I first met Jenny Crompton at MARS Gallery during NAIDOC week. Her drawings of baskets impressed me with the beauty and simplicity. They also resonated with Robyn McKenzie’s experience of string figures and confirmed how fibre work sometimes finds it easier to enter the market in two-dimensional form. I was curious to learn her story and wrangled an invitation to visit her studio in Bellbrae.

I ventured into the land of “sea change”. For us metropolitans, winter on Victoria’s surf coast suggests the dream of living a life in a part of the world otherwise limited to a few summer weeks of annual leisure. And so our dreams become commercial opportunities. The bus from Geelong station passed shopping malls dedicated to the burgeoning surf industry around Bell’s Beach. At the end of an unsealed track winding towards the coast, I eventually found the house Jenny shares with her husband and son. After a boisterous canine reception and welcome coffee, she began the tale of how she came to be there. Her story unfolded with ever increasing poignancy.

Jenny Crompton’s tale began as a student, when she was pushed into business studies. It wasn’t a good fit. She preferred acting and took classes after hours while bookkeeping during the day. However, acting didn’t work out and she spent three months travelling across Europe looking for an alternative in life. Eventually, she reached Barcelona and encountered the work of Gaudi. She was duly inspired to start making mosaics on return to Melbourne. Jenny felt at home with this way of working: “My hands work better this way (moving hands towards each other), rather than this way (one hand drawing)”. Within a month she had an artwork for show. Then she set up tent behind her home in Melbourne’s western suburbs and took on large sculptural commission work.

- With Hari in Sumatra

- With Hari in Sumatra

- With Hari in Sumatra

One day, her husband bought her a book on Southeast Asian jewellery—“The page kept falling open at Sumatra”. Mosaics turned out to be back-breaking and the possibility of a change of scale was appealing. They travelled around Indonesia for six weeks and ended up in Lake Toba, North Sumatra, where she met Hari, who was not only a local datu or spirit man, but also a canoe and flute maker and singer. He taught her wood carving, “Hari didn’t speak English. I went to the market and bought a knife and they all laughed because I accidentally had bought a vegetable knife. I then bought a hand forged carving knife, which I still use today, and a block of cedar, and thought, ‘Oh this is a bit hard’. So I just sat in the carving workshop with the woodcarvers watching and trying to learn their craft, amazed at their skill and technique of Batak carving. In the end, Hari became my teacher, and after three weeks, I finished my first wood carving. I just loved it.”

After Lake Toba she trekked through the Mentawai islands, where she witnessed the indigenous culture of the islanders, and an animist way of life dependent on the jungle. Their day to day practices of gathering and the use of plants and animals greatly affected her.

Back in Melbourne, she concentrated on large-scale sculptures that were influenced by these travels. Her shapes were inspired by Sumatran jewellery and plants. A few years later she returned to Indonesia travelling through Sumba and Flores and found something quite special on the island of Lembata. The traditional whaling village called Lamalera is located on a cove with black volcanic sand. She recalls the scene at night, when the large white whale board scattered across the beach were illuminated by the full moon. There was something magical in that landscape, evoking a close connection to death. She was inspired to create again with Hari.

- Jenny Crompton, Mamuli

- Jenny Crompton, Mamuli

This time, Jenny was inspired particularly by amulets called mamuli from Flores and Sumba. She reconnected in Sumatra with Hari and carved a large kinetic work, Mamuli. But impressed as she was with Indonesian culture, she was increasingly aware that it wasn’t her own.

Back in Australia, a distant relative made contact with the news about her family history. It turned out that her great, great grandmother Min was a Wadawurrung woman. She had a daughter with a Scotsman who left her, to return to the home country. The daughter was taken away and raised by her Scottish uncle. At one point, she took a boat to Scotland to find her father, but she was rebuffed and sailed back to Australia.

