In an old cardboard box on the concrete floor of Sandra Bowkett’s studio there is a huddle of raw-looking chai cups. They are Indian by design and were made by an Indian potter. What are they doing here in rural Victoria? Are they out of place? There are certainly no chai-wallahs (Indian tea-sellers) to be seen nearby.

The cups are plain little things, dry and dusty, without handles, and they are piled one upon the other without fuss. They call for liquid and lips, for people to drink from them. After use they can be crushed underfoot, back into the earth they came from, for they are cleverly made to be disposable in a dust-to-dust sort of way.

The chai cups were produced by a young man from a potters’ colony on the western outskirts of New Delhi. His name is Banay Singh and he can make about 100 of the cups in an hour, spinning them off a monstrously heavy wheel. That’s his job. The colony’s other potters make a lot of other stuff: water jars, flower pots, biryani pots, lassi cups, money-banks, Diwali lamps and ritual containers for various occasions. It’s their livelihood and their niche.

Banay Singh made chai cups when he came to stay with Bowkett in 2013. He is one of several of his fellow townspeople who have done so at Bowkett’s invitation since 2002, when she first visited the potter’s village, called Kumhaargram. Since that beginning, Bowkett has made many trips to Kumhaargram and arranged for the visits to her studio and home at Tallarook, a hamlet just outside Seymour. There and elsewhere in Australia, the potters do workshops at schools and other venues, to make objects and pass on skills—a program that is formally called Crosshatched. Bowkett observes that she has gained far more than she thinks she has been able to give.

What inspired her to bring these potters all this way across the sea? Being an adherent to the ceremony of tea—coffee interests me little—this tale of tea-cup makers has great allure. I sit with Bowkett in her studio to explore this, wishing that I—a person who loves experiencing and writing about the visual arts—had known about Kumhaargram during visits to India. In Bowkett I see what I thrill to discover in artists: a desire to ”Only connect!”, the epigraph E.M. Forster famously wrote for Howard’s End. Those two words conjure a need to go outside comfort zones, geographical space and cultural familiarities in a bid to find common human qualities that link us all, in this instance through art-making. A first clue to Bowkett’s deep sense of this can be found in another sort of handle-less teacup warming up on her wood-stove. This cup is one she made herself and it is a beauty: honest, earthy, lovely to hold and to sip from. She is, after all, a person whose hands have been meddling with clay since the 1970s, so she knows a lot about vessels—bowls, pots and, of course, cups.

Some people look at tea leaves for answers, but with Bowkett and her Indian visitors it is best to start with both her cups and Banay Singh’s. There is more to them than practical usage: they contain pointers to the deeper interests at work between Bowkett and the potters she has met. These cups infuse a balance of functionality and pleasing form that puts us at a certain ease, not necessarily in a conscious way, by bringing us into the here and now. They become fluid extensions of the body. They express hospitality and connection. Hold, sip gently and inhale the fragrance.

Chai is the Hindi word for tea, but masala chai is what most of us know—the spiced, milky and immensely sugary decoction that has strong hints of cardamom, cloves and cinnamon, as does pretty much everything else in sense-stimulating India. When masala chai made its way to Australia—probably in the 1960s or ‘70s—it would have seemed a hippie alternative to the British-style tea long entrenched here since European arrival. Bowkett enjoys Indian chai, but she’s grateful that when she was at Kumhaargram her hosts would offer it in the little chai cups that hold just a few mouthfuls; just enough to not become overpowering. “When you enter an Indian household, they’ll offer you water and then tea,” Bowkett says. “Chai is something everyone can afford to offer. I always accept.”

It is part of a social process: “Someone else will have the tea with you. I think what happens in our culture is we tend to get down to what we are there for pretty quickly. That doesn’t seem to be the way with the families I know in India. Usually it takes an effort to get to where you are going. Sit there, collect yourself, have tea… By the end of a morning or afternoon I would have had it [chai] four or five times.”

