How does keeping alive Joseon dynasty heritage help South Korea become a world leader in contemporary crafts?

It was a glorious spring day in South Korea. The air was alive with a dizzying variety of insects. Dragonflies, bees and butterflies were taking advantage of the mild sunshine and the blooming azaleas.

I was in Cheongju, a medium-sized city in the centre of South Korea, nestled in rolling green hills. Cheongju has a unique role in the world. While its economy is mostly based on high technology, the city takes great pride in its cultural heritage. Jikji, the first book in moveable metal type, was printed here in 1377. Cheongju has built on this history a focus on contemporary craft to become home to the largest craft biennale in the world today.

This corner of the world has quite a global presence. In the green hills around Cheongju is the village of Eumseong, where Ban Ki-moon was born, the revered Secretary-General of the United Nations. Despite being far from Paris and New York, South Korea plays a positive role on the world stage.

I was in a touring party visiting Cheongju’s local craft workshops. We stopped at the Baecheop (Traditional Mounting) Studio, where master HONG Jong-jin kindly invited us to swap our shoes for rubber sandals.

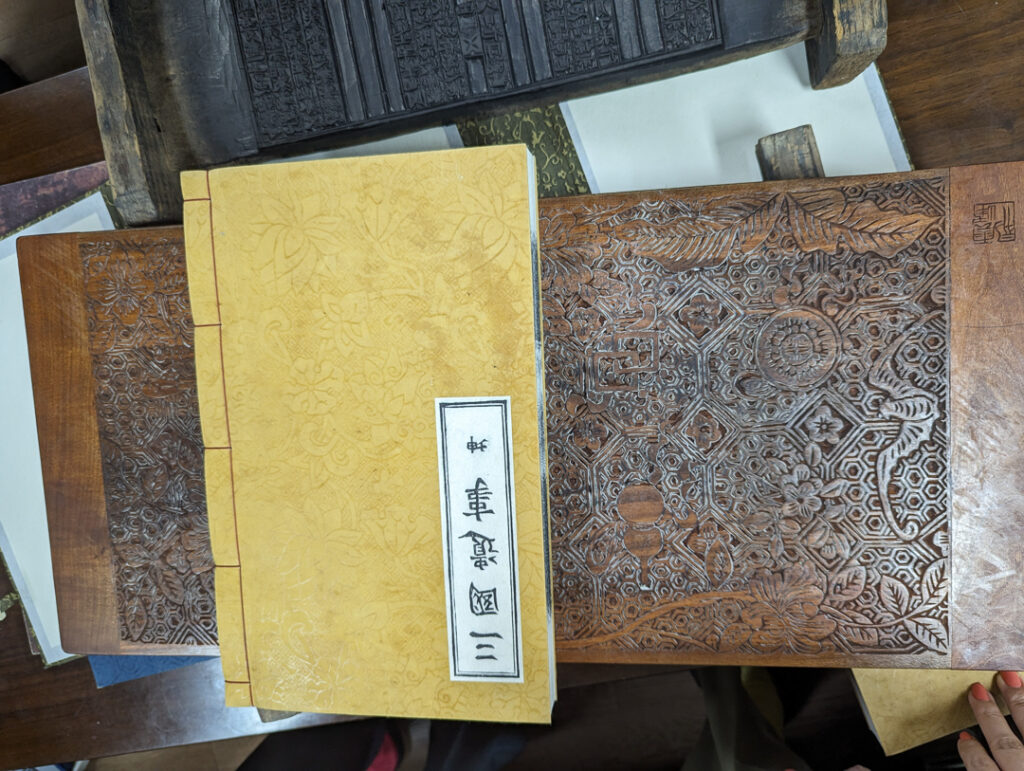

Master Hong proudly showed us some of the exquisite heritage publications he had recently reproduced, using locally handmade paper, textiles, woodblocks, brushes and inks. When he mentioned the process of natural dyes, we expressed interest in seeing his workspace.

