Just as the Industrial Revolution sparked the Arts & Crafts Movement, now the AI Revolution is reigniting interest in handcraft as a way of staying human.

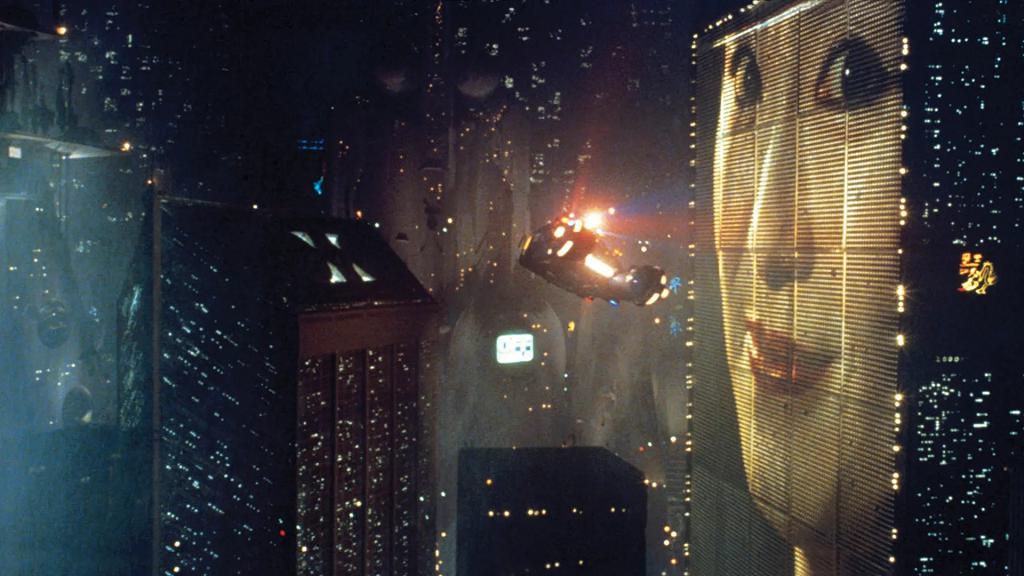

Things were grim, back in the future.

In the 1982 film Blade Runner, the Los Angeles of 2019 is a hell-like space that natural light cannot penetrate. Little is left of nature. Even the pets are artificial. It’s the kind of dystopia we had come to expect of writers imagining our future. In 2025, we can add to that pessimism the “polycrisis” of climate catastrophe, the threat of nuclear war and the takeover of artificial intelligence. Trump’s recent victory will only accelerate all three dangers.

Lately, a silver lining has appeared. For some, these doom-laden scenarios can now be envisaged as a prelude to a revival of humanity. Hopepunk has emerged as an alternative to the dominant “grimdark” genre.

Writers like Becky Chambers imagine a post-apocalyptic utopia. A Psalm for the Wild-Built is based on the premise that intelligent robots reached the conclusion that it was bad for humans to give over so much agency to machines, so they collectively decided to depart from planet Earth, leaving humans to recover their independence. Life in a town called Inkthorn is an example of how humanity was revived through making. Inkthorn is an idyllic community of care, ingenuity and sociality.

Inkthorn’s craftspeople had polished the grain so smooth that from a distance, it looked almost like clay. The village’s practical features were ubiquitous—powered pulleys to bring heavier goods up and down, emergency ladders ready to drop at a moment’s notice, bulbous biogas digesters attached outside kitchen walls—but every home had a unique character, a little whim of the builders.

Of course, we have seen something similar before in the nineteenth-century Arts & Crafts Movement. William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890) imagined a twenty-first-century England that has revived the medieval emphasis on beauty and practical order. The dystopia that writers like Morris were countering was the displacement of human labour by the machine, mainly the industrial loom. As writers like Glenn Adamson observe, our modern value of craft is a reaction against the Industrial Revolution. Without the trauma of industrialisation, many would still consider craft a form of drudgery.

Today, the advent of artificial intelligence is having a similar effect. The sentient machine now can not only weave textiles more efficiently and precisely than humans, but it can also perform many functions that were seen to be the exclusive domain of humans, such as writing, drawing, composing music and driving cars.

But this is where the “shock of the old” emerges again. We’ve seen how the artisanal product has thrived as an attractive alternative to machine-made. Now, we see the prospect of more abstract skills becoming humanised. As discussed at the Knowledge House for Craft, text generated by a human becomes seen as “artisanal” writing. (Here is my misteak to prove this was written by a human).

