Christus Nóbrega journeyed his ancestral homeland in Brazil and found local lacemakers to help recover his family history.

Christus Nóbrega describes the lacemaking tradition of Chã dos Pereira:

The tradition of the Labyrinth lace arrived in Brazil brought by the Portuguese. In Brazil, one of the villages that keeps this tradition alive is Chã dos Pereira, a small village where my grandmother was born. Many ladies are dedicated to lace activity. However, due to the low-income market and the young generations’ lack of interest in crafts, tradition is disappearing.

Income production in Brazil has similarities with that of Portugal. But there are also many differences. However, in both scenarios, we see a decline in the number of women who are dedicated to this craft. Industrial manufacturing is a great competition. That is why it is very important that the government continues to encourage workshops among designers, artists and lace makers so together they can create differentiated artifacts with a different appeal than industrial products.

The transfer of tradition and manufacturing techniques in Chã dos Pereira village (as in others in Brazil) is oral. Young girls learn from their mothers and grandparents.

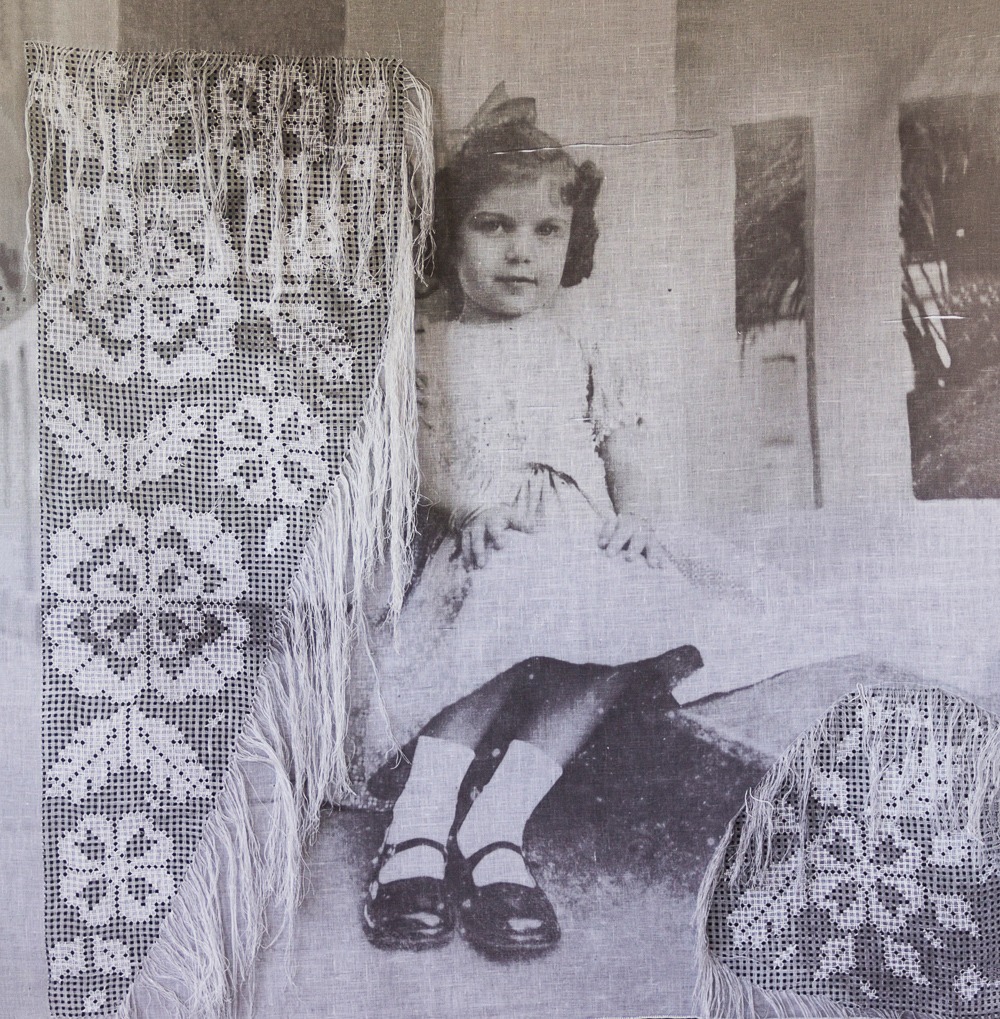

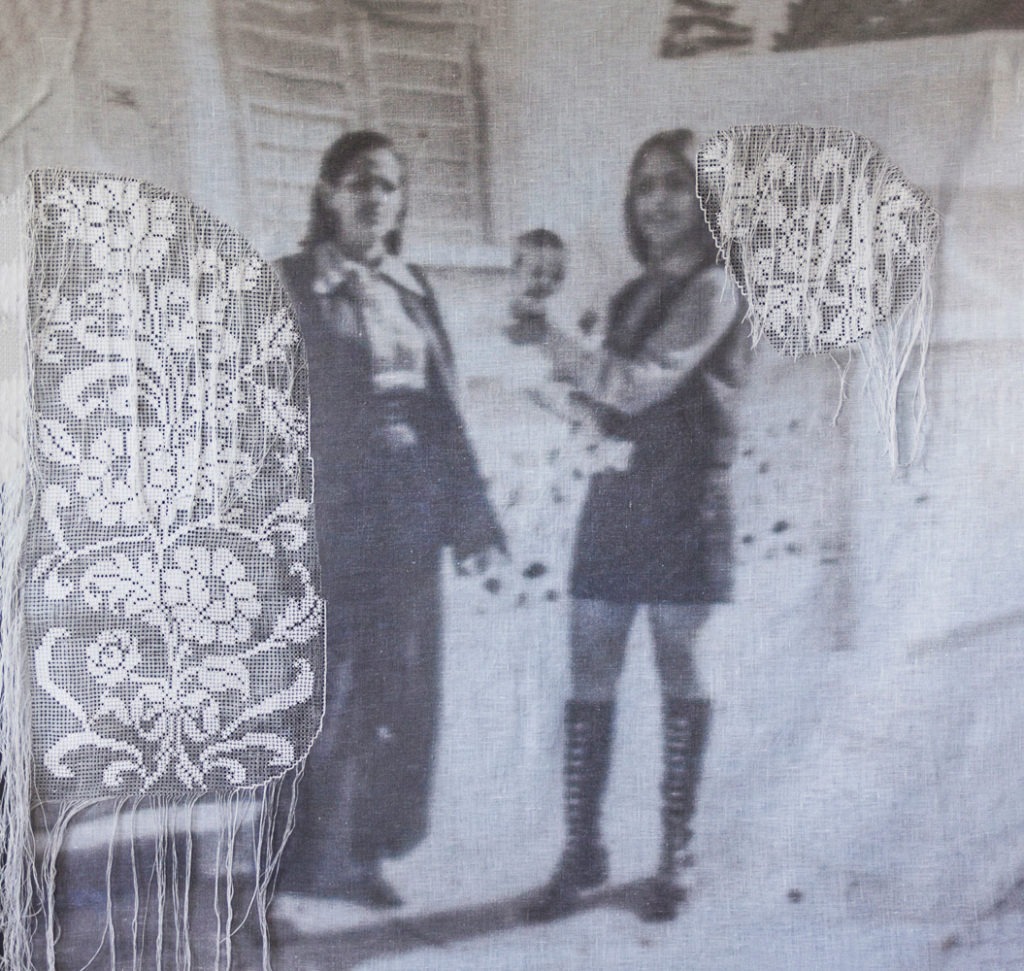

I have a special interest in the history and traditions related to women. In my artwork, I often use these narratives. Working with the lacemakers was a special moment for me. I had the opportunity to learn more about their stories – stories marked by overcoming and strength. Stories that pain and joy – like my grandmother’s story. I tried to leave these stories present in the artwork that I developed with them.

✿

Excerpt from catalogue essay by curator, Cinara Barbosa:

The series titled Labyrinth, which names this exhibition, starts from the development of journeys as an artistic method. It joins other works from a research methodology that Christus calls “travel mythology”. This procedure takes the path to a destination as a reflection of the repertories that it triggers. What do we submit ourselves to while we move? What causes what we’ve been through? What do we find along the way that changes us? The artist also seems interested, in part, in the literary or imagetic (re)interpretation of the theme of the “Wanderer”. As he has already mentioned in previous texts concerning the critical follow-up of this series in particular, the “plot within the weft” (both described by the same word in Portuguese, ‘trama dentro da trama’) is one of the aspects that characterizes the understanding of this production. The artist revisits the family album, the social history of a place and presents works that have the labyrinth lace primarily as a matrix.

