One remarkable feature of Japanese culture is the reverence for objects. We see this is in the tea ceremony that involves careful handling and appreciation of all its material components.

There is a genre of Japanese folktales about objects that acquire a life of their own. According to the myth of tsukumogami, objects can transform into creatures after they’ve been in continual use for 100 years.

The Japanese attitude towards objects contrasts with a consumerism that fetishises the new, where objects begin to lose value immediately after purchase.

But many involved in craft know that some of the most trusted tools have a timeless value. This online exhibition is a space to explore “the stories behind what we make” by acknowledging the lifelong contribution made by those favourite tools we could not make without.

Alice Whish | Ulvi Haagensen | Annette Nykiel | Ba An Le | Susan Fell Mclean | Jade Brockley | Shoso Shimbo | Edit Meaklim | Peter Walker | Karl Millard | Madhvi Subrahmanian | Sekar Ikanandanti H | Geoff Hogg | Bridget Nicholson | Merran Esson | Ema Shin | Naoki Sakai | Shinya Yamamura | Sheridan Kennedy | Andrea Barker | Behnaz Barabarian | Mitsuru Yokoyama |

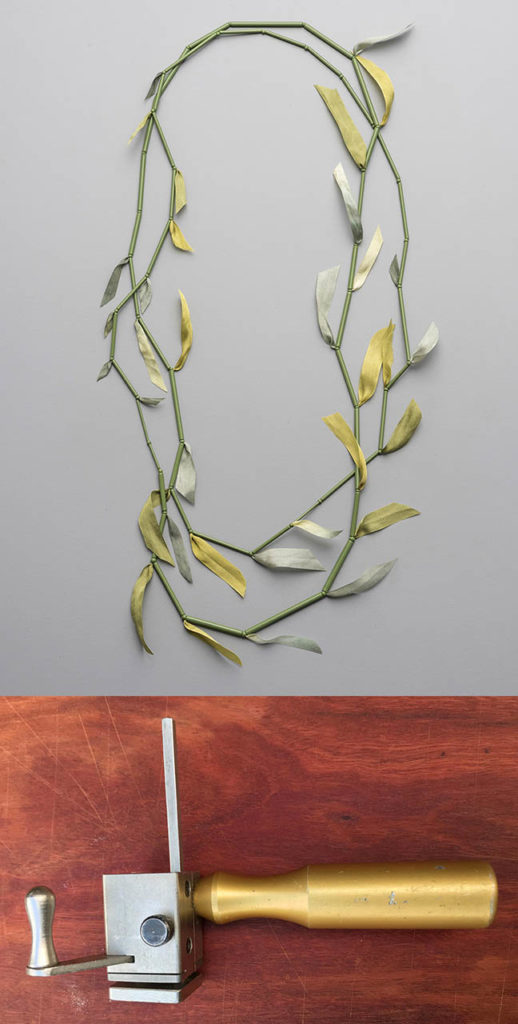

Alice Whish

Alice Whish, Necklace Soft Grass for Kangaroos, 2018, steel cable, brass powder coated and silk, H60cm x W4cm x D0.7cm, Photo Greg Piper

Alice Whish, Tool – Chenier Cutter, Purchased 1985, Steel and Aluminium, H12.8cm x W9.8cm x D4.6cm, photo: Alice Whish

Made in my studio in Sydney

This Soft Grass Necklace was made after an AIR at Bundanon in 2018 and while researching bush regeneration and cultural burning for an exhibition in 2019. My Italian chenier cutter was one of my first purchases in 1985. I love its slick modern anodised handle which is losing its golden colour here and there. It is beautifully weighted and a pleasure to pick up and use. I am always delighted when the problem to be solved requires that I reach out and use this tool for cutting a piece of fine tube. I enjoy using this tool so much that I have been known to unnecessarily cut a piece of 2mm wire with it.

