A dialogue between Madhu Khanna and Christian de Vietri on the subject of his new book Trika Maṇḍala Prakāśa: Illuminating the mandalas of Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka.

Christian de Vietri’s monumental public sculptures and traditional sacred artworks reflect a rare confluence of aesthetic mastery and spiritual inquiry. His works have been exhibited in major museums globally. They are permanently installed in prominent urban locations across Australia, the United States, and China—most notably Spanda, a 100-foot-high sculpture that now stands as a landmark at Elizabeth Quay in Perth. A graduate of the Master of Fine Arts program at Columbia University in 2009, de Vietri was actively engaged in the New York art world before a decisive turn in his life led him toward a deeper engagement with Indic spiritual traditions. In the decade that followed, he undertook immersive study and training with traditional masters of Śākta–Śaiva Tantra and Śilpaśāstra, receiving the requisite initiations and formal authority to carry forward the teachings and practices of these venerable lineages.

I first encountered Christian in New Delhi in 2022, during his visit to the Tantra Foundation Library. It was immediately evident that his artistic vision was not merely informed by Tantric philosophy, but was the living expression of an inner sādhana. His first book, Trika Maṇḍala Prakāśa, which forms the basis of our ensuing dialogue, is a remarkable achievement—at once a scholarly exegesis and a creative resurrection of the five principal maṇḍalas encrypted within the esoteric verses of Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka. This seminal 10th-century treatise, regarded as a crown jewel of Kashmir Śaivism (or the Trika tradition), outlines an integrated vision of metaphysics, ritual, and aesthetics. While its philosophical core has received substantial attention in recent decades, the visual-cum-ritual architecture of its maṇḍalas and their precise method of construction have remained largely obscure.

De Vietri’s pioneering contribution lies in bridging this lacuna. One millennium later, through a process that is simultaneously analytic and contemplative, he has decoded, illustrated, and recontextualised the full suite of Trika maṇḍalas, rendering them once again accessible to the practitioner-scholar. His work exemplifies what we might rightly call Tantric Art in the truest sense—art grounded in the tantras, guided by āgama, transmitted through lineage, and animated by the lived experience of a sādhaka. It is this unique synthesis of the artist, the practitioner, and the scholar that defines his offering to the contemporary world.

How and when did your personal and creative journey unfold?

It is a curious thing to contemplate one’s journey through life. How the road twists and turns, and how suddenly an extraordinary new world can open up that you never even knew existed. On one level, we say: ‘I went here, and I went there’, and yet the spiritual path returns us to that ultimate place of all places within, that which always was and always will be. It’s the great descent of twelve inches from the head to the heart, and paradoxically, we travel the world to find it. But let’s situate all this in time and space.

I was born in a small gold-mining town in the Australian desert, known as Kalgoorlie. It’s not all that different from what you see in the Mad Max films, if you get that reference—flat red earth as far as the eye can see, like the surface of planet Mars, and a four-kilometre-wide stepped hole in the ground for gold excavation, which they call the Superpit. It’s a wild place. In one of my earliest memories, I am making shapes from bits of metal found in the dust. I also vividly remember the first time I saw molten gold being poured, glowing white-hot—a kind of primordial recognition was ignited within me. For as long as I can remember, I have loved creating things. From a young age, I sensed that creating something from nothing connects me with a source that is beyond myself. That feeling of immersion, of communion, and alignment with the force of creativity has always been a great joy and a teacher.

I consider myself extremely fortunate to have parents who encouraged my passion for art. There were always creative projects going on around the home. When I was seven years old, my mother and father took me to the Museum of Modern Art in Nice, France, where the entire array of monochrome cobalt blue Yves Klein artworks was on display. Seeing these fascinating objects, mysteriously interconnected through the colour blue, was profound for me. In an instant, I glimpsed the significance of art throughout the ages, the potential of art, and its eternality, and I knew this is what my life would be about. My interest in art was nurtured by my primary school art teacher Jane Hart and my high school art teacher Michael O’Connell who encouraged me to study fine art at university, which I did in Australia, and then at the National School of Fine Art in Paris, before moving to New York, where I completed a Master of Fine Arts at Columbia University.

