- Lisa Reihana, detail in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Ultra HD video, colour, sound, 64 min. Image courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice.

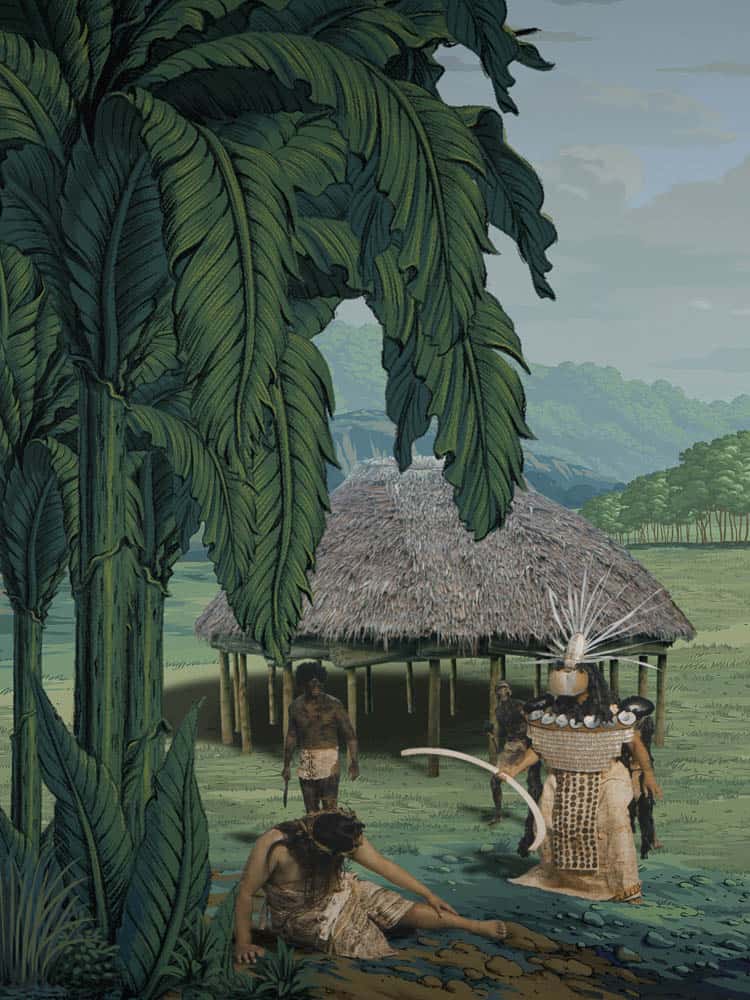

- Lisa Reihana, detail in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Ultra HD video, colour, sound, 64 min. Image courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice.

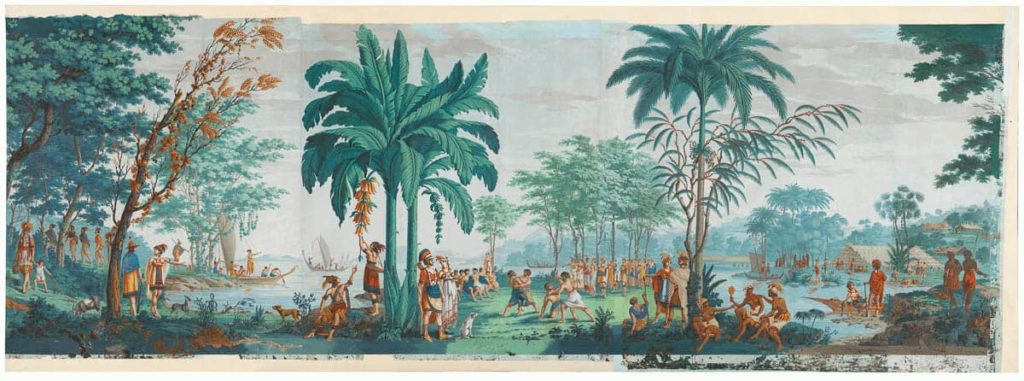

- Dufour et Cie, printer & publisher, Jean-Gabriel Charvet, designer The Voyages of Captain Cook (Les Sauvages de la mer Pacifique) 1805, woodblock, printed in colour from multiple blocks hand-painted gouache through stencils, printed image (overall) 170 x 1060 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, purchased from admission charges 1982–83.