Instagram: @alicewhishjewellery

Ulvi Haagensen

Ulvi Haagensen, Single feather duster, 2017, wood, paint, feather, 34 x 11 x 2cm, photo: Ulvi Haagensen

Tallinn, Estonia

The parts were hand sawn, painted and a feather was stuck in the end. It was made for doing pedantic cleaning. The paintbrush is special because I don’t care about it. It was cheap and that makes it so easy to use.

Instagram: @ulvihaagensen

Annette Nykiel

Annette Nykiel, Gathering Thought, 2017, plant dyed recycled cloth, finger plied string, seawrack approx 30 x 30 x 20 cm, photo: Annette Nykiel

Home made cotter pin netting needle, approx 7 x 1cm, photo: Annette Nykiel

Knotless netting basket made of finger plied rag string that has been solar dyed with windfall plants and earth pigments and used to collect seawrack and flotsam from the beach; part of the Gathering Thoughts assemblage in the Thresholds and Thoughtscapes exhibition at the Bunbury Regional Art Galleries, 2017. The homemade netting needle was fashioned from a cotter pin and has had many metres of finger-plied string and cloth strips drawn through it while netting or stitching baskets.

Ba An Le

Ba An Le, Evening Flash in the Dusking of the Sun, 2018, lapis lazuli, stabilised maple burl, gilt gold, 925 silver, dyneema cord, 23 x 21 x 1.8 cm, photo Ba An Le

Sydney, Australia

In my work, Evening Flash in the Dusking of the Sun, I use the lapis lazuli stone. I refer to the history of the ultramarine pigments reserved only for important and heavenly subjects. As a material that was difficult to source in antiquity, the translation of lapis lazuli into “beyond the sea” is both, literally beyond the land where one stayed, and symbolic for the heavenly and transcendent. However, my use of this stone is antithetical to holiness as I use it to make a serpent’s head which conveys evil. The serpent’s head circles around the neck of its wearer, completing the necklace form. Flowing into the serpent’s body are cast silver pieces and carved wood blocks that are elemental in nature to complement a cosmic unity of all things. Commonly known as the Ouroboros, the creature accompanies different traditional beliefs often alluding to the self-sustaining snake that marks the outer-most boundaries of the universe. In its transposition of the boundaries of the outermost to the neck of a human being, wearing the serpent is wearing the boundaries of humanity. The chisel that I used to carve the stabilised wood was an 8mm skew chisel that I have flattened on one plane. It became the most versatile chisel for what I am doing, making sharp and precise cuts. In the carving of the wooden pieces, I was guided by the wood grain, and my abstract imagination of snakes and waters, to evoke the mysterious.

Instagram: @baan_le

Susan Fell Mclean

Susan Fell Mclean, Seeking the Edge of the Fold, Repetition & Difference” 2018, Silk organza, mokume shibori, H:100cm x W:50cm x D:50cm, photo: Becci Zillig

Mullumbimby NSW Australia

Seeking the Edge of the Fold – Repetition and Difference’ is a shibori sculpture. With more than 2000 stitches, shaping a 3.5m length of silk organza to resist the dye extracted from the leaves of Eucalyptus cinerea, the common name of which is Argyle apple. This work was recently exhibited at Lismore Regional Gallery and Redland Art Gallery. In this piece, I used mokume shibori – My 40L stainless steel dye pot is responsible for an ongoing exploration of the beauty of colour from Australian eucalyptus leaves.