After graduating from university, I was having exhibitions of my artwork, mainly sculptures, in galleries and museums around the world, as well as public commissions, and I was active in the New York art scene. Despite external signs of growing professional success, at a certain point, an increasing sense of emptiness and a lack of inner fulfilment began to emerge within me that no amount of money or fame or pleasure could satisfy. I had the creeping sense that I was missing the whole point of existence somehow, and that my role as an artist must be able to serve a higher purpose. So, I turned to yoga. Immediately, light began to stream into my awareness. After several years of dedicated āsana practice, I had the good fortune to meet a young and brilliant tantric scholar–practitioner–teacher named Christopher Wallis, who introduced me to the teachings of Trika Śaivism. It was a pivotal moment, an intense śaktipat descent of grace, a transmission of spiritual energy that was like a subsea earthquake in my psyche, thrusting me urgently and irreversibly onto the path of Self-realisation. My life cracked open to the sacred mystery of being, and all I could do was offer myself up as a servant to the supreme.

Spanda by Christian de Vietri installed in Perth, Western Australia, 2016 (photo courtesy of the artist).

Throughout my thirties, I travelled the world studying with various tantric masters. No single individual today embodies the entirety of the Trika teachings, and so I intuitively embarked on a journey of alchemising multiple vantage points of the tradition. This approach, I later found, is described in the writings of Abhinavagupta, who advises students to seek, like the bee that gathers pollen from many flowers, to then produce their own honey. I wanted to learn from the greatest masters I could find, those to whom I was heart-attracted, and then practice and assimilate what I’d learnt. It was not about finding the loudest voices, but rather the deepest silences in human form. This brought me to Swami Janakānanda in Sweden, who trained me in Kriya and Haṭha Yoga; Swami Śankarānanda in Australia, from whom I received initiation and instruction in Kashmir Śaivism and Jñāna Yoga; Dharmabodhi Sarasvatī in Thailand, who trained me extensively in his vast and unique syncretic system of Trika Mahāsiddha Yoga, which I was subsequently certified to teach; and Mark Dyczkowski, who initiated me with a spiritual name and taught me pure Anuttara Trika over the eight or so years we interacted before his passing. Mark also led me from Varanasi to his own teacher in Bhaktapur, where I studied under the tutelage of the late great Śrī Kedar Raj Rajopadhyaya, revered Nepalese guru of the Kubjikā and broader Sarvāmnāya tradition, who eventually initiated me into the Kaula dispensation. I learnt from several other teachers along the way, but it was not until I was initiated by Paul Muller-Ortega in 2018 that I realised I had found my heart-master, and the pillar practice that would ensure safe passage across the ocean of saṃsāra.

Christian de Vietri with Mark Dyczkowski and photo of Swami Lakshmanjoo at his home in Varanasi, 2016 (photo courtesy of Benjamin Joel Cran).

What sparked your interest in Tantra’s sacred literature and tantric ritual art, and how many years did you take to finish your recent book, Trika Maṇḍala Prakāśa?

Well, I started off as a practitioner. As my mind and body transformed from tantric practice, I was naturally inclined towards studying sacred texts and developing a synergy between my experience and my knowledge of the tradition. I also desired to understand what role art plays in the process of liberation, and how, as an artist, I could be of service. My artwork began to move into alignment with the spiritual path. During my time at Swami Janakānanda’s ashram in Sweden back in 2014, he told me with great tenderness once about a moment as a youth sitting on the roof of his master Satyananda’s ashram in Bihar, when he decided to give up his former life as an artist to pursue the path of a sannyasi. I knew I was at a similar juncture myself, but I had no intention of completely renouncing worldly life; I wanted to find a way to honour and transmute the creative spirit that burns so brightly inside me and redirect that energy towards embodied enlightenment in the world. That afternoon, in Janakānanda’s library, I discovered your incredible book Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity and Ajit Mookerjee’s epic tome Tantra Art. These books were the gateway to a new world for me, opening my eyes to the possibility and the necessity of tantric art. I realised I had to find a teacher, and this led me first to Nepal, where I studied the traditional painting of yantras and the sculpting of deities with several master craftsmen. My search for the source of authentic Indian Art and Architecture continued, and I eventually found my Vāstu guru Jessie Mercay and Śilpa gurus Ponni Selvanathan and Sthapati Selvanathan, who have been training me in the wisdom and practice of their South Indian Viśvakarmā lineage for the last eight years. So, there have been these parallel, intertwining channels of investigation for me: on one hand, tantric study with spiritual practice, and on the other, tantric art based in Śilpaśāstra (the science of artistic creation). In creating the recent book Trika Maṇḍala Prakāśa, my spiritual and creative life finally fused into one. It took two years of total dedication to complete, but the seed and content of the book had already been growing for more than ten years.

