Will Stubbs and Jo Holder write about works that evoke the world around the fibre works by Yolŋu artists in an exhibition at Cross Arts Projects.

Gathul-gärri / Into the Mangroves

Manager of Yirrkala art centre Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, Will Stubbs reflects on life among the mangroves.

This exhibition is an invitation to enter the mangroves. Not to ‘go’ to the mangroves, but to ‘enter’ them.

Words can’t describe the intensity of the sunlight in Arnhem Land. In places like Sydney, the sun hits at a glancing blow, at an angle, but at the Equator, it is a direct hit. The light is so bright it feels like a sound ringing in your ears, drilling through your eyes.

Those eyes are permanently squinted. Your view is always squashed. To try and stop the light from burning a hole in your mind.

And then BANG! You step through a gap in the fringe and the temperature plunges. The clamour of the light is silenced, and you realise you can open your eyes.

At first you are blind. Just like stepping from bright sunlight through the door of a medieval church. Your eyes can’t quite believe what they are seeing. The intricacy of the buttressed shapes arcing away into infinity supports an endless colonnade of pillars. These columns are what is holding up the darkness. . .

In other places, mangrove ‘swamps’ are what cling to the edges of industrial storm drains or dog parks. They are so misused that you can see through the straggle of trees to the built landscape beyond. Where they are thick enough, they are used as rubbish dumps with broken glass and tyres growing in the mud.

In Arnhem Land, however, they are cathedrals: rich smells and the clicking music of hidden life.

Harvesting the fruits of the mangrove is the particular obsession of Yolŋu women. Their knowledge of what lies within and under the trees and the mud is incredible. For, as beautiful as what can be seen is, there is hidden treasure everywhere—for those who can crack the code.

One example only of the hundreds of delicious foods on offer is Dhän’pala. The King, or more likely Queen, of shellfish in East Arnhem, is one that sustains many people and anchors many hunting trips. Found by feeling with feet or combing with hands, knife blades or rakes or sometimes spotted as cryptic lips just poking free of the mud or as a hole or crack in the surface of the mud indicating a subsidence below where she has moved.

It is a fist-sized clam with many names. The typically ugly English common name is ‘Mud Mussel’/Geloina oviformis (with previous scientific names including Gelonia coaxans and Polymesoda erosa). It is also known in Yolŋu matha as Dhäkururru, Räwiya, Rruŋundhaŋaniŋ, Yiwaḻkurr, Yuwaḻkurr and Rägudha. Rägudha means kneecap. This maypal (shellfish) belongs to the Dhuwa half of the world.

The group will emerge from the forest following ancient pathways with hundreds and hundreds of shells in buckets, bags and pockets. And then the feasts will begin.

There is a technique where a small fire is constructed using a specially chosen size and type of kindling around a stacked pyramid of Dhän’pala, so that lighting one match will cook and open as many as thirty at a time.

Hidden aside these treasures are Djiny’djalma or Nyuka, appetisingly named ‘Mud Crabs’ by English speakers. Yolŋu women trek for kilometres atop the network of buttress roots anchoring the mangrove forest in the sweet black mud. There is a rhythm to the mud which a buried mud crab disturbs. Their holes, which are often wedged into hidden sections beneath the trees, are visible only to the trained eye. Then begins the task of extracting the crab with massive vice-like pincers, from their deep dark wet hole—usually with bare hands!

