Paint, paper, fabric, yarn, thread, resin, dye, glaze, and clay. These words could stand on their own as material objects: things or stuff. Or they might invite the presence of a subject, an individual, or a group, who then acts to bring these objects into productive relationships with each other. Craftivism. Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms is an exhibition which explores what happens when politics speaks in the language of craft.

There is an emerging trend in contemporary philosophy: a group of thinkers who are exploring “new materialism” or “object-oriented ontology”. These are people who are seeking to reimagine our relationships to objects, and to redefine what an object might actually be. In the new materialist tradition, the physical action we call “throwing on the wheel” is to be considered an object, a “thing” which is just as much of an object as the finished ceramic pot or vessel.

Discussion between artist and viewer, interaction between viewer and artwork, the transmutation of raw materials into craft are all “objects” that underpin this exhibition. The artists involved are concerned with what their objects, assemblages and installations can say; they show us how the materials and practices involved can be induced to speak. The intrinsic voice of the material and the point where it intersects with an artist’s technique is at the heart of this exhibition’s politics.

Feminist theorist and new materialist Karen Barad, whose philosophical writings are intertwined with her experience as a theoretical physicist, advances a theory in which “matter and meaning cannot be severed”. For Barad, an artwork, its component parts, its materials, technique and its political project, are all distinct objects existing in a state of quantum entanglement. She argues that “feeling, desiring and experiencing are not singular characteristics or capacities of human consciousness”; or in other words “matter feels, converses, suffers, desires, yearns and remembers.”

I believe this theory, in which objects have a kind of private life of their own, is an illuminating methodology for reading the exhibition Craftivism. When the constituent materials and techniques used in creating an artwork are recognised as possessing their own unique experiences, desires and emotions, we can start to grasp the embodiment of the exhibition’s byline: Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms.

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, Pewter dickhead 2, 2015, earthenware, glaze, gold and platinum lustre, 100 x 49.5 x 41 cm Recipient of the 2015 Sidney Myer Fund Australian Ceramic Award, Shepparton Art Museum Collection, © the artist

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran’s Pewter Dickhead 2 2015 gazes lustily at you from its cardboard pedestal as you reach the top of the stairs. The figure beckons wryly, a gleeful grin spreading across its face. I’m instinctively drawn to the Dickhead, pausing only briefly to parse the pastel ceramic scissors, braids, lattices and avocado slice of Tai Snaith’s A world of her own (Dramatic assemblage, Loose knit, Known history) 2018. Approaching Nithiyendran’s playfully lewd idol, a tumult of associations begin to flood my mind.

The creature’s oversized bobble-head rests loosely atop a thick black-glazed body, supported in turn by two trunk-like legs of roughly extruded clay. Its mask-like quality, somewhere between a marshmallow and a motorcycle helmet, recalls the Dai Tau Fut (Big Head Buddha) mask employed in Cantonese Lion Dance. Originating in Guangdong province, it features a dancer whose papier-mâché helmet-mask is in the guise of a Buddha with electric blue hair and a joyous, mischievous smile. This character’s role is to tease the lion, weaving and laughing through the crowd. I feel the Pewter Dickhead 2 fulfils a similar role, inviting and teasing the public, its imp-like tongue lolling lasciviously from between a wide lipstick-red smile. Even Nithiyendran’s colour palette echoes the Dai Tau Fut mask, with the ceramic dreads of the Dickhead glazed an equally striking ultramarine, and its mad rictus grin no less garishly red than the Cantonese Buddha-head’s lips.

The creature’s oversized bobble-head rests loosely atop a thick black-glazed body, supported in turn by two trunk-like legs of roughly extruded clay. Its mask-like quality, somewhere between a marshmallow and a motorcycle helmet, recalls the Dai Tau Fut (Big Head Buddha) mask employed in Cantonese Lion Dance. Originating in Guangdong province, it features a dancer whose papier-mâché helmet-mask is in the guise of a Buddha with electric blue hair and a joyous, mischievous smile. This character’s role is to tease the lion, weaving and laughing through the crowd. I feel the Pewter Dickhead 2 fulfils a similar role, inviting and teasing the public, its imp-like tongue lolling lasciviously from between a wide lipstick-red smile. Even Nithiyendran’s colour palette echoes the Dai Tau Fut mask, with the ceramic dreads of the Dickhead glazed an equally striking ultramarine, and its mad rictus grin no less garishly red than the Cantonese Buddha-head’s lips.