Knowing that it was written by a human gives it a relational value that the algorithm lacks. With “artisanal writing,” we can develop an understanding of the author and where they are coming from, similar to how we “meet the maker” at a craft market. That is one of the reasons why all the writing in Garland is “authored.” Unlike many other platforms, we don’t re-publish media releases. We want readers to have a connection to the writers.

There is fresh interest in the new claymation of Wallace & Gromit as they refuse to adopt video generation tools and continue to make them by hand.

AI is helping us learn what it is to be human.

One fascinating tussle between humans and machines occurs when we need to verify our humanness on the computer. Previous challenges, such as finding letters or objects in squares, can now be done just as well by AI. The most reliable method now is to monitor the manual actions of the mouse and keyboard. Despite the abstracted world of the screen, work at the computer is still primarily done by hand. The movements of our hands are unpredictable enough that they cannot be imitated by a machine—for the time being, at least.

There is even talk now of a “humanist renaissance”. In her Atlantic article, The Coming Humanist Renaissance, Adrienne LaFrance argues that the saturation of AI-generated culture will lead to a renewed desire for more authentic experiences. Taking this further, Thomas L. Friedman makes a case for the emergence of “stempathy” jobs that embody the kind of emotional intelligence lacking in machines.

But this is not the humanism of the Italian Renaissance, which celebrated Protagoras’ principle that “man is the measure of all things.” The human story is no longer a celebration of “man the maker”, known as homo faber. It is more homo curare, reflecting our unique capacity to care for the world.

This unique emotional connection to the world is described by Meghan O’Gieblyn in her profound response to artificial intelligence, God Human Animal Machine:

Today, as AI continues to blow past us in benchmark after benchmark of higher cognition, we quell our anxiety by insisting that what distinguishes true consciousness is emotions, perception, the ability to experience and feel: the qualities, in other words, that we share with animals.

It’s no surprise that the “care economy” is identified as a significant source of employment growth. The World Economic Forum 2024 paper on the Future of the Care Economy focuses on job creation in response to trends such as an ageing population and the increasing formalisation of predominantly female domestic labour.

However, the care economy is more than a service; it is also a product. The recent Value of Craft Report contains a number of care-full recommendations for craft. This includes the provision of community craft hubs for community strengthening and repair, the recognition of craft therapy not only for rehabilitation but overall well-being and the use of craft in disaster recovery.

Just as craft was a critical response to the Industrial Revolution, the practice of making things by hand will play a key role in the care economy that grows to counter the alienation of artificial intelligence. We see this already with the popularity of evening pottery classes. According to a recent study, the Pottery Ceramics Market was valued at USD 41.20 billion in 2022 and is projected to reach USD 60.90 billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 5.30% from 2024 to 2030.

Julia has taken up pottery classes to cope with a stressful job in the legal sector.

To understand the growing appeal of pottery classes, I spoke with one of the increasing number of office workers who is now learning ceramics. Julia has taken up pottery classes to cope with a stressful job in the legal sector. In her work, Julia represents defendants in the criminal court, which involves long hours, public performance and “a lot of cerebral stuff” working in front of a machine. “My brain is constantly anticipating negatives and imagining the worst.”

She had tried various ways of relaxing during downtime, but they didn’t help with the stress. One day, a friend started taking pottery classes with Belinda Nailon at St Kilda’s Storehouse. Curious to try ceramics for herself, Julia found it “transformative”.

When I’m touching the clay, I’m focusing on this thing in my hands. I’m switching off the brain and just focusing on that piece of clay. I’m creating something from my hands that is very different from everything at work. There’s a lump of clay at the start, and at the end, there’s something else.

Part of the pleasure is the unpredictability of clay. Things might not turn out as you expect, whereas with the machine, everything is the same. You learn to embrace the surprise and the unexpected.

As our work becomes increasingly abstract, producing something material that you can feel in your hands becomes increasingly important. While technology promises to make work more efficient and predictable, making by hand brings life as an unpredictable force back into our world.

We will likely see more people like Julie turn to crafts as work becomes ever more remote, particularly as we interact more with algorithms rather than people. Craft is likely to become an increasingly important service needed by a dehumanised workforce. The challenge for makers is balancing the demand for classes with their own creative needs.

The storm is coming. But hold on. Hope is at hand.

Comments

Such a lot in this article… The place creativity and art making has is a civilised world has been down played for to long…. We need creatives to challenge norms and push boundaries. Art making helps us to think differently and gives time to regain balance in an increasingly high tech world.