Your book Trika Maṇḍala Prakāśa is a profound artistic and philosophical work that provides the first comprehensive visuo-textual illumination of all Trika maṇḍalas from Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka. To introduce the topic for those less familiar with it, maybe you could provide a brief answer to a complex question: What is a maṇḍala?

For each tantric tradition, its maṇḍala is the most important visual form. It serves as a geometric substrate for ritual practice, but it also encodes, contains, and conveys spiritual teachings. Perhaps in simplest terms, we could say that the maṇḍala is your ultimate ‘Selfie’, with a capital S. Nowadays, it has become quite acceptable for people to perform the strange act of taking a picture of their own face by holding their phone camera at arm’s length, and then concretely affirming, ‘Look, this is me’ or ‘Here “I” am’. In contrast, the maṇḍala says no, that is just your body, which is indeed beautiful and precious and useful, but one day that will dissolve into dust. The maṇḍala invites its viewer to recognise that the real you, the true Self, is much more than that. You are the one eternal, unbounded consciousness at the very centre of the maṇḍala, the bindu point around which the entire manifest world turns. Through line and form and colour, the maṇḍala reflects back our fundamental identity in the mirror of our true Self. Maṇḍalas lead to the eternal ground of being, and yet they are all differently designed because there are multiple paths to attaining embodied self-realisation. A maṇḍala is then transformative in the sense that through visual perception it reconfigures the assemblage point and inner matrix of our individual identity.

If we analyse the Sanskrit etymology of the word maṇḍala, it provides a key to understanding its true significance. This semantic method, known as nirvacana, is a well-established hermeneutic practice in the Sanskrit tradition, serving as a means of accessing and elucidating the deeper meaning of a particular term. Let’s take a closer look. Within the word maṇḍala we have maṇḍa and la. Maṇḍa in Sanskrit means the spirituous part of a liquor, or the creamy part of milk, or the frothy foam head of a beer. It is the ‘essence’ of something, the pith. The verbal root la means to encompass, to receive, and to bestow. So, a maṇḍala is therefore pure congealed consciousness, and it is ‘that which bestows essence’. By unpacking the word in this way, and then putting it back together again, we recover its most elevated, essential, esoteric implication. The maṇḍala encompasses and conveys the truth of reality because it is a direct expression of that reality in material form. In other words, the inherent pattern of consciousness rises to its own surface as the maṇḍala, like the curds of whey, and through this solidified form we can visibly apprehend and experience the essence core of our very own consciousness.

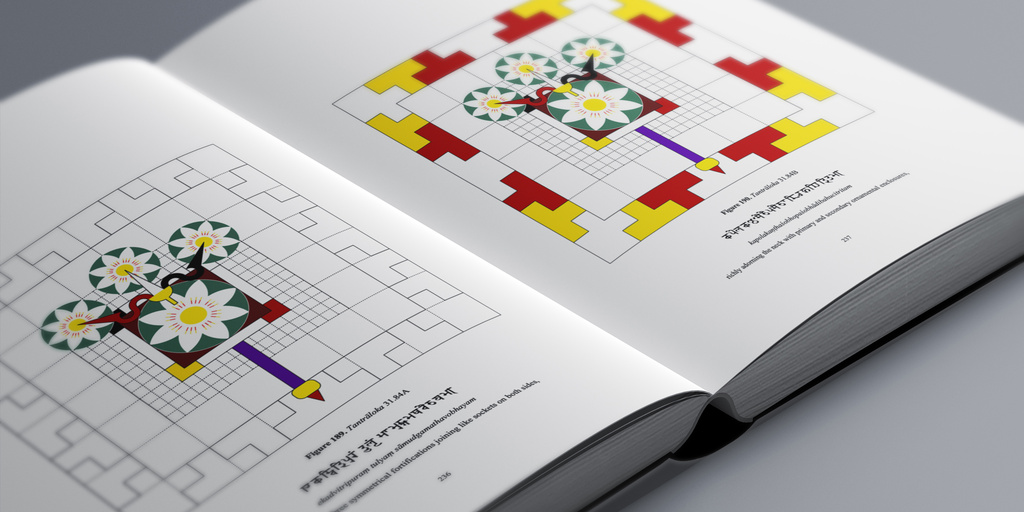

As an icon and a tool, the maṇḍala is an absolutely crucial, irreplaceable component of a tantric tradition. Listeners will likely be familiar with the famous and beautiful śrīcakra, for example, with its mesmerising interlocking triangles, which is the central maṇḍala of the Śrividyā tradition, and has made its way, for better or worse, onto the walls of yoga studios everywhere in the world. And yet, for our Trika tradition, until now, the complete set of its unique maṇḍalas, precisely rendered and coloured, has not been seen. And so that is what I set out to do with this book: to bring the Trika maṇḍalas to life. The book includes the full construction sequence of five different maṇḍalas, described by the great master Abhinavagupta in Chapters 29 and 31 of his Tantrāloka, which correspond to four levels of development in Trika practice: entry level, senior level, advanced level, and finally, there is a most exquisite maṇḍala for appointing a new guru of the tradition. The images in the book reveal the hidden essence of these maṇḍalas, which is encoded within the original text and made lucidly visible for the first time.

