Lace depicting the Logan and Albert Rivers installed on the façade of Logan Art Gallery during June and July 2020. Photograph taken by the author.

Pamela See reviews the Lace exhibition by Mary Elizabeth Baron at Logan Art Gallery, which marks the subsiding of the first COVID-19 wave in Queensland.

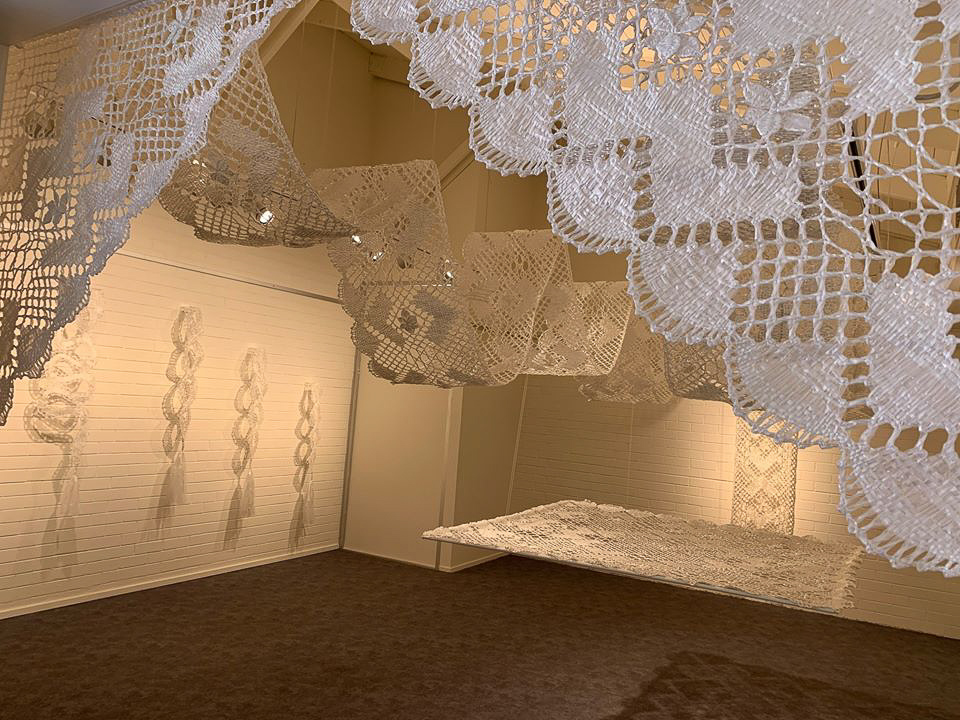

During mid-June 2020, the Logan Art Gallery re-opened to the public with a solo exhibition by local textile artist Mary Elizabeth Baron titled Lace. Her large installations were primarily woven using re-purposed household plastic. They were positioned to lead visitors into one of the galleries, with artworks both attached to an external façade and inside the main entrance.

Although the etymology of the term ‘lace’ is unclear, its variations across the romantic languages are illustrative. “Laccio” in Italian and “Lazo” in Spanish both imply “to snare”. The term “laz” appeared in French during the thirteenth century, defined as “cord made of braided or interwoven strands”. However, the tradition was described in the same language as “passement” during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This was in reference to its role in adorning the edges of garments.

Fanny Bury Palliser made reference to the following passage in Isaiah XIX, in The History of Lace published in 1875, “They work in fine flax and they weave networks”. It was used to interpret the figures of weaving figures depicted in Egyptian tombs. In 2007, the Chief Curator of the Museum of Art and Design conversely described lace as “creating interlocking structures in patterns that permit light to pass through them”.

The diffusion is also a metaphor for exclusivity. In Western Europe, between its fourteenth-century emergence and the sixteenth-century dissolution of monasteries, lace was reserved for ecclesiastic purposes. In the intervening two centuries prior to the invention of machined lace, it would adorn royalty. Louis XIV issued ordinances specifically restricting its wear amongst subjects whilst conversely “subsidising” royal lace manufacturers.

In A Dictionary of Lace published in 1999, Pat Earnshaw wrote:

Louis XIV’s statesman Mazarin, as one of the last acts of his life, brought out an edict ‘Contre le Luve’, i.e. against all luxurious dressing. The acute concern he aroused amongst the socialites stimulated their elegant lampoon La Revolte des Passemens. The charming engravings of Abraham Bosse (1602-76) throw a revealing light on their obsession with finery – the noble ladies and gentlemen discard their lace as if their own flesh was being torn away.

