Installation view, ‘the churchie emerging art prize 2022’, Institute of Modern Art. In view: Kevin Diallo, Ode To Zouglou (from left to right: Zigbo, Au Maquis, Mouho, Botcho), 2021, Acrylic paint on pigment printed cotton canvas, 90 x 63 cm each, photo: Joe Ruckli

Claire Grant talks to Kevin Diallo about the vivid imprints of his journey from Cote d’Ivoire in the churchie emerging art prize.

Smiling figures dance and gyrate, move and sway across my screen. I don’t fully understand what I’m seeing, and I definitely can’t understand what they’re singing about in French, but I like it.

A quick google search produces hundreds of Zouglou music videos on YouTube, with a top hit by Magic System recording over 12 million views. This niche musical genre was developed during the late 1990s in the West African nation of Côte d’Ivoire. Artist Kevin Diallo joins me from there via video chat, after recently relocating back to his childhood home from Sydney.

We meet on a sunny Sunday morning in Abidjan, and a balmy spring evening in Brisbane. Our distance in time and space is reduced to insignificance by the power of technology. The internet’s capacity to bridge physical separation has proven a vital link during relentless years of lockdowns and border closures.

“I was stuck home [in Sydney]; the borders were shut, my son was born, and no one in my family had seen him. I was thinking about the worst case scenario: What if we’re in lockdown forever, how do you transmit culture? And at the time we were starting to think about coming back here [to Cote d’Ivoire]. I was really melancholic of the place and starting to listen to a lot of music from my childhood. [Listening to] songs and looking on YouTube and people commenting “Who’s still listening to this in 2020?!” and I’m like “Yeah!”. All this stuff from the nineties … I just went down the memory hole.”

Diallo’s Ode to Zouglou (2020) emerged during this period of longing and separation from home, a symptom of his digital diaspora. The four-panel textile work recently gained a Commendation Prize at The Churchie Emerging Art Prize 2022. Judge Sebastian Goldspink commented: “Diallo’s practice displays a tension between the analogue and the digital”.

This material tension is evident in the glittering hand-painted geometric stripes that adorn a soft wash of digitally printed human forms – screenshots snapped from YouTube Zouglou dance clips. Shimmering vertical patterns inspired by traditional West African mud cloth designs are layered over the blurred and ambiguous dancing figures. Their pixelated details coalesce when viewed from a distance. The criss-crossed configuration of the canvas panels echoes the glittering designs, forming an alluring textural combination of old and new media. They reveal a cultural reconnection to Diallo’s Ivory Coast roots, rekindled over the internet during the pandemic.

While looking through Diallo’s previous works I noticed his 2019 solo exhibition titled Blue also features dancing. I ask if it’s a recurrent motif in his work.

“You know, it’s funny because you don’t actually realise themes in your work until you start building a body of work; then certain things always come back quite naturally. I feel like for me it’s often water and dancing, but talking about blackness [in these contexts].”

Blue was developed during an intrepid voyage from San Diego to Sydney after Diallo took up the offer to accompany three friends on their small sailing yacht. I’ve lived on boats and barges in previous careers, so our conversation briefly diverts to tall tales of sharks and sea voyages before veering back to art. The installation for Blue featured a video projection on white sailcloth of a shirtless Diallo at sea: headphones in, dancing, relaxed.

“I have always been fascinated by the ocean. I grew up quite close to the coast and the history of black people and the ocean struck a chord … a lot of black bodies have crossed the ocean for suffering… I had a ritual where I was taking photos and videos of the sunset every day … So every sunset I was sitting on the deck, strapping my camera to the boat recording … And then I had this idea of doing the dance on the deck as a performance piece.”