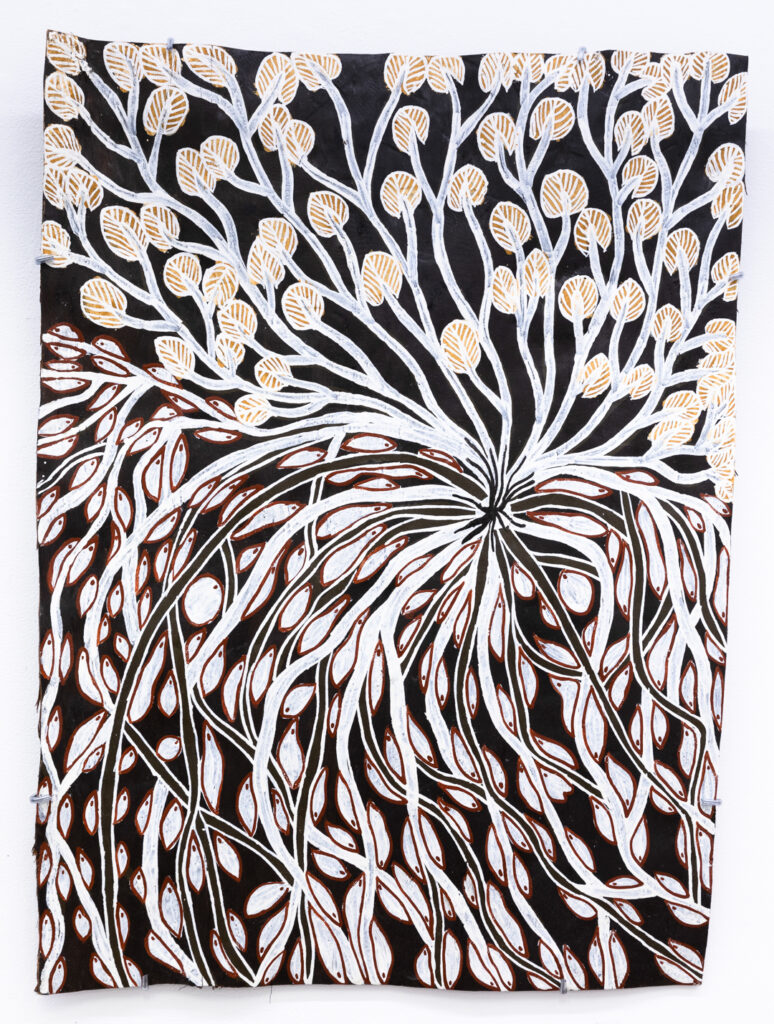

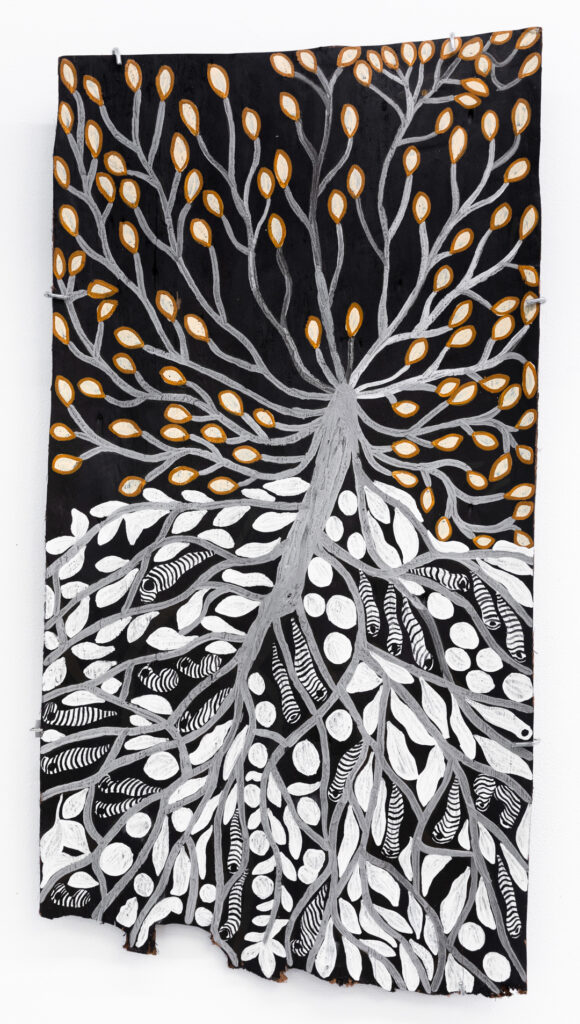

During 2022, Muluymuluy undertook a lot of ceremonial duty in the homelands. When she returned to Yirrkala the bark season had finished. She ended up using offcut boards and embarked on a theme of mangroves. Since then she has continued painting mangroves on bark as well. It should be understood that these paintings are not still lifes. They are an ode to the activity of being within this magic world.

Each work is unique and derives from different themes. From the trees themselves, and their roots and the seeds, to an esoteric reference to the endless list of shellfish which the knowledgeable can find, such as warrapal, dhuṉ’ku or bunybu.

Muluymuluy is the younger sister of famed artist Ms M. Wirrpanda who collaborated with her adopted wawa (or classificatory brother) John Wolseley for over a decade before her death in early 2021. She was a passionate champion of Yolŋu ecological knowledge including a particular interest in illuminating the myriad of edible shellfish found in the waters, beaches, floodplains and mangroves of Arnhem Land. Her poles in this show are a standout example of this genre.

Mangrove Thinking

Curator Jo Holder writes about the concept and work of the exhibition.

The exhibition RISE 3: Mangrove Thinking is part three in a series that flags sea-level rise and the ways that artists think with forms of art to make the ‘invisible’ impacts of climate change visible. Mangroves, seagrass beds and coral reefs work together with tides and currents, rising and falling like lungs. The reefs protect the seagrass beds, mangroves and coasts from strong ocean waves, cyclones and tsunamis.