A detail of a painting by Hyacinthe Rigaud of Louis XIV. During his reign, the king issued ordinances restricting the wearing of lace in France whilst supplementing its production for royalty. Image source: Chateau de Versailles, “Versailles and the Royal Court”, accessed 31 July, 2020

Although no longer socio-economically divisive, lace continues to demarcate the private and the public. The application of elaborate “iron lace” on building facades became an architectural standard during the nineteenth century. Passements, in garments, remain positioned around entry points, such as hems, colours and sleeves.

Textile artist Mary Barron and her mother at her exhibition Lace in June 2020. Image source: “Mary Barron”, Facebook, 15 July, 2020, accessed 31 July, 2020,

When I met Barron at Logan Art Gallery she was wearing a Tudor inspired shirt. Its generous sleeves and square neckline were adorned by her own handwoven lace. In new company, she often introduces herself with the explanation that she “came to art… after raising [a] family”. To facilitate this, she undertook art classes with the Brisbane Distance School of Education when her youngest child “near[ed] the end of her schooling.” However, her preoccupation with lace both preceded and proceeded motherhood.

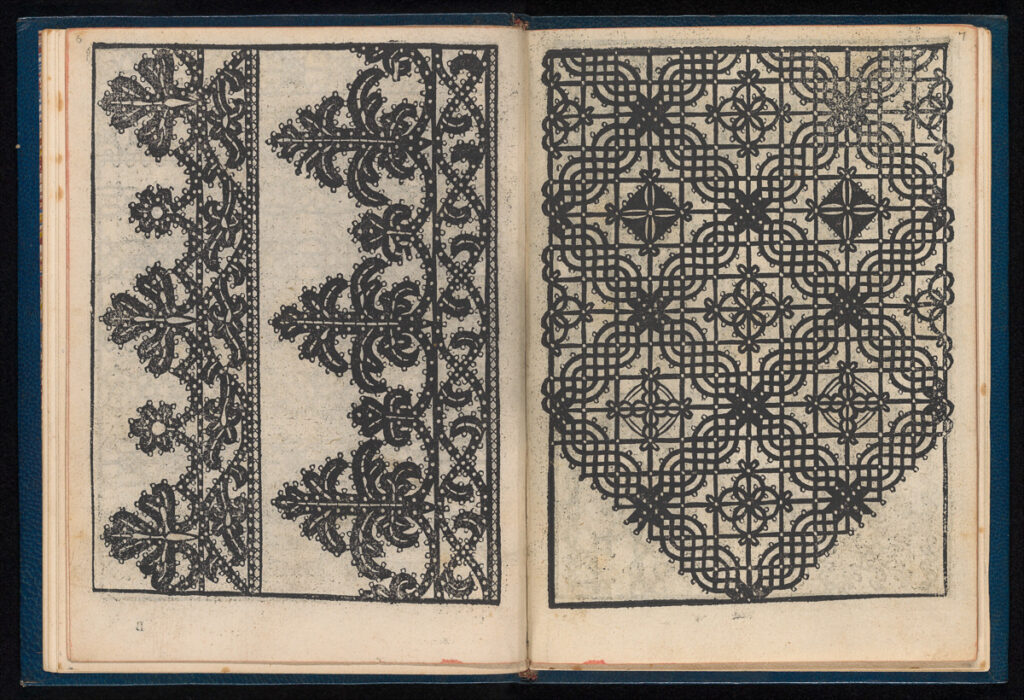

Born and raised in Brisbane, Barron developed an interest in the craft as a teenager after reading about a lace maker in a novel. During the 1990s, she attended classes in bobbin lacemaking at a hall. They rang on Saturdays over the course of a month. Although the precise origins of this technique are contested, peasants in Belgium began making lace using pillows and bones during the sixteenth century. Unlike its predecessor, cutwork, bobbin lace entails the “twisting and crossing” thread over a “pricked out” pattern. Bobbin lace was the subject of the first pattern book, Le Pompe: Opera Nova, published in Venice in 1557.

The proliferation of distinct regional variations of the tradition can also be attributed to an itinerancy imposed upon lace makers by changes in sumptuary law across countries such as Italy, France and England. In 1900, Neville Jackson wrote in The History of Handmade Lace, “…patterns and peculiarities became identified with certain localities”. The examples she provided included Pelestrina lace, Buckinghamshire lace and Mechlin lace.

