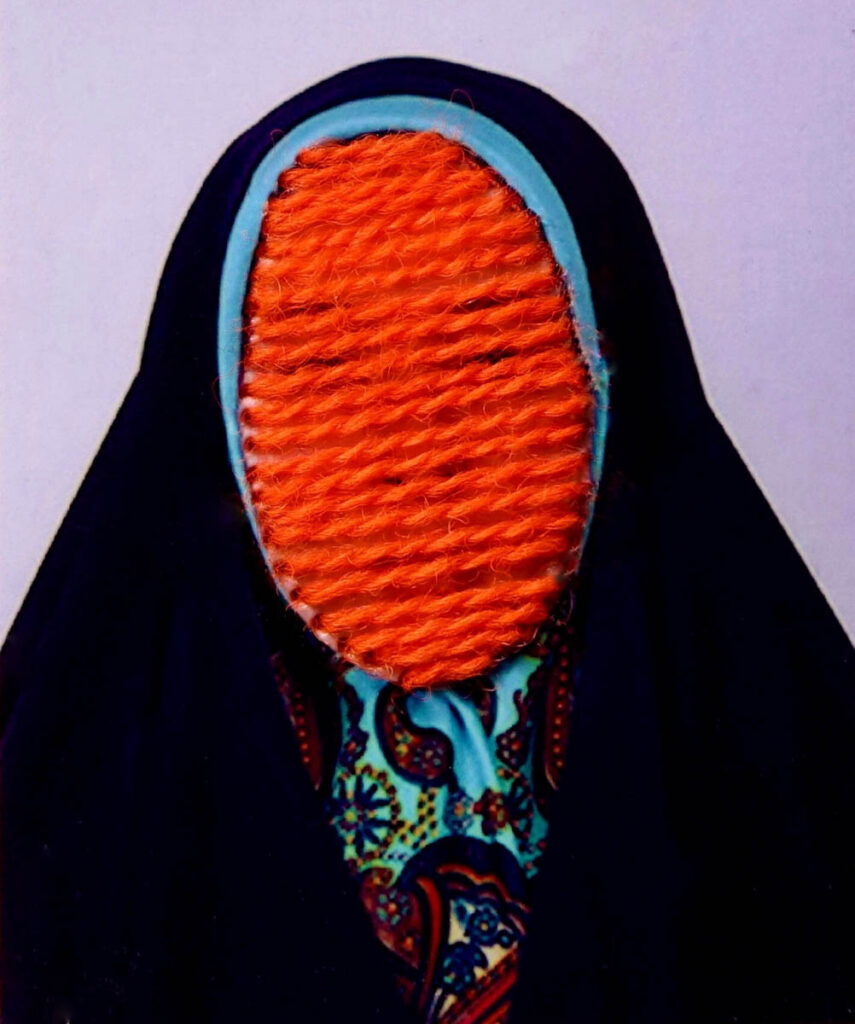

Latifa Zafar Attaii, One Thousand Individuals, 2021/22, Passport photographies, 3 cm x 4 cm each, embroidery, wood, color; Commissioned by Verein Treibsand, Courtesy of the artist; photo: Chantal Romani

Susann Wintsch writes about Latifa Zafar Attaii’s embroidered photographs that reflect the fraught identity of Hazara refugees.

“No one knew better than [Karel] Čapek that the cultivation of soil and cultivation of spirit are connatural, and not merely analogical, activities. What holds true for the soil—that you must give it more than you take away—also holds true for nations, institutions, marriage, friendship, education, in short for human culture as a whole, which comes into being and maintains itself in time only as long as its cultivators over-give of themselves. Gardening for Čapek is an education in the self-imparting generosity on which life in all its basic forms depends (and human culture is but one of these forms, albeit an expansive one). “

Robert Pogue Harrison Gardens, An Essay on the Human Condition

A thousand people look us straight in the eye. Their tiny portraits, copies of passport photos, are arranged in twelve rows along a grid. Yet we cannot return these thousand gazes, for the artist has embroidered over each face by hand, using thin wool thread. Nor can we see exactly what the person behind the threads looks like. Some of the threads are bright and sunny, while others are gray, midnight-blue, or dark green. It’s not clear why one person is given rose-colored or neon-yellow glasses while someone else’s view is massively obscured. What is certain is that this is about more than the specific individual.

- Latifa Zafar Attaii, One Thousand Individuals, 2021/22, Passport photographies, 3 cm x 4 cm each, embroidery, wood, color; Commissioned by Verein Treibsand, Courtesy of the artist; photo: Chantal Romani

- Latifa Zafar Attaii, One Thousand Individuals, 2021/22, Passport photographies, 3 cm x 4 cm each, embroidery, wood, color; Commissioned by Verein Treibsand, Courtesy of the artist; photo: Chantal Romani

In many parts of the world, clothing is embroidered to protect the wearer against the evil eye. What we cannot know is that the faces hidden behind the threads belong to the Hazara people, who have been persecuted in Afghanistan since the end of the nineteenth century, but who are also not welcome in neighbouring Pakistan or Iran. Unfortunately for them, Hazara are easily recognized by their Asian features. The artist thus takes refuge in an old superstition, though she pushes its usefulness to the point of absurdity: being able to hide behind a mask when necessary may function in a work of art, but it fails miserably in reality.

Attaii’s embroidery is very finely done; it turns each of these small images into something precious. The artist first poked holes around each face by hand with a needle to limit the injury (to the photographs). She then wove a thread very closely and precisely through these holes nineteen to twenty times. The neatly cut pieces of wood on which the photographs are mounted give the images a physical, sculptural quality. The time required to make them contributes something very urgent and serious to the narrative.

Latifa Zafar Attaii, One Thousand Individuals, 2021/22, Passport photographies, 3 cm x 4 cm each, embroidery, wood, color; Commissioned by Verein Treibsand, Courtesy of the artist; photo: Chantal Romani

Embroidery, says the artist, is also something that’s done while waiting for the arrival of one’s beloved—an activity relating both to the dowry and to concern for his safe return. Thus this portrait series is ultimately also an ode to life, to possible happiness.

Latifa Zafar Attaii, One Thousand Individuals is in the exhibition The Other Kabul: Remains of the Garden (3 September – 4 December 2022) at Kunstmuseum, Thun.

Susann Wintsch is curator at Treibsand Contemporary Art in Western Asia and beyond, Treibsand (Zürich, Switzerland) exhibits original video works by artists and studio films on artists living in Western Asia and beyond.