https://www.facebook.com/GondwanaTextiles

Instagram: @gondwanacolour/

Jade Brockley

Jade Brockley, Linen Twill Scarf, 2015, linen, L1700 x W250mm

Jade Brockley, Stick Shuttle, silver beech hardwood, L260 x W35 x H5mm

Melbourne, VIC

The Little Stick Shuttle. There are many types of shuttles one may use for holding weaving yarn. This stick shuttle is the most basic, often the type used when first learning to work on the loom. While most of my weaving friends have advanced to the smoothness and ease of boat shuttles, I have continued to be drawn to this simple piece of silver beech. This shuttle has been with me for over a decade, throughout my studies and studio in Melbourne, across the South Pacific to the tropics, and is now here with me in the Central Australian desert. I’m not sure why I’ve held onto it. It is covered in old tape and pen marks. There’s nothing fancy about it. It is one of many nondescript, mass-produced shuttles of its kind, and easily replicated if you have the skills to make your own. One can even make this style of shuttle out of cardboard, in a pinch. Perhaps I’ve kept it out of stubbornness, or some kind of superstition; a nostalgia maybe, linking back to my early days of weaving – of the beautiful weave studio, my all-time happy place, a room full of light and looms, where I spent many early mornings and late nights experimenting and learning. The woven object pictured is a simple linen scarf, woven in a balanced twill. My interest in weaving lies in process, material, and the bodily interactions inherent in the physicality of making and object use. Perhaps I enjoy working with this shuttle because it can only be used completely through the weaver. It must be laden with yarn by hand. There is no automation in its use; the weaver must literally pass it from one hand to the other. This simple little shuttle is a direct connection between the body, the material, the process and the finished work.

Instagram: @jadebrockley

Shoso Shimbo

Shoso Shimbo, Ikebana, 2018, Oncidium & other seasonal flowers, 100 X150X100

Genzo flower secateur, steel, 1.5x5X18

A Model Room, Kew, Melbourne

I made this ikebana for a model room of new townhouses in Kew, Melbourne. The secateur came from Sanjo city, Niigata, Japan. The city used to be well known for producing the top quality samurai swords, now producing domestic tools that are recognised worldwide. The city is next to my hometown, Gosen.

Instagram: @shoso_shimbo

Edit Meaklim

Edit Meaklim, Bushy Yates basket, 2009, cordyline eleocharis red hot poker, 21cm x 27cm

Edit Meaklim, rope splicing tool

Melbourne Victoria Australia

The basket was woven and embellished with bushy yates seed pods. It was for an exhibition ‘Tradition and Beyond ‘ Broken Hill Curated by Virginia Kaiser photograph by Bruce Tindale. The tool I most often use is called a FID or rope slicing tool used by chandlers. This tool creates a shed for fibres to pass through.

Instagram: @editke43

Peter Walker

Adelaide, South Australia

Hollow wooden surfboard commissioned as a parting gift from fellow workers after a 40-year career. A handmade board with the final and favourite tool being fire. A risky business at the end of a long hand making process where working with the tool (fire) produces semi predictable markings. Each fire has its own characteristics, as does the surfboard markings.

Instagram: @walker_surfboards

Karl Millard

- Karl Millard, Economy Grinder, 2018, copper, sterling silver, 290mmx85mmx90mm

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

The finished shape was formed over a block of iron that was found in a country paddock, and the tool i used to make it would be a pen to draw the symbols,

Madhvi Subrahmanian

Madhvi Subrahmanian, Mappa Mundi, 2017, 37″ x 34″ x 2″ Photo: Anil Rane

Buffalo horn, an invaluable tool for burnishing my works

Singapore

Instagram: @madhvi.subrahmanian

Sekar Ikanandanti H

Sekar Ikanandanti H, HUGs-Pelukan, 2018, reused copper plate/wire and bumblebee stone, 14 x 8.5 cm, photo : Sekar Ikanandanti

it was made at my workbench, in Jogjakarta, Indonesia

This pendant was made using basic metalsmithing technique (soldering) and the coloring/patina using stabilized liver of sulphur. The idea is about people always need hugs whenever the happy or sad and I choose the dramatic colour of bumblebee stone to complete my wabi-sabi style of work. The tools on the picture are my basic tools for every work I have made since early 2014 (the first time I learn about metalsmithing and start making jewellery).

Instagram: @sekar_ikahp, @sekar.makirtya

Geoff Hogg

Geoff Hogg, Intercambio Tickets, 2018, scrap cardboard on wood, 8cm x 5cm (6 examples of 750 works produced), photo:Geoff Hogg

Brunswick Melbourne

The work is part of the Intercambio project – a 4 year art research project developed as a part of CAST RMIT. The works are made from materials found along the Upfield Rail Line Melbourne and the Hershey Rail line Havana. Intercambio explores connections between the two sites through a series of creative projects. The tools featured – a set of blades, chisels and gouges that I have used since I was an art student in the 1960s. These tools were instrumental in creating the works featured.