The Metropolitan Museum, “ Le Pompe: Opera Nova”, accessed 31 July, 2020.

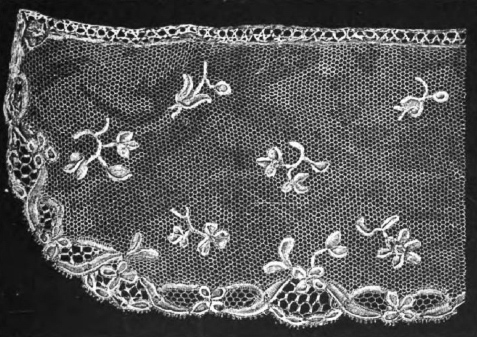

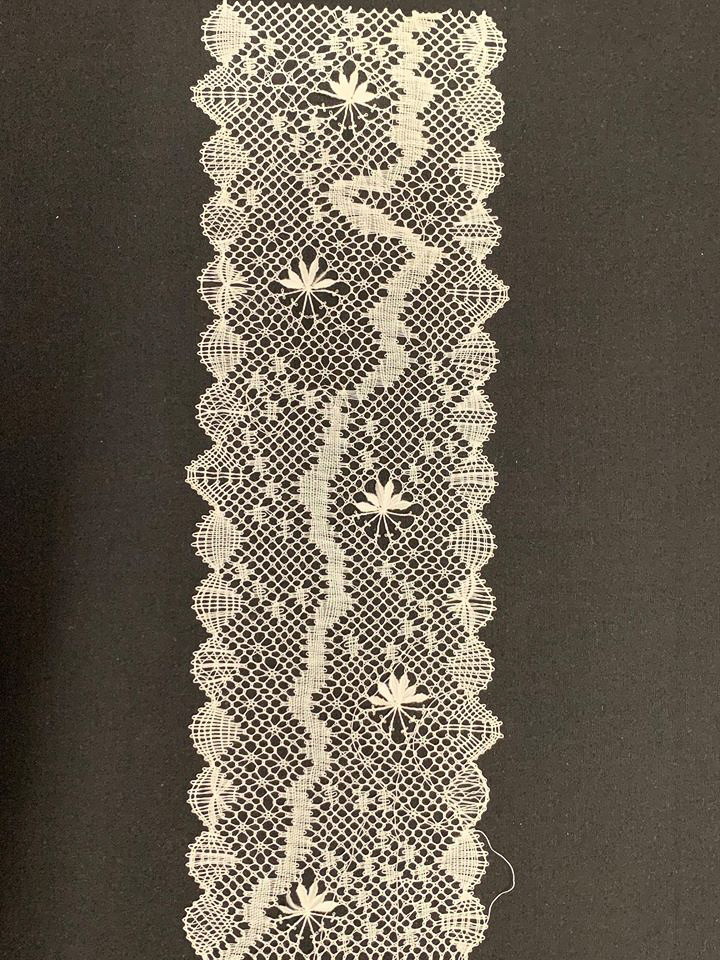

Whereas Barron has reproduced the Venetian patterns in Le Pompe: Opera Nova, the lacework in her exhibition Lace are site responsive. Two of the most prominent installations illustrate the Logan and Albert Rivers, which were discovered by Captain Patrick Logan in August 1826 and May 1827 respectively. The towns to be established on their banks during the nineteenth century included Yatala, Beenleigh and Loganholme. They supported the cultivation of cedar, cotton and sugar. The depictions of the river sections were pricked out from maps. She embellished the patterns with motifs representing the endemic Banksia Integrifora and Gossia Gonoclada. The latter, commonly referred to as the angle-stemmed myrtle, is an endangered species of flora. Her approach mirrors the regionally-specific traditions of lace in Europe. The integration of periwinkle motifs into Mechlin lace during the seventeenth century is a primary example.

- The studies for the large external lace installations depicting the Logan and Albert Rivers and endemic flora were woven using fine cotton. Image source: “Mary Barron”, Facebook, 5 June, 2020, accessed 31 July, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2555678408025394&set=pcb.2555679644691937&type=3&theater.

