Being born Hindu, I often wonder if I am living each day consciously. Although the metaphysical concepts of awareness may seem removed from craft, I have begun to realise that the two are hardly isolated from one another. Using one’s hands to make something requires us to bring our entire presence to the act of creation.

Surely, Gandhi must’ve thought long and hard before he made the charkha (the spinning wheel) the symbol of our country’s freedom struggle. From a political and economic standpoint, I am quite certain mobilising homeland resources must have been a priority and a smart thing to do, but surely a man like Gandhi thought on a completely different plane than the rest of us. There is much debate among my peers about the man himself. But among the so-called trailblazers of today, it’s often a fad to have a “different point of view.” My generation is certainly one that knows Gandhi only through history, therefore speaking only as a voice of my times I would like to bring out a rather bold comparison between two personas that had a profound effect on the twentieth century.

Despite their diametrically opposite values, Gandhi created every bit of a mass hysteria similar to that of Hitler’s. It is sobering to know through their examples, the great good or evil that mankind is capable of and the way in which he/she can apply their minds to achieve goals. The charkha became a symbol of hope for a new world. How does one man get millions of people to sit down at a spinning wheel and create with their hands? I think in no way should this act be belittled. Firstly, it took little to make a charkha. Any man or woman could make one using wood, wire and simple tools. India, primarily an agrarian economy was rich in cotton, livestock and manpower. Gandhi played on the strengths of the nation. He capitalised on the fact that Indian women, innately skilled in handicraft, could easily spin during their spare time off the fields. Great ideas only work when they account for the privation of the people and the need of the times.

So not only did he make people express their plea for freedom through creative action, but he even created a uniform that symbolised the movement. Khadi (handstand and handwoven cotton textile), made by the hands of the very people who wore them, became the material of mutiny—quite literally. He showed us that, without words, one could convey a strong message to the world. I imagine, if I lived in the times of pre-independence and I were someone who wanted to protest, I didn’t need to fight or rally or walk down the street protesting, I could simply join the masses of people spinning their charkha. I had only to put on my khadi shirt and I was part of something much greater and bigger than myself. I imagine my hands would draw my mind into the purpose of my actions. To me, Gandhi’s simple khadi spinning and satyagraha (non-violence) movement is one of the greatest cults the world has ever witnessed. It spread like wildfire and communities in every village across the country began creating khadi together in the fervour and hope of freedom. He mobilised every man and resource into this action. The ideas of non-violence arise from awareness, a deep awareness of the self and the powers it holds to create or destroy. The man was so pragmatic and so simple. In a world more obsessed with show-biz, surely we have lost Gandhi along the way.

I live and work in rural central India. We are quite removed from the modern world. We are located in the middle of the country, in the rustic surrounds of Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve where my mother runs a tiny crafts establishment. I also work at a Visual Arts Centre, Art Ichol, from where one can quite easily access the remote villages that often feel like they are nestled at the far ends of the earth. We have smaller community development projects in villages around Ichol. One would consider it rather surprising then that I had really not found any local weaving in the area for the last couple years. On a recent collaborative research residency Disappearing Dialogues at Art Ichol, ideated by artist Nobina Gupta, we had four textile designers studying the local area and its textile practices. Although Madhya Pradesh is quite famous for its bagh print, maheshwar and chanderi textiles and its organizations like Bio-re, we were quite certain that around the immediate area of Ichol there was no such practice of print or weave in existence.