Once again, it is highlighted that Christus connects us with another conception of Labyrinth. This type of lace was introduced to Brazil in XVII by European traditions, of which the artist preserves part of the embroidery whilst also interceding for his poetic research. He maintains the linen, which is considered a noble fabric and a symbol of colonial heritage and the cotton economy. It is transformed by stretching the cloth in the rack, as a feature and screen effect. Christus studies and emphasizes the details of the textile fabric and engravings. With this technique, after making the lines of drawing on the fabric, zones are chosen to make the weft from counting and cutting the yarns. With each sequence of three lines, the next three are cut. The motifs, thus, are produced by the shredding, preservation and filling of furrows by wires, and appear above all as the result of emptiness.

In the circumstance of “dismantling” as it mentions, by which the lace is produced, also brings up the story of Chã dos Pereiras. A small district in the municipality of Ingá, 100km from João Pessoa, in his home state of Paraíba. The district is the main producer of Labyrinth lace in the region, almost exclusively by female artisans. In that region, Christus’ grandmother lived, widowed and lost all financial support. She found herself forced to give her six children away to be under the care of distant relatives and religious institutions. Selling lace was one of the few possible resources to keep living. Archeological weaving is necessary to follow the paths formed from there—every old story brings new discoveries.

The art pieces gathered here are the results of three years of coming and going to that region, to the memories and to the experience of a never-ending path. There were regular trips, testing, image collecting, testimonials and exchanges with the labyrinth lacers and family members. The series “Estandartes” (Banners) is part of this exhibition, presented with original material, getting to a total of 30 works. Observing all these pieces it is possible to perceive the paths suggested by the artist and to dare see perspectives from what is exhibited.

Christus Nóbrega – Labirinto, Artisan, 15 February – 28 March 2020 (see interview)