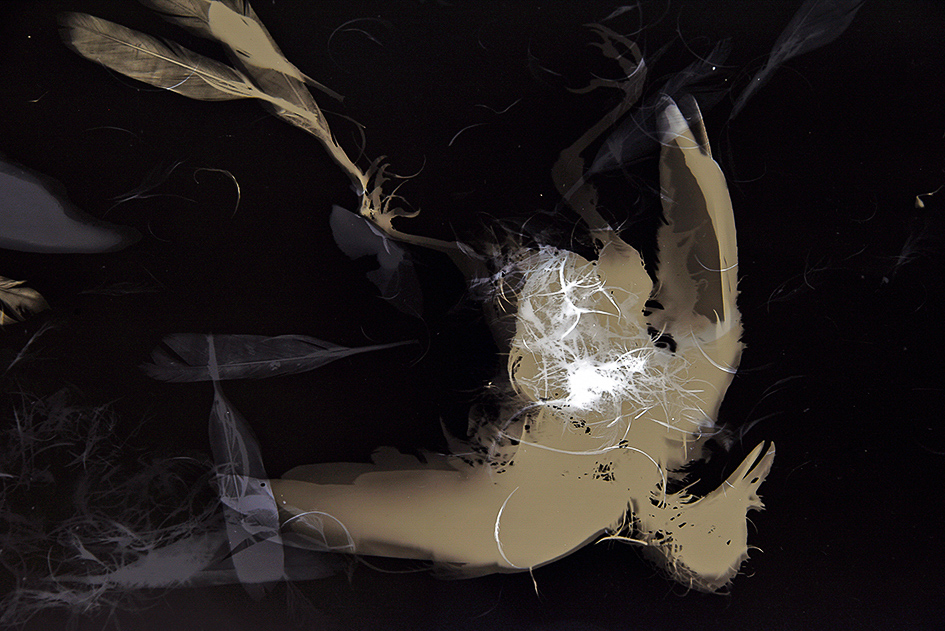

A series of shadowgrams represent the poignant fate of a lone starling, once part of a shimmering murmuration.

Two four-piece and a three-piece set of toned gelatin silver films recording shadows of a Starling’s body, feathers and Cicada husks and garden flowers made without a camera. Each film and film sandwich is encapsulated in a Mylar envelope. Unique objects displayed backlit on lightboxes.

I found the still-warm body of the dead Starling one hot summer afternoon in a suburban Melbourne front yard surrounded by its feathers and cicada remnants. I gathered it all up on a large piece of cardboard carefully maintaining the bird’s mortal gesture and surrounding objects as I found them. In my home darkroom, I placed the bird and other objects on a sheet of gelatin silver photographic film and exposed the film to a pre-calibrated pulse of portable photographic flash-light. I repeated the process several times on fresh sheets of film. I then developed the films in trays. A few days later I went out at night and placed sheets of the same type of film behind the garden vegetation and exposed the films to flash, processing the films the same way. No camera was used. The resulting images are life-scale negative shadows of their subjects: what was opaque or dense in the subject registers as light or transparent on film; where there was little or nothing to block or absorb the light of the flash the film is more exposed and hence darker. I call these camera-less images “shadowgrams”. Three of the Starling images are two sheets overlain and sandwiched together. All the others are single films. The garden images are bluer and slightly denser than the starling images: I bathed the garden films in a selenium chemical toner to create that effect. On the opposite wall is a spotlit inkjet print digitally reiterating the biggest of the film sandwiches as an enlargement on archival rag paper.

The simple analogue technique I employed to make The Fall is in principle the same as I have been using for thirty years although every project has involved the fabrication of special equipment and considerable variation in imaging materials, scale and process.

Introduced by nineteenth-century colonists, the inquisitive, omnivorous, fecund, adaptable Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) lives up to its name driving out and displacing native birds across Australia’s temperate southeast. Yet its wretched exotic status belies an exceptional musical and acrobatic talent. Entranced by its song eighteenth-century composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart kept one as a pet so beloved he commemorated its passing with a funeral service. Why and how clouds of Starlings seamlessly execute the seasonal aerial displays known as ‘murmurations” is a mystery—although each birds awareness of seven neighbours is known to carry through the whole flock, aiding harmonic movement. In ancient Rome, religious augurs divined omens from the shape of their swarmings. Whether or not it fell from a murmuration, the poignant verisimilitude of this little avian corpse can be read as a portent too. Its mortal gesture is reminiscent of renderings of Icarus who flew too close to the sun but the trajectory of change typified by this invasive species invites predictions both more ecological and ominous.

Harry Nankin: The Fall is at Castlemaine Art Museum March 19 – May 2 2021

About Harry Nankin

Photographic artist, educator and environmentalist Harry Nankin is known for his eerily beautiful and poetic use of the revelatory power of simple photographic processes. For three decades he has investigated what he calls the “ecological gaze” using camera-less ‘shadowgrams’ to record environmental phenomena on site. Employing processes that are partly land art, partly performance and partly photography, he has turned the landscape itself into the camera. His subjects have included the sea, rainforest, Mallee woodland, insect colonies, precipitation and capturing the ‘light of the stars’ to render enigmatic pictures of heaven and earth. To interpret the post-goldrush landscapes of central Victoria where he now lives, in 2020 he returned to using the film camera. The recipient of multiple Arts Victoria and Australia Council grants, his artwork has been published, exhibited, reviewed or acquired for collections on four continents.