At her studio, she offers guests English Breakfast tea, or something of that ilk, poured into her own lovely cups from a thermos. India, England, tea, tea-cups: it was the British who brought the tea industry to India, using plants and production methods they had acquired from China. Now, India is the world’s biggest tea producer and most of it is consumed within its borders, where 1.2 billion people live. They drink their chai in cups ranging from small glasses to flimsy plastic cups to traditional terracotta items. All of this is predicated on the complicated roots of an industry that stretches back into the nineteenth century and was initially implicated with the Chinese opium market, Britain’s sugar surplus and a lot of other political, economic and geographical factors. Yet still, I’m as likely as anyone to romanticise the grace and ceremony of taking tea in dainty cups with saucers.

- photo: Sandra Bowkett

- photo: Sandra Bowkett

- photo: Sandra Bowkett

- Vimla finishing the dya kiln, photo: Sandra Bowkett

- Creating a kiln to fire little lamps, photo: Sandra Bowkett

- photo: Sandra Bowkett

- photo: Sandra Bowkett

- photo: Sandra Bowkett

- photo: Sandra Bowkett

- photo: Sandra Bowkett

- photo: Sandra Bowkett

The expanse of ocean

A different sort of cultural exchange is at the heart of Bowkett’s pursuits in India. Generous and warm, Bowkett goes out of her way, despite knowing little Hindi, to understand the different ways of thinking, seeing and doing in India. I see it as empathy in action—engagement, courage and a choice, fundamentally, of loving kindness over fear. The chai cups are cultural bridges.

When Bowkett visits Kumhaargram and arranges for one or two potters to come back to Tallarook, the idea is that they do paid pottery-related work via the workshops and other activities. It’s an opportunity for her and others to engage with these potters on an equal footing. The visitors get some decent income that considerably improves life for themselves and their families; relationships are built; Bowkett and others learn new skills and approaches; and the workshops disperse the Indians’ expertise within Australia.

Bowkett is a kind, no-nonsense and forthright person and these qualities make sense: she is, after all, a maker of simple, beautiful things we can use, so she thinks deeply about what objects such as cups and bowls can offer in our daily lives. That’s not so for most of us: we Westerners of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries seem to think we need ever more stuff. It is as if our world has turned into a giant Ikea store and we are lost in a maze of misplaced desire, boredom and acquisitiveness, where we cannot find the checkout so we go on filling our trolleys. Outside, the waters rise, resources dwindle, storms gather and people without safe homelands make appeals for succour. Slowly, we are being drawn into a sort of North Pacific Gyre, a swirl of oceanic flotsam that will drown us amid our possessions.

Most objects we create are intended to make our lives easier, some are just to fill up space, but occasionally we produce objects to be used that also enhance the beauty of life. The art and craft involved in the making of such objects can be a powerful crossing of cultures: we might never fully understand another culture, but connecting through artful making can vastly enhance an attitude of empathy and open-heartedness.

Such considerations might seem a luxury given the lack of basic necessities—sustenance, clean water and shelter—Western visitors see when visiting India. As Bowkett’s story of her relationship with India emerges, so too does the way her interactions connect deeply with those persisting crises of twenty-first century life concerning the environment, compassion and consumption. Our planet is echoed in the cups made by Bowkett and her Indian visitors. Both planet and cups are earthen vessels wrought by fire and containing the water of life, things that must be held carefully in our hands so they don’t shatter.

Look at Bowkett’s hands, as she selects chunks of wood to toss through the door of her wood-stove: I thought they would be dry, cracked and a bit ruined after all these years of making ceramics. They’re not. This 60-year-old holds them out for inspection: I wonder if somewhere in the little cross-hatchings on her palms there are pointers to what drives her to return to Kumhaargram (a Hindi name which roughly translates as “potters’ colony”). She says her first visit there was thanks to a connection forged by an acquaintance who had been working in the town for a non-government organisation. Bowkett arrived with only a vague idea of what she would do in this town of about 700 families of potters. She certainly had no inkling of the long-standing relationships that would evolve and affect her so much.

The fall of tears

- Asialink Residency, teamthrowing with Manohar Lal

- Manohar Lal on stonewheel, photo: Bridget Bodenham

- Minahar Lal beating out a matka, 2011

As she describes her first meeting with one of her repeat visitors, a man called Manohar Lal (Manori), Bowkett’s eyes suddenly gush with tears. She says she’s “a crier”. It was 2002 and near the end of her initial visit when she met Manohar Lal. She was staying in central New Delhi and travelling an hour each day to the potters’ colony and engaging with the people in various ways. There were three boys who’d hang around her workshops and one took her home to meet his family, including Manohar Lal, his father. “It is interesting that I feel so emotional about it,” Bowkett says, wiping her eyes. “Just walking into their space, there was something different.”

