Bhuj 2022. Having worked in co-design, Adilbhai and Zakiyaben are better able to work together. They always critique each other’s designs; photo: Nevada Wier

In an extract from Judy Frater’s forthcoming book, two bandhani artisans share their journey with Somaiya Kala Vidya to realise their designs in successful careers.

Zakiyaben and Adilbhai, both Khatri artisans, took the design course in 2013, in separate classes as per the culturally appropriate mandate of the program. I observed both classes, monitoring each student’s progress. Zakiyaben’s father’s family did batik. They were known in Mundra for being orthodox and close-knit. Until 2005, the 66 family members lived together. Zakyaben’s father, the youngest brother, was the one less conventional. He treated boys and girls equally and supported Zakiyaben’s education. She excelled in everything. But design was her passion. She learned batik by watching, and did wax brush painting in the workshop when the artisans weren’t around. When she was deemed mature, her father made her a batik studio at home. She also tied bandhani for income and had her own bank account.

After the first course, she said, “My vision and understanding have changed. From sketching I learned to see shades of colors. In nature, I saw how to make harmony from contrast.” After the second course, she observed, “If we use principles, there are many ways to make traditional designs new. Now I will see rhythm, movement, balance everywhere.”

In the fourth course, after visiting a potter’s village, Zakiyaben redefined a trend forecast as “The Magic of Mud.” Working within her own technical limitations, she had decided that bandhani was more feasible for her than batik and experimented with varying sizes of bandhani dots for homework assignments. She applied her experiments to inspiration from the shapes and textures of pots and designed a collection of garments from traditional to Western to suit the contemporary working woman’s needs.

“When we think we know nothing, that is the beginning of education,” Zakiyaben Adil Khatri

Meanwhile, in the men’s course, Adilbhai was charting a parallel course.

Although his family were dyers by tradition, his grandfather was a professor and his father had a government job. His mother tied bandhani for income, and his uncle had a bandhani business. After twelfth grade, Adilbhai decided to learn bandhani from his uncle and quickly wanted to take the craft in new directions. He took the KRV course to increase his understanding and knowledge of bandhani.

Summing up the first course, he said, “Whatever work we do needs effort and perfection We learned all color variations in two weeks! The tint, shade and chroma exercises were fun. I got the desire to do something new.”

After the second course, he said, “When we use principles consciously, we can do something. In nature, I observed that everything is harmony. And nature is the basis of everything.” He made a wonderful fresh piece textured with large and small dots and shibori for homework, for which Fabindia later gave him an order.

The Visiting Faculty for course 3 wrote, “Adil is eager to learn and open to feedback. He understands that he is inexperienced, so he asks questions. He works conscientiously and has good analytical and perception skills.”

“Now I think anything can be done in bandhani.” Adilbhai Mustak Khatri

Adilbhai reinterpreted his trend forecast theme as Dream City. He explored fantasy and pushed as many boundaries of bandhani as he could. “Traditional work can’t be used every day,” he explained. “I want to make new things for new uses.” He became so immersed in his theme that he dreamed his theme board. “In sampling, I realized how much rests on the material. Fabric affects color,” he said.

For his collection, he created airy resort wear garments highly textured with his large and small bandhani dots and shibori. “I chose a theme where I could bring in new concepts and experiment,” he said. “I looked for minimum stitching and maximum texture. I lost mental limitations. Now I think anything can be done in bandhani.” He graduated with awards for Best Collection, Best Presentation, and Best Student.”

These two are perfect for each other, I thought. But as a cultural outsider, I could not say anything. Communities had their own intricate methods for deciding matches.

The next year, we formed Somaiya Kala Vidya and I began the Business and Management for Artisans course. Adilbhai quickly signed up for the men’s course. He wanted to explore new options in design and felt that business was an essential link. However, he did pose the question, in a pilot course, would the students be getting full quality education? Zakiyaben was among the artisans I selected as suited for the women’s course. She was clear from the start that she would continue. “Design is not enough,” she said. “You also need business.” She had considered doing a BBA but decided that the SKV BMA was better because it was focused on craft.

Each BMA student finally made a five-year business plan. Zakiyaben planned to work with women. “I feel excited to work after envisioning my five-year goal,” she said. “Risk is necessary. I will aim for RS 200,000 of product and a profit of RS 25,000 per exhibition. On further reflection, she added, “Through this course, we understood the limitations of a design course. Many women are equipped only to work for others. I realized the importance of ownership and I passed it to the women tiers I work with. I showed them my designs before giving them work, and the finished products after I had dyed them. They were keen to know what sold. I got more respect in the community after doing the course.”

Adilbhai envisioned that Nilak would be a global brand famous for its unique designs. Immediately he would explore natural dyes and focus on domestic exhibitions and online shops. His long-term plan was to explore stitched garments, participate in international exhibitions and workshops, and collaborate with other designers. “Risk leads to profit,” he said. “We learned to prioritize and plan for the long term. I realized that in business it is important to be honest, ethical, and do good quality work.”

Bhuj 2022. Adilbhai has a fascination with Islamic geometry and finds endless inspiration in tessellations; photo: Nevada Wier

Zakiyaben and Adilbhai found each other They were engaged before the BMA was over and married in November 2016.

