Jenuarrie is a Queensland artist who draws on the Lapita ceramic tradition of her region to produce striking unique works. Here is an extract from a recent book Gift of Knowledge, where Jenuarrie tells the story of how she came to produce this work, and the cultural values that guide her life.

To put my work in context, to retain its rightful meaning and connection to my mother’s paternal bloodline, give them all the respect they deserve, and to honour the land where I was born, I need to go back through history and speak of the longer connection I have with my Australian Aboriginal heritage.

On reflection as a Koinjmal Aboriginal woman who did not begin her career as an international artist until after turning 40, I realise I have been blessed in my mid-life “sea change” with a diverse, rich cultural background that has influenced my creative work. My knowledge and connections within my cultural heritage as I worked across diverse genres of art, has offered a very exciting aspect to my career that acknowledges my ancestors for the privilege to share my late-in-life experiences.

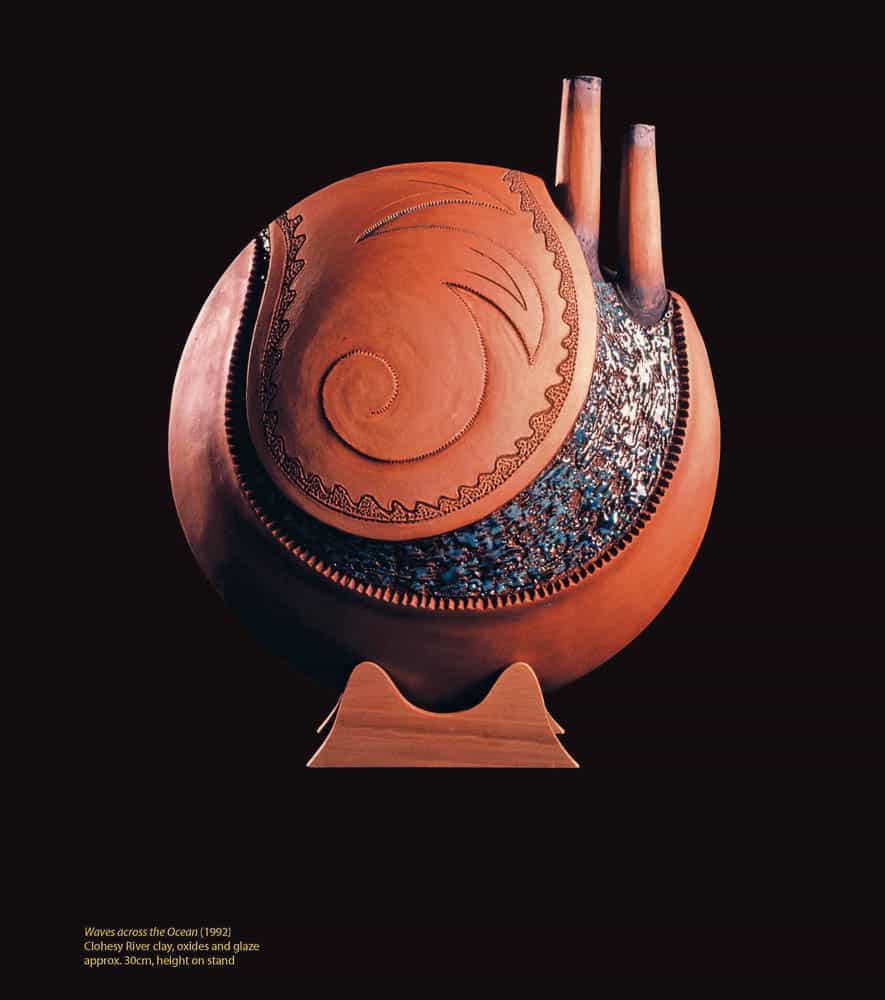

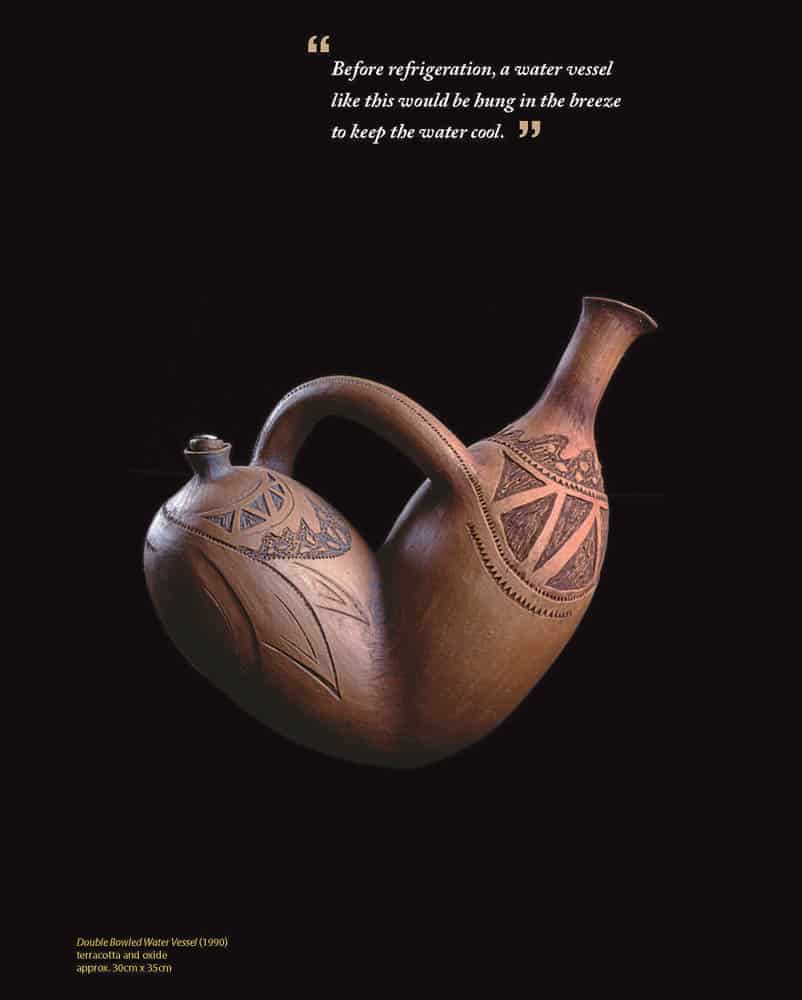

My heritage also embraces Vanuatu (formerly New Hebrides) and New Caledonia, and the hand-built clay traditions and fascinating designs of the Lapita pottery. These link to the cultural origins of the potters who produce the work. My particular interest has always been in their traditional practice, their work environments, the different clay compositions used from the local regions and the way the work was fired.

As a practising artist potter who is not an academic or theorist, I will touch briefly on the origins and chronological history of the Lapita culture according to what I learned from my research.

What intrigues me are the various theories among the writings, and why the number of publications available on this important history of Melanesia is so scarce.

My original interest in pottery goes back a long way. I dreamed of one day owning a lovely pottery dinner set. Knowing my dream was not affordable, I realised that I would have to make it myself. My sisters and I were raised knowing if we wanted or needed a new dress or winter jacket, we had to either help our mother to make it, or make it ourselves. Knowing how my family, throughout their adult lives, had acquired some amazing skills in life, I did not see the possibility of making my own dinner set daunting.

