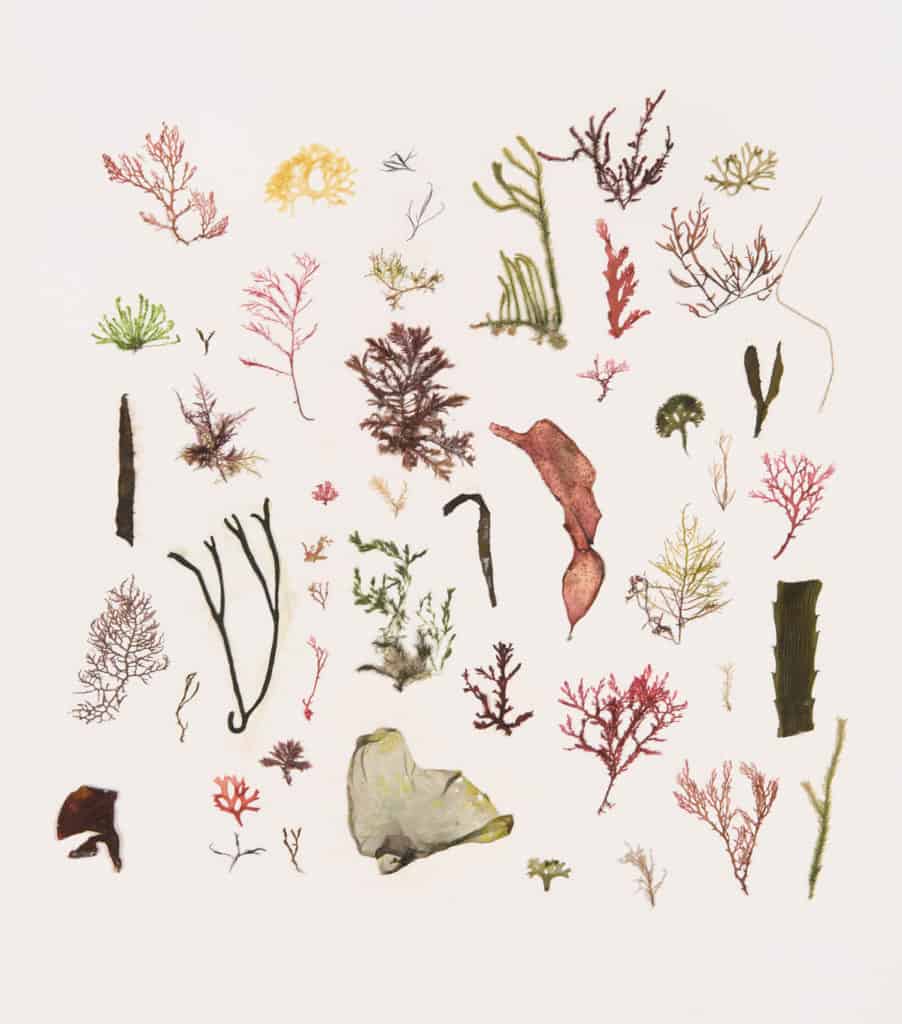

- Julie Ryder, Hortus seccus I, 2019, Arches paper, marine macroalgae, 70cm x 60cm, Dorian Photography

- Julie Ryder , Sampler, 2019, metal sieve, wood, cotton and linen embroidery, natural and indigo dyes, 90 x 50cm, Dorian Photography

Canberra textile artist Julie Ryder shares her series of beautiful works that reveal the subterfuge of sea plants and parallel hidden place of women in scientific history.

The Hidden Sex is a solo exhibition inspired by my 2016 arts residency at the National Museum of Australia. My initial project was to research their botanical holdings to inspire a new body of work, and I quickly became obsessed with two unprovenanced Australian marine macroalgae (seaweed) albums in their collection. Both dated from the nineteenth century and had been bought at auction several years prior. The first album contained seaweeds collected from Port Arthur in 1836, with several pages of dried mosses towards the back. The second album was even more intriguing. It contained over 200 pressed seaweeds predominantly from Port Philip Bay in Victoria, but also from the Cape of Good Hope and Ireland between 1854 and 1880s. Although it seemed unlikely at the time, my passion for detective mysteries and research enabled me to discover the creators of these albums towards the end of my residency—but that, as they say, is another story! This experience, however, focussed my attention on Australian women seaweed collectors of the nineteenth century, and thus The Hidden Sex was born. The title of the exhibition refers not only to these women collectors but also to the fact that seaweeds are a class of plant known as Cryptogams, plants that reproduce by spores, not flowers or seeds. The Latin word Cryptogamae literally means “hidden marriage” or “hidden sex”.

This exhibition highlights the invisibility of women in both society and science in the nineteenth century. Women were not allowed to attend university and were rarely if ever, recognised for their contribution to our knowledge of our Australian flora, and in particular our marine macroalgae. The kudos usually went to men, such as Government Botanist, Ferdinand von Mueller; William Henry Harvey, the great Irish phycologist; Joseph Hooker, of Kew; and Carl Agardh of Sweden. Few know that Mueller conscripted over 225 women and children to collect for him, and some of these women sent their collections directly overseas to other scientists. Hence the botanical collections by some of our most prolific women collectors, such as Jessie Hussey of Encounter Bay, SA; Louisa Ann Meredith and Susan Fereday from Tasmania, are also represented internationally.

