For Jacqueline Millner, Jacqueline Rose’s paper collages humanise geometry and enliven space

Playful and experimental, subtle and minimal, Jacqueline Rose’s works on paper are finely honed evocations of time and place and testament to the enduring language of geometric abstraction. They are grounded in a strong sense of art historical context and in long-nurtured erudition in a range of artforms — including literature, music, dance and architecture — which sustain Rose in her creative practice. To this sound base, the artist brings continuous, attentive improvisation. Her process balances meticulous mark-making with an openness to change, producing compositions conducive both to meandering imagining and meditative stillness.

Geometric abstraction, which conventional art history tells us emerged in the wake of Cubism not long into the twentieth century, is generally understood as comprising a purely pictorial reality built from elemental geometric forms. Despite often betraying the physicality of materials, given its debt to collage, it became renowned for its “flatness” or “alloverness” and is considered a crucial precursor to the abstraction that rose to ascendancy mid-century with its claims to transcendental, universal values. These discourses have been thoroughly taken to task, including by feminist perspectives that insist on embodied positionality, but the language of geometric abstraction endures to remind us of counter-currents which reductive histories may have covered over.

Paul Klee, for example, understood abstract drawing as an expression of relations with natural forms and animal instincts, including playful engagements with poetry, literature, and music as his whimsical titles often suggest. Klee saw drawing as intimately tied to the moving body, especially to the embodied practices of writing and walking, and in being so performative, hence intimately tied also to time. In his pedagogic writing while a teacher at the Bauhaus, Klee proposed that drawing is “time-bound” in its creation and reception, as both are governed by the capacities of the human body. During the time-bound process of making, the artist either adds or subtracts; the viewer then “grazes” over the surface, “grasping sharply portion after portion, to convey them to the brain which collects and stores the impressions. The eye travels along the paths cut out for it in the work”.

- Jacqueline Rose, Intervals #4, Pencil and collage on paper, 70 x100 cm

- Jacqueline Rose, Intervals #3, 2020, Etching and collage on paper, 80 x 105 cm

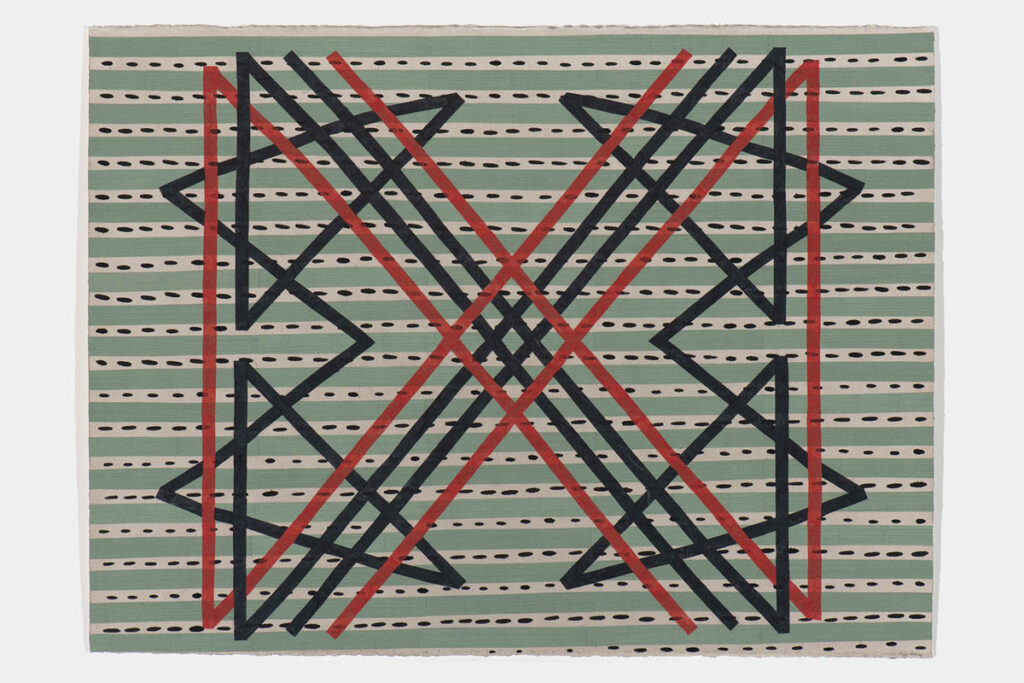

- Jacqueline Rose, Enigmagnetic #4, 2020, Ink and collage on paper, 56 x 76 cm

Rose performs a series of actions that accumulate routes of mark-making across a carefully prepared plane; these actions then “cut a path” for the viewer to enter, to follow or digress from, as they move through a corresponding series of comprehensions. Rose begins with the plane: in recent works, neutral-coloured handmade papers with their own assertive materiality. Working with this matter, Rose overlays washes, brushstrokes, or pencil, crayon and ink marks, open to how each medium yields or resists. This then becomes the substrate for collage, often comprising of coloured paper strips, a material that lends itself to playful improvisation while maintaining the sharp, rigorous lines distinctive to the artist’s work. At each point of the process, Rose is alive to rhythm and pause, possibility and obstacle, improvising in response to light, materials, bodily sensation and deeply embodied knowledge, as well as duration. The results are subtly pulsating images that oscillate between abstract figure and ground, their energy flowing through circuits, grids and cycles.

The intricacy of design and meticulous execution renders the duration of the artist’s process palpable in the work, beckoning the viewer to reciprocate by spending time. Scale also plays a part: Rose’s drawings are not large and installed in such a way as to create the possibility for a more intimate exchange, a more reflective experience, positioned as if inviting touch and pause. While not site-specific as such, they key into the memory traces still embedded in this unique space from its many years as a local library’s reading room, and gently riff off the glints of blue that enter through the generous bay-facing windows.

The hand remains our principal method of transcribing and documenting sensory stimuli

The works’ apparent formal simplicity comes from a multitude of creative decisions that balance colour, line and texture, a layering that at times resembles stitching. Through this reference to craft, Rose foregrounds the embodied nature of thinking, the process of continual exchange between the senses and the brain in which the hand as sensor plays a crucial role. The hand remains our principal method of transcribing and documenting sensory stimuli, a vital medium for processing impressions into thoughts. The labours of making, like stitching and drawing, underline that we come to new ways of thinking as our body traces out connections: our conceptualising is inextricable from the physical act of doing.

A “truly abstract line”, write Deleuze and Guattari, is neither self-referential nor essential. It is “…a line that delimits nothing, that describes no contour, that no longer goes from one point to another but instead passes between points, that is always declining from the horizontal and the vertical and deviating from the diagonal, that is constantly changing directions, a mutant…that is without outside or inside, form or background…”. Such a conception might serve to unburden geometric abstraction from the weight of an art history that located its concerns primarily in the transcendental, the spiritual, the essential, and in discourses of painting about painting. Such a conception might enliven the embodied materiality of the line and its capacity to focus our attention on the here and now: this might be the subtle work of Rose’s drawings.

Jacqueline Millner is a widely published arts writer and Professor of Visual Arts, La Trobe University, Melbourne.

Jacqueline Rose, Woollahra Gallery at Redleaf, 30 November 2022 to 8 January 2023.