Kaustav Chatterjee pays homage to the practice of decorating thresholds and the way it fosters local community life.

(A message to the reader.)

Any metropolitan city in India with a population of more than four million has enclosed narrow lanes which are mostly owned by the residents in many ways, whether it is extending the building part into the street or having winter chitchat in the mid-sun. These all other tangible-intangible human actions are happening in the inner streets which are free from the bombarded constructions of the metro railway along the high road. In such intimate lanes, away from the high road, where someone can walk without the fear of a giant truck behind, someone is carefully drawing the street/floor, muggulu.

Muggu or muggulu (plural) is a prevalent practice of ephemeral floor design with decorative patterns in some parts of southern India (in some parts known as “kolam”) that has been transmitted by generations and is a crossroads of local knowledge and visual vocabulary. A particular visual art form is usually performed by women on the threshold of a house. It is traditionally done by washing, staining the floor with cow dung, then drawing the lines, dots, and geometric forms with rice flour and sometimes with other crushed colourful edible materials, as it is supposed to be eaten by ants and birds, get walked on, blown away in the wind throughout the day, as a recurring process for making a new one the next day.

- Muggu in front of a house in Hyderabad, India, 2023, Photo: Author

- Muggu in public interaction in front of a house in Hyderabad, India, 2023, Photo: Author

I live in a lane in a city with many lanes in southern India, where muggu in the streets in front of every house is a life practice, a significant cultural idiom. My first interaction with muggu is sudden, leaping the design over to keep it intact while entering into a house over the legacy of local epics to historical intercontinental translocalization.

I just entered the lanes of a closed neighbourhood, walking by the streets, smelling the spicy air around a fast food corner, hearing the machine sound from a tailor shop, the metallic sound of a barber’s busy scissors and seeing the series of muggu designs on the streets, being careful (about history or the piece of art?), not to destroy this outdoor museum. My encounter in a certain location as a practising artist questions the nuances of academic art endeavours toward more non-anthropogenic norms. Practising art/craft on the streets that is tremendously ephemeral opens up multiple (a)venues of disownment and performing life.

Embodiment and Action

The tenets of performing life in a metropolitan city are conceived in terms of the widely acclaimed idea of development blooming into highrise buildings and highways, and theme parks where the idea of street rises up to the sky. The city of Hyderabad is on the same path. Dr Baishali Ghosh has penned the historiography of the contemporaneity of its streets and transformation in her chapter titled “Thinking through the Residual Shrines on the Roads of SEZ Hyderabad”. While the streetscape of the city is in construction, I am looking at changing the streetscape through an act of gestural mark-making as experienced with hand and body by the maker and viewer at the Entry/exit of a home and the street. So far, this proposes a making of art by the street, of the street, for the street, or, often said inward “street art” (?) by the women who cook and care for the interior world.

I grew up seeing women performing/ making “alpona” in a different process in eastern India as floor designs or decorating/embodying the street to the home. The very designs are interlocating in other mediums and also in needlework by women. There are multiple practices of floor designing in all the different locations with different names throughout the Indian subcontinent majorly recognized as the action of “Shubha”/Auspicious. Here muggulu is believed to bring prosperity to the household, welcoming the world inside that is being co-habitated by the pluriverse of humanism. It presents a transpersonal site on the street during the making process while exchanging emotions with the exterior world every day. Though it is not the only access to the street for them, women eventually, just after making the muggu, take their bags and leave for work outside by crossing over their recreated interior on the street.