The book Trika Maṇḍala Prakāśa (2024) by Christian de Vietri, p.236–237 (photo courtesy of the artist).

The book combines the scholarly study of the Trika śāstra from Kashmir and illustrates the yantras, cakras, and maṇḍalas used for exoteric and esoteric worship. On one hand, there are hard-core literary descriptions from primary Sanskrit sources; on the other, their translations are in visual form with mathematical precision. Could you elaborate on your challenges as an artist in integrating these two disciplines in one volume?

Yes, engaging fully with the Trika maṇḍalas required multiple layers of work. First, there was the translation of Abhinavagupta’s primary text from Sanskrit into English, which was a challenging task in and of itself, given the complexity of the verses. My main focus was Chapter 31 of the Tantrāloka, which is completely dedicated to the maṇḍalas, and the important Kula maṇḍala from Chapter 29. All the verses that describe these maṇdalas are highly technical and semantically encoded. So, in addition to the basic translation, there was a compound process of deciphering that had to take place. For example, a verse might say, ‘Within the base of the trident, between the two platforms, is an aṅgula measure equal to the ocean of sky’. This, firstly, has to be understood within the context of multiple cumulative instructions that evolve over fifty or so verses to finally generate a complete form. Then there are technical nuances to interpret, such as where the platform is, how much is an aṅgula, and what is the ocean of sky? To elaborate a little further on this example, ‘platform’ here refers to the upper and lower sections of a vertical form, a kind of pedestal being articulated within the maṇḍala. The term aṅgula refers to a specific length in the ancient Indian measuring system used by traditional artists. The term ‘ocean of sky’ is derived from the Sanskrit words khā and abdhi. Because khā refers to the tenth mansion in Vedic astrology, and because there are classically four oceans (abdhi), the combination of these two terms as khābdhi signifies the number 40 (10 × 4). So, you can see how it’s not just a matter of translating individual words or sentences but also figuring out specific technical meanings within the context of maṇḍala creation. Furthermore, neither the translation nor the decoding could be done accurately without actually drawing what the text seeks to convey in its specific verse-by-verse sequence. These three levels of translating, decoding and illustrating had to happen simultaneously, each one being cross-checked by the two others until they all aligned. At any given time, I would have the Sanskrit text of the Tantrāloka open along with the Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary, multiple digital dictionaries, my Word document, the drawing software, and a sketchpad. It was an intensely demanding process, a whole-brain, whole-being kind of task. If I made a mistake on one part of the maṇḍala, or if a word wasn’t quite right, the entire sequence of images had to shift and be reworked, and I did that several times over. In drawing, I had to be completely faithful to what the text seeks to convey. The foundation of the artistic side of the work was my knowledge and experience of Śilpaśāstra—in particular its unique measuring system. I then developed my own visual grammar for drawing the instructions with lines of different shades and types, as well as a particular labelling method. But it’s important to note that the maṇḍala forms themselves are not my invention per se; they were supposedly in use one thousand years ago at the time of Abhinavagupta, and so every single word in Chapter 31 of the Tantrāloka is an exact and unalterable instruction to create the maṇḍalas, along with Abhinavagupta’s curatorial vision. It’s incredible how each entire maṇḍala is so economically encoded in textual form, with such superb minimalism and brevity of expression. The maṇḍalas are densely packed into these short verses, so this whole endeavour of revealing them in the book was like carefully unfolding a palace from inside a purse.