The Dickhead interrogates and pokes fun at the idea of a devotional object, playing irreverently with the concept of a religious idol. There are shades of the Hindu goddess Kali, some of whose attributes—jet-black skin, red pointing tongue, long necklace of skulls—are clearly present in Nithiyendran’s figure. The necklace of skulls, or Mundamala, is an object worn not only by Kali, but also the krodha-vighnantaka “fierce destroyers of obstacles” in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. As the Dickhead uses humour to attract and play with the viewer, the Mundamala appears as a dark and unexpected counterpoint. Each finely detailed skull has its eye-sockets and teeth etched carefully into rolled white clay balls, threaded thickly on a strand, depending from beneath the mask all the way down to the solid elephantine feet.

Goddess Kali dancing on Shiva.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Goddess Kali dancing on Shiva. 19th century

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

If there is something of the fierce feminine Kali in Nithiyendran’s Dickhead, there is also an allusion to the Ancient Egyptian household deity, Bes. The Dickhead‘s thick-set legs and nub-like phallus are distinctively reminiscent of many statuettes of the ancient, household-protector god. Where Kali represents fearsome female martial power, Bes was a smiling male guardian of children and women in childbirth. As he warded off evil, he also became associated with some of life’s basic pleasures: music, dance and sex. This Kali-Bes duality speaks to the statue’s original siting prior to the Craftivism exhibition, where it was presented as part of Archipelago, an installation of ceramic works in the 2015 Sidney Myer Fund Australian Ceramic Award. The other creatures in Archipelago possessed similarly complex gender identities; they were not willing to be reduced to a definitive male-female binary.

If there is something of the fierce feminine Kali in Nithiyendran’s Dickhead, there is also an allusion to the Ancient Egyptian household deity, Bes. The Dickhead‘s thick-set legs and nub-like phallus are distinctively reminiscent of many statuettes of the ancient, household-protector god. Where Kali represents fearsome female martial power, Bes was a smiling male guardian of children and women in childbirth. As he warded off evil, he also became associated with some of life’s basic pleasures: music, dance and sex. This Kali-Bes duality speaks to the statue’s original siting prior to the Craftivism exhibition, where it was presented as part of Archipelago, an installation of ceramic works in the 2015 Sidney Myer Fund Australian Ceramic Award. The other creatures in Archipelago possessed similarly complex gender identities; they were not willing to be reduced to a definitive male-female binary.

This work can be read as an accretion of references to religious statuary and celebratory dance ritual, but it makes these references in a language of cheeky performance. The white-washed cardboard pedestal, with its black spray-painted, downwards-pointing arrow, is an invitation to invert devotion, to turn religious iconography on its head. At the exhibition’s install, I imagine the Dickhead alive, leaping from its “this-way-up” cardboard packing, flipping the box on its opening to create its pedestal, and siting itself on top. The Dickhead stands there still, revelling in its lack of manners, wringing its hands with glee as it anticipates the affront or delight it may bring its visitors.