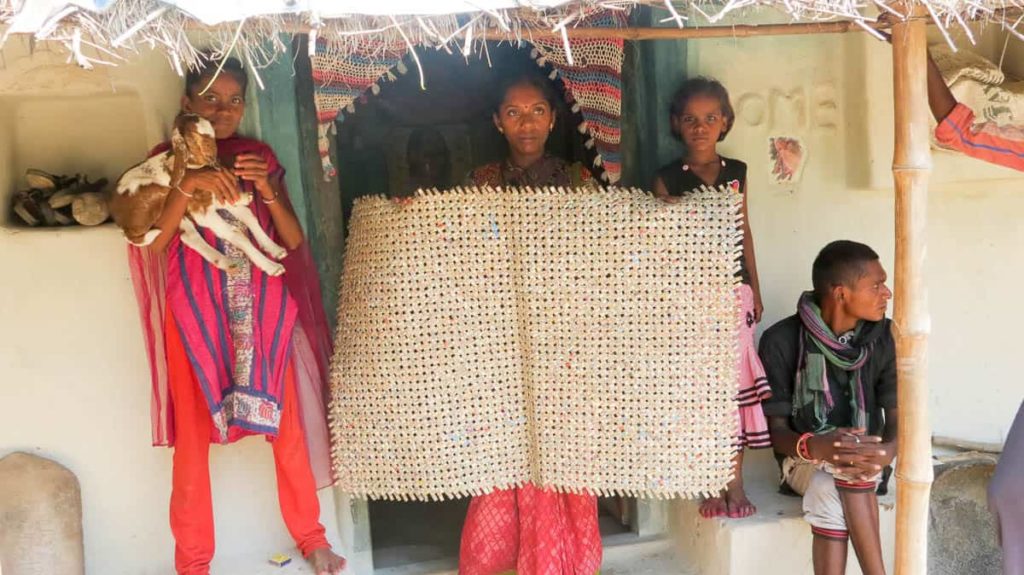

In order to conduct research and study on the local textile, we had to go further afield. It seemed that this part of India, in its race for industrialisation, had lost its traditional weaving practices. Readymade garments of synthetic fabric were found in the homes of the villagers. There were a few women who were quite effective at transforming waste cloth from old saris and textile waste into little rugs and odd creations of that sort, but there was no real crafting practice. Another village had a rather interesting floor mat woven from collected plastic Paan Masala packets that had been found littering the place. They were quite fabulous, but these inventions and instances were too far and few. We hadn’t hit the jackpot yet.

I mulled about how we were going to guide the textile group into their field work. I was stumped. I had been thinking that, despite his assassination in 1948, Gandhi would always be alive in his ideals. But it seemed he had finally died. I had three of the four textile experts who weren’t from India and they had come all the way here hoping to find India’s rich crafting heritage, but… has it all vanished from this area? I always thought great concepts were timeless, but we seem to be losing those practices that make India a nation of great heritage. In the thick of the residency, I found it rather poignant to ponder on these thoughts. After all Disappearing Dialogues was a call to value and preserve traditional practices of organic farming, brick making, forest rejuvenation, art, craft, textile, stories and alternate techniques of sustainable living. What if there’s nothing left to preserve?

As we discussed our ideas and findings, we talked about how change is inevitable. Questions arose and we felt that perhaps something is lost, but does it necessarily mean that nothing of value had been taken forward? Then, a couple of days into the residency… a breakthrough. We met Shamendra Singh, from the royal family of nearby erstwhile state of Nagod. Vini, as he is fondly called, is an avid conservationist who devotes his time to various welfare projects in the area. He tipped us off about a rug making tradition in the area that none of us had ever heard of. Vini mentioned that goat and sheep herders of the area made special winter rugs and that these were perhaps still being made today. We wondered why we had never seen these rugs in the villages around here. In any case, this was definitely worth exploring.

After asking around, the very next day we set off on an adventure to find the mysterious rug that had eluded us thus far. It took us an hour to get outside the mining belt of the area before we drove through the first village. Nestled at the base of a ridge, we asked around for the goat and sheep herders, but no one quite knew what we were looking for. Some knew about the rugs, but much to our chagrin they told us we wouldn’t find them anywhere here. Four villages and several winding dusty outback lanes later, we stumbled upon a lone herdsman with a flock of sheep. To us, this was nothing short of striking gold. It got us ticking and the herdsman said we were on the right path, but we had to venture further on. I didn’t know it yet, but we were to uncover an entire community living in one village, all of whom were herders and weavers. In fact, the village was called Surkhama but nicknamed Ghadhariyaan (Place of the Herdsmen). As we neared Surkhama, I noticed a lot of things changing. The road turned to a mud path. There was no sign of plastic anywhere. The mud homes were neat, clean and beautifully patterned and painted by hand. Doors were ajar and you could peek right into the homes of people. Grain had been left in the middle of the road for cars to pass over and thrash the husk apart. It almost felt here there had been a reversal of time, yet it truly seemed a peaceful and idyllic paradise.

Upon arriving at the village, we approached a rather modest home, just the second door we passed. Outside the entrance were huge baskets overturned with half a brick on top keeping the baskets firmly rooted to the ground. Under them two day-old kids curled up, feeling secure in their makeshift shelters while the adult goats were away grazing. Seeking permission to enter, we explained to the head of the family who we were and why we had come. Already we were ogling at the simple spindle lying in the little courtyard, wondering what kind of rugs this could whip up. We hadn’t yet noticed any looms that usually sit in the porch of homes, as you would in other parts of India.