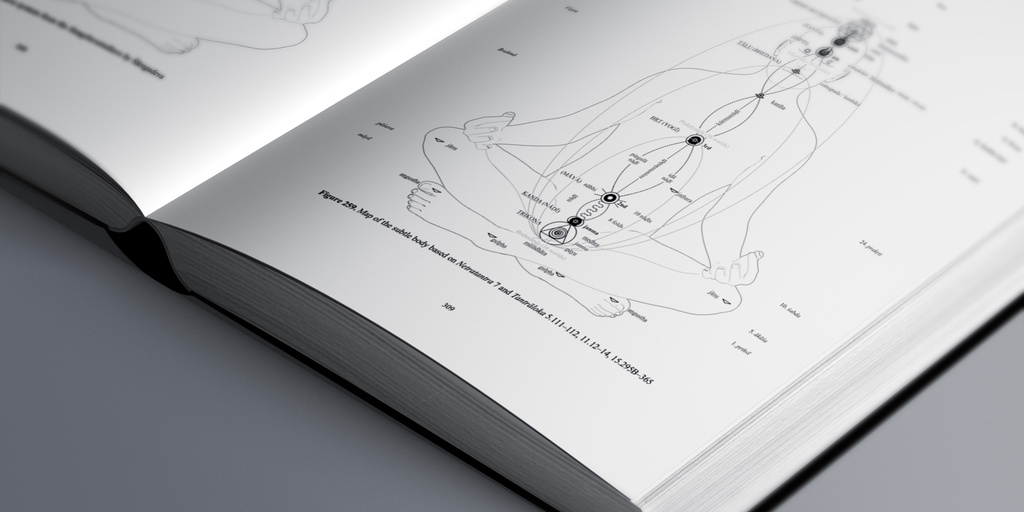

The book Trika Maṇḍala Prakāśa (2024) by Christian de Vietri, p.310–311 (photo courtesy of the artist).

There is a tension between the śāstra (authoritative literary text) and prayoga, their ritual application in tantric practice. Textual descriptions are coded and do not reveal all the details. Many elements of the figures are decoded and learnt from the living practitioners and gurus of the sampradāyas. Could you share some experiences of how these authentic religious specialists, practitioners, scholars or gurus contributed to your research and helped bridge the gap between the text and its prayoga aspect?

It’s such an important point that you raise. The instructions in Chapter 31 of the Tantrāloka primarily consist of quotations from other texts, written in the prescriptive optative mode (the potential mood) of Sanskrit. Meaning to say that, for the most part, the reader is being told how something ought to take place for the desired results. The step-by-step construction of the maṇḍalas is described in detail, providing all the necessary information one would need to create the form; however, there is limited information provided regarding the precise techniques for practically performing the actual construction. This would indicate that the text serves as a guide for the guru, and that the actual creator of the maṇḍala, whether that be the guru or an artist employed by the guru, would likely have another, even more detailed set of instructions, a sub-paddhati, in addition to the requisite training and certification for carrying out the task, just as the manual for a car does not teach you how to drive the car nor does it give you a drivers’ license. And this concurs with my own experience of tantric initiation and training as a śilpin—that these fine details must be learnt, in person, from teacher to disciple, artist to artist. There are also certain topics that I had to articulate with great care to preserve vows of secrecy that I have undertaken through initiation. What I’ve done with the book is to consciously tread that very fine line, giving as much information as I am permitted to publicly, while acknowledging that aspects of the practice still have to be learnt privately from a qualified teacher in order to be performed.

Here, I’m talking only about the creation of the maṇḍala. In addition to creating the maṇḍala, there is also the question of what practices are done with the maṇḍala and how to perform those practices, which require a separate set of instructions. This brings us to another significant issue, the act of revealing the otherwise concealed maṇḍala, which itself is considered a form of initiation. The Trident Lotus Maṇḍala, for example, is for the first level of initiation into the Trika. Once the guru has agreed to initiate the disciple, they are led blindfolded into a room where the maṇḍala is beautifully laid out on the floor and seen for the first time. This maṇḍala, when installed to scale, functions like a compact two-dimensional temple laid out as a multi-coloured floor plan. Upon entering the maṇḍala structure through its gate, the disciple circumambulates its inner sanctum, and there the tantric practice, specifically the mantra, is communicated to the disciple by the teacher. There is a lot more to it than that; I’m simplifying, but my point is that there is an important ontological and functional distinction between the illustrations in the book and the actual maṇḍala made with coloured materials for the initiation ritual. In the case of another maṇḍala, the Kula maṇḍala, which I dedicate a whole chapter to in the book, the initiatory mantra is conveyed at the end of an elaborate ritual using small lamps placed in specific locations that spell out its phonetic structure for the disciple. These are, of course, secret practices, not performed publicly and not widely known. We must remember that these maṇḍalas serve a very high and specific purpose—they operate as catalysts within a system of spiritual practice that is designed to lead an aspirant to jīvanmukti, the state of liberation while still alive.

The book Trika Maṇḍala Prakāśa (2024) by Christian de Vietri, p.308-309 (photo courtesy of the artist).