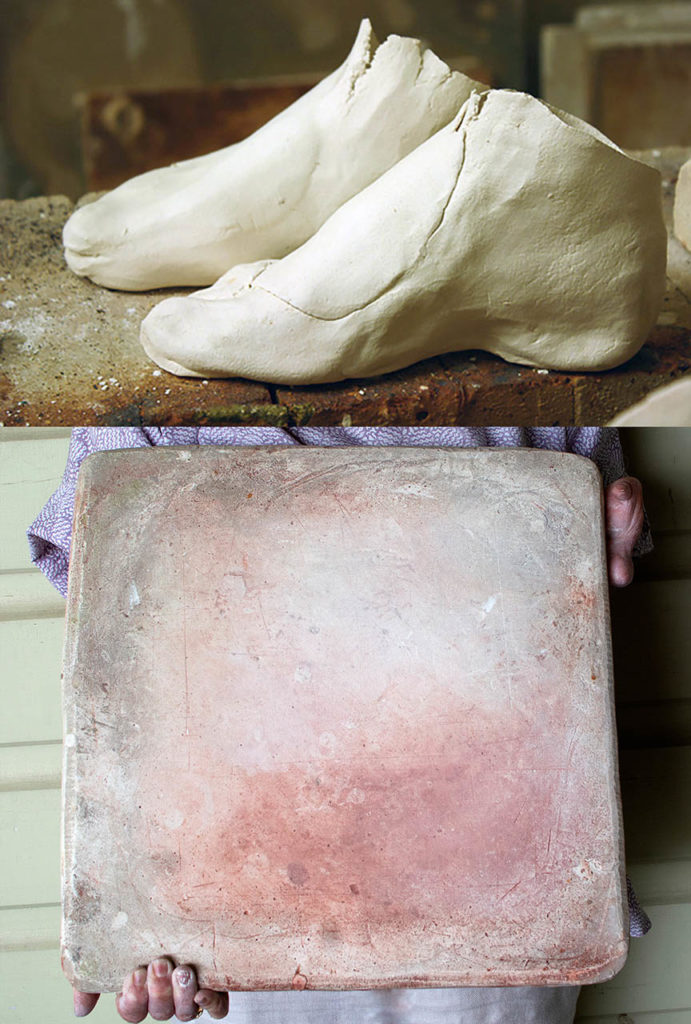

Bridget Nicholson

Canberra

The work is a collection of people’s stories about a relationship to land and place told through their feet. The collection holds 1000 pairs of ‘shoes’ from all over Australia and was made as a means of exploring emotional attachment to place at a time when mining, damming and other changes to land use were causing much debate within communities. The plaster slab was used to throw clay into flat sheets, like sheets of pastry, to then be wrapped and molded around the foot.

Han Dong

Han Dong, Necklace: Prehistoric Thousand Years, 2013

Han Dong, Jade fish, jade mask, jade coin, jade canal, jade canal, bronzes remnants, wuzhu coin, potteries, conch, turquoise, silver, wood, 20 x 2.5 x 53 cm; photo: Lei He

Beijing, China

Most of my work is done by hand in the studio, without the help of other workers or modern mechanical equipment. I like the feeling of primitive and natural. My jewelry works are small installations. I choose the relics of ancient ancestors and natural materials (shells, wood, feathers). The tools I use are simple, the sculpting knives are made by myself, and there are some basic tools for making metal.