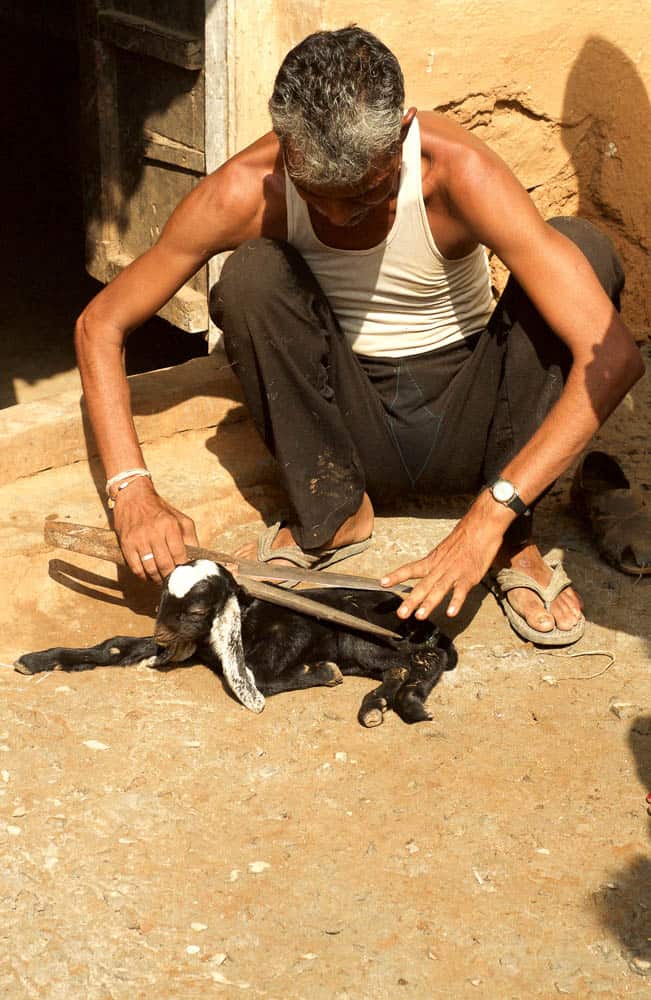

As he brought out the woollen rugs, there was a gasp. They were huge, about four and a half to five feet wide and six feet long, simple in design, yet elegant in three or four neutral colours lined by bright pink borders. He showed us his special set of “shears” used to cut the wool off the sheep. The wool was then fluffed up with what is best described as a bow. The hair was separated by strumming the string of the bow between the wool, making it separate. It was then rolled into oblong cocoon-like balls and stored for spinning. Next came the spinning of the wool into yarn and to my surprise that feeble looking spindle was more than capable of twining the wool. The loom itself was hardly two feet wide. So compact and portable, it could be stowed anywhere. It was no wonder we hadn’t been able to see them. The weaver sits atop the loom and uses various wooden slats to overturn the warp after each weft. They are woven into long panels or runners and four or five of these are then joined to create the final rug. Some villages made smaller bathmat sized rugs that are used by people while sitting on the floor for puja (religious ritual) and worship.

- People of the village community, photo by Tanya Dutt

- Rug ready, photo shot by Nathan Crotty

- Neutral Colours of the rug, photo by Nathan Crotty

- People of the village community, photo by Shatarupa Thakurta Roy

- People of the village community, photo by Shatarupa Thakurta Roy

- Woman spinning by Shatarupa Thakurta Roy

- The process of making waste plastic mats as shot by Nidhi Khurana

- Demonstrating how the shears are used, photo Nathan Crotty

- Barkat holding up a rug for us to admire, photo by Nathan Crotty

- Simple wooden Slat Loom, photo by Nathan Crotty

- Rambhai as photographed by Nathan Crotty

- Close up, photo by Nathan Crotty

- The recycled plastic and mat weaving women as photographed by Nobina Gupta

- Spinning at the Charkha by Sandeep Dhopate

- Shy kid by Tanya Dutt

So, why had we never seen these rugs in use and where were they sold? They told us the rugs are multipurpose and double up as carpets, floor mats, rugs, blankets and mattress warmers. It would be hard to spot one because they weren’t sold in conventional markets or shops, but were traded with farmers, who bought them from the weavers directly. Often old saris are used to cover up the rugs to ensure they stay clean and for better longevity. Usually one lasted for years, so you wouldn’t need that many. What struck me was that start to finish, including the shaving of the wool, the rug was completely made by hand. There was absolutely no mechanized process in this—zero. It may not have seemed so, but I had the sense that perhaps the villagers had a better quality of life in terms of the produce they consume, the lifestyle and a quality of living that comes with an immeasurable value, one that came from a life completely generated by human touch. Even the air and environment was visibly cleaner here. I felt wonderfully lost in this village, I felt like I had never known the modern world. As if it had never existed, here everything was truly and fully alive and aware. And when I asked the maker about what he felt about the rugs, his eyes sparkled… “Well we use them ourselves; after all it is the way of Gandhi.”

Author

Tanya Dutt is the Outreach Manager & Coordinator at Art Ichol. She wrote her first poem about a cat at the age of ten and since then discovered her penchant for the pen. An avid nature lover, her heart pursues the bounties of the world through various cultural projects and travels.

Tanya Dutt is the Outreach Manager & Coordinator at Art Ichol. She wrote her first poem about a cat at the age of ten and since then discovered her penchant for the pen. An avid nature lover, her heart pursues the bounties of the world through various cultural projects and travels.

Comments

Very well written with detailed description and information. I am so proud of you.

What a journey and in conclusion to be so beautifully rewarded. Lovely story Tanya, thanks

This is a lovely story. Thank you so much for sharing it

Great article Tanya, really interesting about the rugs. Hope to see them some day.

Wonderful…!

Loved the start and the ending highlight that brings to the forefront the true meaning of life on mother Earth. So proud to see the real side of my beloved country being portrayed in the most befitting setting and through the perfect view point. Joy guru to that Tanya!