Regarding your question about the individuals who contributed to my research, there were many. A discussion of the Trika maṇḍalas cannot be complete without first mentioning the ground-breaking work of Alexis Sanderson, particularly his seminal essay from 1986, ‘Maṇḍala and Āgamic Identity in the Trika of Kashmir’, in which he proposes line drawings of two maṇḍalas from the Tantrāloka. And for those who don’t know, we should mention that you completed your PhD that same year at Oxford, Madhu, under Sanderson’s supervision, on the concept and liturgy of the śrīcakra, which remains a definitive and unsurpassed study of this important yantra and its worship within the Śrīvidyā tradition. There is a rigour and a love in that dissertation, which was moving for me to encounter, and a perspective that can only come from the mind and heart of a truly adept scholar–practitioner. I would add that the high level of academic and artistic integrity exhibited by Judit Törzsök in her approach to the maṇḍalas she investigates in her essay ‘Icons of Inclusivism’ was a source of inspiration for me as well and helped to shape my own approach to writing about the delicate work of decoding the Trika maṇḍalas. In a sense, I built upon and expanded her methodological example by explaining my process and reasoning alongside the visual forms of the maṇḍalas I deciphered.

My gurus, Paul Muller-Ortega and Mark Dyczkowski, have contributed greatly to my overall understanding of the Tantrāloka and Abhinavagupta’s exegetical arguments, which allowed me to appropriately situate the work of illustrating the maṇḍalas within the larger view of the Trika tradition. This proved crucial in bringing to light how these sacred forms are relevant and applicable for practitioners today. In addition, learning from the esteemed Kashmiri guru Śrī Pran Nath Kaul, a direct disciple of Swami Lakshmanjoo, helped in forming my understanding of Trika practice as it currently exists in Kashmir. When it came to figuring out the fine details of the maṇḍala designs and their meanings, my interactions with Kṛṣṇan Nambūdiripad and Vikas Nīlakandhan Enghakkattu from Kerala were indispensable. These two gurus taught me how multiple levels of esoteric teachings are encoded within maṇḍalas through colour and form, which is so profound, so beautiful.

The Indian/Hindu colour palette is distinctive. For example, yellow is taken from turmeric, blue from evening clouds, red from hibiscus flowers, and so forth. Can you tell us something about how this unique colour palette is used in your work and its significance in understanding the patterning of forms, which is a means of accessing a variety of symbols?

The goal in selecting the colours within each maṇḍala image in the book was to get as close as possible to the colour of the materials that would be used when installing the maṇḍala for worship. I provide an extensive table that details all the correspondences between colours and choices of material. White, for example, might be rice, or pearl, or bone. Black could be charred grain, black cat’s eye gemstone, or charcoal from a cremation ground. All the materials would be powdered and applied to specific segments of the maṇḍala, but there are various options prescribed according to the means of the practitioner and the desired outcome of the practice. Generally speaking, materials that are safe and easily procured are considered conducive to liberation, whereas the shock value of more transgressive materials like blood and bone is traditionally chosen for the accelerated activation of specific attainments. Just as the materiality can change, so too can the signification of each colour. In the art of maṇḍala creation, colour is always meaningful, but it is multivalent, not fixed, and so a particular colour will convey different teachings according to how and where it is used.

As you said, it’s a very distinctive colour palette, rich in symbolism. In Western ideas about colour, we have this notion that the full spectrum of colours can be created from the three primary pigments: red, yellow, and blue. We also have the device-dependent system of red, green, and blue used for digital computer screens and so on. As useful as they are as ways of conceptualising and using colour, these systems only apply to what the human eye can perceive. The Indian sacred arts are not so concerned with what can be mixed and matched on the surface level of reality, which is understood to be relatively obvious. The Indian system of colour signification that we see in the maṇḍalas, for example, encompasses both the seen and unseen, the manifest and the unmanifest, and its colour codes express, through hue, how the formless comes into form. It considers the mechanics of that process, and colour then serves like a mapping device for reverse-engineering consciousness, such that through art, one may return to source.

The journey of pure colourless consciousness as it pulsates between transcendence and immanence, and coagulates into the sattvic, rajasic, and tamasic states, could be understood as being like the transformation of water from vapour to liquid to ice, and the colours corresponding to those states of increasing densification of consciousness are white, red, and black. These are not primary colours in the Western understanding, but rather primordial qualities that constitute the underlying trajectory of creation. The concept of creation in this context is not something out there in a past time separate from us, but rather a process that continually and spontaneously arises through the perceiver, from consciousness, which is simultaneously one and many, singular and shared. So, these three colours, white, red, and black, can generally be seen in the outer perimeter of the maṇḍala, connecting the internal with the external.