Bowkett says she didn’t feel comfortable with the neediness of some of the people she met at the colony. “But Manori. He was happy I was there. He was confident in himself. Without knowing anything about him I thought ‘this is the man to come to Australia’.”

Bowkett found it uncomfortable to be in the privileged position of asking someone “do you want to come to Australia?”—something the potters might only daydream about, if that—but she did. In 2003 Manohar Lal, another potter called Giri Raj Prasad and cultural interpreter/manager Josephine Sharoha came, helped by funding from the Australia-India Council. “It was a pretty mind-bending five weeks or so,” Bowkett says.

Her initial plan when she arrived at the colony had been to work with a group of women to get them to make decorative objects they could sell independently to generate income. For various reasons, this became unrealistic and she realised how naïve she’d been. “I was really disempowered in a lot of ways without any [Hindi] language.” Eventually, she realised the best course was to invite someone from the colony to Australia and somehow get them earning for themselves—she did not want to be in the awkward position of paying people’s way. She was conscious of subtleties concerning dignity and self-esteem. She didn’t want people feeling any obligations.

In the lead-up to that realisation, Bowkett had increasingly become aware of how much freedom she had in her own life back in Australia, compared with that of her hosts. “I can go to India and work for five weeks. For them, choice is limited. But I could see they had work, they had families, they had spaces they could work in. Very humble living circumstances—but they had their craft.”

Manohar Lal and others have since visited several times. In 2012 during her Asialink residency, one intention of the trip was to identify a kulhaar potter—a maker of small vessels—to come to Australia. This is how she met Banay Singh, and it is more cause for emotion.

“Each morning, on my way to work at Manori’s workshop, I’d pass this corner where this family lived,” Bowkett recalls. “It was a bit of a lean-to off the side of a building and it was dark and I could see this elderly woman just perched on this seat like a little bird. She’d say hello and it was obviously her son working there. He wasn’t even confident enough to look up and say good morning. From early on I thought he was the one I’d like to ask. But I just didn’t think he’d be up to the challenge of going to another country. It came to the end of the three months and I thought it was him I’d have to ask and maybe by then he may have been ready.”

A translator helped when the time was right. Banay Singh told Bowkett he was “the poorest potter in the village”. “But he came. The poor guy. He was sick flying—still so totally lacking in confidence.” Manohar Lal was with him and eased the way across the oceans and into the countryside.

“He was a lovely young man. He has this wonky eye and even in the time he was here having enough food, not having the stress of family life, it almost seemed his eye wasn’t as wonky. He has now moved from that place [the lean-to] and he is just a different person. The power of valuing what he does: that is another thing about them coming to Australia. When you are one of, say, 700 potting families and you are making the lowest grade object, your self-esteem would probably be reflected in that situation.”

The water of life

It was in Bowkett’s studio that Banay Singh made the cups now stored in the box on the floor, ready for sale. This studio, like the potters’ ones at Kumhaargram, is hardly grand. Actually, it’s more like a little shed and it is tacked on to a bigger, messier one that belongs to Bowkett’s partner Peter, an architect. It’s a place for working, hence the lack of comforts. Outside and down the hill a little creek gurgles noisily—there’s been a lot of rain in this usually dry territory this year—and you can imagine dipping one of Bowkett’s bowls or Banay Singh’s chai cups into the fresh, cool water for a drink. Or, perhaps, an Indian water-carrying vessel would work. There is a large one of these in Bowkett’s studio. It is a spherical shape with a lip.

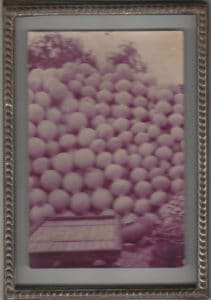

During a visit to India in the 1980s, Bowkett had a significant moment of connection with the work of Indian potters when she saw a mountain of these water pots in Udaipur. Amid all the colour of saris and turbans and trinkets, it was this enormous pile of terracotta-coloured pots that arrested her, an image that has stayed with her and fed her connection with the country.

