is, many differences occur with regard to the use of garlands. Some differences are highly local, whereas others, broadly regional. However, the symbolism imparted by flower garlands in ancient Indian culture holds true even today.

Further reading

Buchmann, Stephen. 2016. The Reason for Flowers: Their History, Culture, Biology, and How They Change Our Lives. Reprint edition. New York: Scribner.

Goody, Jack. 1993. The Culture of Flowers. CUP Archive.

Herbert, Eugenia W. 2013. Flora’s Empire: British Gardens in India. Penguin Books Limited.

Rhind, Jennifer Peace. 2013. Fragrance and Wellbeing: Plant Aromatics and Their Influence on the Psyche. 1 edition. London ; Philadelphia: Singing Dragon. Flowers, Jack Goody

Author

Mitraja Vyas is an interior architect and a design researcher. Her research interests lie in disciplines that hold indigenous crafts at their core. She has been actively involved in the study of indigenous Indian crafts and their applications in the realm of contemporary interior architecture and design. A particular research subject that she is keen about is – world furniture in general and vernacular furniture in particular. Mitraja hails from Gujarat, India, and has recently relocated to Melbourne, Australia. She is a freelance research associate at the Design Innovation and Craft Resource Centre (DICRC), CEPT University, India, where she began her career as a researcher in 2013. At present, Mitraja is authoring a book on the vernacular furniture of Gujarat. The book is an outcome of Phase: 1 (Gujarat) of an international research project titled Vernacular Furniture of North-West India. The project is a collaborative initiative by DICRC, CEPT University and the SADACC Trust, UK.

Mitraja Vyas is an interior architect and a design researcher. Her research interests lie in disciplines that hold indigenous crafts at their core. She has been actively involved in the study of indigenous Indian crafts and their applications in the realm of contemporary interior architecture and design. A particular research subject that she is keen about is – world furniture in general and vernacular furniture in particular. Mitraja hails from Gujarat, India, and has recently relocated to Melbourne, Australia. She is a freelance research associate at the Design Innovation and Craft Resource Centre (DICRC), CEPT University, India, where she began her career as a researcher in 2013. At present, Mitraja is authoring a book on the vernacular furniture of Gujarat. The book is an outcome of Phase: 1 (Gujarat) of an international research project titled Vernacular Furniture of North-West India. The project is a collaborative initiative by DICRC, CEPT University and the SADACC Trust, UK.

If you enjoyed this article, please sign up to our email newsletter for more stories to adorn 🌸 your inbox.

Comments

can i have more info about this garland’s ..

thank you, i know have much better understanding of our culture, thank you.

This is a beautifully written/researched article. The perfume of the words lingers deep and long in our minds just like fragrance from the flowers! Jai Ho.

Roopa’s creation in YouTube channel is introducing how to make garlands from fresh flowers..

Thanks for the beautiful article .

Can we Cary flowver garlant in flight

A sentence or a verse is a g’land of words into the thread (dhaga) of feelings in our ❤ where whom offered ever stay free & concerned well⚘..