The five elements—earth, water, fire, wind, and space—which are like the building blocks of reality, are also encoded in different ways within the maṇḍala as white, yellow, red, green, and black (or transparent or dark blue), respectively, and there are reasons for each of these associations. For example, the wind element in the maṇḍala is green because it will be composed of crushed leaves, and it is the trees and plants of the earth, which are immobile, grounded, that provide the sustenance for all the other mobile organisms to exercise movement, the essence of the wind element. And so, colour in this instance is seen as a form of empowering nourishment, offered and digested through the sense of sight via the maṇḍala. No choice of colour is random or unconsidered in this schema, and everything has its place, its origin, and its meaning, its use value.

As a case in point, the last maṇḍala in the book, the so-called Sky-Lord Svastika Maṇḍala, which is designed for the appointment of a new guru, is a remarkable design in which the full spectrum of colours seems to gloriously explode out from the centre. Each cardinal direction of the structure is associated with a different deity, each having its own colour-coded attribute or weapon. The final exquisite verse describing that maṇḍala tells us, ‘This is where the gods of gods abide, granting the fruit of all desire’.

What problems did you face in making accurate textual translations before rendering them in illustrations?

My primary task of translating the text was constantly being tested as I attempted to simultaneously draw what was being described. In this way, the illustrations and translations refined one another as the work progressed. I don’t think I could have arrived at accurate translations without the external illumination and verification that my imaging of the verses provided. So many of the verses could only be understood by seeing them and checking them within the context of the maṇḍala and its process of creation.

Jayaratha’s twelfth-century commentary on the Tantrāloka, of course, helps us immensely to understand the text. For example, a brief few lines from him about the Kula Maṇḍala in Chapter 29 provide the key to understanding how exactly that maṇḍala is created, without which it would remain quite obscure. But even with his commentary, the verses are still extremely enigmatic upon first read.

At the end of each sequence of maṇḍala configurations, I provide a series of notes that function somewhat like a traditional commentary that reveals my process of interpretation and the challenges I faced, although my focus there is less on the grammatical aspect of Sanskrit translation and more on exposing my artistic decision-making. I still have pages and pages of word-by-word breakdowns of my textual translations that I did not include in the book, in favour of maintaining focus on the visual solutions I arrived at to illustrate the maṇḍalas. You see, I wanted to do something different with this book. The primacy of the text, which scholars customarily foreground in their work on the tantric traditions, is here flipped and backgrounded, such that the mystical vision of the Trika maṇḍalas is given centre stage as the primary plane of communication, as it is in the actual process of initiation into the Trika.

One of the hardest parts of the text to translate, and subsequently to draw, was the centre of the Triple Trident Maṇḍala. I revised my translation and illustration of that section multiple times before it conclusively clicked together. Abhinavagupta prescribes this most powerful maṇḍala as the visual gateway for the highest level of initiation into the Anuttara Trika. It is a truly astonishing design in which a seamless agamic fusion of Trika, Kaula, and Krama doctrines is elegantly expressed in visual form through a complex and multilayered fusion of tridents, voids, and lotuses. Moving towards the centre of this maṇḍala, the practitioner journeys from common Trika practice with three Goddesses, to the esoteric heart of secret Krama practice where the highest fourth Goddess resides on the pericarp of the central lotus and encompasses them all. Working on this part of the design was like entering the reactor core of a powerplant, the nuclear fission-point of the maṇḍala, that most subtle and potent place of division where the one becomes many, where formlessness becomes form. Rendering it in words and images was an extremely delicate operation, just as terrifying as it was thrilling. Waves of tears flowed through me when my transfigured cognition of this maṇḍala finally synced and visually settled into place. It felt like a direct initiation into the heart of reality from the Goddess herself. It is no wonder that Abhinavagupta exalts this maṇḍala as the most supreme and auspicious channel to Self-realisation, first and foremost amongst the maṇḍalas of Chapter 31.

An introduction to the key elements of the Trika tradition prefaces the figures, and reading it, one is struck by the rigour of the scholarly explanations. Here, one sees another incarnation of Christian de Vietri?