klimt02.net/jewellers/dong-han

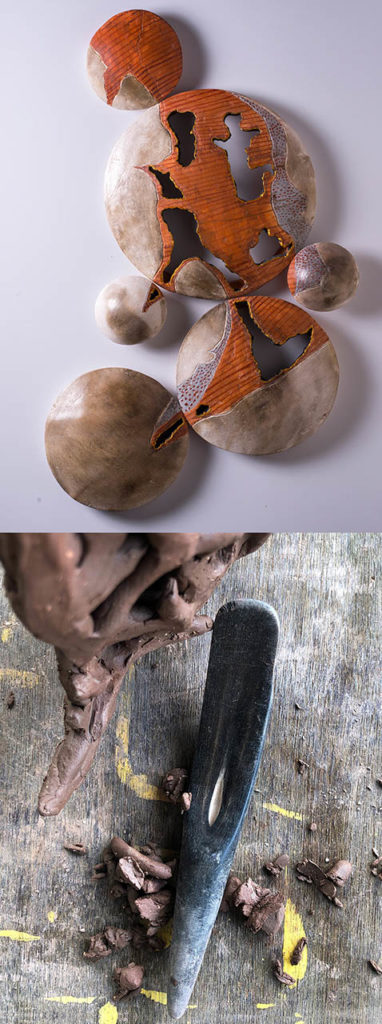

Merran Esson

- Merran Esson. Broken Bucket 2018 (detail). Photo: Greg Piper

- Merran Esson. 2014. 22x17x18cms; photo: Greg Piper

- Merran Esson, Fingers are my favourite tool; photo: Lucille Nobleza

Made in my studio in Sydney.

My tool might seem a bit cheeky, but my fingers have been dragging texture across slabs of clay for over 40 years. I am often asked to talk about the specific tool that I use. Of course I use a rolling pin to make the slab and a knife to cut the slab, however, it is my fingers that create the texture that my work has become recognised for. This tool arrived with me on the day of my birth, it has had many uses before I began using it to create lines that are a mnemonic device that refers to corrugated iron used on farm sheds and water tanks. Usually when I use this tool, it has already been used in the kitchen and in the office writing sentences and biographies such as this, more recently it has been overworked as iPhone technology also uses this tool, but it works best when there is a soft slab of clay upon which to leave an impression. I have often given workshops in many far flung places, and it has never been left behind. It goes through airport security without a question ever being asked about why its part of my travelling luggage.

Instagram: @merran_esson

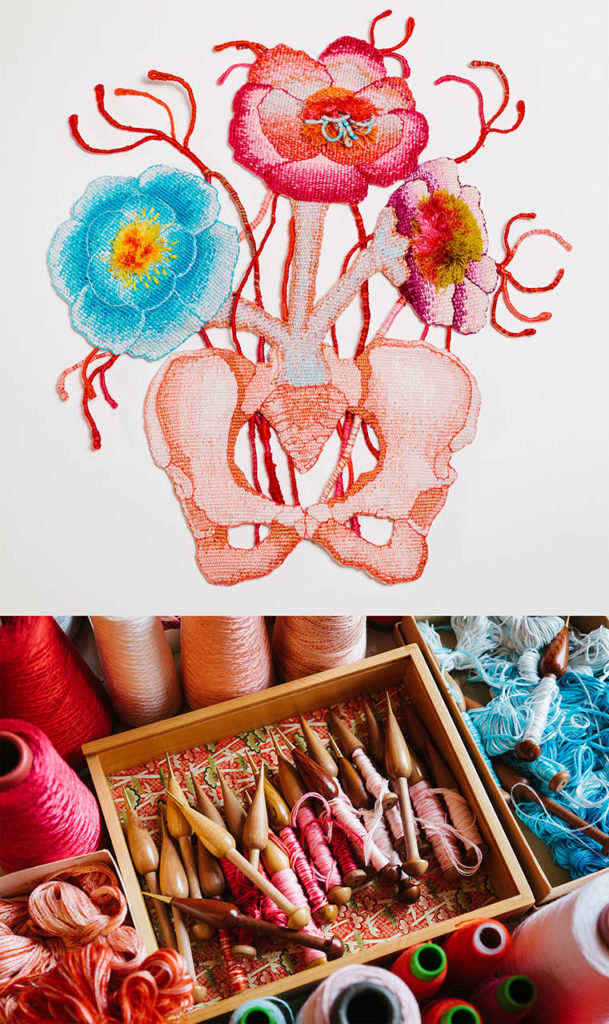

Ema Shin

Ema Shin-2jpg: Ema Shin, Soft Alchemy (My Pelvic Bone), 2018, cotton, rayon, wool, 50cm x 42cm x 3cm, Photo: Oleksandr Pogorilyi