This piece of text for Garland intends to be a garland itself, stringing together a series of ideas like blossoms. Bright or faded, buds or full-blown blooms, my garland threads its way through the lei as a form, Lisa Reihana’s epic video at the Venice Biennale, and ideas of social reciprocity.

Garlands thread their way through histories and cultures, from Grecian laurel wreaths, to pagan floral crowns, to strings of sacred orange marigolds adorning the temples of India. But it is Polynesian cultures of the Pacific that are definitively associated with threaded flowers, known as lei in Hawaii, with variations on that word existing in Tahiti and the Cook Islands, and other words denoting the floral garland elsewhere across the Moana. Here, I use the Hawaiian moniker, not because I have ever had the pleasure to visit those explosive isles, but perhaps because I watched too many Elvis films in my youth.

The Moana region itself might be thought of as a lei—strings of islands threaded together via throughlines of navigational routes—creating networks of shared knowledges and resources. It is perhaps a cliché now to quote the late Tongan scholar Epeli Hau’ofa’s “sea of islands” theory, in which Oceania is reimagined as a continent, its water a space of relation rather than separation. But cliché is a Western modernist construct, irrelevant to cultures with a productive, rather than fearful relationship with tradition. The recitation of familiar tropes is also a kind of verbal garland—like fingering rosary beads and murmuring mantras, or the Maori mihi and pepeha (welcome and genealogical recitation)—which links you, like a string of beads, to your ancestors.

Referencing Hau’ofa’s “sea of islands” has been part of a recitation amongst scholars of the Moana for at least the last decade, as well as acknowledging the vā or “space between” peoples, nature and culture, the sacred and the profane, as sites requiring constant tending in order to preserve harmonious relations. The Samoan phrase teu le vā which can be translated as “making beautiful” or “tending” this relational space, implies that small gestures such as the ritual use of flowers and other forms of decoration are more than aesthetic, serving social and metaphysical functions.

Certainly, bestowing lei on guests as a form of welcome is indelibly associated with the Pacific, reinforced by such gems of Western cultural production as The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. But what these pop cultural caricatures miss is that such warm welcomes across the Moana aren’t merely a matter of adornment, rather, guests are being gracefully enmeshed in social relations of response-ability (as Donna Haraway, who is fascinated by the entanglements of string games, puts it). Marcel Mauss demonstrated in his anthropological classic The Gift, via discussion of Polynesian modes of exchange, there is no such thing as a free lunch. I found this out when I flew to Rarotonga ten years ago for the wedding of New Zealand/ Cook Island artist Ani O’Neill and Croc Coulter, an Englishman trained in traditional tatau methods. Ani met me and a few others at the tiny, humid airport with fresh gardenia lei, whose heady tropical perfume, along with the airport’s in-house ukulele band, truly embraced me with “warm Pacific greetings”, that favoured catchphrase of the Moana diaspora.

But being a guest didn’t last long, a little like when staying on a Maori marae. Once the manuhiri or guests have crossed the sacred threshold of the marae āteā, have listened to the oratory, performed hongi with the tangata whenua, and had the customary cup of tea to break the spell of tapu, guests must demonstrate response-ability, and help out with the noa facts of life such as cooking and cleaning. In Rarotonga, no sooner had we been festooned with lei and driven to our lodgings, we were given huge sacks of fresh gardenias to string into lei for the next wave of guests. Teu le vā doesn’t just happen by itself.

I learned something about the way the Moana is strung together in that short stay on Rarotonga, as the place names echoed those back home in Aotearoa. One of the beaches was even known as the place where waka departed for that great journey south, demonstrating the connectivity of our sea of islands. This connectivity is something I only bear witness to, since my own genetic garland threads all the way back to Europe and isn’t encompassed by the necklace of the Pacific Islands. But friends and neighbours can be just as influential as family, and if there is one word to summarise what I am still learning from Moana people, it is humility. Guests will be made welcome, but guests must demonstrate response-ability, or there will be consequences, as Captain Cook found out in Hawaii.

- Lisa Reihana, detail in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Ultra HD video, colour, sound, 64 min. Image courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice.

- Lisa Reihana, detail in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Ultra HD video, colour, sound, 64 min. Image courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice.

- Lisa Reihana, detail in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Ultra HD video, colour, sound, 64 min. Image courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice.

- Lisa Reihana, detail in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Ultra HD video, colour, sound, 64 min. Image courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice.

- Lisa Reihana, detail in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Ultra HD video, colour, sound, 64 min. Image courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice.