Julie Ryder, Collecting Ladies1, Detail, 2017, watercolour, marine macro algae, pricking, 80x60cm, Dorian Photography

Women of the nineteenth century had prescribed pastimes to help them while away the hours—botanical collection and watercolour painting, needlework, music and languages. In the mid-nineteenth century, the craze for collecting seaweed was at its height, having taken over from fern collecting, or pteridomania. Botanical collections were pressed in special albums, on cards and in books, and became the subject of watercolours and dioramas. The series of three works on paper in my exhibition, Collecting Ladies, references the pastimes of lace-making, embroidery and botanical collecting, by combining watercolours with dried pressed seaweeds to mimic hand-stitching.

Julie Ryder, From land and sea – Rhodospermae, Chlorospermae, Melanospermae, 2019, vintage kid gloves, embroidery, pressed seaweed, each pair 45cm x 10cm, Julie Ryder

The challenging geographical conditions to which women botanical collectors were subjected caused me to reflect on the restrictive fashions of the time. In the mid-1800s, women were required to conform to rigid dress standards both inside the home and out. Corsets, bodices, crinolines, petticoats, bustles, gloves, hats, parasols, boots and hose seem like over-kill for a stroll on the beach, let alone suitable attire for collecting seaweed amongst the crashing waves. I was particularly interested in the variety of gloves that graced the hands of all but the very poor. Gloves were made in supple yet tight-fitting leather so that they could mould the hand into the prescribed shape—dainty, with long tapering fingers; not flaccid, yet not too muscular. They also kept the skin unblemished from the sun. These gloves could not get wet, so there is a paradox between wearing the gloves and the act of nature collecting. In From Land and Sea, I have hand-embroidered three pairs of vintage kid leather gloves with representations of the three classes of seaweed as classified by William Harvey in the nineteenth century: Rhodospermae (red); Chlorospermae (green) and Melanospermae (brown). The seaweeds snake up the fingers to the top of the elbow, swirling around the forearm as though trapped in the very act of collection.

Julie Ryder, Submerged, 2019, vintage lace handkerchiefs, cyanotype, 150 x 150cm, photo: Julie Ryder

One of the most recognisable names amongst women botanical collectors of the time was the British seaweed enthusiast, Anna Atkins. She pioneered the cyanotype process invented by a family friend, Sir John Herschel, using the technique to produce handmade albums of over 400 British seaweeds that she had collected and identified. Using the same technique, I immersed 42 vintage lace handkerchiefs into the light-sensitive emulsion, and, once dry, exposed them to different species of seaweed I had collected during my research. This body of work, Submerged, pays homage to Anna Atkins and refers to both the algae being submerged under the waves as well as the status of women in nineteenth-century academia and science. The installation of these delicate lace-edged and embroidered textiles emphasised the colour variation inherent in the blue and white process, evoking the ebb and flow of the tides on the littoral zone.

- Julie Ryder, Flowers Of The Sea, 2019, glass, digital print, etching, marine macroalgae, silicon, each75 x 25cm, Dorian Photography

- Julie Ryder, Ocean’s Gay Flowers, 2019, Fabbriano paper, cyanotype, each 40 x 56cm, photo: Julie Ryder

This process is developed on watercolour paper in Call us not Weeds and Ocean’s Gay Flowers and is reminiscent of Atkins’s approach to specimens as a collector and taxonomist. Enlarged images of seaweeds collected from six specific locations in Australia and Ireland were chosen to correspond to a series of works on glass entitled Flowers of the Sea. These six large glass panels (each 75 x 25cm) reference the decorative Victorian glass microscope slides that were prepared for scientists by specialist companies. Printed papers that were the trademark of each company covered the surface of the glass except for the circular area where the specimen would be mounted. I have digitally printed Victorian lace designs onto my glass slides and engraved them with the place of the collection (Orford, Encounter Bay, Ballinskelligs, Frank’s Beach, MacMaster’s Beach and Bicheno). Some of these locations relate directly to our past women seaweed collectors, whilst others are favourite collection sites that have personal resonance. Seaweeds collected at each location were then dried, pressed and permanently mounted into the centre by affixing with a “coverslip” of glass.

- Julie Ryder, Hortus Conclusus, 2019, cuttlefish, carving, 200x200cm, 5ft photography

- Julie Ryder, Hortus Conclusus, detail, 2019, cuttlefish, carbing, 200x200cm, 5ft photography

Lastly, as an avid collector of anything that the waves throw up, I have made a large wall installation Hortus conclusus (which literally means hidden, secret or walled garden). Made entirely from cuttlebones, these have been collected over a period of years and reference the aggressive passion for collecting multiples of everything by scientists and amateur scientists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, even to the extinction of the species. In my collection, there are two “types” of cuttlebones that can be found: smooth ones, and furrowed ones, which are very labial in appearance. These are not known to be “male” and “female” types. In fact, conversations with marine biologists have not shed any light as to why there are two sorts. As they are NOT seaweeds I was wondering whether they belonged in the exhibition at all, despite their obvious evocation of hidden female genitalia.

During the course of my research, I discovered an unusual feature of the Australian cuttlefish that ensured its addition to the exhibition. During the annual mating season, the cuttlefish gather en masse in Whyalla, SA, for an orgy. Well, not really an orgy, because males only mate once, and then they die. As there are more males than females, competition to hand her their “sperm sac” (yes literally, with their tentacles, as opposed to copulation) is fierce, with the larger, more dominant males guarding the females from other weaker males. However, these “inferior” males have come up with a unique and very sneaky strategy to sidle up to the females in order to hand over their genes. They camouflage themselves as females, even to the point of having a fake egg sac, so that they can mingle with the females unobtrusively to avoid fighting with the stronger male. Ingenious. Hidden Sex…..

Julie Ryder

‘The Hidden Sex’ was exhibited at Craft ACT from 31 January – 16 March 2019. Julie Ryder wishes to acknowledge the Australia Council for the Arts and artsACT for funding the NMA and Cill Rialaig residencies for this project.