Ema’s studio in Melbourne

This work is hand-woven tapestry. To start this tapestry, firstly I warp the cotton thread on the loom and make equal space in between each warped thread and set their tension. In accordance with plan drawings and colour samples, several colours of cotton or wool threads are mixed to create the right thickness of the weft yarn. Then in preparation for weaving, the colour matched yarns are wrapped on the bobbins. One of the most exciting moments is threading the first weft yarn with a bobbin into the warp and beating the threads down with the pointy brass end of the bobbin. The brass tip enables the tapestry to become firmly packed. Enjoy the weight of the bobbin, the feeling and sounds it makes when beating the weft yarns into place on the warps. The bobbins are an extension of my hands and fingers. I use three types; wood with and without brass tips and smaller wooden ones. All of the bobbins I use have been loved and used by other tapestry weavers. Many in my collection were the treasured tools of the tapestry weaver Sara Lindsay who in recent years generously handed them down to me. My voice and ideas are powerfully represented through the medium in tapestry. The texture and density of the fabric embody the themes of fertility, sensitivity and femininity of women’s body and soul.

Instagram: @ema.shin

Shinya Yamamura

Shinya Yamamura, Smoll Box with Egg Shell and Lacqure Powdre Makie : 2016 : Japanese Cypress/Egg Shell/ Lacquer and Gold Powder :71mm×86mm×70mm

a small plane and sculpture sword to shave the wood land.

Kanazawa, Japan

Shinya Yamamura was born in Tokyo in 1960. Inspired by his encounter with urushi or lacquerware at Kanazawa College of Art in Japan, he completed their graduate school program in 1986 and started working as a lacquerware artist. When you hold one of his exquisite small lacquered boxes in your hands and explore its surfaces inside and out, you can immediately appreciate how urushi has come to epitomize the pinnacle of Japanese art, and how such an art form could furnish the exotic image of Japan in the eyes of the rest of the world The breath-taking beauty of his work is an embodiment of the etymological roots of the term urushi itself, an adjective used in old Japanese to mean beauty and sophistication He has held many exhibitions, individually and partnering with other artists, not only throughout Japan but also in New York, Los Angeles, the U.K., France, Finland, South Korea and China, and has received numerous awards. While continuing to create works, he teaches as a professor at Kanazawa College of Art, and is actively engaged in the preservation and popularization of Japanese arts and crafts.

www.facebook.com/shinya.yamamura.10

Instagram: @yamamura_shinya1107

Sheridan Kennedy

Sheridan Kennedy, “Coral Mantis (Tantus scapulus), a native of the New Hybridies”, 2009, Sterling silver, coral, shrimp claws, seed pearls, labradorite; 80mm x 75mm x 220mm; photo: Sheridan Kennedy

Sydney

Sheridan Kennedy, Coral-Mantis-Tantus-scapulus.jpg: The work was made for my post-graduate exhibition The Evolution of Specious. To create the raised bumps in the thin silver armour of the Mantis, and to shape the rolled effect of the metal form, I used my Grandmother’s hammer. I inherited this hammer from her in the early 1980s just as I was beginning my jewellery career. It’s a lady’s hammer – heavy enough to hit a thin nail for hanging pictures or such-like – or for repoussé style texturing of silver ‘armour’. Jeweller’s tools are often shaped to men’s hands, but I like to use this hammer, particularly for more delicate work, because of its lighter weight. While it’s not quite 100 years old it has been around and in use long enough to be on the way to becoming tsukumogami. It’s fitting that it is used to create a creature like the Coral Mantis, which itself aspires to become tsukumogami!