My concern was more about how long this journey of learning would take. I questioned myself about taking the time to first learn the skills so that I could eventually make it. With no cultural connections to dinner sets on highly polished dining room tables, I found myself drawn over time to a more purposeful connection and relationship than just making a dinner set. I became enthusiastic and excited about finding a more meaningful pathway that took me to researching “my other story”, and much later, discovering how it intertwined with my Aboriginal songlines.

I reflected on the scene of my past employment as a domestic at a local refectory for twenty-six nuns. My duties involved near perfection in the setting up and serving of meals. With everything precisely in its rightful place, it struck me as a very lonely and sterile environment. When the dinner bell rang, the nuns filed into the room, with no speaking allowed. While Mother Superior performed the blessing, I never observed any expression of interest in the beautiful crockery and highly polished cutlery set out upon the table.

I contrast this with the dining habits of my own childhood home, with all my brothers and sisters. When we were called to the table, we would jostle ourselves around the very confined space. There was always a fresh tablecloth. The boys would be reminded of the rule of always wearing shirts to the table. We were all reminded, no elbows on the table, and no singing. That was deflating, especially when we had just been listening to all our favourite hit tunes on the radio. The crockery was usually unmatched, with a few much loved special pieces. When new cups were purchased, they were revered with lots of admiration and talk about what we loved about them. If it was your turn to set the table, you were in luck and gave a new cup to yourself. What a trade off!

My belated interest in Melanesia and the Lapita pottery tradition began as inquisitiveness, not from any heartfelt yearning of a lost cultural connection to an unknown part of my heritage. My ability to create my own pottery became a driving force and ignited my interest in learning the history of the Lapita “trail” and the origins of the hand-building practice. I was in awe of the Lapita pottery tradition in its necessity for daily use and trading, as it required strenuous labour by the traditional potters to find and use the clay with unconventional tools from which they were able to produce objects of such beauty and magnitude.

Often Lapita designs are made with a limited number of tools for impressions and carvings to make a singular pattern around the circumference of the art piece, which can include other designs to form an overall intricate pattern. This form of design is now termed Lapita pottery and can be identified in origin by the distinctive designs and appearance.