- The studies for the large external lace installations depicting the Logan and Albert Rivers and endemic flora were woven using fine cotton. Image source: “Mary Barron”, Facebook, 5 June, 2020, accessed 31 July, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2555678408025394&set=pcb.2555679644691937&type=3&theater.

- Mechlin Lace was known as “The Queen of Laces” and integrated depictions for flora. In this instance, the motif bears resemblance to periwinkle which is endemic to the region. Image source: Emily Jackson, A History of Hand-Made Lace (London: Scribner’s Sons, 1900), 123.

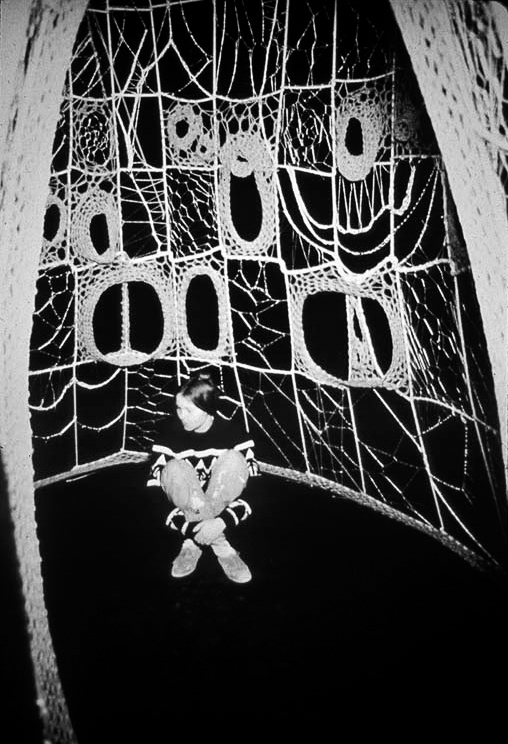

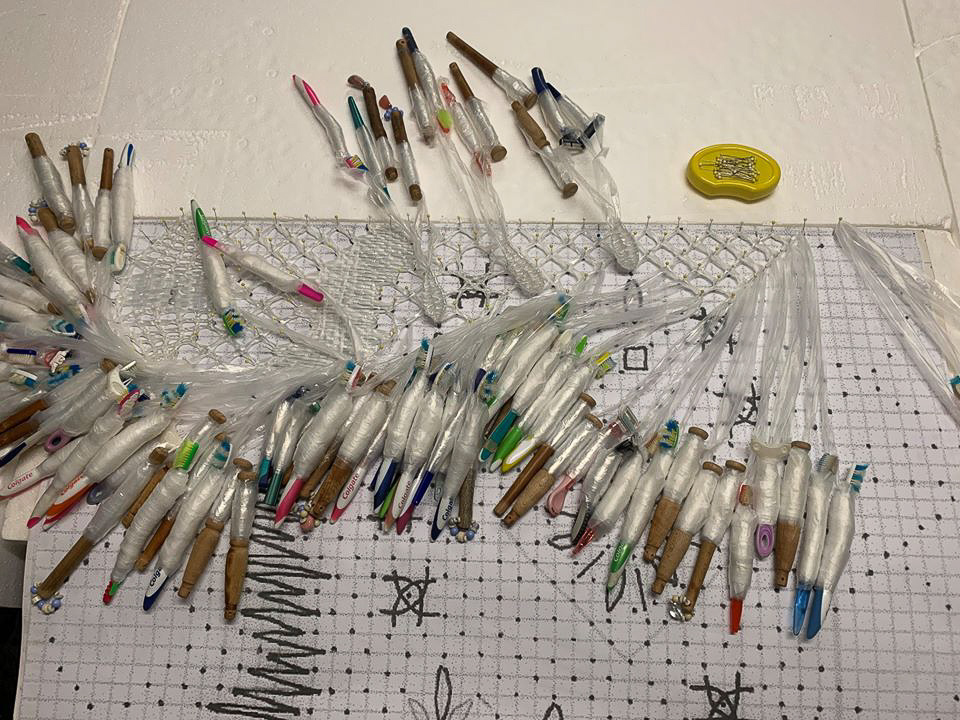

Barron departs with Europe tradition through her employment of repurposed plastic and cathedral-esk proportions. Through their materiality, the artworks are categorically craftivist. By the definition of Betsy Greer, the founder of the movement, the installations “foment dialogue”. Barron expressed her concern of the continued accumulation of household plastic despite the banned distribution of single use shopping bags in saying “You still have your bread bags, your plastic wrappings…” Her painstaking harvesting of this domestic resource involved collecting, cleaning and cutting. After winding the plastic onto bobbins, she pricked out and wove the 3.32m and 2.8m compositions in sections. The largest installation, suspended in the entrance to Logan Art Gallery, was 11m and depiction a portion of the Mary River in the Wide Bay Burnett Region of Queensland.