“As a maker of pots, seeing such an immense volume of these things, seeing how high it was—structurally it was a feat. The thing that really captured my imagination was that there was this one very small pot within the big pile. If that was taken away, the whole lot would tumble. It was the key to the stack.” She loves the form of these large water pots, the beautiful completeness of the shape, the functionality and its volume.

It is little wonder that water trickles through the whole tale of Bowkett and the Indian potters, given the primary role played in India by the Himalayan mountains, their glaciers, and the river Ganga (Ganges). That massive ecosystem, like most others in the world, is now perilously in the balance and likely to plunge into chaos before too long. The Guardian reported last year that most of the 5500 glaciers in the Mount Everest region will disappear or drastically retreat as temperatures increase with climate change over the next century. This will have dire consequences for farming and hydropower generation downstream (more than 400 million people depend on it for their livelihood).

The Ganga is, and always has been, equated with life. Hindus worship the river as a goddess and in Varanasi, the ancient spiritual heart of northern India, millions of pilgrims visit each year seeking purification in the Ganga waters or to cremate loved ones and throw the ashes in the sacred river. It is more than 2,500 kilometres long from the western Himalaya to the Bay of Bengal and was ranked as the fifth most polluted river of the world in 2007. Massive volumes of pollution include domestic waste, untreated industrial effluent and cremation detritus. More than three billion litres of mostly untreated sewage enter it each day. As for the cremations, they are fuelled by vast amounts of tree timber. Fewer trees means less carbon capture; more CO2 means rising temperatures; hotter air means more glacial melt and so the cycle continues. The Hindu belief in samsara (the wheel of life) has many echoes, not all of them comforting.

Bowkett was not brought up on a mighty river—rather, it was in irrigation-territory in New South Wales. Much of her childhood was spent living next door to her grandparents. Her maternal grandmother was a very crafty person and taught her how to knit and sew. Bowkett liked making things and when she went to a school in Albury an art teacher there prodded her towards Caulfield Tech, where she later did ceramics in a Diploma of Design.

While there, she realised that people who didn’t have access to a kiln at the end of a course tended to abandon ceramics. So after two years she paused study, went home, built a kiln and worked for a year making pots. Returning to finish her course, she made the most of the lecturers and their skills, finished, and got a job at a pottery in Healesville mixing glazes and packing kilns. “I found that pretty exasperating, working for other people, so I went home again and started making things.” Independence rings through this woman.

Eventually, she returned to Melbourne, did a Diploma of Education and had a few teaching jobs—a career she saw as temporary because she didn’t want to get trapped. She got a space at Brunswick’s Pigtail Pottery, travelled, and in 1988 first visited India where a friend’s archaeologist contacts were working on a survey in ancient Hampi.

“I had done enough travelling to know I didn’t want to just wander around India. So it was fabulous being in Hampi. I was there for about six weeks. From there I went to Rajasthan. I was finding the further north I went, the more appealing it was becoming. India was a really exciting place and there was that sense I would come back sometime.” It was there, in Udaipur, she had the special moment seeing the pile of rotund water pots. Water is life.

The substance of earth

Outside the big windows of Bowkett’s studio, a small mountain called Pulpit Rock rises steep and boulder-encrusted. A visiting geologist told Bowkett the property is on an old part of the earth, and that the volcanic activity that hiccupped these great, once-molten lumps of stone was not recent, geologically speaking. “I don’t understand how one part of the Earth can be older than another,” she remarks. Whatever its chronology, the Earth’s clay has been in her hands, wrestled and moulded and spun and thrown to make vessels, for such a long time. It seems fitting this rocky mountain is in her view while making things.

In the potters’ colony, she was fascinated by how the locals obtain clay and turn it into objects. It comes straight off the fields in places such as Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, delivered in a big trailer drawn by a tractor and gets dropped on the road in the middle of the settlement. The streets have been recently paved so there is a hard surface for the people to work on. New drains, however, clogged up quickly. The clay is dry and visitors weave in and out of the mounds as they pass through. Jobs tend to be segregated along gender lines—women crush the clay and then wet it down over the course of the day.