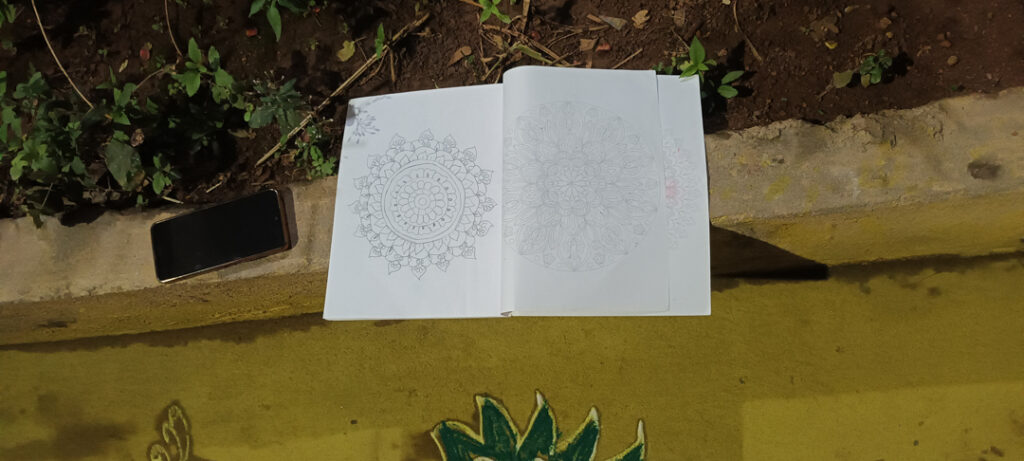

Sunitha Ji, a woman who helps my rented apartment’s owner lady with everyday household work, is responsible for making the muggu in front of our house every morning after washing away yesterday’s design. In the morning while I leave my room to reach my destination, she does her Muggu on the street, following her unique energetic gesture through new exclusive designs every day. I used to have small interactions and leave while she was still making. After that, she must complete her assigned work and then also leave for another house to do the same job. Another neighbour, Anjali, an old lady, has a whole copy full of muggu designs that she has been drawing and collecting to decorate the street for generations. It is such an embodied knowledge practice that travels from mother to daughter whom I meet on the street while they are making, maybe in a mere morning or on a brilliant festival evening. Muggu became a major tool for performing aesthetics and perceiving streets as multisensory experiences.

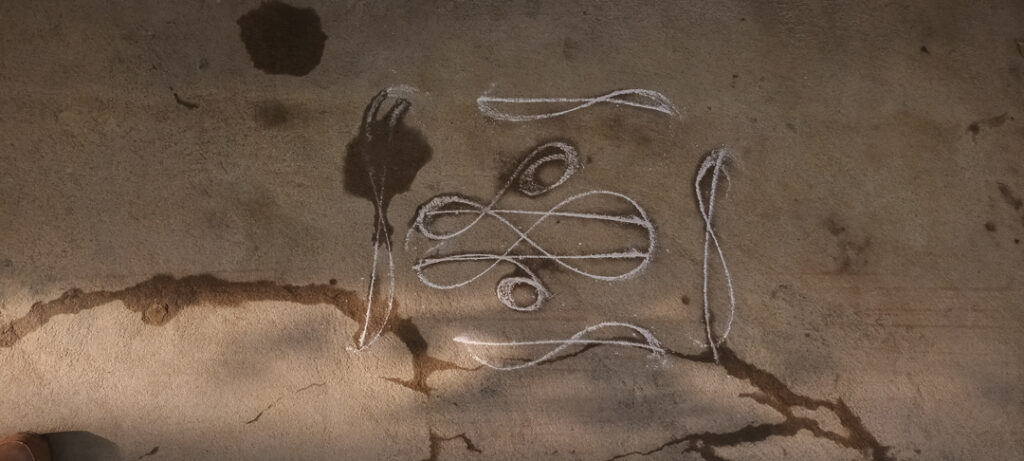

- Sunitha Ji’s Muggu in front of our home in Hyderabad, India, 2023, Photo: Author

- Muggu in front of a house in Hyderabad, India, 2024, Photo: Author

- Muggu and Anjali Ji’s sleepers In front of Anjali Ji’s home in Hyderabad, India, 2024, Photo: Author

Enacting the Cosmic

Experiencing the street has to deal with people. How about art? What about enacting art in public that is not street art, but art on the street done with cosmic dust, organic to chemical? It does not increase the economic value of a neighbourhood, but it can be practised silently against the evolving demographic composition and potential displacement of residents. Formally, it is done on a yellow-stained (cow dung) floor with the white of rice flour, yellow of turmeric, and Natural red of “Kumkuma”, as Dr Rajarshi Sengupta also informs tamarind “kumkuma” as a red colouring agent in deccani cultural practice.

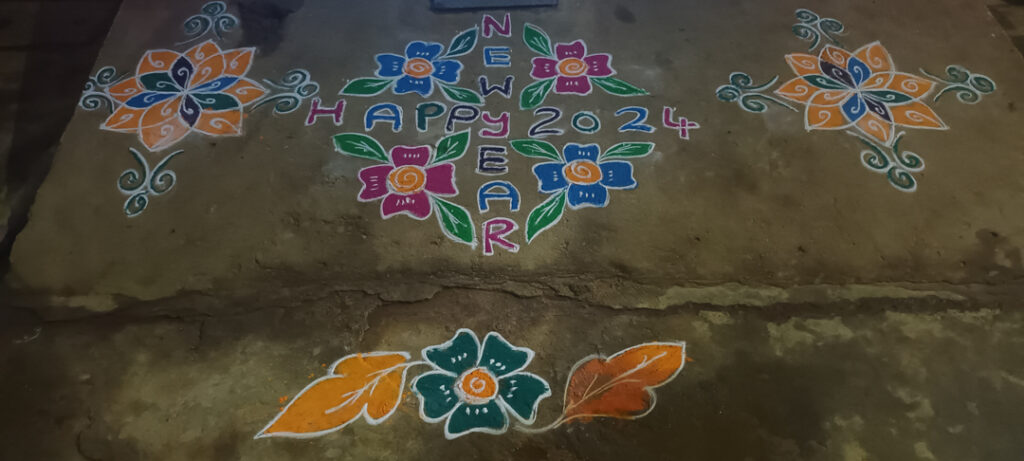

However, when I asked Anjali ji about the yellow floor where she was making a muggu, referring to her design collection copy, she informed me that the yellow colour is some cheap chemical colour available in the market most people are using nowadays. Since it was the night of the thirty-first of December, the whole para (neighbourhood) was in the street doing muggu to celebrate/welcome the very New Year in a closed, narrow lane of a south Indian State. First, I saw the use of chemical colour in the design also. While everyday muggu is made using white, red, and yellow organic substances, the festive muggu adds more colour by using some other colourful chemical powder available in the bazaar.