- Lisa Reihana, detail in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Ultra HD video, colour, sound, 64 min. Image courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice.

- in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Lisa Reihana: Emissaries, Biennale Arte 2017. Photo: Michael Hall. Image courtesy of New Zealand at Venice.

- in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Lisa Reihana: Emissaries, Biennale Arte 2017. Photo: Michael Hall. Image courtesy of New Zealand at Venice.

- in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Lisa Reihana: Emissaries, Biennale Arte 2017. Photo: Michael Hall. Image courtesy of New Zealand at Venice.

Lisa Reihana’s in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015-17 is like a garland in structure: a panoramic video of vignettes strung together in a long line by a shared background of lush trees. The tropical greenery is based on French scenic wallpaper from 1805, called Les Sauvages De La Mer Pacifique, otherwise known as “Captain Cook’s voyages”. The wallpaper is hopelessly Arcadian, with Pacific belles mimicking the Three Graces; they would be more comfortable sporting laurel wreaths than lei. Reihana overturns this romanticisation-come-infantilisation, by creating spaces in her epic video for Moana people to represent themselves in prayer, play, dance and conversation. Each vignette blooms in the mind of the viewer before being superseded by the next, as they flow past like the waters of the great Ocean itself. Soon, the waters bring a ship, and soon after that, white men can be seen amongst the trees too. There follows a series of interactions, mostly well-meaning, all of them awkward. Eventually, there is a misunderstanding, and there are consequences. Protocols have been broken, ripped apart like a floral necklace, guests have misbehaved, and harmony cannot be restored. But Reihana’s video loops seamlessly back to its beginning; like a lei. This is the gift that Reihana bestows to the viewer—she presents a visual garland—and this denotes honour, but with that honour, comes responsibility.

How do pākehā, pālagi, non-Indigenous inhabitants of the Moana choose to live daily with the knowledge of colonisation? Of being uninvited guests, or guests who, after being welcomed, behaved badly? Who tore the proffered lei of reciprocal relations from our collective neck and stomped on the blooms? How can we teu le vā, tend relations, if the contract has already been rendered void?

Which is not to say that the lei itself has been robbed of its efficacy—far from it. This protean form is alive with possibilities, as demonstrated by the special collection curated by Simone LeAmon for the exhibition Art of the Pacific at the NGV in 2016. LeAmon undertook a whirlwind tour of the Moana, finding new twists on customary forms (see her article in this magazine). Subsequently, Art of the Pacific featured numerous contemporary variations on the Moana garland, including the use of seedpods, shells, sweets, plastic refuse, cast glass, and in the case of Chris Charteris, giant lei made from shells and rocks. But some aspects of Art of the Pacific still seemed to view Moana people as cultural decoration, as if it was their purpose to teu le vā for everyone, even misbehaving colonial guests.

In a recent issue of the Pacific Studies journal devoted to the Tā-Vā (Time Space) Theory of Reality, the editors, including Tongan scholar ‘Ōkusitino Māhina, challenge the emphasis on vā, or geographical, spatial, object-driven thought, and places this in a more productive relationship to tā, time, or processual relationships. The marking of tā (time) in vā (space) produces a range of artistic outcomes, including garlands, that sustain “harmonious and beautiful sociospatial relations”. The reintroduction of tā into vā, however, means that we cannot ignore the past (as Māhina et al are quick to remind readers, the past is in front of us, the future is behind us). Reihana’s looping narrative does just that; reactivating the vā by peeling back layers of history, as you would peel back layers of wallpaper in an old house. Such peeling doesn’t just expose injustice, but celebrates former lifeways and people, by actively tending their continuation in the present. The past lingers, like a blood stain, yes, but also like the scent of gardenia, the latter which permeated my pink mumu, standard issue for Rarotongan weddings, weeks after I returned home from that beautiful and humbling island.

Author

Tessa Laird is an artist and writer from Auckland, currently lecturing in Critical and Theoretical Studies at the School of Art, VCA and MCM, University of Melbourne. Her book on colour, A Rainbow Reader, was published by Clouds in 2013. Her book on bats, as part of Reaktion’s Animal series, is due in May 2018.

Tessa Laird is an artist and writer from Auckland, currently lecturing in Critical and Theoretical Studies at the School of Art, VCA and MCM, University of Melbourne. Her book on colour, A Rainbow Reader, was published by Clouds in 2013. Her book on bats, as part of Reaktion’s Animal series, is due in May 2018.