I found I had a natural ability for hand-building using what nature provides to the exclusion of any other genres of pottery making. However, my work doesn’t strictly follow the Lapita tradition. I made a conscious decision not to stay true to the Lapita design iconography where the designs are replicated, abstract, controlled and dissected to read “story” connected to culture, or “story” connected to daily life.

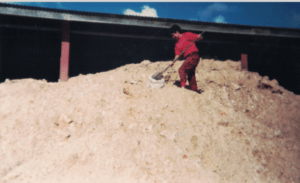

Through testing and experience, I found suitable clay for specific pieces of artwork. In this way, I began to learn and appreciate the material, the art form and the process. Repetitive sections will invariably find a similarity to my “story” design references and meaningful interpretation.

I have often been asked to describe my work and the many cultural connections that intertwine the expression of my art pieces. I find this difficult to explain, as Lapita pottery was referred to as a “lost” art form. However, for me it was never “lost”, because I never knew it existed in the first place until later life. Outsider observers have described and published information on Lapita pottery, but sadly no information was passed through generations of my ancestral bloodline to me as usable, precious or valuable knowledge.

But discovering my cultural connections was exciting. Starting this journey was not about initiating a career path for myself, or even creating an arts business to pay the mortgage or have what is popularly termed “a real job”. It was all about a sense of belonging, a central place where I could take ownership of my identity and purpose in life. I can liken this research to opening my Pandora’s Box. It was the beginning of finding my peace and mending my “songlines”.

As a beginner I found very few publications focusing on instructional skills or creativity. I wanted to know what was possible and what technical challenges I might face as I developed my practice. My practice in creating items for daily use extends to creative formations that are both technically challenging, yet still retain their functionality.

But ignorance was bliss. It forced me to use my own imagination and gave me the freedom to experiment without rules and constraints. As a result, I stopped wasting any more valuable time on research, concentrating instead on perfecting my hand-building skills.

But I didn’t do this in isolation. I owe much of my successful career to an exceptional man who has since passed on. I responded to an advertisement in the local paper promoting pottery workshops, and eagerly enrolled. The teacher was an Australian master craftsman and potter whose wife was a skilled weaver and crafts-maker from Papua New Guinea. Their collective knowledge was extensive, appropriate and meaningful to me as a learner, with the combination of cultures and the influence of Lapita practice filtering through in their techniques.

At first, I worried about losing my Aboriginality through the new work I produced. In hindsight, I need not have worried. It soon became apparent that I needed to find my own way by getting lost in my own creativity and my own signature work. As a balanced identity developed, it gave me the confidence to power on.

I joined the small class of local individuals that included a number of different cultural identities. Our teacher was a hard taskmaster who would accept no less from us than perfection. “Learn and practice sound constructional skills so that they become your habits”, he would say. “Don”t keep repeating mistakes as they will become the habits your memory will remember”. Wise words indeed!

I believe that my “belonging” to this group of interesting people, who were all very studious and serious about gaining good constructional skills, put a lot of peer pressure on me to succeed. Saturday became my favourite day, when homework was revealed, and the personalities of my companion potters were expressed in the creations they presented.

Some were wildly creative. I wondered what had influenced them to be so spontaneous. While I can smile about “reveal day” now, it offered some great examples of how our articulate teacher could demonstrate how to overcome difficult challenges.

Although we were all taught the same techniques, it was evident to the trained eye that shapes, markings and approaches to using design clearly distinguished our individual cultural identities. At this time my artistic desire was to use my creativity to signify my skills in the making of original pottery pieces, master technical challenges and clearly identify my signature work.

Choosing to embark on a new career as a contemporary visual artist was very challenging for all artists living in the FNQ region. Being so far from Brisbane, support for cultural development was lacking until the introduction of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Visual Arts Course at the Cairns, Barrier Institute of TAFE.

My work eventually found its own uniqueness, but with distinctive links and references to all my cultural connections. It just is. My artwork images and marks, reference and pay tribute in a generic way to the ancestors of the land that grew me up.

Spiritual connections and the recall of passing time are evident, repeatedly surfacing in my work as a subconscious calling.

What is most meaningful to me is the comfortable integration of culture, thought and design.

I am yet to make the pottery dinner set of my dreams that set me on this journey, but I am consoled—who needs one when there are plenty of odd cups, saucers and dinner plates in the kitchen, and plenty of smiling faces around the table.

Learning good foundational skills from your earliest beginnings is a guide that enables you to create the “magnificent”. They are skills that have the capacity to fulfil your dreams of becoming a great potter or whoever else you may want to be.

You can purchase Jenuarrie’s book Gift of Knowledge for $50 here.