We discuss how Kevin’s work as a news cameraman connects to the narrative of black people dying at sea, continued today in the tragic coverage of migrants fleeing across the Mediterranean. “I’m really uneasy with this narrative of suffering. There are success stories that I don’t think we hear too much about.” On his personal experience at sea, he says:

“With my luck and my privilege, I start dancing on a really expensive boat and I’m crossing an ocean with three of my friends. I was really reclaiming a bit [of the narrative], and it’s also how far we’ve come … it’s not falling into a stereotype … [it’s] playing with the codes of the representation of black bodies on the water.”

Accompanying Diallo’s dancing self-portrait, a looped video of his sunset recording rituals evocatively titled Did my brothers enjoy the sunset? (2019) references his Caribbean heritage:

“My mum is from Martinique. I grew up in Africa but my mum is Caribbean, so [I’m] a direct descendant of slaves on my mother’s side. I very much grew up with this Caribbean side where slavery was talked about and that Martinique is still a French colony, with all that comes with it. During the middle passage one of the things to keep the slaves fit, they would bring the slaves to deck and ask them to dance. For me I was reappropriating this fact that people went on deck to dance for the master’s amusement, but also to keep fit so that they wouldn’t arrive in America or the Caribbean completely weak.”

Diallo interrogates the seemingly pleasant, pacific image of a beautiful sunset at sea from the perspective of “thinking about people that cross the ocean, people that were suffering. Do you actually enjoy beauty? Do you have time to stop if you’re in distress? So I was playing on this repeated sunset, imagining how people at sea would have experienced it. How does your privilege influence your way to experience the sunset?”

Alongside his video work, Diallo has delved into various alternative processes. Informed by his studies in Photography and Situated Media at UTS, and his work as a fashion photographer and news cameraman, Diallo’s practice merges this digital sensibility with historic photographic techniques.