Instagram: @doctor_jewels

Andrea Barker

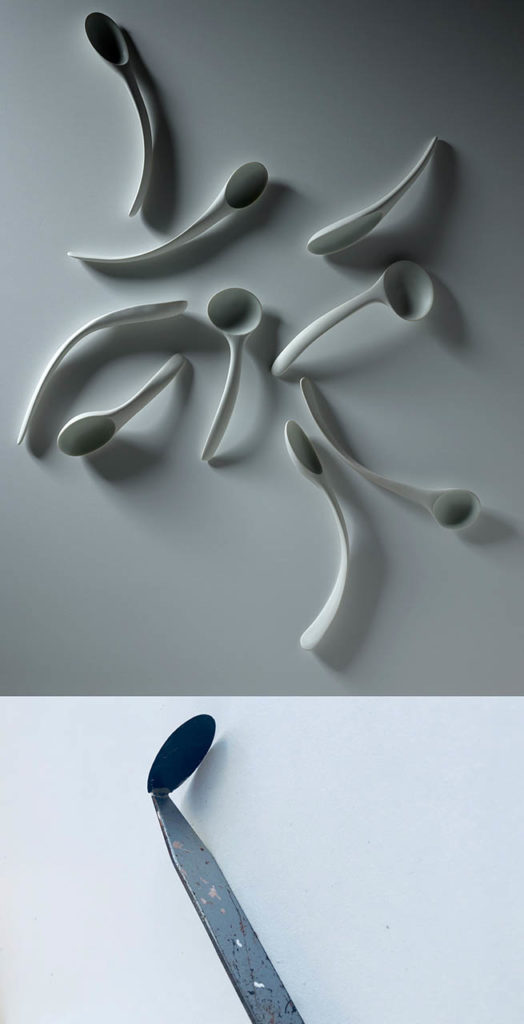

Andrea Barker, Collected Silences, 2014, porcelain, celadon glazes, dimensions variable, photo: Peter Whyte

Hobart, Tasmania

This work is part of a series of spoons I made, as an exploration of ritual and form. Each piece gently blurs the boundaries between sculptural form and functional object as it presents a sense of curve and balance, enclosing space, time, memory and emotion. The porcelain material presents extreme technical challenges to be overcome with the design, manipulation and firing practices of the final pieces absorbed, dissolved and rendered invisible. The intention of these objects is to create a space for contemplation and a sense of tranquility where silence, stillness and restraint abide alongside a notion of simplicity and humility.tool.

This tool was made for me in Seto, on my first trip to Japan in 2001. The material is tungsten, the curve perfectly shaped to scrape dry porcelain into subtle curves. The tool is always sharp, no matter how much I use it, replacing almost all of the other tools I used to use. The material is incredibly strong but strangely brittle and would smash should I ever drop it. It is a pleasure to use, so simple and functional in its design. This tool has now been in my possession for 17 years and is as sharp as the day I bought it. It is an extension of my hand, allowing my gestures to pass easily to the forms I create.

Instagram: @andreabarkerceramics

Mitsuru Yokoyama

Mitsuru Yokoyama, Black Tatami, Natural dyed black igusa, photo: ©Naoyuki_Ogino

Mitsuru Yokoyama, Handmaking Black Tatami, Natural dyed black igusa, traditional sewing materials. photo: ©Yan Kallen

Kyoto, Japan

Black tatami made for the KYOTOGRAPHIE installation. Installed in a main room of the Ryosoukin Temple in Kenninji, Kyoto, Japan. A view of the craftsman and the studio in a collobrative project with photographer Yan Kallen.

Instagram: @yokoyamatatami

Behnaz Barabarian

Behnaz Barabarian, unlocking lock, silver,colorful stones, earing3*2*0/2 ring:3*1.5, photo:Behnaz Barabarian

Made in Iran

I’m a lock which was locked just for once and forever as a sign of eternal of love between two lovers. In all of these years, I stand still on the lover bridge to express loyalty and everlasting love.

Instagram: Behnaz.jewellerystudio

Naoki Sakai

Kanazawa city, Ishikawa, JAPAN

These are welding hammers.

Instagram: @chefnaokichi