Lace being woven using repurposed plastic over a pricked-out pattern of the Logan River. Image source: “Mary Barron”, Facebook, 23 May, 2020, accessed 31 July, 2020

Lace installed from floor to ceiling at Logan Art gallery. Image source: “Mary Barron”, Facebook, 19 June, 2020, accessed 31 July, 2020

Whilst extrinsically investigating environmental degradation and place, it is the transgressions between the domestic and/or private space into the public that may resonate with many visitors. Second wave feminist artist, Faith Wilding, created a “Crocheted Environment” in 1972 titled Womb Room. Enveloping the space, the web-like textile confronted visitors with “contradictory sensations of security [and] entrapment, serenity and danger”. It was exhibited in a dilapidated mansion as part of a Feminist Art Program run by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro through the California Institute of Arts. The artworks were intended to “exaggerate, in order to exorcise, legacies of domestic women’s work.” The installations in Lace are similarly engaging.

The zeitgeist with the subsiding of the first wave of COVID-19 was reflected by the reopening of the Logan Art Gallery with this solo exhibition by Barron. She captured the aspirations for a more environmentally sustainable future through her monumental laces repurposed from plastic. Their agency stems from a combination of a high level of technical proficiency exercised in their construction and a comprehensive understanding of the complex connotations affiliated with the craft.

Symbolic of exclusivity and transition, lace serves to both conflate and, conversely, demarcate as an oft fine and permeable barrier. The continuing application of lace in bridal apparel, as veils and garters, is a contemporary example. Its sanctitude is historically evidenced by its restriction to ecclesiastic purposes during the early Renaissance in Western Europe. It represents a dialogue between the material and the immaterial, the public and the private, and the aristocracy and the proletariat.

Although Barron executes the craft with the intention of environmental activism, it is her own transformation which the lace represents that is of greater significance. The body of artwork is inherently auto-ethnographic of shifting her making from hobbyist to artist of influence in the region of South-East Queensland.

Further reading

Bryan-Wilson, Julia. Fray : Art + Textile Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2017.

Chateau de Versailles. “Versailles and the Royal Court”. Accessed 31 July, 2020.

Cranfield, Louis. “Logan, Patrick (1791–1830)”. Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Published first in hardcopy in 1967. Accessed 31 July, 2020.

Earnshaw, Pat. A Dictionary of Lace. New York: Dover Publications, 1999.

Goldenberg, Samuel. Lace, Its Origin and History. Massachusetts: Harvard University, 1904.

Greer, Betsy, ed. Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2014.

Hanlon, W.E. “The Early Settlement of the Logan and Albert Districts.” A paper presented to the Historical Society of Queensland, 27 March, 1934. Accessed 31 July, 2020.

Jackson, Emily. A History of Hand-Made Lace. London: Scribner’s Sons, 1900.

Logan City Council. “An Early History of Logan”. Accessed 31 July, 2020.

“Mary Barron”. Facebook. 23 May, 2020. Accessed 31 July, 2020.

“Mary Barron”. Facebook. 19 June, 2020. Accessed 31 July, 2020

“Mary Barron”. Facebook. 19 June, 2020. Accessed 31 July, 2020

“Mary Barron”. Facebook. 15 July, 2020. Accessed 31 July, 2020

McFadden, David Revere, Jennifer Scanlan, Jennifer Steifle Edwards and Museum of Arts & Design. Radical Lace & Subversive Knitting. New York: Museum of Arts & Design, 2008.

Pacific Standard Time. “Explore the Era”. The Getty Museum. Accessed 1 August, 2020.

Palliser, Bury. A History of Lace. London: Sampson Low, Son and Marston, 1869.

The Metropolitan Museum. “Le Pompe: Opera Nova”. Accessed 31 July, 2020.

Wohl, Kit and Chris Rose. New Orleans Icons: Iron Lace. Los Angeles: Pelican Publishing Company, 2018.

Institute of Contemporary Art Boston. “Crocheted Environment”. Accessed 1 August, 2020