After the men have finished throwing pots (a task done in the mornings), they visit the piles of wet clay amassed by the women and prepare it for throwing the next day. By this stage it is very sloppy and they add dry clay, roll it into great balls and transfer it to another pile where boys wedge it, gouging into the clay to make it more consistent in texture. “It is an incredibly fast process,” Bowkett says. “But they never get to the end of it. I have been amazed at how fantastic that clay is. Fired at a low temperature it is quite hard.” Apart from the tractor and trailer, this whole process is probably little different to when Indian pottery seems to have been established in the Indus Valley civilisation 5,000 years ago. Today there are believed to be more than a million potters in India.

Clay types are a little more diverse in Australia. In Bowkett’s two studios—one on her property, another in a garage belonging to a woman in Tallarook—at least five different types of clay can be spotted stacked against the walls. They are very refined and among about 40 that might be bought on the Australian market. In the village of Kumhaargram, by contrast, there is just the one composite clay. When Bowkett visited in 2002, she asked the potters what is the first thing they’d like to change if they could. The quality of the clay, they told her.

“When they come here to Australia, these guys are such masters of the material, it doesn’t matter what they use. For throwing on their wheels they need really soft clay so we have to cut it up, wet it down and re-wedge it. It nearly did us in last time. Poor Manori! Not that he would ever say. It was the first time I have seen him reach the extent of his energies. He is an incredibly able person. Skinny as anything. When he does come here, he fattens up a bit because he is not working as hard and eating more.”

You only have to see the potters at their wheels to understand the extent of their skills, says Bowkett. The large stone discs, big as a bicycle wheel sometimes, have a chunk of marble at the centre that balances upon another, much smaller piece of pointier hard timber. The potters deftly use a stick to quickly push the wheel into motion and then get the momentum going so it will spin and be balanced horizontally level. Because of the weight of the stone wheel, the momentum is considerable, but eventually—without more stick-prodding—it will slow and start to tilt, like some aged planet running out of puff around a star.

“They are so skilled that if it was starting to go off kilter, a potter would put his fingers somewhere on the wheel to make it go level again. It always amazes me the degree of knowledge they have about their materials.” Therein she sees some basic cultural difference: the potters have endless patience and the depth of their knowledge is born from repetition, repetition, repetition.

“Whereas I will be flitting from one thing to another, trying something different and probably don’t totally resolve everything. It’s like our diet—we don’t have the same thing day in day out. We crave difference and variety and that is the same with my work, I need to be changing things.”

That facet of cultural difference, where expectation and routine versus experimentation and unpredictability, is also marked in Bowkett’s experience of social structures. During one visit to India, Bowkett was invited to an official function in central Delhi along with some of the potters, including Manohar Lal. On meeting a dignitary, Bowkett introduced herself and then Manohar Lal, who put out his hand to the man. The dignitary ignored Manohar Lal. He would not shake the potter’s hand. This was when the true extent of the caste system was brought home to Bowkett.

“I was devastated, not that I drew attention to it,” she says. “I’m sure Manori felt he wasn’t a potter in that situation: he was someone going to Australia with me and doing these projects. I couldn’t imagine dealing with someone like that [dignitary]. I didn’t feel like Manori was being treated as an equal. It was an insult to me as well.”

On her first trip to India people had asked what she did in life and when she explained she was a potter, she was told “don’t say that, say you are a teacher”, for potters are not highly esteemed, despite the crucial service they provide. This is why she feels so comfortable at Kumhaargram: “It is very much a feeling of being at home or coming home. There is the acceptance of the community and it took a long time for it to dawn on me that it is because I am a potter. The caste system is so entrenched. Downtown Delhi you wouldn’t know. People aren’t that interested in your caste. But as soon as you leave urban areas, it can become an issue.”

The power of fire

- Banay Singh and Sandra Bowket firing the woodfired kiln

- Banay Singh chai cups drying in Tallarook

- Banay Singh and Sandra Bowket, collaborative stoneware chai cups

In the evenings, smoke hangs over Kumhaargram following the late-afternoon kiln firings. Ash flies, smoke gathers. Delhi is one of the world’s most polluted cities and regularly has much higher smog levels than notorious Beijing, the streets thick with an eerie haze. Like any urban centre in the world, the poor are pushed from one spot to the next as the tide of fashion and gentrification follows its whims and suburbia spreads outwards. At the same time, more rural folk pour into the cities in search of livelihoods.