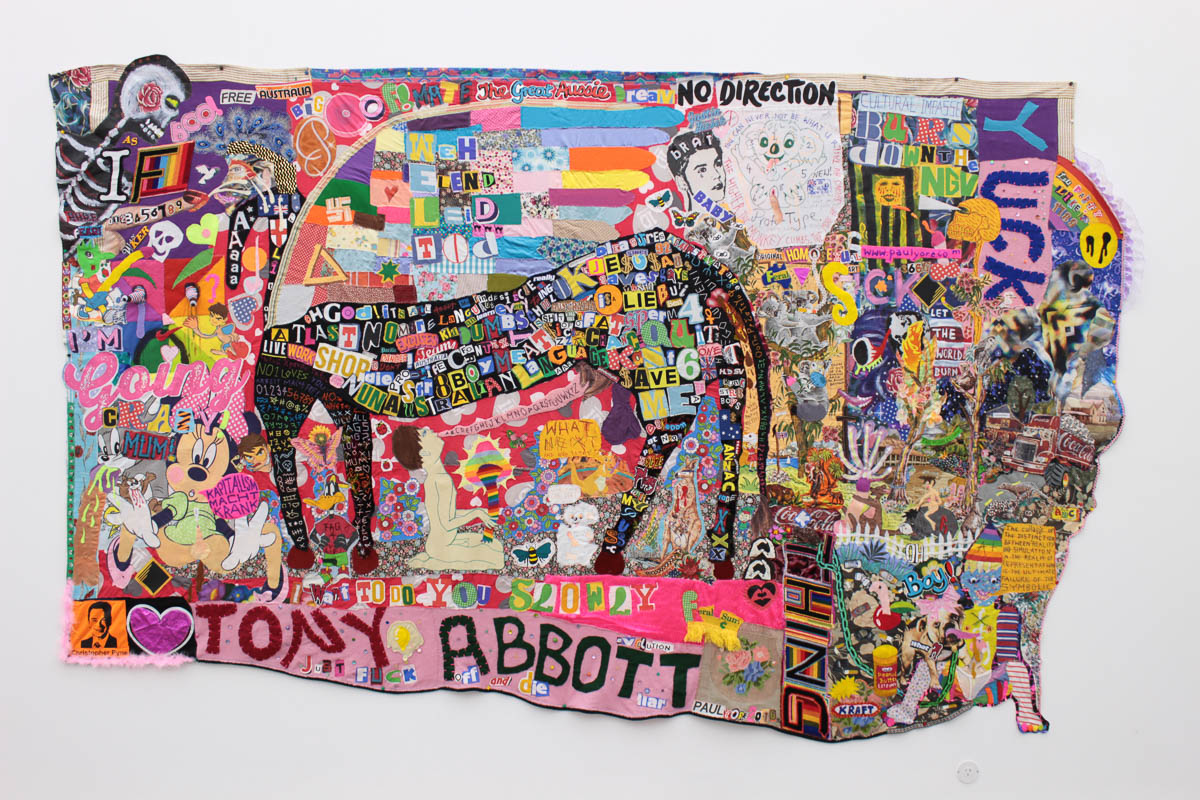

Paul Yore

What a Horrid Fucking Mess, 2016

textile wall hanging; mixed media

210 x 342 cm (irreg.)

purchased with Ararat Rural City Council

acquisition allocation, 2016. Collection of Ararat

Gallery TAMA. © the artist

Hanging behind and to the left of Pewter Dickhead 2 are two vivid quilted tapestries by Paul Yore. Art is Language (2017) presents a square field with various teen heart-throbs, appliquéd thickly onto a background of Day-Glo technicolour camouflage. An irate tweety-bird and a sad-looking cat are crowded in by Harry Styles, Justin Bieber and a Romeo and Juliet-era Leo DiCaprio. The whole assemblage is then speckled with inverted skulls, recalling the Mundamala adorning Nithiyendran’s Dickhead. A “qwertyuiop” keyboard, stylised in a stitched pink-on-black grid, suggests the process of speaking through fabric. Cut-up letters spell out “ABJECT – fuck language”, with all the random wonkiness of a magazine-mined ransom note.

Allowing the diverse pieces of fabric to speak, both to each other and then outwards to the viewer, is a central activity of Yore’s work. This multiplicity of carefully chosen cartoon/celebrity/kitsch objects are removed from their original contexts and hand-stitched into dazzling landscapes of sex, politics, economics, gay identity and Australian cultural critique. In What a Horrid Fucking Mess (2016), this fabric glossolalia reaches fever pitch. The deeper you stare into the 2 x 3.5m tapestry, the faster your eyes start to move over each joyously lewd creature and phrase: Minnie mouse ejaculates daintily as the words “KAPITALISM MACHT KRANK” emerge in a pink speech bubble. Beneath a black bull-like animal, covered in more ransom-note style cut-ups, kneels a naked boy. He’s fellating the bull-thing, whose long pink member is stitched with the twenty-six letters of the Latin script. The boy also holds aloft a shining, rainbow-coloured magic mushroom, which speaks of both countercultural revolt and the birth of human language. Psilocybin, the psychoactive chemical within “magic mushrooms”, was theorised by ethnobotanist Terence McKenna as leading to the first uses of language in early humans. Whilst Yore’s references are often drawn directly from counter-culture, he creates his own garish Australian mirror-world. By implicating a Christopher Pyne tea-towel in a theoretical homosexual relationship with Tony Abbott, or defiling the Herald Sun logo into “Feral Scum’, Yore lets the fabric find its own anarchic, unrestrained voice.