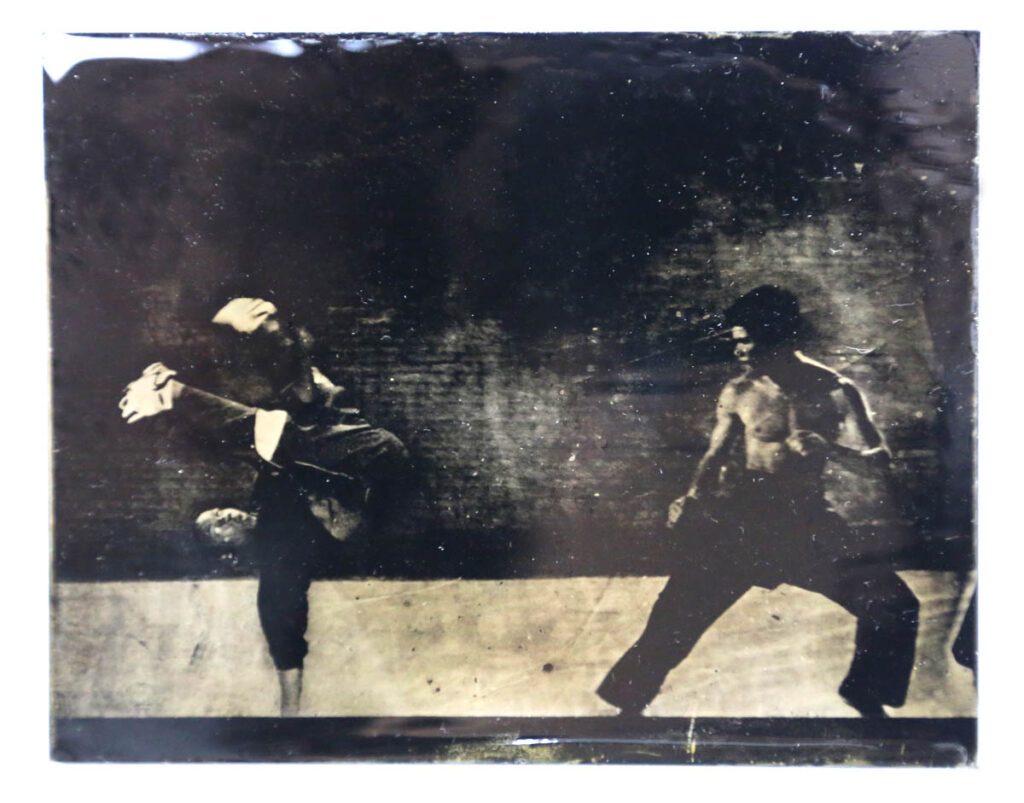

Kevin Diallo, The Anatomy of Choreography (Plate 1), 2019, Tintype, 10.16cm x 12.7cm, photo: Kevin Diallo

A series of wet-plate collodion contact-prints titled The anatomy of choreography (2019) featured in the collaborative venture Unleash the Dragon with fellow artist Zoe Wong, exploring cross-cultural appreciation vs appropriation. The collodion plates show scenes of Kung-Fu masters and Hip-Hop dancers placed side by side in a digitised combat pastiche. Diallo says of these:

“That was the whole exploration of photography when I stopped thinking that I needed to take photos to make work, that I could use found images. I had this thing about process, because I really enjoy analogue processes… I could start collaging something in Photoshop or glitching things and reprint it as an original print; it becomes a photograph. So it’s playing with what’s reality and what’s photography… then you can start creating realities that you would like to see and challenge the status quo.”

This self-described “hacker mentality”, incorporating collage and found imagery into his practice, also led Diallo to his use of cyanotype.

“I started printing a lot on wax fabric. I embed cyanotype emulsion into the wax fabric and then I make prints on it… There’s an interesting story about wax fabric. The Dutch, when they colonised Indonesia, or tried to colonise Indonesia, they stole batik and went back to Holland and started producing en masse and trying to sell it to the Indonesians. And it didn’t work… [so] they brought those fabrics to West Africa. People started using it and called it African fabric. But it’s a Dutch product which has been appropriated by Africans. The first artist that I’ve seen really clearly explain it to audiences is called Yinka Shonibare. He’s a Nigerian British artist…he uses wax fabric to talk about colonialism and how this fabric is called African fabric but it’s actually made in Europe. What does it tell you about our trade, and what’s left from colonialism? Even the way that we dress has been given to us by Westerners.’

Kevin Diallo, You Can’t Tell a Black Man Not To Wear Jordans, 2020, Painted Cyanotype on Original Dutch Wax Fabric, 57cm x 97.5cm

Bright, bold, and provocative. Kevin Diallo’s practice challenges institutionalised signifiers of Black and African identity by deftly deconstructing embedded visual codes. Employing history and autobiography to create photographic collages and multimedia installations that tell a different story, his work summons a positive new future.

However, if you’re in the mood for a virtual throwback to the past, simply type “retro Zouglou” into your search bar to enjoy a nostalgic taste of the late nineties Ivory Coast. Dancing is recommended.

Kevin Diallo is a finalist and commendation prize winner in The Churchie Emerging Art Prize 2022 at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane from 30 July – 1 October 2022. He is represented by Aster and Asha Gallery. Visit kevdiallo.com.

About Claire Grant

Originally from Aotearoa New Zealand, Claire Grant currently lives in Meanjin (Brisbane). She is a freelance arts writer and visual artist with a passion for works on paper, particularly experimental and alternative photography. She studied Fine Arts majoring in Photography at the University of Canterbury and Museum Studies at the University of Queensland and regularly exhibits her artwork around Australia. Visit www.clairegrantart.com and follow @_loudandclaire_

Originally from Aotearoa New Zealand, Claire Grant currently lives in Meanjin (Brisbane). She is a freelance arts writer and visual artist with a passion for works on paper, particularly experimental and alternative photography. She studied Fine Arts majoring in Photography at the University of Canterbury and Museum Studies at the University of Queensland and regularly exhibits her artwork around Australia. Visit www.clairegrantart.com and follow @_loudandclaire_