RISE 3: Mangrove Thinking introduces the art of Muluymuluy Wirrpanda, who is the younger sister of acclaimed artist Ms M. Wirrpanda—a learned and generous mentor for many. The Yolngu sisters are elders of the Dhudi- Djapu clan of the Dhuwa moiety of northeast Arnhem Land. Art by the sisters presents the beauty and fragility of the earth and its ecosystems: here, the interconnection of mangroves with molluscs in the tidal zone. The leaves falling from dense branches circulate nutrients; their art shares the knowledge.

Muluymuluy’s paintings have power and presence: created by a restrained use of the classic oche colours of yellow, white and black within striking compositions that highlight the complex architecture of roots and leaves. Roots form intricate arches, buttresses and tangled cables; counter-balanced by dense branches and canopy. The roots filter nitrates and phosphates from the streams and enable breathing in several ways down to small pneumatophores or snorkel roots.

Ms Wirrpanda was a revolutionary artist and key to many of the most prescient exhibitions of the past decade: the cross-cultural Djalkiri: We are standing on their names – Blue Mud Bay (Nomad, Darwin 2013 and tour including to UTS Gallery Sydney); Ms Wirrpanda and John Wolsley’s Midawarr/Harvest (National Museum of Australia, 2017) and Molluscs / Maypal and the warming of the seas at Geelong Art Gallery, based on James Bentley’s magnificent book for collectors and children: Maypal, Mayali Ga Wänga: Shellfish, Meaning & Place (NAILSMA, 2018). Her works are astoundingly beautiful and painterly.

Coastal cultures depend on mangroves for food, fuel and medicines. Nypa palm fronds are used for thatching and basket weaving. Various barks are used for tanning and curing (trepang for example), and pneumatophores make light rafts for fishing. The wood from yellow mangroves (Ceriops) burns even when wet. Across the north and the archipelago mangrove dyes are used as glorious golden and red colouring for traditional weavings and batik.

In Gamay/Botany Bay, the invading representatives of the British empire dismissed mangrove forests as swampy wastelands. During the First Fleet’s brief stay in 1788, Governor Phillip and some of the officers explored Cook’s River at the NW side of the bay. Lieutenant P.G. King reports, ‘We went up for about 6 miles, finding the Country low & boggy, & no appearance of fresh water…’. Phillip’s journal (chapter VI) complains about ‘dampnefs’ and calls the soil ‘unhealthy’.

Historian Heather Goodall chronicles Sydney’s ambiguous anti-mangrove history: mangroves did not count as ‘bushland’ or as river views but fisherfolk knew the true value. The runways of Sydney Airport now obliterate the estuary of the Cooks River. Sydney’s First Nations people have always pushed back against dispossession and dismissal. Their artists are renowned for making tools, often incised or painted, such as shields, digging sticks, spears and boomerangs from the elbows of branches, especially hard-wood species like the grey mangrove which is also used for boat building. Shell-work was another exchange medium, with artists becoming expert collectors after most middens were burnt for shell lime to build the colony.

Matriarch of the La Perouse community ‘Queen’ Emma Timbery (1842-1916), is famed for her intricate shell work, including heart-shaped ‘forget me not’ boxes and tiny baby booties. Her inspired followers include great grand-daughters Esme Timbery and Rose Timbery and Lola Ryan (1925-2003, Tharawal/Eora). They added temporal images such as the Sydney Harbour Bridge (opened in 1932) and maps of Australia that often subtly invert the status of sparkly ‘curio’ to ownership. Their installations are now heart-pieces of biennales and next-generation lynch-pin public artworks (by artists such as Esme’s daughter Marilyn Russell).

Curated walks and artworks weave carefully around Sydney’s contested and diminished mangrove coastline and the deeper valleys of their estuaries: from the Northern Beaches and Middle Cove to the Badu Mangrove Walk at Sydney Olympic Park where you can recite artist Lorna Munro’s Muru nanga mai/Dreaming Track—a poem etched into the boardwalk as part of Red Room Poetry’s Poetic Moments project.

Mangroves, seagrass and saltmarsh are carbon machines. Blue carbon is a vital global resource for climate resilience, but rapid sea-level rise threatens to drown this valuable ecosystem. At Gamay/Botany Bay, local rangers and conservationists have saved Towra Point Nature Reserve (Ramsar Site, listed 1984) and patches of mangrove and saltmarsh on Cooks River and Wolli Creek Valley. Grey Mangrove shrubs are again conspicuous.

Walk the pathway and think like a mangrove.

RISE 3: Mangrove Thinking is presented by The Cross Art Projects and Buku Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre, 1 — 22 December 2022