Zakiyaben moved easily into Adilbhai’s welcoming, casual and comfortable family. They started a joint business, keeping both of their labels: one on either side of their recycled paper bag packaging. They began an ever-evolving collection inspired by Islamic architecture, with a tongue-in-cheek piece inspired by the wealthy Ambani family mansion in Mumbai for good measure. They sold their work to young contemporary designers and established businesses. Their work became technically excellent and refreshingly contemporary. Kutch has hundreds of bandhani artists, and bandhani is ever present in a range of markets. In that scenario, their collections are original and memorable.

[Zakiyaben] inspired other women artisans and in 2018, three women bandhani artisans, and the first woman weaver took the design course.

Adilbhai also realized his dream of recognition. In 2018, he won the Crafts Council of India Kamala Award for Young Artisans -an award created for him to honor his exceptional creativity and the coveted World Crafts Council Seal of Excellence. He went on to receive the first All India Artisan and Craft Workers Welfare Association award for Next Gen Entrepreneur and was selected as an ‘Icon of India.’

In 2019 Adilbhai participated in a co-design project with artisans from Oaxaca. He realized that his partners had different interpretations of the theme they chose, water. “I learned ways of thinking,” he said. “Rina and Miguel were very open. They didn’t think, we are going to produce a collection, so we do this and that. They did whatever naturally came to their minds. This kind of collaboration lets artisans go beyond their limitations.”

I asked if he would now produce the collection he had made. He flatly said no.

No?

“This is work for a market that understands and appreciates design,” he said.

The market to which Adilbhai and Zakiyaben have access is pop-up exhibitions and shops operated by craft organizations in India. They feel that for these venues people expect what is already in the market. So they always take traditional designs in red and black, and whatever is currently already in fashion. They have questions about marketing bandhani. “Should craft be mass produced?” Adilbhai earnestly asked. “I mean, if the same design is replicated in 2,000 pieces or 3,000 meters is it going in the right direction? And when we make a new design should we protect it or show it to the world?”

Adilbhai and Zakiyaben were juried into the International Folk Art Market | Santa Fe in 2020 and again in 2022. They had two opportunities to experience a higher-end clientele, and for the second show, Adilbhai sent some of his water collection, blue bandhani with patterns of drops and waves. Their work was appreciated, and they earned more than they could in India. Sadly, due to covid-19, they were not able to attend.

But in 2022, Adilbhai traveled to Oaxaca to conduct bandhani workshops, share his co-design experiences, and meet partners Rina and Miguel. Opportunities to explore international markets, virtually and personally, were important for both Adilbhai and Zakiyaben in establishing identities, and in enhancing their understanding of the value of bandhani.

✿

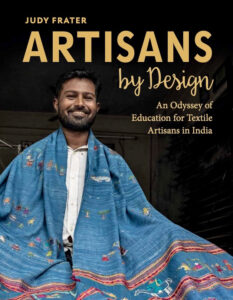

This is an extract from Judy Frater’s book Artisans by Design: An Odyssey of Education for Textile Artisans in India, to be published with Schiffer Publishing LTD on October 28, 2024. Artisans by Design chronicles the journey of developing the first design school for artisans in India and fifteen years of artisans learning design. Spanning 50 years, the story is told in vignettes of artisans who were part of the journey, intertwined with the author’s story. Through this dialogue, the reader experiences what happened, how and why, and what its impact has been on traditional artisans in the contemporary world. A rare, intimate portrayal of artisans, the book offers personal connections to people usually glimpsed from a distance and insights into tradition, craft, and the creativity of traditional artisans. It provides textile aficionados and people concerned with sustainability an authentic, fresh approach to development, illuminates sustainability as cultural heritage and presents development as human-centered.

This is an extract from Judy Frater’s book Artisans by Design: An Odyssey of Education for Textile Artisans in India, to be published with Schiffer Publishing LTD on October 28, 2024. Artisans by Design chronicles the journey of developing the first design school for artisans in India and fifteen years of artisans learning design. Spanning 50 years, the story is told in vignettes of artisans who were part of the journey, intertwined with the author’s story. Through this dialogue, the reader experiences what happened, how and why, and what its impact has been on traditional artisans in the contemporary world. A rare, intimate portrayal of artisans, the book offers personal connections to people usually glimpsed from a distance and insights into tradition, craft, and the creativity of traditional artisans. It provides textile aficionados and people concerned with sustainability an authentic, fresh approach to development, illuminates sustainability as cultural heritage and presents development as human-centered.

About Judy Frater

Ashoka Fellow Judy Frater lived with artisans of Kutch for three decades, where she founded Kala Raksha Trust and Museum, Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya, the first design school for artisans, and reinvented the school as Somaiya Kala Vidya. She has been honored with the Sir Misha Black Medal for Design Education, the Crafts Council of India Kamla award, the Designers of India Design Guru Award and more. Previously Associate Curator at The Textile Museum, author of Threads of Identity: Embroidery and Adornment of the Nomadic Rabaris, and The Art of the Dyer in Kutch, she has written and lectured extensively on craft, and has an over 8,000 following. She now lives in Santa Fe.

An Unforgettable Textile Experience: 4 day-long workshops and more

5-18 January 2025

Celebrating her book, Judy Frater is taking a small group to Kutch to meet the artisans profiled and explore hand-crafted textiles from the eyes of the artisans who create them. She will bring you into the lives of traditional artisans today. Meet artisan design graduates, hear their amazing stories, enjoy their exquisite innovations, and learn incredible techniques. Be prepared to ponder concepts of sustainability.

Contact Judy Frater judyf@textileslive.com