Previously, I mentioned those three levels of work that took place: translation, decoding, and illustration. What you are speaking of here is the fourth meta-level in which I framed the work textually in terms of its history, philosophy, and functionality. This includes both the introduction before the sequence of images, as well as an extensive section afterwards dedicated to the practical application of the maṇḍalas. You see, at a certain point while translating and drawing, I realised that the potency of what was being unveiled could be lost or abused without the appropriate contextual framework for understanding and eventually applying it all. This fourth level was probably the most difficult aspect of the whole endeavour, because it is the sensitive interstitial zone where sacred text and sacred art meet the world. If the first three levels were the food preparation, cooking, and plating, the fourth step was the act of mindfully serving up and presenting the ingredients for contemporary consumption and posterity. Honestly, I was tempted to present the illustrations by themselves, but it would have been a bit like giving someone raw meat for dinner. I followed through with this fourth meta-framing level from a sense of responsibility to the artwork and to the reader. I hope to have done justice to these divine forms, for the benefit of those who encounter them.

The book significantly contributes to the study of sacred ritual and meditational maṇḍalas. It underscores that a textual analysis of the Tantric ritual would remain incomplete without the visual illustrations that support it, thereby emphasising the crucial role of art and the integral quality of words and images. Thank you for sharing your research. Your book is a valuable contribution to the field, and we are grateful for your efforts.

Thank you for your careful engagement with my book, Madhu. Your insightful questions have brought out new angles to the work that I think will be valuable to share. It’s been a pleasure and honour to speak with you.

For more information about Christian de Vietri and his work, please visit his website: www.christiandevietri.com. The book Trika Maṇḍala Prakāśa can be purchased internationally through Amazon.com

This interview is printed in Malini Journal (New Delhi: Ishwar Ashram Trust, 2025) vol. XVII no. 4

About Madhu Khanna

Madhu Khanna is an Indian scholar specialising in Tantric studies, with a particular focus on Goddess-centric Śākta traditions. Based in Delhi, she is the Tagore National Fellow at the National Museum and the Director and founding trustee of the Tantra Foundation. Khanna earned her D.Phil. in Indology from the University of Oxford in 1986, under the supervision of Professor Alexis Sanderson. Her doctoral thesis, The Concept and Liturgy of the Śricakra Based on Śivānanda’s Trilogy, laid the groundwork for a lifetime of engagement with Hindu Tantra. She has authored and edited numerous influential works, including Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity (1994); The Tantric Way: Art, Science, Ritual (with Ajit Mookerjee); and Studies on Tantra in Bengal and Eastern India (2023). Khanna has held significant academic positions, notably as the former Director of the Centre for the Study of Comparative Religion and Civilizations at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. She has also served as Associate Professor at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), where she led interdisciplinary projects such as Prakriti: Man in Harmony with the Elements and Rta: Cosmic Order & Chaos. Her scholarly contributions have earned her multiple accolades, including the Sarasvati Ratna Abhisekha (2000), the Mahavir Mahatma Award (2005) and, most recently in 2024, she won the Oxford Bookstore Art Book Prize for her publication Tantra on the Edge, which examines the work of K.C.S. Paniker, S.H. Raza and Gogi Saroj Pal, among others, and explores about the impact of Tantra on modern Indian art. Visit thetantrafoundationlibrary.com

Madhu Khanna is an Indian scholar specialising in Tantric studies, with a particular focus on Goddess-centric Śākta traditions. Based in Delhi, she is the Tagore National Fellow at the National Museum and the Director and founding trustee of the Tantra Foundation. Khanna earned her D.Phil. in Indology from the University of Oxford in 1986, under the supervision of Professor Alexis Sanderson. Her doctoral thesis, The Concept and Liturgy of the Śricakra Based on Śivānanda’s Trilogy, laid the groundwork for a lifetime of engagement with Hindu Tantra. She has authored and edited numerous influential works, including Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity (1994); The Tantric Way: Art, Science, Ritual (with Ajit Mookerjee); and Studies on Tantra in Bengal and Eastern India (2023). Khanna has held significant academic positions, notably as the former Director of the Centre for the Study of Comparative Religion and Civilizations at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. She has also served as Associate Professor at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), where she led interdisciplinary projects such as Prakriti: Man in Harmony with the Elements and Rta: Cosmic Order & Chaos. Her scholarly contributions have earned her multiple accolades, including the Sarasvati Ratna Abhisekha (2000), the Mahavir Mahatma Award (2005) and, most recently in 2024, she won the Oxford Bookstore Art Book Prize for her publication Tantra on the Edge, which examines the work of K.C.S. Paniker, S.H. Raza and Gogi Saroj Pal, among others, and explores about the impact of Tantra on modern Indian art. Visit thetantrafoundationlibrary.com