Deborah Kelly

LYING WOMEN (still) 2016

digital video, 16:9 ratio, colour, stereo, 3:56 minutes

Cinematography by Christian J Heinrich

Editor: Elliott Magen

Original score composed by Evelyn Ida Morris

Soundscape: Adam Hulbert

© the artist, courtesy the artist

Behind blackout curtains in the next space is Deborah Kelly’s video work LYING WOMEN 2016. Again, objects are brought from their initial contexts, given new voice and meaning as they are cut out and multiplied, freed from their frames. Here, the objects in question are reclining nudes from the Western art historical canon, with Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) featuring prominently. Removed from the pages of art history texts or perhaps post-cards, the women are at various scales, arrayed on top of each other in chaotic piles atop black felt. These piles then resolve into ordered patterns, before scattering, to frenetically circle each other in vigorous stop-motion animation, women’s hands occasionally entering the frame to rearrange the nudes. A soundscape of alternately laboured and gentle female breathing gives further life to the liberated figures. When we see the hands of a maker manipulating the images, before receding, there is an immediate sense of the artist as liberator. Kelly’s women, having been freed, eagerly pursue a dance all of their own.

Yore, Nithiyendran and Kelly all involve their public in dialogues which emerge gradually. In Yore’s case, this occurs as layers build up in the reading, and a mounting hypnotic accretion of meaning plays out against a field of swimming colours and letters. Nithiyendran’s puck-like creature addresses its audience via sly and playful teasing, while Kelly’s video work gives the sense of being granted private access to the unknowable rites of a rapturous coven.

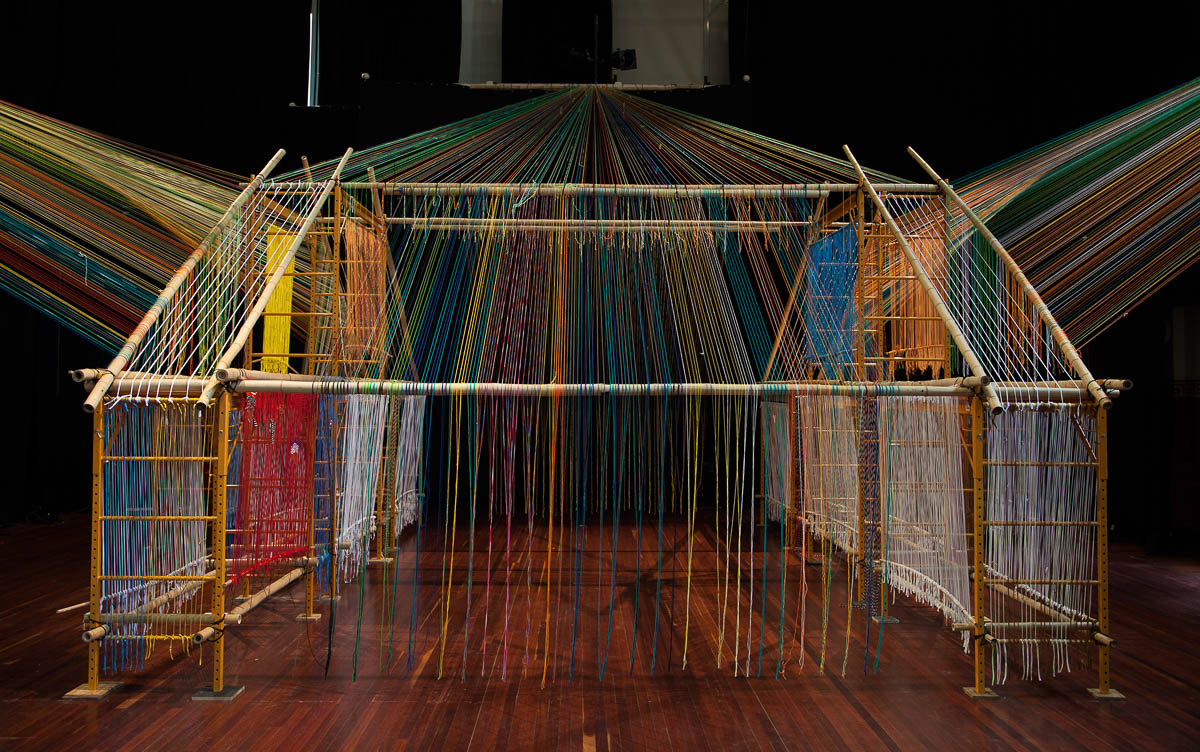

Slow Art Collective

Archiloom, 2016 [detail]

installation view at Arts House, Melbourne

yarn, rope, bamboo, recycled fabric, cable ties,

scaffolding, dimensions variable

image: Eugene Howards

Courtesy and © the artist

Two other artists in the show involve the public in their worlds through even more direct and immediate methods. Slow Art Collective’s Archiloom 2018 gently and warmly occupies the bulk of a single white-walled space. This bamboo and coloured yarn structure has the visual language of an unfinished suburban house, mated with the quietly utopian craft ideals of street-based yarnbombing. The soft yellow bamboo is however much more calming than any builder’s treated pine, and the multi-coloured yarn is still bright and vivid, retaining the pigment that often gets washed from outdoor guerrilla yarn-interventions. The crucial aspect here is the Collective’s democratic invitation to partake in its construction, with signage exhorting visitors to take fabric and ribbon offcuts from a pouch and to then introduce these into the work. To a soundtrack of softly undulating ambient electronica, produced live in the space by a collective member, I saw visitors of all ages deeply absorbed in their contributions, weaving their threads in considered concentration.