Kumhaargram has been moved several times during its history, beginning life closer to central Delhi. Since she has been visiting its present location, Bowkett has heard many rumours of property developers wanting to commandeer Kumhaargram, and of authorities wanting to close down the kilns.

“I don’t know how they would manage to move it. The houses are beginning to become ‘pukka’ [properly built] and real estate values are increasing. You do see new industries coming into the area. Once there is critical mass of people doing something other than pottery, there will be pressure on the kilns. But as long there is a demand for the products they make, they will continue to produce them.”

On returning from her Asialink residency in India in 2012, Bowkett decided she wanted her own wood-fired kiln at home. “It has really changed everything. What I wanted to do was have a high-firing kiln that I could fire functional objects in. The idea of people having access to hand-crafted objects that are used every day, things that are not expensive, very usable, functional, stackable, is what I wanted to do. I needed the high-firing kiln because my electric kiln is reasonably small and it isn’t good at high temperatures.”

As she shows me her various kilns, I am struck by their beauty as objects in themselves. The high-firing kiln has what Bowkett describes as an “Indian chimney”, made in 2013 by some of her visitors from Kumhaargram. Long before that, in 2003, Manohar Lal and Giri Raj built her a kiln in an old tin drum. She lifts the top off. It hasn’t been used in a while, and a large redback spider hangs quietly in her web underneath. “You can fit two water pots in it. It is what Banay Singh used for firing the chai cups. We had to get mud and horse manure for the insulation. That is the design of the kilns they use at home.” There is also another gorgeous traditional kiln that fits about 30 water pots.

The first few times Bowkett fired her wood kiln with Manohar Lal and Banay Singh, it was disastrous. Since, she has had 30 about firings and now considers it very easy to fire. I peek inside to see how the air is drawn down the shelves where the pottery is carefully placed. Temperatures soar and the flame and ash and wood bring subtle colour to the clay objects.

“The ash affects the glaze as well as the clay,” Bowkett explains. “It can have different effects depending on where something is in the kiln. If you have it on that wall, it will get more colour, facing the fire.” Gradually, she has worked out the source of various effects. The clays with more iron in them go down the bottom where they take on a spotted effect, while the porcelain goes up the top. “Even though the firing is quite intense,” Bowkett says, “there is also a gentleness in the process.”

All this elemental transformation—this earth, this water and, ultimately, this fierce power of fire—seem like alchemy to me. I recall reading, as a young art student exploring psychology, how Carl Jung “rediscovered” this very old and magical precursor to modern chemistry. He saw in it the potential for great spiritual symbolism. Alchemy went on to underpin his investigations into the human unconscious: he posited we could learn to reconcile the troublesome opposites within our psyches, to make our own inner gold.

Elemental power tempered with gentleness and the forging of gold: it is all there in the creative, working relationship between Bowkett and the Kumhaargram potters. They invite us to drink deeply.

Author

A visual arts writer based in Victoria, Andrew Stephens is also an artist and the editor of Imprint, the quarterly journal published by the Print Council of Australia.

A visual arts writer based in Victoria, Andrew Stephens is also an artist and the editor of Imprint, the quarterly journal published by the Print Council of Australia.

Sandra Bowkett conducts tours of India. For details of her 2017 tour, see here.

Comments

Beautifully expressed both visually and in words. Thank you Andrew and Sandra.

I would like to read “The world in a chai cup: Sandra Bowkett and a village of Indian potters”

Thanks for your interest. You can subscribe to read this essay here – http://www.garlandmag.com/subscribe. These subscriptions help pay for a professional writer like Andrew Stephens. If money is a problem for you, feel free to make us an offer of some service.

Just an incredible woman working with some amazing poeple. Indeed she is extraordinary. Thank you Andrew for sharing this wonderful essay.

Just an incredible woman working with some amazing people. Indeed she is extraordinary. Thank you Andrew for sharing this wonderful essay.

For a less romantic take on the chai cup, read Lizzie Collingham’s fascinating “Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors”

“…in the villages these earthenware cups are often reserved for the untouchables, while the other customers are given their tea in glasses”

And we thought it was all about ecological sensitivity! Maybe it is today, but Indian culture is full of surprises.