Even the designs are different in terms of welcoming the New Year. It is clearly understood that these are the modern adaptations of inter-localised elements of gentrification. It has been three months since I have been living in a locality making muggu, seeing the practice by women in everyday life and local festivals as well. During Sankranti, a harvest festival celebrated across the Indian subcontinent, muggu comes out on a larger scale. On the very second day of Sankranti, they make rathas/chariots in linear form, applying very few colours as part of rituals. In rituals with other elements of harvesting, the chariot appears as an ephemeral, two-dimensional structure proposing the arrival and departure of the god Vengkateswara (Vishnu) at the very door of a domestic house adjacent to the street. Rathas are also meant for the streets, as it is a form of vehicle, exuberant ornamented, celebrated on the street.

So far, as an enjambment of interior and exterior, rituals, beliefs, and cosmic relocations, this decorative art practice perceives the plural human history through bodies, lines, oratories and practice in the private and public world connecting the human and non-human.

- Shop of a temporary street market in Hyderabad, India, 2024, Photo: Author

- Streets of 31st December, Hyderabad, India, 2023, Photo: Author

- Streets of 31st December, Hyderabad, India, 2023, Photo:

- Anjali Ji’s Design Diary Hyderabad, India, 2023, Photo: Author

- Anjali Ji in Making Muggu, Hyderabad, India, 2023, Photo: Author

- Lakshmi Ji Completing Anjali Ji’s work, Hyderabad, India, 2023, Photo: Author

- Ratha Image in Muggu, Hyderabad, India, 2024, Photo: Tapati Roychoudhury

Further Reading

Ahmad, Perveen (2009), Bangladesh Kantha Art in Indo- Gangetic Matrix, Bangladesh: Bangladesh National Museum.

D’Mello, Melissa (2023), ‘Alpona: The Artistic Evolution Of A Folk Art Form’, Rooftop, Accessed 19 January 2024.

Dutta, Swarup (2011), ‘The Mystery of Indian Floor Paintings’, Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 14-27, Accessed 21 January 2024.

Ghosh, Baishali (2022), ‘Thinking through the Residual Shrines on the Roads of SEZ Hyderabad’, In S. Jha, and G. Bharat (eds), The Social Life of Streets in India, Histories, Contestations and Subjectivities, New Delhi: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 348-371.

Kolam (2024), ‘Rangoli Designs And Kolams’, Accessed 3 February 2024

Mapacademy (2022), ‘Muggu’, Accessed 27 January 2024

Mehta, Riju (2019), ‘Cost of living in ‘new’ metros: Hyderabad vs Bengaluru vs Ahmedabad vs Pune’, The Economic Times, Accessed 11 February 2024.

Sengupta, Rajarshi (2023), ‘ఎరుపు (Erupu): Reconstructing Red Dye of Kalamkari Textiles’, Decolonial Subversions, SI Vernacular Cultures of South Asia 2023–24, pp. 43–52.

YANAGISAWA, Kiwamu and NAGATA, Shojiro (2007), ‘Fundamental Study on Design System of Kolam Pattern’, Forma, 22, pp. 31–46.

About Kaustav Chatterjee

Kaustav is an art practitioner-writer-researcher in the fields of visual art and cultural studies closely involved with south Asian craft practices, embodied knowledge systems in practice and theoretical research. Kaustav proposes craft knowledge as a triangulation of archive, theory and everyday practice. It relocates the vision of craft as experience through art history, design studies, ecology, gender advocacy as an interlocutor of care as praxis. Kaustav has also formed a research project on theory and practice as discourse, currently working as a researcher in arts with Pleach India Foundation in Hyderabad, India. The city, where this written story is situated.

Kaustav is an art practitioner-writer-researcher in the fields of visual art and cultural studies closely involved with south Asian craft practices, embodied knowledge systems in practice and theoretical research. Kaustav proposes craft knowledge as a triangulation of archive, theory and everyday practice. It relocates the vision of craft as experience through art history, design studies, ecology, gender advocacy as an interlocutor of care as praxis. Kaustav has also formed a research project on theory and practice as discourse, currently working as a researcher in arts with Pleach India Foundation in Hyderabad, India. The city, where this written story is situated.

All the images have the copyright by Kaustav Chatterjee.