Upstairs, we had to take off our sandals and walk just in our socks. What greeted us was a room the size of a basketball court whose floors, walls and ceilings had been painted with lacquer. It’s hard to describe what it’s like to be enveloped like this. Lacquer’s subliminal radiance creates a feeling of stillness. In In Praise of Shadows, Tanizaki calls it a “pensive lustre”. We’re told it also discourages insects.

On the floor were some delicate calligraphic prints currently in production. In many of the workshops that we visited, artisans had a designated floor space on which to squat for especially delicate work.

Much had been invested without any direct financial outcome. Apart from some repairs, no products were made for sale. The South Korean government pays masters like Hong a stipend of around $USD 20,000 to maintain their heritage skills. Most of his work involves copying annals from the Joseon dynasty, which are already digitised.

What is the value of that?

To answer this question, we need to step back in time. The Joseon dynasty was one of the world’s longest. For nearly 500 years (late fourteenth to the nineteenth century), the Joseon emperors officiated over a flourishing culture, which produced unique technologies such as metalsmithing, shipbuilding, exquisite porcelain and a new efficient alphabet.

The society was based on a Confucian hierarchy: everything revolved around a hereditary monarchy. But there was one safeguard.

A key role in the court was the historiographer. These scholars recorded the court’s activities, including travel, decisions and meetings, as well as observations of customs and the state of the countryside. Their notes were kept secret during the emperor’s lifetime: even he could not read them. One emperor fell off a horse and instructed witnesses that this was not to be revealed to the historiographer. Not only was the accident recorded, but also the Emperor’s instruction not to tell anyone.

Only after the emperor’s death were the records compiled into the official annals of the reign. They were kept in a special building with limited access. Every three years the annals were “aired” in direct sunlight outside, to prevent damage from dampness and insects. A special ceremony would accompany this process to prevent any mishaps.

Books with hanji paper have hooks so they can be hung in the open air to prevent damp and insect damage.

This process is honoured in the UNESCO Memory of the World project, which supports the preservation of cultural records. The walls of Master Hong’s workshop are covered with awards for this program that were produced by himself, using traditional Korean methods.

While South Korea has made dizzying progress in modern times, it commits to retaining its link to the past, particularly the time before the Japanese occupation in 1910. This can be seen in the traditional hanbok costumes young people like to hire while walking around their city on the weekends. Many K-pop artists invoke Korean heritage in their songs.

More broadly, such anachronistic techniques contribute to today’s cultural diversity, especially as digital technology is homogenising cultural production. Younger Cheongju craftspersons find ways of using these techniques in creative ways, as highlighted in the 2023 Cheongju Craft Biennale which featured the creative dialogue between heritage and contemporary.

The process of copying reflects a broader Asian attitude to heritage. While in the West, institutions like museums privilege the preservation of the original artefact, in many Asian cultures it is seen as appropriate to reproduce the original. This can be seen in architecture, such as the reconstructed ancient wall of Xian at the start of the Silk Road, or the Japanese temple in Ise which is completely rebuilt every 20 years.

Copying has a religious value. Traditionally, it was considered meritorious to copy ancient Buddhist sutras by hand. But implied in copying is the impermanence of the original. Tibetal sand mandalas are painstakingly constructed grain by grain, only to be swept away on completion. Continual reproduction ensures that a culture remains alive, rather than being frozen in a museum.

There is a Korean saying, “A dragon rises up from a small stream”. Koreans often return to this small stream to replenish their culture. Rather than falling behind, this heritage propels them forward into the world.

It’s up to us non-Koreans to enjoy this. We can:

- Visit in spring or autumn to enjoy the changing season and beautiful museums across the country, all with free entry

- Plan to attend the Cheongju Craft Biennale in September 2025, curated by Jaeyoung KANG

- Plan to submit an entry to the very generous International Craft Competition, due July 2025

- Browse the archive of previous Cheongju Craft Biennales

- Visit your local Korean cultural centre, such as Sydney’s

- Explore our Mongyudowan garden of stories from South Korea

On the Other Hand is an exclusive article for Garland Circle members.