Hiromi Tango Hiromi Tango, Amygdala (Fireworks) 2016, neon and mixed media, 120 x 140 x 40 cm, Courtesy the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney / Singapore

Hiromi Tango’s Amygdala (Fireworks) 2016 is a riotous halo of coral-like red and orange threads, hacky-sack balls, pipe-cleaners, felt flowers and clovers, surrounding a neon-framed mirror. The mirror sits at the centre of this vortex, a polished scrying pool at the centre of irregular, crocheted and twisted forms arrayed in their three-dimensional profusion. The twisted, often blood-red shapes feel organic, microscopic, evoking the interior mechanisms of a cell, or the movement of bacteria and flora within the gut. The curvilinear orange neon bar defines the boundary between mirror and fabric. It is synaptic, pulsing its light as thought, an electrical impulse or emotion, calling the viewer into the crowded interior of the work. Standing there, with your head peering into the blood-warm void, you are confronted with your own reflection, illuminated weirdly by the orange neon.

The work’s title refers to an area of the brain in the temporal lobe: the amygdala, which performs a primary role in decision-making, memory and the processing of emotions (particularly anxiety, fear and aggression). The fight or flight instinct is thus thought to originate in the amygdala. Facing your own reflection, ensconced in light and these contorted, yet beautiful forms, there is a sense of accelerated meditation. You could be put to flight by this pull, or you could let the sensation grow, as the objects crowd around you and your introspection deepens. Many might recoil, or withdraw after a moment, but if you allow Tango’s objects to speak, and your own image to float within their radiance, you will find yourself basking in the warmth of Tango’s healing environment.

Leaving the Shepparton Art Museum (SAM), walking down past the council buildings and the towering soldiers of the war memorial, the figures and forms of the exhibition percolated through my mind. Yore and Nithiyendran’s figures danced before me, and I imagined them superimposed on the monolithic marble and bronze of the Diggers at the memorial. The possibilities that arose for me, having come into contact with these irreverent and playful works, were highly productive: I saw new networks of objects, interlinked, partaking in alternately critical and constructive dialogues. An old Australia confronted with visions of its new modernity. As the softened urban forms of the Slow Art Collective’s Archiloom settled like a spectral balm over suburban Shepparton, I felt certain that the craftivists were engaged in a much-needed re-envisioning of art’s potential. Whether it is in the re-interpretation of religious icons, or the stimulation of neurological processes through healing craft techniques, the craftivists are working to engage us in contemporary concerns. They are showing us how objects can speak.

Craftivism. Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms is at Shepparton Art Museum until 17 February 2019. Artists include: Catherine Bell, Karen Black, Penny Byrne, Erub Arts, Debris Facility, Starlie Geikie, MichelleHamer, Kate Just, Deborah Kelly, Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, Raquel Ormella, Kate Rohde, Slow ArtCollective, Tai Snaith, Hiromi Tango, James Tylor, Jemima Wyman and Paul Yore. Curators: Anna Briers and Rebecca Coates.

Craftivism. Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms is a Shepparton Art Museum curated exhibition, touring nationally by NETS Victoria:

Shepparton Art Museum (VIC) 24 November 2018 to 17 February 2019

Warrnambool Art Gallery (VIC) 4 March to 5 May 2019

Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery (VIC) 17 May to 21 July 2019

Museum of Australian Democracy (ACT) 6 September 2019 to 2 February 2020

Bega Valley Regional Gallery (NSW) 18 April to 13 June 2020

Warwick Art Gallery (QLD) 3 July to 15 August 2020

University of the Sunshine Coast Art Gallery (QLD) 12 September to 31 October 2020

Author

Oliver Raymond lives in Melbourne, where he wanders the streets in search of weird tableaux and uncanny urbanity. He is starting to turn his attention to putting into words his impressions of art, architecture and the world.

Oliver Raymond lives in Melbourne, where he wanders the streets in search of weird tableaux and uncanny urbanity. He is starting to turn his attention to putting into words his impressions of art, architecture and the world.