- Jenny Crompton, Collecting kelp

- Jenny Crompton, Sewing kelp

- Jenny Crompton, Coolamon with beaked mussel and barnacle

After finding out about her Wadawurrung heritage, Jenny and her family moved to Victoria’s surf coast, which is on Wadawurrung country. Without knowing it, Jenny had already been sourcing material from her ancestor’s land. Now her art practice is focused on collecting and gathering seaweed, kelp and other found materials from this coast. Her technique with seaweed seems original and involves moulding the seaweed using a PVC solution. “Finally I developed a technique, where I could use these fragile plants and make sculpture forms from the fibres.” I recognise nothing familiar in the processes she is describing. Every step is painstaking trial and error. What results are transcendent works that transform the mundane world into something quite radiant, “My work with the seaweed is about transparency, and seeing the fibres of these remarkable plants”.

- Jenny Crompton, Seaweed flower

- Jenny Crompton, Gathering at Godocut (front)

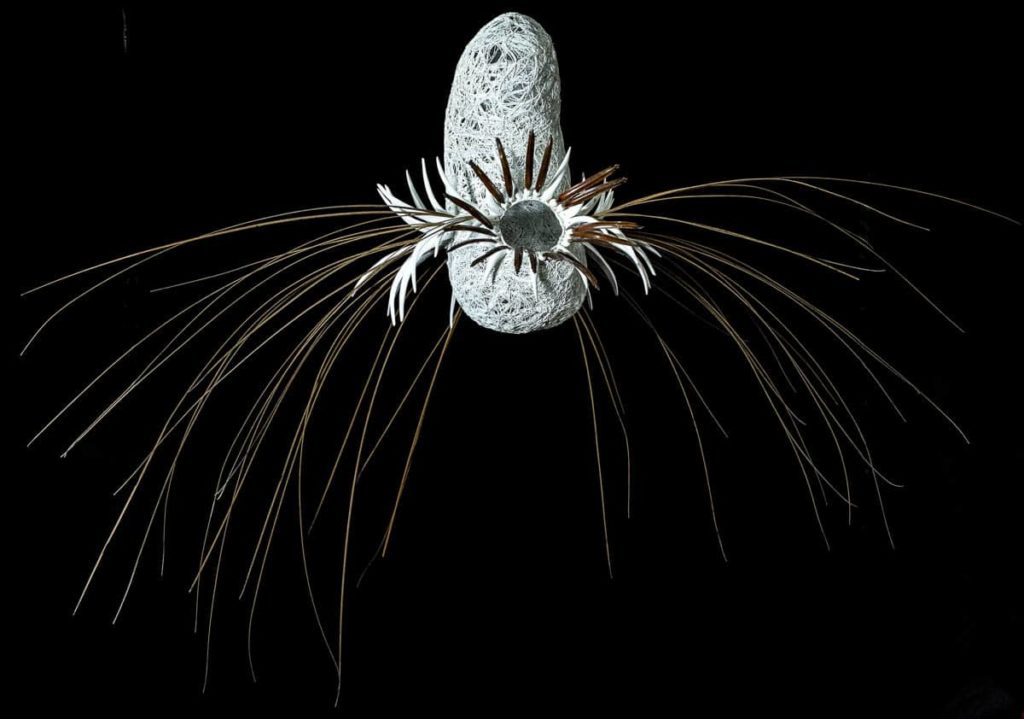

- Jenny Crompton, Sea country, spirit pod, Lorne

- Jenny Crompton, Sea country, galah nest, Lorne

- Jenny Crompton, Sea country, min-murrup, Lorne

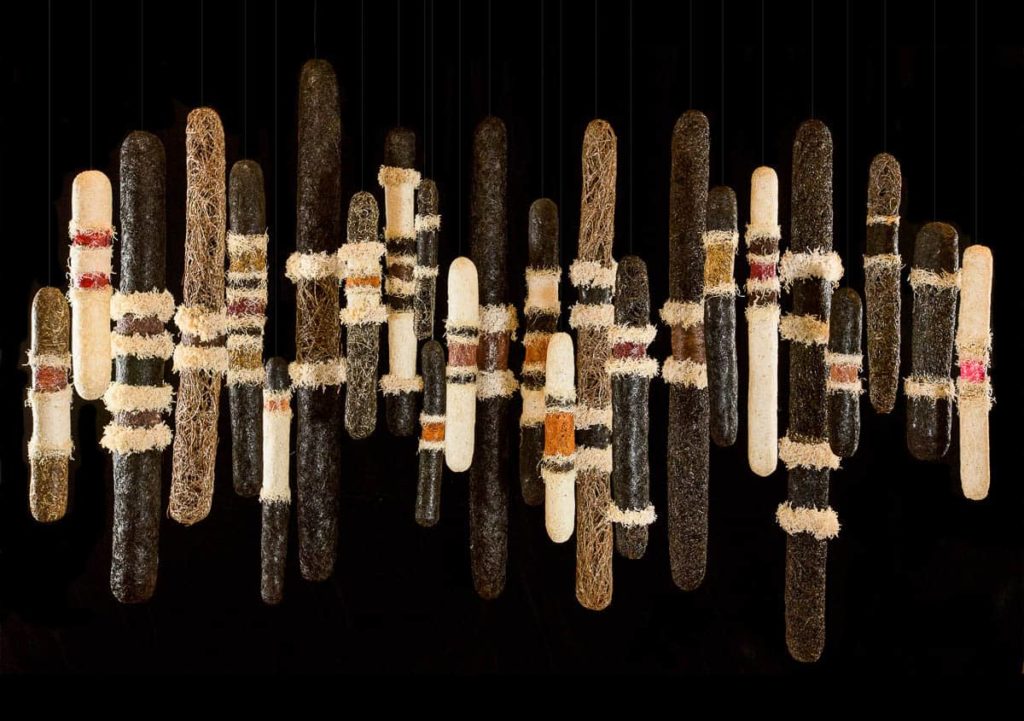

- Jenny Crompton, drawing

She’s now found a confidence with her art practice and a connection to her own Country. In 2014, she won the Deadly Art Award at the Victorian Indigenous Art Awards for her seaweed piece Gathering at Godocut. In 2016 she won the Lorne Sculpture Biennale, Trail Award, and the People’s Choice Award with her work Sea Country Spirits. The work took nine months to create and was inspired by the land, sea and sky. It included a sculptural installation of 32 hand sewn copper wire shapes, sprayed white, as well as found objects from her collecting over the years feathers, tree grass stems, driftwood, shells, which were sewn back into the shapes.

She is far from resting on her laurels. Jenny shows me a treasury of other found nature that she has been stockpiling from her walks. She likes to break things down into components that she can repurpose into sculptural forms. She is currently mould-making, using dissected kangaroo bones, which come in a myriad of oval forms.

I feel I have taken too much of her time. She is racing against a deadline eight months away for an exhibition at Koorie Heritage Trust, where she has a residency. But she insists that we take an imaginary walk through her planned exhibition. It’s a wonderfully ambitious installation, with floating shapes reflecting the waterways of her recovered country.

Maybe surfing is a good metaphor for her career thus far. Life has risen up with its challenges, sometimes dumping her, but eventually, she found a wave to take her home. Impelled by the animist cultures on Australia’s doorstep, Jenny Crompton has given new and wondrous form to the ancient spirit within.

Author

Kevin Murray is managing editor of Garland. Since taking up the Writer in Residence program at the Meat Market Crafts Centre in 1990, he has been dedicated to advocating the value of studio craft to a broad audience through writing and curating.

Kevin Murray is managing editor of Garland. Since taking up the Writer in Residence program at the Meat Market Crafts Centre in 1990, he has been dedicated to advocating the value of studio craft to a broad audience through writing and curating.

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.